For many Indigenous people of Turtle Island, also known as North America, treaty medals are material reminders of sacred promises made between their nations and the British Crown or the U.S. Government. Settlers and colonial officials, by contrast, have often treated these medals as mere trinkets. Often made of durable and polishable silver, treaty medals were gifts given by representatives of the Crown or the U.S. Government to Indigenous peoples in honor of the promises made between them to share the land. Frequently given to mark the anniversaries of the nation-to-nation treaties that made possible the entities of Canada and the United States, the medals, with images of handshakes, the shining sun, and flowing rivers, are also reminders that all parties to treaty agreements worked in reference to earthly and spiritual jurisdictions.1 Where Indigenous leaders referenced the Creator in treaty negotiations, representatives of the Crown, in the Canadian case, called upon the Christian-derived authority of the monarch. In some cases, Indigenous leaders were known to reject medals made of inferior metal as unsuitably durable markers of the treaty as a sacred promise.

The “findspots” of treaty medals—Indigenous homes, museum vitrines, gift shops, private collections, online videos and collections—give them varying meanings as emblems of material economies of religion in Turtle Island. Archaeologists use the concept of the findspot to reflect on what they can learn about a material artifact if they know where it was found. But findspots are also a helpful concept for anyone who wants to reflect on the significance of the place and time that they encounter a material artifact. Thinking about where I, as a white, Canadian woman, encountered treaty medals helped me to see in new ways the relationships among metal, memory, and treaty responsibilities.

The research of Alan Ojiig Corbiere, history professor and Anishinaabe knowledge holder, is the first place where I encountered treaty medals. Prof. Corbiere has given countless talks on how treaty medals, and other material artifacts, act as complex reminders of the treaties agreed to between Indigenous Nations and colonial representatives. Listening to him and reading his work prepared me for paying attention to treaty medals.2

- 1Pamela E. Klassen, “Spiritual Jurisdictions: Treaty People and the Queen of Canada,” in Ekklesia: Three Inquiries in Church and State, eds. Paul Christopher Johnson, Pamela E. Klassen, and Winnifred Fallers Sullivan (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 107-174.

- 2Alan Ojiig Corbiere, “Anishinaabe Treaty-Making in the 18th- and 19th-Century Northern Great Lakes: From Shared Meanings to Epistemological Chasms,” PhD diss., (York University, Toronto, 2019).

I encountered the first treaty medal pictured here (Fig. 1) at the “We Are All Treaty People” exhibit at the Manitoba Museum in Winnipeg, Treaty 1 Territory. Curator Maureen Matthews explained to me that in designing the exhibit she consulted with Anishinaabe Elders, who advised that when visitors encountered the treaty medals they should also encounter the sacred pipes that were smoked at treaty negotiations. But in order to display the sacred pipes held in the collections, the Elders counseled, the museum needed to ensure the pipes were appropriately feasted in the community. This meant taking the pipes out of the museum so they could be honored, touched, and smoked. As a visitor to the museum, when I found these treaty medals displayed in relation to sacred pipes I learned that treaty medals were not enough on their own to provoke memory and maintain the responsibilities of treaty people.

The second medal I’ve shared here (Fig. 2) is one that I encountered in the summer of 2019 at the gift shop of the Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung Historical Centre, the site of the Manitou Mounds along the banks of Manidoo Ziibi (Rainy River), and run by Rainy River First Nations. I had been visiting Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung since 2012, but I had not noticed the medal at the gift shop before. I bought the medal, which came in velvety case accompanied with a piece of paper that explained that it was commissioned in 1997 by the Rainy River First Nations to commemorate medals given at Treaty 3 (1873) and later in 1920. When I asked my friend and colleague Art Hunter, a knowledge holder who works at Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, he speculated that it may also have been made to mark a 1997 Elders’ Gathering held at Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung. At that gathering, the Elders wrote and ratified Manito Aki Inakonigaawin, or the Great Earth Law, and “brought the written law through ceremony.” Encountering this medal at the gift shop and talking with Art prompted me to learn about ongoing efforts by Grand Council Treaty #3 Anishinaabe Nation to re-activate Anishinaabe law as a way “to respect and protect lands” that may be at risk due to “over-usage, degradation and un-ethical processes.”

In fall 2022, Art Hunter and I convened another gathering at Kay-Nah-Chi-Wah-Nung, together with our colleague Krista Barclay, which brought together Indigenous Elders, regional museum curators, and university researchers at the Manitou Mounds. We were honoured that Ogichidaa (Grand Chief) Francis Kavanaugh of Grand Council Treaty #3 joined the gathering, and shared his understanding of Manito Aki Inakonigaawin. One of the leaders who wrote the Great Earth Law and brought it through ceremony, Ogichidaa Kavanaugh emphasized once again the sacred nature of treaty promises.

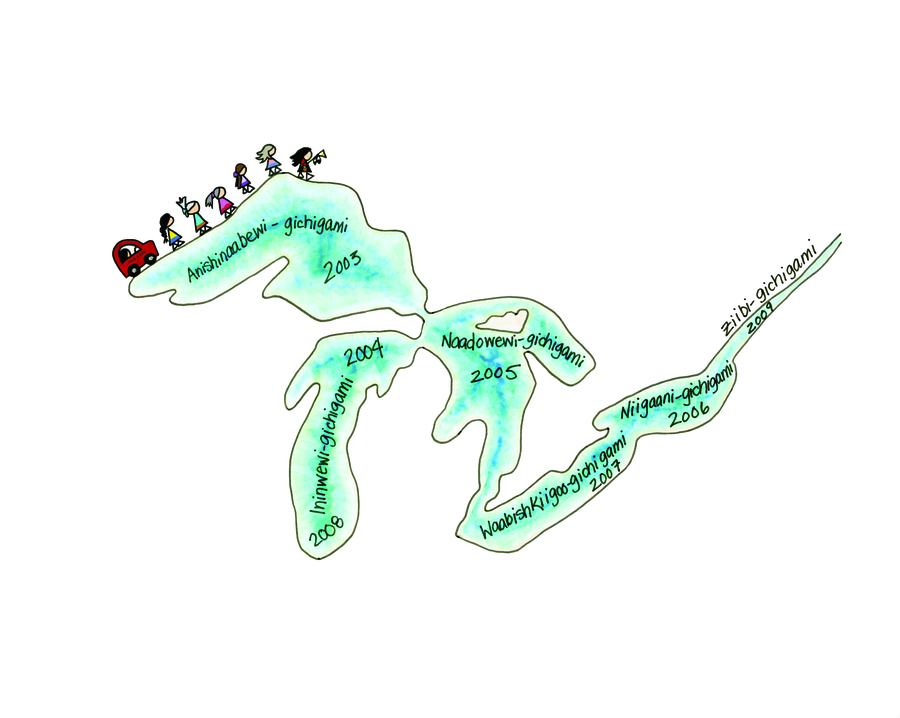

One final image I share here (Fig. 3) pictures the efforts of an Anishinaabe Nokomis (grandmother) named Josephine Mandamin, also known as “the Water Walker,” to respect and protect the lands and waters of the Anishinaabeg. The drawing is courtesy of artist/author Joanne Robertson, who wrote and illustrated a children’s book to tell the story of Nokomis Mandamin’s Great Lakes water protection walks.3 Mandamin was moved to action by an Anishinaabe Elder who prophesied that water would soon come to be as costly as gold due to environmental degradation. She began in 2003 by walking around Anishinaabewi-gichigami or Lake Superior. Before embarking, Mandamin sought advice from Elders at Rainy River First Nations, including Al Hunter, Art’s brother, who had completed an earlier water walk. I learned about the connection between Josephine Mandamin and Al Hunter through reading her 2011 article “N’guh izhi chigaye, nibi onji: I will do it for the water,” co-written with Deborah McGregor and Hillary McGregor, and published in Anishinaabewin Niizh.4

Putting together Josephine Mandamin’s story with Joanne Robertson’s beautiful image, and combining this with what I had learned about the ongoing lives of treaty medals, helped me to see new connections and responsibilities in my life and work. I live beside Niigani-gichigami, or Lake Ontario, which eventually connects with Anishinaabewi-gichigami, which eventually flows into Manidoo Ziibi and beyond. Finding treaty medals, as well as thinking and talking about them with others, has helped me to better understand that everyone who lives on these lands and waters must learn about treaties and remember our responsibilities. Thinking about the material economies of religion in these territories calls us to think in languages other than English, however haltingly, and by way of laws not rooted in the Christian-infused Crown, such as Manito Aki Inakonigaawin.

- 3Joanne Robertson, The Water Walker, Ojibwe translation by Shirley Williams and Isadore Toulouse (Toronto: Second Story Press), 2017.

- 4Josephine Mandamin, Deborah McGregor, and Hillary McGregor, “N’guh izhi chigaye, nibi onji: I will do it for the water,” in Anishinaabewin Niizh: Culture Movement, Critical Moments, eds. Alan O. Corbiere, Deborah McGregor, and Crystal Migwans (M’Chigeeng First Nation: Ojibwe Cultural Foundation, 2011), 12-23.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2022.9

1. Pamela E. Klassen, "Medals, Memory, and Findspots," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.9.

Klassen, Pamela E. "Medals, Memory, and Findspots." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.9.