MAVCOR Journal is an open access born-digital, double blind peer-reviewed journal dedicated to promoting conversation about material and visual cultures of religion. Published by the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion at Yale University and reviewed by members of our distinguished Editorial Board and other experts, MAVCOR Journal encourages contributors to think deeply about the objects, performances, sounds, and digital experiences that have framed and continue to frame human engagement with religion broadly understood across diverse cultures, regions, traditions, and historical periods.

A special issue guest edited by Laura S. Levitt and Oren Baruch Stier

Tending to Holocaust Objects: An Introduction

Tending to Holocaust Objects: An Introduction

This introductory essay presents the origins and aims of the special issue. It examines how objects marked by violence and loss acquire dimensions of sacrality and affect, and highlights the essential—often invisible—professional labors of care and conservation in sustaining historical memory.

We begin, appropriately, by examining a range of institutional practices in comparative perspective, considering both how Holocaust objects come to be held in archives and museums and their subsequent trajectories. These objects are initially shaped by distinct practices of donation, acquisition, and accession and their transfer between intimate, family collections and public institutions, and later through curation, custody, storage, and display. Attuned to the ways in which objects marked by violence, trauma, and dislocation resonate socially and culturally, the authors of these first three pieces ask how objects signify—how they make the past present, how they become meaningful, how their materiality resonates viscerally—and how context impacts such signification. Such contexts include donor ambivalence, the conditions of storage, shifts in custody, how objects are handled, decisions concerning care and use, spatial considerations, and more. It is important to note that these contexts are often evolving and changing: objects can become artifacts or relics, accentuated by their relationship to extremity. We can question their ontological status; we can track them on their journeys into representation, as they circulate and recirculate from one person to another, from one institution to another. Throughout these first three essays, the affective aspect of Holocaust objects emerges: these materials can evoke powerful emotional responses directed at the people who are connected to them. Thus, we see here how institutional practices matter in making the invisible visible. - OBS, LSL

In(ani)mate Objects: Between the Sacred and the Everyday

In(ani)mate Objects: Between the Sacred and the Everyday

Objects shape and legitimate human identity, especially in terms of interpersonal relations. In this article, Stone compares and contrasts how the Arolsen Archives and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum care for the objects in their possession. The varying approaches of the two institutions leads to different sorts of knowledge about the past, and has much to tell us about contemporary understandings of Holocaust museum curatorship and Holocaust memory.

Transporting the Past: Suitcases, Briefcases, and Histories of Displacement

Transporting the Past: Suitcases, Briefcases, and Histories of Displacement

Suitcases, and their smaller cousins, the briefcase, hold things. They are both object and container, possessing a range of physical properties and material connections. They are also inherently material in their demands for care and curation, creating challenges for institutions that hold them to make sense of violent and traumatic pasts.

“Disgraceful” Objects: Reacting to and Engaging with Perpetrator Materials in Archival Collections and Holocaust Museums

“Disgraceful” Objects: Reacting to and Engaging with Perpetrator Materials in Archival Collections and Holocaust Museums

An exploration of how Holocaust museums and archives confront and contextualize perpetrator materials, addressing the ethical challenges of exhibiting “disgraceful” objects, this essay examines curatorial and archival approaches to preservation, interpretation, and display, and reflects on how these materials shape public engagement, historical understanding, and moral responsibility.

In this section we pivot to those objects that are the most intimate, due to their proximity to the human body. This intimacy straddles the boundary between the living and the dead and raises questions concerning how the body is treated in a Holocaust context. How do we tend to human remains, survivor bodies, and surviving materials worn on or hidden inside the body—items that may have outlived the bodies that once bore them? How do the range of practices around death and burial accommodate the objects unearthed in the process? Does body proximity impact the sacrality of a Holocaust artifact, and what happens when an object is separated from its bearer? The essays in this section speak to ethical considerations as well, as body proximity accentuates personal, professional, and institutional concerns for the proper care and handling of these materials, raising questions about their ownership. The essays in this section engage with the forensic turn in the human sciences, contributing to our understanding of these objects as well as the events that produced them. As remnants embodying loss, these objects and even the material traces of their own prior histories can be used to reconstruct individual histories of the victims, rescuing them from oblivion and from the perpetrators’ gaze. They thus constitute elements of a counter-archive of testimonial objects that speaks against Nazi attempts to commodify the victims’ bodies and their material belongings. - OBS, LSL

Examining Body Proximity and “Sacredness” at/in Relation to Treblinka Extermination Camp

Examining Body Proximity and “Sacredness” at/in Relation to Treblinka Extermination Camp

This article presents four objects, all relating to the Treblinka death camp, that would have been worn on the bodies of Holocaust victims. Each one, however, illustrates differences in the journeys, uses, spatialities, and temporalities of proximity. These items give pause to reflect on how value and sacrality are affected when objects have been in extremely close physical contact with the (living or dead) human body, and how the context in which they are found may affect their perceived status.

The Excavated Nametag of David Juda van der Velde

The Excavated Nametag of David Juda van der Velde

What is evoked when one encounters a child’s nametag, exhumed from the soil of a former Nazi death camp? For Holocaust archaeologists, such moments collapse temporal distance, raising pressing affective and ethical questions about the persistence of the past within the material present. When such objects enter museum narratives, they bring the emotional labor and spiritual attachments of families with them, complicating the “afterlives” of things displaced by war.

Five Points of Entry: Judy Lachman's Group Photo from August 1942

Five Points of Entry: Judy Lachman's Group Photo from August 1942

Through war, ghettoization, deportations, and forced labor, Judy Lachman carried and protected from harm photographs of friends and family members, mementos of her life before and during World War II. One of these pictures depicts members of the youth Zionist organization Akiva. This article examines the photograph’s visual and material qualities, the transformations it underwent during the war, and its mediation and remediation after the war.

Our third section continues many of the themes of the previous one, in that items worn on the body also share in the body’s intimacy, especially those garments that are not visible, worn underneath other clothing. This invisibility extends to objects’ origins, in cases where the items were created covertly, and to their inaccessibility: many of the items discussed in this special issue are not on public view, and in this section we ask what that might mean for Holocaust memory and representation. How might “de-centering” the role of museum exhibitions lead to a broader consideration of the multiple functions of a museum and the different epistemes—worldviews—undergirding the objects in its care? The essays here extend the narrative potential of objects previously discussed, transcending time and space and reflecting on the ways objects themselves tell stories, both literally and metaphorically, revealing a material agency that can, at times, telegraph hopefully and poignantly into the future. In some cases, the artifacts themselves record and preserve accounts of life in the ghettos and camps, documenting experiences of labor and loss and serving as records of the transactional economies in spaces of incarceration. The objects in this section are purposive, reflecting the intentions of their creators while also assuming the qualities of the wearers. Archival records can try to capture these qualities, but we recognize that they are by nature incomplete; there is only so much we can know about these remnants, even with ongoing meticulous research. The authors of these essays ask us to consider the function of worn objects, whether decorative or ritual; readers will note several items’ individuality as well as the gender distinctions that mark particular garments historically. Here, artifacts are themselves mediators of memory, offering enticing visual records of ghetto and camp life and embodying the experiences of people before, during, and even after World War II, beyond both written narrative and oral testimony. - OBS, LSL

Objects of Witness: Holocaust Jewelry Constructed in Camps and Ghettos

Objects of Witness: Holocaust Jewelry Constructed in Camps and Ghettos

Covertly constructed from scrap or excess metal in forced labor factories and workshops, pendants, pins, bracelets, and other metal objects made in Holocaust-era ghettos and camps by prisoners were largely given as gifts to friends and family or exchanged for food or other resources. A consideration of these rare surviving objects reveals how prisoners understood the conditions they were living in and represented them in material culture, and by doing so asserted a form of material agency amid confinement and forced labor.

Wedding Dresses: Soft Landings, a Ritual Garment, and the Promises and Perils of Life After

Wedding Dresses: Soft Landings, a Ritual Garment, and the Promises and Perils of Life After

At the close of World War II, numerous Jewish brides in a Displaced Persons camp wore a remarkable parachute wedding dress now in the collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. According to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) a parachute is "something which inflates to control the descent of a falling body." Not all who wore this dress or the others like it in the UHSMM collection experienced soft landings. Wedding dresses never come with guarantees.

Inaccessible Objects: Armin Loeb’s Tallit Katan at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

Inaccessible Objects: Armin Loeb’s Tallit Katan at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

The importance of the Holocaust for Jewish and general memory has led to scholarly discussion of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in religious terms. The USHMM, like many other Holocaust memorial museums, is not, however, owned or run by a religious community and does not serve as a space of prayer. Yet visitors treat the museum space and its objects with a sense of reverence reserved for ritual spaces and relics. But what happens if such religious objects are not on display? In this article, the author turns to Armin Loeb’s tallit katan to show the value of analyzing inaccessible objects.

The authors of the essays in this section focus on ritual-textual objects. These items had specific religious functions in their original contexts, before being brushed by violence. During and after the Holocaust, these objects accumulated additional accretions of significance. The reflections here reveal the multilayered meanings of sacred objects. They also demonstrate the entangled histories of texts and things, where documentation helps in identifying and, indeed, accentuating an object’s power. Remnants of the past, the artifacts discussed in this section are both surviving and survivor objects, and their sacrality is bound to both of these roles. How do we understand the “sacred” beyond its context in “religion?” These essays address overlapping categories of sacredness, including religious, historical, personal, and associative types, and the ways objects move or are made to move between these classifications depending on ownership and accessibility, provenance and display. What happens to revered objects when they are transferred between custodians and contexts? Is the “sacred” a transferable quality? What happens if a donor does not want to part with certain items? How do the interventions of creators and curators transform an object’s sacrality? Here, objects act as anchors, sources of comfort during difficult times and orientation points afterwards. They can be embedded in networks in which ordinary and extraordinary functions and meanings overlap. These objects reflect as well the individual agency and personalities of their original owners, inheritors, and donors and often reflect those individuals’ decisions regarding their creation, care, and custody. These items are, ultimately, deeply personal reminders of individual and familial experiences. - OBS, LSL

Sacred in Function, Sacred in Memory: A Rosary and Missal from the Holocaust

Sacred in Function, Sacred in Memory: A Rosary and Missal from the Holocaust

This article examines a rosary and missal given to Beatrice "Trixie" Muchman for her confirmation while she was hiding in a small French town during the Holocaust. Although she returned to her Jewish faith following the war, she still revered the objects, keeping them long after donating the rest of her Holocaust-related materials to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum for safekeeping. The article explores the multiple layers of sacredness imbued in Muchman's rosary and missal, and considers how a federal, non-denominational institution such as the USHMM should curate and display such objects.

A Conversation with Holocaust Survivor Beatrice Muchmann

A Conversation with Holocaust Survivor Beatrice Muchmann

Susan Goldstein Snyder, formerly an acquisitions curator at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, interviews Beatrice "Trixie" Muchman, who survived the Holocaust in hiding in Belgium.

Two Layers of Text, Many Layers of Meaning: The Materiality of the Pál Szegö Diary

Two Layers of Text, Many Layers of Meaning: The Materiality of the Pál Szegö Diary

Pal Szegö’s Holocaust diary is written in the only book he had available, a Hungarian language copy of the New Testament. While the diary entries are a rich text that merits attention, examining the diary as a unique bound object that preserves traces of the diarist’s interactions with it and some of the experiences detailed in the entries foregrounds Szegö’s individuality and agency amid changing circumstances, offers insight into his complex identity as a devoted Christian convert persecuted for being Jewish, and emphasizes the significance of the diary as a survivor object.

The Missing Mezuzah

The Missing Mezuzah

The mezuzah on a wall inside the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, donated by Benjamin Meed, is the only object among the countless artifacts identified and displayed in the USHMM's Permanent Exhibition installed as if it is a useable object, i.e., without a display case and in the position of a ritually functional mezuzah. What is the place of such an object within the museum and what does it signify?

Tying a number of this special issue’s themes together, this final section features analyses of graphic objects that embody different forms of intentional communication: gratitude, instruction, desperation, desire, longing. These various, often personal, transmissions connect past with present and future and bridge wartime and postwar narratives. The range of forms of visual and textual objects discussed here constitute an appeal for materiality and its importance in telling the stories of the Holocaust. Paper, in particular. Paper is critically important for the survival and movement of both people and objects, especially in an increasingly digital age in which paper is already disappearing. Documents, both authentic and falsified, everyday and exceptional, record the spatial, temporal, and conceptual distances traveled from their origins to their final, often archival, resting places, serving as symbolic grave markers. They register multiple border crossings, both national and artistic, asking whether such boundaries are sites of constraint or negotiation, and what role bureaucracy plays in regulating identity. Yet, the contingency of the materials often used and the chance survival of the artifacts themselves point to these items’ precarity. At the same time, even tiny, nearly insignificant objects serve as powerful witnesses to an ever-distant past. The survival of such objects and their preservation testify to their resilience. These final essays have a tactile presence and an affective allure. They speak to the intimate experiences of exile and displacement for people as well as things. They show us how we may orient ourselves and navigate memory in time and space as they guide future generations in their journeys into the past. - OBS, LSL

“The book is small so it can be hidden”: Leia Kreimer’s Tiny Book from the Vapniarka Concentration Camp

“The book is small so it can be hidden”: Leia Kreimer’s Tiny Book from the Vapniarka Concentration Camp

During the Holocaust, even within the extreme conditions of life in concentration camps, people chose to keep and—in some cases—create objects that do not appear to fulfill essential human needs. Leia Kreimer’s tiny book, made for her as a gift, is one example. Its production, exchange, and ultimate survival illuminate the enduring resilience of the book as a cultural form that is both text and object.

From the Umschlagplatz to The Wiener Holocaust Library: Maria and Maximillian Wortman’s Last Letters

From the Umschlagplatz to The Wiener Holocaust Library: Maria and Maximillian Wortman’s Last Letters

In September 1942, in the Warsaw ghetto in German-occupied Poland, Maria and Maximilian Wortman hastily wrote a letter to their daughter, Dziunia, from whom they had become separated. The couple had been selected for deportation to the death camp Treblinka, and they were gathered on the Umschlagplatz, the railway siding from where the deportation trains departed. Their final words to their daughter are written on the reverse of a scrap of paper no larger than 11 x 15 cm.

Hedda Sterne’s Photomontages: Passport to Life

Hedda Sterne’s Photomontages: Passport to Life

This essay examines Hedda Sterne's 1941 Romanian passport and her little-known photomontages from Life magazine as parallel "documents of exile." The passport traces her perilous flight from Europe, serving as an unintended autobiography of survival. Her photomontages, composed from magazine clippings, became visual testimonies that confront the dissonance between American popular culture and her feelings of anxiety as a refugee. This study uses a conservation and art history lens to explore how paper, in both bureaucratic and artistic forms, mediated Sterne's identity and experience of displacement.

Maps as Artifacts of Remembrance: The Sefer Kostopol

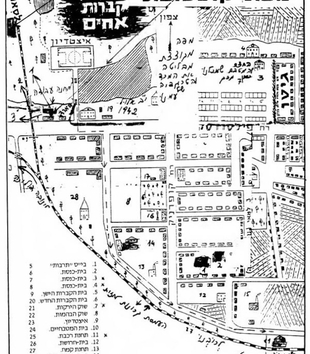

Maps as Artifacts of Remembrance: The Sefer Kostopol

Yizkher bukher, collaboratively authored memorial books devoted to single cities, can offer descendants of Holocaust survivors access to the places their ancestors were forced to flee. Jennifer Rich reflects on her encounter with Sefer Kostopol, the book written about her grandmother's hometown of Kostopol, Ukraine, and specifically the way maps in this and other yizkher bikher can help envision spaces now lost and destroyed.

On the Multiple Lives of Bannerstones: Indigenous North America 6,000 BCE to the Present

On the Multiple Lives of Bannerstones: Indigenous North America 6,000 BCE to the Present

Looking at Indigenous bannerstones from what is known as North America, their unique shapes and symmetrically drilled holes carved from an array of lithics, from sedimentary stone to quartz, I wonder what stories they are telling. Do their stories begin with the sculptors who made them east of the Mississippi Valley in 6,000 BCE or do they begin four billion years ago when volcanic heat from the earth’s core melted and congealed minerals to form the oldest terrestrial rocks?

Beijing's Tibetan Buddhist temples have always been places through which diverse groups of people moved. During the Qing, these were spaces where elites from different backgrounds met, collaborated, and enacted the multicultural character of the empire within the capital. The temples themselves announced the pluralistic nature of the Qing dynasty, as well as its grandeur, through their public display of signs and stelae aimed at the multi-ethnic audiences of the empire.

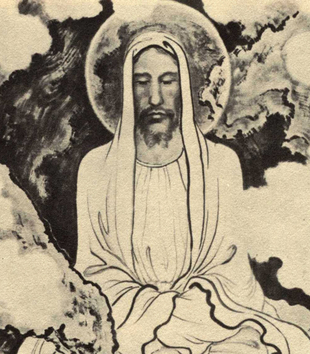

In Search of Multiple Colors of Christ: Daniel J. Fleming and the American Protestant Encounter with Asian Christian Visual Arts, 1937-1940

In Search of Multiple Colors of Christ: Daniel J. Fleming and the American Protestant Encounter with Asian Christian Visual Arts, 1937-1940

Fleming’s trilogy illustrates the complex dynamics of race, religion, and visual arts in the interwar United States. Though the extant scholarship highlights the increasing Anglo-Saxonization of Jesus’s body in American visual culture in this era, Fleming’s story reveals a virtually opposite impulse in liberal Protestantism: to search for multiple colors of Christ.

Like a Virgin? Breaking, (un)making, and replicating the Madonna across time, space, and toy stores

Like a Virgin? Breaking, (un)making, and replicating the Madonna across time, space, and toy stores

The authors set the nucleating body of the medieval Virgin in conversation with contemporary reimaginings of the Madonna to ask how hybridization, fracture, insertion, assemblage, color, multiplicity, and meaning around sacred and secular exchange can change the way we know and see in relation to these forms from the medieval to the postmodern.

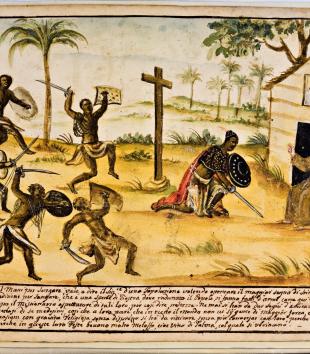

Resoundings of Early Modern Afro-Catholic Festive Culture

Resoundings of Early Modern Afro-Catholic Festive Culture

This Constellation is intended to complement the author's book and give readers access to color versions of some of its illustrations, which could only be printed in black and white in the original publication. As in other parts of the Iberian world (i.e., the Iberian Peninsula and all the territories under Spanish and Portuguese control), these performances were usually staged by lay Catholic confraternities.

Petitionary Devotion: Folk Saints and Miraculous Images in Spanish America

Petitionary Devotion: Folk Saints and Miraculous Images in Spanish America

Votive practice in the Americas has Indigenous, Christian, and syncretic origins that contribute to the diversity of offerings, as do social class, gender, age, and region. Petitionary devotion is structured by an exchange that the votary proposes to a folk saint or miraculous image. The offerings that votaries promise are based on the presumption that folk saints and miraculous images, because they are like us, value what we value.

A special issue curated by Kati Curts and Alex Kaloyanides

Characterizing Material Economies of Religion in the Americas: An Introduction

Characterizing Material Economies of Religion in the Americas: An Introduction

Kati Curts and Alex Kaloyanides introduce this special issue of MAVCOR Journal devoted to examining four key categories: “Material,” “Economies,” “Religion,” and “America(s).” The ambition of this issue is that the collective inquiries of its authors, which span various interpretive histories and genealogical fragments, can offer ways to better understand their assorted conveyances, as well as the powerful grip of their critical conjunction.

Medals, Memory, and Findspots

Medals, Memory, and Findspots

For many Indigenous people of Turtle Island, also known as North America, treaty medals are material reminders of sacred promises made between their nations and the British Crown or the U.S. Government. Settlers and colonial officials, by contrast, have often treated these medals as mere trinkets.

Julia Greeley, Denver’s Angel of Charity

Julia Greeley, Denver’s Angel of Charity

More than a portrait of a holy person, an icon structures a present encounter with a saint and the community that the saint represents. What kind of encounter does Greeley’s icon conjure with race and Catholicism in the Old West?

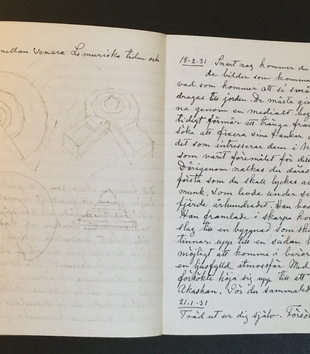

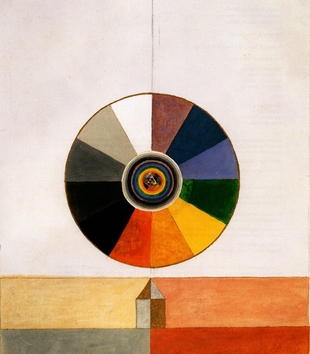

Hilma af Klint's Temple for the Paintings

Hilma af Klint's Temple for the Paintings

Through Af Klint’s journal entries and sketches, we can shift analyses of sacred space from the guise of transcendent force that simply “appears,” in the phenomenological nomenclature, and instead approach it as technique.

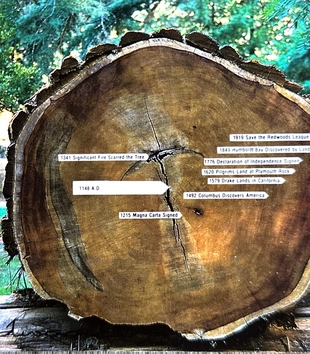

Tree Rings and Blood Lines

Tree Rings and Blood Lines

These redwood rings are both family trees and family circles, literally naturalizing a canonical “American” familial heritage insistently recited and instantiated in many media and locations: artistic and built environments, judicial practice, legislation and policy, textbooks, land use, and national land theory. Heritage is a family business.

Corporealizing Moroccan Place

Corporealizing Moroccan Place

I wondered—how does a person become a place? A street, city quarter, mosque, or town could take the name of the wali interred there, like the cities of Sidi Slimane and Mawlay Idris. The sacred enters physical space through the body.

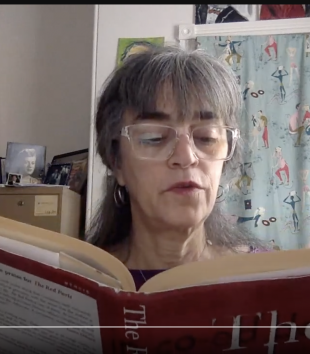

A Photograph in Words

A Photograph in Words

In her memoir, The Red Parts, Maggie Nelson writes about the over-thirty-year-old unsolved murder of her aunt, Jane Mixer, a case brought back to life in a Michigan court room. Who gets to tell this story? How should it be told?

Pausing on a Sunday: What Kind of Secular is the American Musical?

Pausing on a Sunday: What Kind of Secular is the American Musical?

The musical in which this song appears includes archetypal depictions of the modern artist and his attendant gendered capacities and failures. Sondheim would point out: its lyric is a single sentence; it is a description of a process; it includes a word, “forever,” that he observes makes him cry.

Material Economies of Life-Time: Grief, Injury, Expiation, Desire

Material Economies of Life-Time: Grief, Injury, Expiation, Desire

Tracy Fessenden, Hillary Kaell, and Alexia Williams discuss three iterations of religious, material economies: bus stop clocks, cloistered Magdalens, and a Catholic prayer card from Denver.

The Intimate Ironies of the Wifey: Material Religion and the Body

The Intimate Ironies of the Wifey: Material Religion and the Body

From the familiarity of scent to the spread of colonial/space time, and through Black vernacular culture and “linking” us to divine power through the digital, Ellen Amster, Dusty Gavin, and Suzanne van Geuns introduce us to the strange intimacies of the wifey.

Designing Risk, Accumulating Failure: Purgatory, the Planned, and Primitive Accumulation

Designing Risk, Accumulating Failure: Purgatory, the Planned, and Primitive Accumulation

In Fall 2020, Paul Johnson, Emily Floyd, and Kati Curts met on Zoom. In this edit of their extended conversation, the authors question “planned sacred space,” the role of design in creating religious experience, and the category of the “relic.”

A Closing Conversation

A Closing Conversation

If the Marxian dialectic culminates with the mystification of the commodity, these essays seem to envision a sacralization and re-sacralization of the profane, such that matter is the accumulation of sacred value. Transcendence and enchantment in this account are very much “real” and just as ontologically entrenched as capitalism.