MAVCOR Journal is an open access born-digital, double blind peer-reviewed journal dedicated to promoting conversation about material and visual cultures of religion. Published by the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion at Yale University and reviewed by members of our distinguished Editorial Board and other experts, MAVCOR Journal encourages contributors to think deeply about the objects, performances, sounds, and digital experiences that have framed and continue to frame human engagement with religion broadly understood across diverse cultures, regions, traditions, and historical periods.

MAVCOR began publishing Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion in 2014. In 2017 we selected a new name, MAVCOR Journal. Articles published prior to 2017 are considered part of Conversations and are listed as such under Volumes in the MAVCOR Journal menu.

Tears of the Sun: The Naturalistic and Anthropomorphic in Inca Metalwork

Tears of the Sun: The Naturalistic and Anthropomorphic in Inca Metalwork

Why did the Inca approach metal so differently from other sculptural media, most notably stone?

Making Crosses, Crossing Borders: The Performance of Mourning, the Power of Ghosts, and the Politics of Countermemory in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands

Making Crosses, Crossing Borders: The Performance of Mourning, the Power of Ghosts, and the Politics of Countermemory in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands

If the land “was Mexican once and Indian always,” migrants are not outsiders or “illegals.” They—we—belong to the land.

Interview with American Sufi Artist Michael Green

Interview with American Sufi Artist Michael Green

A follower of Bawa Muhaiyaddeen, Green is based in Pennsylvania and is best known for his illustrations in The Illuminated Rumi (1997).

Virtual Meditation Cushion (Zafu)

Virtual Meditation Cushion (Zafu)

What does a virtual meditation cushion tell us about material and visual cultures of religion?

Julian Voss-Andreae, Angel of the West

Julian Voss-Andreae, Angel of the West

The power to protect against “nature” now dwells in the human scientific-technological skills mastered by a certain culture, whose prowess enables it to discover these new (meta)physical angels and harness their powers.

Material Establishment and Public Display

Material Establishment and Public Display

The cultural politics of space has to do not simply with space itself, but with how it is occupied, enacted, performed, and marked—and sometimes, in Hawaiʻi and elsewhere, at least apparently unmarked.

Ex-Votos, Shrine of St. Roch, New Orleans

Ex-Votos, Shrine of St. Roch, New Orleans

Ex-votos at the Shrine of St. Roch occupy a complex place within conceptions of New Orleans as the subject of Protestant fascination with exoticized material aspects of Catholic practice.

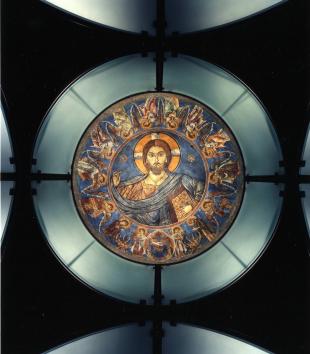

Printing the Body of Christ on Fabric

Printing the Body of Christ on Fabric

While most Renaissance and Baroque engravings, etchings, and woodcuts were printed on paper, some extraordinary impressions were produced on silk or linen. Contact relics provided a devotional inspiration for the most evocative of these prints on fabric.

Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt

Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt

The carte-de-visite of Maximilian von Habsburg’s shirt satisfied a sensational interest in the political event and served as a mourning object, offering the living both visual and tactile connections to the deceased to aid in the grieving process.

Fabric of Devotion: William Quiller Orchardson’s The Story of a Life and Women Religious in Victorian Britain

Fabric of Devotion: William Quiller Orchardson’s The Story of a Life and Women Religious in Victorian Britain

Produced in a Christian tradition for the viewing pleasure of the London art world's cultured audiences, William Quiller Orchardson’s The Story of a Life alludes to the controversies and contentions of religious life and women’s roles in mid-nineteenth-century Britain.

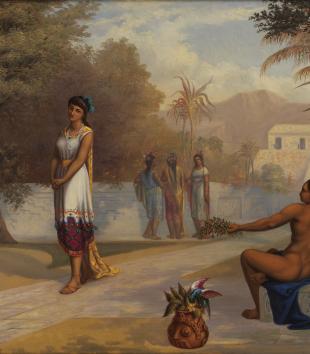

George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden

George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden

Utah artist George Martin Ottinger painted Aztec Maiden during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when numerous theories proliferated about the history and origins of indigenous American civilizations.

Revisiting the Property Room: A Humanist Perspective on Doing Justice and Telling Stories

Revisiting the Property Room: A Humanist Perspective on Doing Justice and Telling Stories

What does it mean to hold onto evidentiary objects, ordinary objects that may never make it to court, the evidence from the vast majority of crimes that remain otherwise unresolved, including so many of the horrific crimes that constitute the Holocaust?

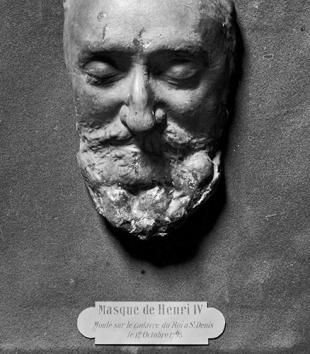

The Revolutionary Exhumations at St-Denis, 1793

The Revolutionary Exhumations at St-Denis, 1793

The French Republic's July 1793 exhumation of the royal tombs intertwines not only contemporary religion and politics but also religious traditions with contemporary intellectual debate.

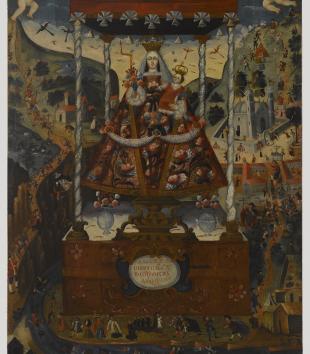

Our Lady of Cocharcas

Our Lady of Cocharcas

Material objects, including a group of documentary paintings of Our Lady of Cocharcas, recall the processes by which ancient Andean pilgrimage traditions became deeply integrated into late-colonial socio-religious consciousness.

Mask with Superstructure Representing a Beautiful Mother (D'mba)

Mask with Superstructure Representing a Beautiful Mother (D'mba)

What is the meaning of the word "spirit" in Africa?

The Politics of (Mere) Presence: The Islamic Center of Murfreesboro, Tennessee

The Politics of (Mere) Presence: The Islamic Center of Murfreesboro, Tennessee

The old Islamic Center of Murfreesboro was not, it seems, meant to be seen at all. A yearning to blend in, be ordinary, unremarkable, even overlooked, would, as I later discovered, inflect the architectural presentiments of the old and new centers alike, and provide an apt metaphor for the struggles that have confronted the Islamic community in this small city in central Tennessee.

Praying through the senses: The Prayer Rug/Carpet and the Converging Territories of the Material and the Spiritual

Praying through the senses: The Prayer Rug/Carpet and the Converging Territories of the Material and the Spiritual

Consumption as a material practice changes religious meanings and practices, and value comes to be invested in certain religious objects, rituals, and ideas rather than others.

Imam Shamsi Ali: Thoughts on Islam and Material Culture

Imam Shamsi Ali: Thoughts on Islam and Material Culture

Imam Shamsi Ali is an Islamic scholar, Chairman of the Al-Hikmah Mosque in Astoria, and the Director of Jamaica Muslim Center in Queens.

Reverend Alex Dyer: Tradition and Innovation in the Episcopal Church

Reverend Alex Dyer: Tradition and Innovation in the Episcopal Church

Ashley Makar interviewed Reverend Alex Dyer, priest-in-charge of St. Paul and St. James Episcopal Church of New Haven, CT in May 2011.

Martin Puryear, Desire

Martin Puryear, Desire

The world of handmade objects and manual labor turns strange in Puryear's Desire, and in this way, the ordinary becomes—here is list of options, choose one—estranged, uncanny, defamiliarized.

William Vander Weyde, Leon F. Czolgosz, McKinley Assassin

William Vander Weyde, Leon F. Czolgosz, McKinley Assassin

Early debates around the use of the electric chair pivoted on the convergence of state and divine power.

The Balvanera Escudo

The Balvanera Escudo

Nun's badges worn in colonial New Spain not only articulated a woman’s religious affiliations, family fortune, and ethnic purity but also expressed her desire to influence political opinion.

Adonai/Adidas T-Shirt

Adonai/Adidas T-Shirt

The t-shirt’s appropriation of a multinational sportswear corporation’s logo into a sacred Hebrew name for God could be simply a clever play on words, but a more critical approach might take into account the commodification of this sacred name for the deity and its subsequent selling in the marketplace for profit.

Julie Dickerson: Creative Currents

Julie Dickerson: Creative Currents

Ashley Makar interviewed Julie Dickerson in 2010 while she was painting a mural of “dancing saints”—ranging from Moses’ sister Miriam to Martin Luther King—in the undercroft at St. James and St. Paul Episcopal Church in New Haven, Connecticut (affectionately nicknamed “St. PJ's”).

C. C. A. Christensen, Joseph Preaching to the Indians

C. C. A. Christensen, Joseph Preaching to the Indians

Although LDS doctrine esteemed Native Americans as literal descendants of the peoples of the Book of Mormon, relations between Mormons and Indians in Utah grew increasingly strained as resources became scarce. Christensen’s work reflects this divided perspective.

Portable Altar of Countess Gertrude

Portable Altar of Countess Gertrude

The portable altar seems to have developed in the missionary world of the seventh century, to meet the Church's requirement that Mass be celebrated only on a consecrated altar—a requirement that strengthened the position of bishops, who alone could consecrate them.

Thomas Eakins, The Crucifixion

Thomas Eakins, The Crucifixion

In his 1880 The Crucifixion, Thomas Eakins, a reputed agnostic, crafted a realist interpretation of one of the central devotional subjects in Christian art, challenging the traditional iconography of the crucifixion by eliminating all signs of divine presence.

Gordon Parks, Dresser in the bedroom of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman

Gordon Parks, Dresser in the bedroom of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman

Visibly claiming to regulate the prescribed Christian imitation of the biblical figures they represented, late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century statues of light-complexioned religious figures populated domestic spaces, churches, and missions fields, and implied that looking like Jesus or Mary or John might be more “natural” or “complete” for some than for others.

Art That Breathes: Lewis deSoto’s Paranirvana (self-portrait)

Art That Breathes: Lewis deSoto’s Paranirvana (self-portrait)

Unlike its solid stone predecessor, deSoto’s work, made from painted polyethylene cloth, is hollow, filled only by air from a fan that keeps the sculpture inflated. The resemblance to the reclining Buddha is nonetheless remarkable, from the curls of hair to the folds of the robe, the one exception being that deSoto superimposed his own facial features, complete with goatee, on this Buddha.

Chalkware, Plaster, Plaster of Paris

Chalkware, Plaster, Plaster of Paris

In the second half of the nineteenth century, in Europe and the United States, chalkware accomplished for three-dimensional devotional objects what chromolithography managed for images in two dimensions.

James Latimer Allen, Madonna and Child

James Latimer Allen, Madonna and Child

During the Harlem Renaissance, mother and child portraits and figure studies were especially popular in the African American media, signaling the importance placed on motherhood and the nurturing of future generations.

Aparajita Guha: Conversation about Contemporary Hindu Spiritual Practice

Aparajita Guha: Conversation about Contemporary Hindu Spiritual Practice

This conversation about spirituality happened in the home of Aparajita Guha in Rexford, New York, on June 20, 2012. Guha, a practicing Hindu, is a family friend of Ashley Makar, who is a practicing Christian.

Viaticum, Last Rites Cabinet, Sick Call Set

Viaticum, Last Rites Cabinet, Sick Call Set

Among the material items that might occupy the pre-Vatican II American Catholic home, regardless for the most part of the occupant’s ethnicity or familial nation of origin, the last rites cabinet or viaticum (Latin for “supply of provisions for a journey”) asserted a powerful daily and nightly presence.

Mark Rothko, No. 5/No. 22

Mark Rothko, No. 5/No. 22

Strong, gestural markings in the central red band distinguish this painting from Rothko’s other mature works. This anomaly consists of long, gently undulating lines formed by gouging the surface of the paint all the way to the canvas before it dried. Straining out from a central point, the horizontal lines contrast sharply with the fuzzy, indeterminate edges of the other elements of the painting.

Ford Madox Brown, Work

Ford Madox Brown, Work

Ford Madox Brown’s allegory of labor in all its forms is the most ambitious Pre-Raphaelite painting of modern life and a profound meditation on the relationship between art, religion, and labor in Victorian society.