Miguel A. Valerio is an interdisciplinary cultural scholar of the African diaspora in the Iberian world. Besides Sovereign Joy, he is the author of numerous articles on the Black experience in colonial Latin America.

Bernardino d'Asti, Missione in Prattica

Bernardino d'Asti, Missione in Prattica

Afro-Brazilian Kings and Queens in Riscos iluminados de figurinhos de negros e brancos dos Uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro Frio

Afro-Brazilian Kings and Queens in Riscos iluminados de figurinhos de negros e brancos dos Uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro Frio

Afro-Peruvian Musical Traditions in Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón, Trujillo del Perú

Afro-Peruvian Musical Traditions in Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón, Trujillo del Perú

Black “Cacique” on Elephant, for Le Grand Bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut

Black “Cacique” on Elephant, for Le Grand Bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut

Africa

Africa

In my book, Sovereign Joy: Afro-Mexican Kings and Queens, 1539-1640, I study the performance of festive Black kings and queens in Mexico City’s first hundred years of Spanish colonization.1 This Constellation is intended to complement the book and give readers access to color versions of some of its illustrations, which could only be printed in black and white in the original publication. As in other parts of the Iberian world (i.e., the Iberian Peninsula and all the territories under Spanish and Portuguese control), these performances were usually staged by lay Catholic confraternities. The Mexican examples I analyze form the earliest textual evidence for this practice, which has been documented throughout the African diaspora.2 The book begins with the earliest textual example we have of this tradition, which describes a performance that took place in Mexico City in 1539 within a broader two-day festival to commemorate the Truce of Nice (1538). After describing a mock hunt staged by Indigenous performers, the conquistador turned chronicler, Bernal Díaz del Castillo (c. 1492-1584), who witnessed the festivities and wrote some fifty years after the fact, tell us that the mock hunt

was nothing compared to the performance of horseback riders made up of Black men and women [negros y negras] who were there with their king and queen, and all on horses, they were more than fifty, wearing great riches of gold and precious stones and pearls and silver; and then they went against the savages and they had another hunt, and it was something to be seen the diversity of their faces, of the masks they were wearing, and how the Black women breastfed their little children and how they paid homage to the queen.3

This brief passage speaks to the universe of Black festive practices that was already unfolding in the Iberian world. Lay confraternities, as the institutions that allowed Afrodescendants to form community, build safety nets, and pool resources, played a central role in this festive culture.4

- 1Miguel A. Valerio, Sovereign Joy: Afro-Mexican Kings and Queens, 1539-1640 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

- 2See, for example, Judith Bettelheim, “Carnaval of Los Congos of Portobelo, Panama: Feathered Men and Queens,” in African Diasporas in the New and Old Worlds: Consciousness and Imagination, edited by Geneviève Fabre (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2006), 187-209; Renée Alexander Craft, When the Devil Knocks: The Congo Tradition and the Politics of Blackness in Twentieth-Century Panama(Columbus: The Ohio State University Press, 2015); Marina Mello e Souza, Reis negros no Brasil escravista: história da festa de coroação de rei congo (Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG, 2002); Elizabeth W. Kiddy, Blacks of the Rosary: Memory and History in Minas Gerais, Brazil (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2005); Cécile Fromont, “Dancing for the King of Congo from Early Modern Central Africa to Slavery-Era Brazil,” Colonial Latin American Review 22:2 (2013), 184-208; Patricia Fogelman and Marta Goldberg, “‘El rey de los congos’: The Clandestine Coronation of Pedro Duarte in Buenos Aires, 1787,” in Afro-Latino Voices: Narratives from the Early Modern Ibero-Atlantic World, 1550-1812, edited by Kathryn Joy McKnight and Leo J. Garofalo (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2009), 155-173; Alex Borucki, From Shipmates to Soldiers: Emerging Black Identities in the Río de la Plata (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2015), 99-105; , Patricia Lund Drolet, El ritual congo del noroeste de Panamá: una estructura afro-americana expresiva de adaptación cultural (Panama City: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 1987); Jeroen Dewulf, From the Kingdom of Kongo to Congo Square: Kongo Dances and the Origins of the Mardi Gras Indians (Lafayette: University of Louisiana at Lafayette Press, 2017); Philip A. Howard, Changing History: Afro-Cuban Cabildos and Societies of Color in the Nineteenth Century (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1998); William D. Piersen, Black Yankees: The Development of an Afro-American Subculture in Eighteenth-Century New England (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988), 117-128; Tamara J. Walker, “The Queen of Los Congos: Slavery, Gender, and Confraternity Life in Late-Colonial Lima, Peru,” Journal of Family History 40, no. 3 (2015): 305-322. I have found an example of this performance in Macau in 1644, for the city’s festivities for the proclamation of John IV of Portugal: João Marques Moreira, Relação da Magestosa, Misteriosa, e Notavel Acclamaçam, que se fez a Magestade d’El Rey Dom IOAM O IV. nosso Senhor na Cidade de nome de Deos do grande Imperio da China, & festas que se fizerão pellos Senhores do Governo publico, & outras pessoas particulares (Lisbon: Domingos Lopes Rosa, 1644), 32.

- 3Bernal Díaz del Castillo, Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (manuscrito “Guatemala”), ed. José Antonio Barbón Rodríguez (ca. 1575, first edition: Mexico City: Colegio de México/UNAM 2005), 755. Unless otherwise noted, all translations are mine.

- 4See, for example, Valerio, Sovereign Joy; Kiddy, Blacks of the Rosary; Cécile Fromont, ed., Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of Atlantic Tradition (State Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019); Lisa Voigt, Spectacular Wealth: The Festivals of Colonial South American Mining Towns (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2016), 121-150.

Díaz del Castillo’s description marks Mexico City as an early site of this Afro-diasporic tradition and, furthermore, given his reference to Black women breastfeeding their little children, of Black kinship. The Afro-diasporic confraternal kinship Díaz del Castillo evokes, like the performers themselves, first formed in the Iberian Peninsula and passed through the Caribbean on its way to Mexico and elsewhere in the Americas.On the Iberian beginnings of Black confraternities, see Debra Blumenthal, “La Casa dels Negres: Black African Solidarity in Late Medieval Valencia,” in Black Africans in Renaissance Europe, ed. T. F. Earle and K. J. P. Lowe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 225-246; Erin K Rowe, Black Saints in Early Modern Global Catholicism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 46-86; Carmen Fracchia, “Black but Human”: Slavery and the Visual Arts in Hapsburg Spain, 1480-1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2019), 48-55; Jeroen Dewulf, Afro-Atlantic Catholics: America’s First Black Christians (South Bend: University of Notre Dame Press, 2022), 13-34. Nonetheless, Díaz del Castillo’s otherwise hermetic passage needed unpacking. In my book, the paucity of Mexican sources (six) meant that the best way to do this was by adapting a diasporic framework, which I used to compare texts and visual culture about this Afro-diasporic tradition from different localities of the Iberian world across the early modern period (1492-1800). Comparing the atomized, sporadic, and disjointed set of sources available about the Afro-diasporic experience across the centuries and different Iberian localities allowed me to bring to the fore continuities across Afrodescendant networks.

A 1762 Brazilian text, the Luso-Brazilian Francisco Calmon’s Relação das fautíssimas festas (Account of the Most August Festival), proved particularly useful for unlocking Díaz del Castillo’s brief reference. Calmon’s text, while describing a performance that included an element not found in the Mexican examples—an embassy that announced the performance of the king and queen—bore many similarities with Díaz del Castillo’s text. Both, for example, include masks and horseback riders, although in Calmon’s case these are worn by members of the embassy. Further, Calmon’s description of the king speaks to the kind of material wealth Afro-Mexicans also deployed in these performances to astound colonial audiences. This is how Calmon describes the king:

The king was dressed most ornately with rich gold embroidery and golden cords with bright gemstones. About his waist was a beautiful alligator made of the same cords and in such a fashion that it seemed real. On his head, a gold crown, and on his right hand, a gold scepter. On his left, a hat adorned with feathers. His shoes were of gold embroidery with bright gemstones. The cape, which fell from his shoulders, was of red velvet with gold borders, and lined with white fabric with beautiful roses embroidered on it.Francisco Calmon, Relação das fautíssimas festas que celebrou a Câmara da Vila de Nossa Senhora da Purificição, e Santo Amaro da Comarca da Bahia pelos augistíssimos desposórios da Sereníssima Senhora Dona Maria, Princesa do Brasil, com o Sereníssimo Senhor Dom Pedro, Infante de Portugal (Lisbon: Miguel Manescal da Costa, 1762), fols 11-12. The festival, held in 1761 in Santo Amaro, fifty miles away from the capital of Salvador, commemorated the wedding of the future Dona Maria I (1734-1816, r. 1777-1816), who was Princess of Brazil as heir apparent to the Portuguese throne, to her cousin Pedro III (1716-86, r. 1777-86) in 1760.

But where Calmon proved most useful was in expanding Díaz del Castillo’s “and then they went against the savages.” Calmon concludes his description of the Black king and queen performance by describing a mock battle:

Those in attendance were no less entertained by an attack, which, as the last act, the king’s guard, with their swords, charged against a group of Indians, who, dressed in feathers and armed with bows and arrows, ambushed the guard. There was such ardor between the two nations that they easily represented a vivid image of war.Calmon, Relação das fautíssimas festas, fol. 12.

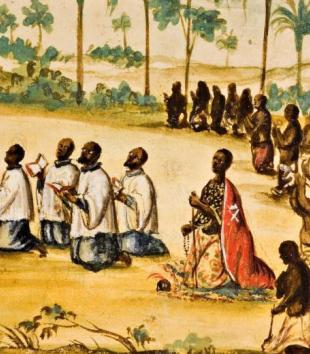

This mock battle is a known element of the performance of Black festive kings and queens dating back to the sixteenth century, and that it appears in Díaz del Castillo’s description demonstrates that it was brought to Mexico from the start of Spanish colonization. As Cécile Fromont has shown, the mock battle element of the performance was brought directly to the Americas from West Central Africa, where it was known as sangamento (Fig. 1).Fromont, “Dancing for the King of Congo.” It therefore also tells us something rare at the time about the Mexican performers: their ethnic origins. While most Africans being enslaved into the Americas at the time were being taken from Senegambia, this performance speaks to a different origin point for many Afro-Iberians, implying instead that they came from West Central Africa.In later centuries Afrodescendants with non-Congolese roots also adopted this festive tradition.

Fig. 1 Bernardino D’Asti (Italian, 18th century), Franciscan Missionary Blesses Warriors before a Sangamento, watercolor on paper, ca. 18th century, Italy, in Missione in prattica: Padri cappuccini ne Regni di Congo, Angola, et adiacenti, Biblioteca Civica Centrale, Turin, Italy, c. 1750, MS 457, fol. 18r. Courtesy of Biblioteca Civica Centrale.

Calmon pays little attention to the queen, simply stating that “The queen’s costume, which was in no way inferior, can be measured from the king’s.”Calmon, Relação das fautíssimas festas, fol. 12. In the late-eighteenth century, the Italian-born soldier and painter Carlos Julião (or Giuliani) (Turin 1740-Lisbon, 1811) did the opposite in Rio de Janeiro (Figs. 2-5). While Julião depicts a royal couple (Fig. 2) and a lone king (Fig. 3), he portrayed two additional queens (Figs. 4-5). Julião’s extra attention to queens may arise from the fact that queens wielded more power in confraternities and the performance than did kings.See Bettelheim, “Carnaval of Los Congo.” This is suggested by Díaz del Castillo’s “they [i.e., the rest of the Black entourage, possibly even the king] paid homage to the queen,” which is left out of Calmon’s account. Julião’s images thus counter Calmon’s phallocentric narrative and affirm the matriarchal narrative implied in Díaz del Castillo.

Fig. 2-5 Carlos Julião (Turin 1740-Lisbon, 1811), Afro-Brazilian Kings and Queens, watercolor on paper, in Riscos iluminados de figurinhos de negros e brancos dos Uzos do Rio de Janeiro e Serro Frio, ca. 1775, Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil Iconografia C.I.2.8, fols. 70-73. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Nacional do Brasil.

Julião’s images also speak to the kind of music making that was usually central to these performances, which in turn shed light on another Mexican lacuna. In 1610, after describing two Black performances in Mexico City for the city’s festivities for the beatification of Ignatius of Loyola (1491-1556, beatified 1609, canonized 1622), one staged by a Black confraternity, the Jesuit priest Andrés Pérez de Rivas (1575-1655) mentions, but does not describe:

eight Black dances, each of memorable artifice, which was owed to this poor people who, with extraordinary devotion, spent all they had to procure new dresses of damask and silk, all very well made, and because of this, and of the artifice of their dances, the curiosity of their costumes, and the sound of flutes and tambourines, brought great joy to the procession.Andrés Pérez de Rivas, Corónica y historia religiosa de la provincia de la Compañía de Jesús en Nueva España, vol. 1 (ca. 1600-50, first edition: Mexico City: Sagrado Corazón, 1896), 251.

It is hard to imagine eight dances being performed with just two instruments: flutes and tambourines. We know that Black music was far richer, and that Afrodescendants were allowed to incorporate a large swath of material culture into their performances for officially sponsored public festivals. As I did for the Black festive performance of kings and queens, in Sovereign Joy, therefore, I also looked elsewhere to try to broaden our understanding of Afro-Mexican musical ways.

Pairing Julião’s images with another set from Peru (Figs. 6-8), provides a notion of the expansive repertoire that characterized early modern Black music making, from African to European to American instruments. This visual record thus counters Pérez de Rivas’s sensuously impoverished rendering of early modern Black music making. Simultaneously, it also challenges a plethora of satirical mockeries of “Black cacophony” in the Iberian world, by showing that – even within those satires – early modern Black music was rich and complex. As Paul Gilroy put it in The Black Atlantic, these sources allow us to study “the power of music in developing black struggles by communicating information, organizing consciousness, and testing out or deploying the forms of subjectivity which are required by political agency.”Gilroy Paul, The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 1993), 36-37.

To give two examples of these hostile renderings of Black music, the postal inspector Alonso Carrió de la Vandera (also known as Concolorcorvo), described Black music as follows in his satirical travel guide of South America, El lazarillo de ciegos caminantes (Guide for blind walkers, Lima, 1775/6):

The Blacks’ entertainments are the most barbaric and vulgar one can imagine. Their song is a howl. Its unpleasant sound can be deduced by just looking at their instruments. The jaw of an ass, defleshed, with its teeth loose, are the cords of its principal instrument, which they scratch with a ram’s bone, antler or another hard stick, with which they make fastidious and unpleasant alto and soprano noises, which causes people to cover their ears and the donkey, which are the most stupid and least easily frightened animals, to run. Instead of the pleasant drums of the Indians, Blacks use a hollow trunk, to whose ends they affix a rough hide.Alonso Carrió de la Vandera, El lazarillo de ciegos caminantes, edited by Antonio Lorente (1775/6, reprint: Medina. Caracas: Ayacucho, 1985), 175. See Ruth Hill, Hierarchy Commerce and Fraud in Bourbon Spanish America: A Postal Inspector's Exposé(Nasville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2005).

Although Carrió de la Vandera describes Black music as “the most barbaric and vulgar one can imagine,” he still speaks of Black music’s sophistication of altos and sopranos. Moreover, the donkey jaw Carrió de la Vandera dismisses as “fastidious and unpleasant” sounding is a key instrument of Son Jarocho, an Afro-Mexican music genre with colonial roots. Carrió de la Vandera’s testimony shows that it was also in use in South America and thus also allows us to see musical connections across the African diaspora.

Another example underscores, as Julião’s images do, the plethora of instruments Afrodescendants employed in their music making. On October 6, 1730, the weekly satirical Folheto de ambas Lisboas (Pamphlet of Both Lisbons) described the music one of the city’s confraternities had played in their feast celebration in terms similar to Carrió de la Vandera’s:

There were myriad instruments in the churchyard, with a bizarre dissonance; because there were three marimbas, four piccolos, two fiddles, more than three hundred berimbaus, tambourines, African drums, the instruments they use.1

By pairing these satirical renderings with visual culture, and reading the satire critically, I was able to recover Black music from this negative evidence. This methodology is required by the myriad negative assessments of Black festive culture found in the colonial archive, as I analyze in chapter two of Sovereign Joy. This approach allows us to bring Black voices – rather than white ones – to the fore—in other words, to pull down the satirical screen and let the Black actors sound.

- 1Anonymous, Folheto de ambas Lisboas, no. 7 (Lisbon: Officina da Música, 1731), fol. 3.

The Peruvian images come from bishop Baltasar Jaime Martínez Compañón’s (1737-97), monumental nine-volume Trujillo del Perú (1782-85), which one scholar has called a “paper museum” of late colonial northern Peru.Emily Berquist Soule, The Bishop’s Utopia: Envisioning Improvement in Colonial Peru (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014). Comprised of 1411 watercolors and 20 musical scores, the images were commissioned by Martínez Compañón, who wanted to present a book that described the geography, peoples, and cultural practices of his ecclesiastical territory (northern Peru ) to Charles III of Spain (b. 1716, r. 1759-88). We see some of the same instruments in Martínez Compañón as we do in Julião (Figs. 2-5). For example, Figure 6 shows the marimba, a xylophone that has been linked to the cultures of West Central Africa.See Brian Schrag, Artistic Dynamos: An Ethnography on Music in Central African Kingdoms (London: Routledge, 2021). The two depictions of marimbas, however, are different—while Martínez Compañón’s is set on a box, Julião depicts a balafon, which drew its sound from gourds. The image also depicts Afro-Peruvians playing castanets, a Spanish instrument we likewise see in Julião’s illustrations. Figure 7, moreover, portrays Afro-Peruvians playing the vihuela, a lute-like Spanish instrument of medieval origin with the body of a guitar that is the precursor of the da gamba family of instruments.See Bettina Hoffmann, The Viola da Gamba, translated by Paul Ferguson (London: Routledge, 2018). A contemporary description states that Afrodescendants strummed this instrument “from bottom to top.”João Sardinha Mimosa, Relacion de la real tragicomedia con que los padres de la Compañia de Jesus en su colegio de S. Anton de Lisboa recibieron a la Magestad Catolica de Felipe II de Portugal, y de su entrada en este Reino, con lo que se hizo en las Villas, y Ciudades en que entró (Lisbon: Jorge Rodriguez, 1620), fol. 58r. English in Lisa Voigt, “All the World on Stage: Performance and Global Knowledge in Early Modern Portuguese Festivals,” Revista de Estudios Hispánicos 55, no. 1 (2021): 41-64. In the foreground this figure depicts a reco reco drum unique to Peru, but which combines two African instruments: the drum and the reco reco. It is played by scraping the middle reco reco with the left hand and beating the gourd drum with the right. Figure 8, on the other hand, represents two figures dancing the zamacueca, the precursor of today’s cueca, the national dance of Peru, Chile, and Bolivia. Martínez Compañón’s images thus illustrate the kind of creolization that characterized Afrodescendants’ festive practices, whereby they created a new culture from the mixing of African, European, and Amerindian cultural elements. This marks Afrodescendants’ festive traditions as what Fromont has called “spaces of correlation” where subjects produce “cultural creations such as narratives, artworks, or performances that offer a yet-unspecified domain in which their creators can bring together ideas and forms belonging to radically different realms, confront them, and eventually turn them into interrelated parts of a new system of thought and expression.”Cécile Fromont, The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014), 15.

Julião and Martínez Compañón’s images help us counter the satirical assessment of colonial Black music by broadening our view of those satirical renderings and showing the myriad of instruments – of both African and European origin – Afrodescendants used in their early modern music making. If we heed Tina M. Campt’s invitation “to ‘listen’ rather than simply ‘look at’ images,” we may even hear this music through these images.Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017), 6.

Mexico City’s festivities for the beatification of Ignatius of Loyola included a Black performance that spoke not only to the material wealth Afro-Mexicans deployed in these performances, but also to the cultural literacy they put into action in them. According to Pérez de Rivas:

After seeing [the first] performance, the procession came right away to another, also by Africans [morenos], recently brought to this Kingdom from Africa, who brought an elephant of marvelous size and beauty. It was a wonder to see its figure and form so naturally done. All this machinery was set upon wheels that moved with great ease. Up above this animal there was a Black king, with a scepter in one hand and a crown on his head, convincingly representing the king of Africa. It was a great thing to behold how this beast made reverence to God’s sovereign majesty when it approached the eucharist. It then moved aside to let the people through and do something which caused no less joy or admiration, for its belly was hollow and roomy, like the Trojan horse, and like that of soldiers, this one of rockets, mortars, and bombs, which lit with a secret cord, blew two bombs before those outside saw it, and blowing up the elephant, shot from there and its eyes and trunk, with such speed and force, so many rockets that they caused great admiration and joy.Pérez de Rivas, Corónica y historia religiosa, 1:250-251.

This performance followed a more European tradition. A similar performance had been staged in 1554 in Benavente, Zamora, Spain, for Phillip II (1527-98, r. 1556-98):

The first performance to enter was that of a powerful elephant, very natural and beautifully made. The head of this elephant was the size of a horse with its neck and forelegs, and the other half a horse at its rump; so natural, that it was a marvel to behold. On top there was an African, only wearing a shirt, with his right sleeve rolled up, and an arrow in his hand, imitating in his posture and attire, the Indians of West Africa.Andrés Muñoz, Viaje de Felipe Segundo [1554] (Madrid: Sociedad de Bibliófilos Españoles, 1877), 45.

Likewise, a comparable performance featured in the Paris Royal Opera 1626’s staging of Le Grand Bal de la Douairière de Billebahaut (Fig. 9). Kate Lowe and Noémie Ndiaye have argued that this European performative genre, of representing Africa through the trope of the elephant, emerged as an imitation of African embassies to Europe.Kate Lowe, “‘Representing Africa: Ambassadors and Princes from Christian Africa to Renaissance Italy and Portugal, 1402–1608,” Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 17 (2007): 101-128; Noémie Ndiaye, “The African Ambassador’s Travels: Playing Black in Late Seventeenth-Century France and Spain,” in Transnational Connections in Early Modern Theatre, ed. M. A. Katritzky and Pavel Drábek (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2020), 73-85. While that was clearly the case for the 1761 festival Calmon describes, insofar as it imitated African embassies to Brazil, African embassies to Europe did not feature elephants, as African elephants, unlike Asian elephants, are not domesticated.On African embassies to Brazil, see Lisa Voigt, “Representing an African King in Brazil,” in Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance Representation and the Making of Black Atlantic Tradition, edited by Cécile Fromont (State College: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019), 75-91. This performance, instead, falls more squarely in what Peter Mason has called the exotic genre, which lacks geographic specificity, as Muñoz’s last line from Benavente attests: “Indians of West Africa.”Peter Mason, Infelicities: Representations of the Exotic (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998), 40. Performances like this one, however, may hold the key as to how the elephant came to represent Africa in visual allegories of the four continents.See, for example, Maryanne Cline Horowitz and Louise Arizzoli, eds., Bodies and Maps: Early Modern Personifications of the Continents (Leiden: Brill 2021). Sovereign Joy’s cover image, Africa (ca. 1809) by the mixed-race Afro-Brazilian painter José Teófilo de Jesus (ca. 1758-1847) may demonstrate precisely this (Fig. 10). Where Africa had been represented by a lion or a crocodile in previous centuries, in the early nineteenth century the elephant came to take their place.

The adoption of the European performance tradition in the Mexican festivities described by Pérez de Rivas demonstrates Afrodescendants’ capacity for what Mary Louise Pratt has termed autoethnography, or the capacity to represent themselves “in ways that engage with representations others have made of them.”Mary Louise Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” Profession (1991): 33-40, p. 35. In other words, “presentations that the so-defined others construct in response to or in dialogue with” how “European metropolitan subjects represent to themselves their others.”Pratt, “Arts of the Contact Zone,” 35; emphasis in the original. In this performance, Afro-Mexicans represented themselves as Europeans had depicted them.

Because this performance dialogued so eloquently with a European repertoire, I doubt that the performers had been “recently” enslaved into Mexico as the Pérez de Rivas contends. If they were indeed recently enslaved Africans, this would show knowledge of this European tradition crossing to the Americas from Africa. This is not necessarily impossible and further research may be able to confirm it. But given that the preceding performance, of African “savages” carrying the Eucharist with their king, was staged by a confraternity made up of Black Creoles (morenos criollos), I am inclined to believe that this second performance was also staged by an Afro-Mexican group of Afrodescendants with longer diasporic trajectories. The author needed them to be “Africans recently brought to this Kingdom from Africa” to “convincingly [represent] the king of Africa” as this gave the performance authenticity. The way Pérez de Rivas presents the performance, however, hides the full depth of the performers’ agency as it is only viewed as a performance devised and staged by Afrodescendants that we can see and appreciate the meaning of its autoethnography. That autoethnography is not only about confronting European audiences the representation they had developed of Afrodescendants. It is also and more importantly about the performers seeing themselves not as Africans, but rather as Black Creoles that could stage this performance as an allusion to their geographic origins. The performance is thus a staging of the actors’ subjectivity as Black Creoles capable of engaging in the exotic genre to which Europeans had sought to confine Africa, Asia, and the Americas.See Mason, Infelicities. It is through a sensitivity to the historical awareness of performers that we must see the performative genre of Black festive kings and queens and many other Afro-diasporic festive customs.

The Black festive tradition and its visual record underscore how Afrodescendants engaged with early modern material culture to stage performances that spoke about their identity in ways contemporary authors may have not entirely comprehended. Sovereign Joy thus broadens our understanding of the centrality of material culture to Afrodescendants’ lives. The performance of Black festive kings and queens showcases early modern Afrodescendants’ religious, political, and material agency and subjectivities—in other words, how Afro-Catholic subjects set devotional and cultural priorities for the confraternities they founded to ameliorate their colonial conditions. The performance also speaks of the joy the Afro-Catholic subjects wrought. This joy was rooted in both African ways of life and Christian joy (gaudium). Finally, in an increasingly racialized, anti-Black world, this tradition highlights how the same religion that was used to justify African slavery, also provided interstices that allowed Afrodescendants to shape that religion and use it to do more than merely survive—to form community, build safety nets, develop Afro-Catholic performance culture, religiosity and subjectivity they could call their own.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.con.2023.2

1. Miguel Valerio, "Resoundings of Early Modern Afro-Catholic Festive Culture," Constellation, MAVCOR Journal 7, no. 1 (2023), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2023.2.

Valerio, Miguel. "Resoundings of Early Modern Afro-Catholic Festive Culture." Constellation. MAVCOR Journal 7, no. 1 (2023), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2023.2.