Ben Nourse is an assistant professor of Buddhist Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Denver and a senior fellow with the Andrew W. Mellon Society of Fellows in Critical Bibliography at the Rare Book School. His research focuses on Tibetan Buddhist history and literature. His book, The Power of Publishing in Early Modern Tibetan Buddhism, is forthcoming in Lexington Books' Studies in Modern Tibetan Culture series.

Introduction

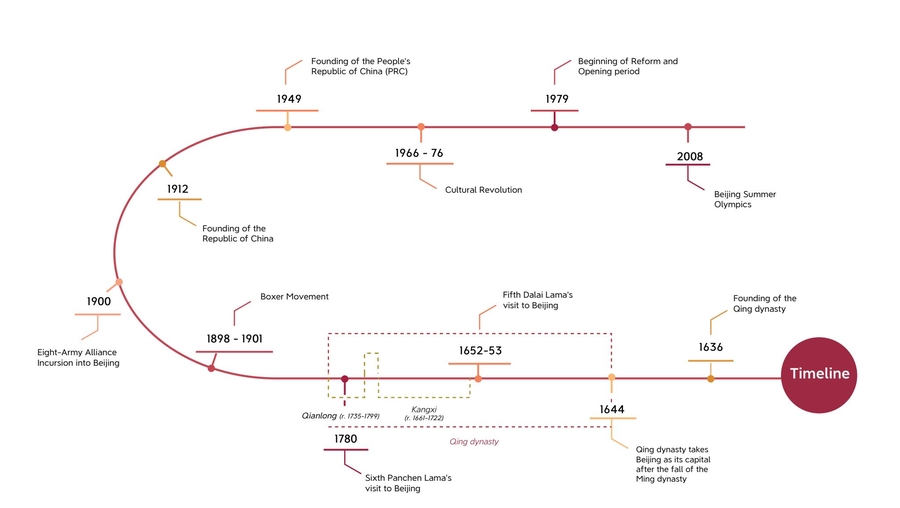

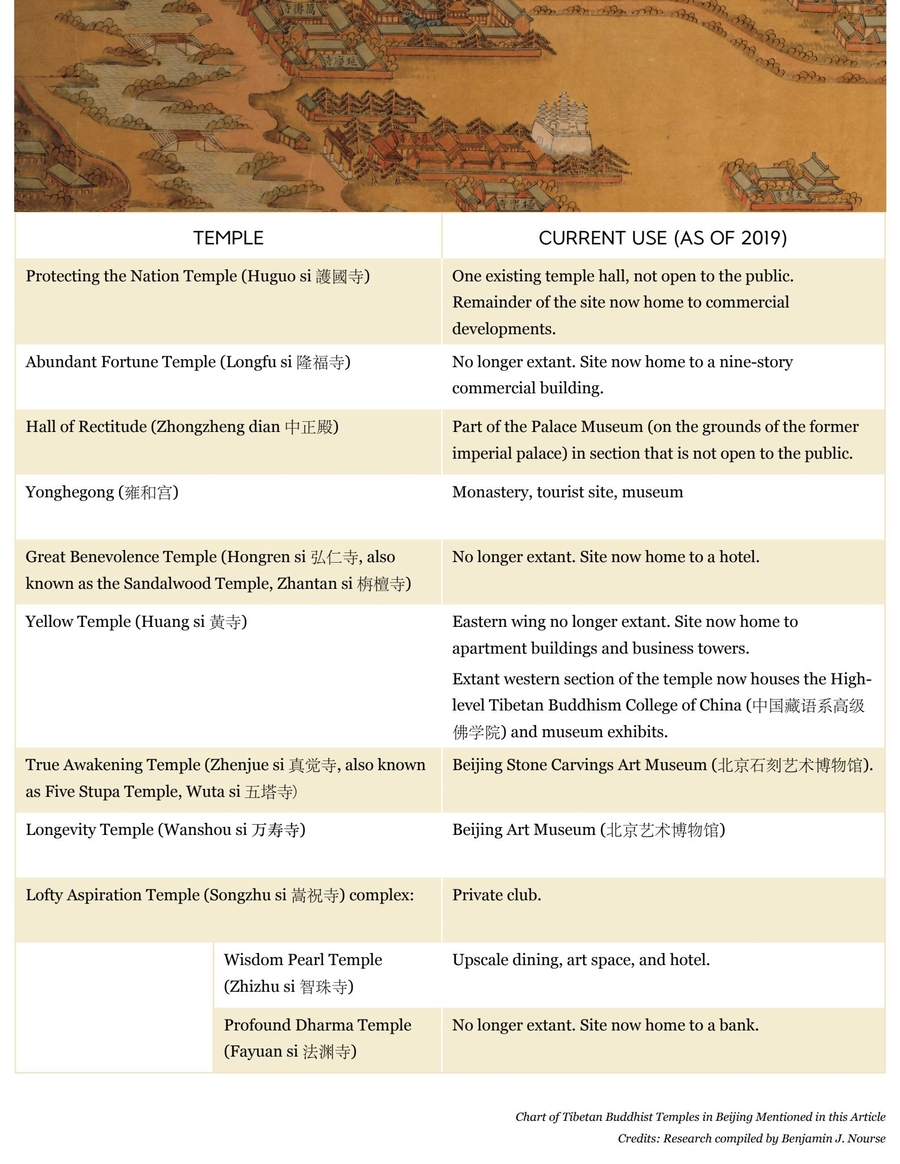

This paper is concerned with the once thriving Tibetan Buddhist temples and monasteries that dotted Beijing, especially during the Qing dynasty (1636-1911) which took Beijing as its capital beginning in 1644. Over the course of several stays in Beijing within the last fifteen years, but particularly during a week in August 2019, I have mapped and documented the sites of Qing-era Beijing's more than fifty Tibetan Buddhist temples.1This article analyzes the changing use and understanding of these temple sites from the Qing period to the present.

- 1This research was made possible by a Fulbright-Hays Fellowship to China in 2010-11 and a University of Denver Internationalization Grant in 2019.

Beijing is a vibrant and modern city, and as with other cities around the world today, its growth and development have been built at a heavy cost to its history. This cost has been acute in China, where the political movements of the twentieth century often glorified the demolition of the past, a sentiment that reached a high point during the Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 70s. However, the destruction of old Beijing was most fully realized in the hyper-modernization and construction that have marked the Reform and Opening (Gaige kaifang 改革开放) period since 1979.

Due to this history, many of Beijing's Tibetan Buddhist temples are now no longer extant, only traces of them survive in the names of streets and subway stops. Others continue to exist—in whole, part, or reconstructed—but have taken on new functions as museums, tourist destinations, schools, upscale restaurants, or shopping centers. As Robbie Barnett has argued in Lhasa: Streets with Memories, the streets and edifices of a city can be read as texts which provide glimpses of its multilayered history.1Pushing this analogy further, Lauret Savoy in her book Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape likens the American landscape to a palimpsest, where "layers upon layers of names and meanings lie beneath the official surface."2From this perspective, cities are not merely texts to be straightforwardly read, but are layered texts—palimpsests—in which some aspects of the page are obscured, given new meaning, or completely concealed by later layers of text and image. In this article, I attempt to pull back some of the layers of contemporary Beijing, but also to understand, to read, the palimpsest and its meanings in the present. In the modern context, I also draw on Birgit Meyer and Marleen de Witte’s identification of two processes often at work when historical religious sites become recognized sites of cultural heritage: the heritagization of the sacred and the sacralization of heritage.3Some Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples have been subject to a process of heritagization of the sacred, in which their contemporary value as heritage sites managed by the state often overshadows their historical function and meaning. Other former temple sites have been subject to a sacralization of heritage, in which religious or spiritual significance is projected onto a site as a way to enhance its appeal. These two processes, discussed in more detail below, inscribe new meanings onto Tibetan Buddhist temple sites and attempt to shape new identities for the communities that visit them.

- 1Robert Barnett, Lhasa: Streets with Memories (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 2 and 123.

- 2Lauret Savoy, Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape (Berkeley, California: Counterpoint Press, 2015), 104.

- 3Birgit Meyer and Marleen de Witte, “Heritage and the Sacred: Introduction,” Material Religion 9, no. 3 (2013): 277. I thank an anonymous reviewer for bringing this source to my attention.

While both Qing-era and present-day Beijing can be seen as cosmopolitan cities, the specific ways in which that identity was and is practiced and promoted within the grounds of Tibetan Buddhist temples is quite distinct between the two time periods. Unlike the previous Ming dynasty, the Qing dynasty rulers were not from the Chinese heartland, nor were they Han (the largest ethnic group in China). The Qing instead hailed from an area to the northeast of China and described themselves as "Manchu" people. Prior to the last quarter century, most historical studies put forward the thesis that the Qing largely assimilated to Chinese culture ("sinicized") and thus lost their ethnic distinctiveness. In the last twenty-five years, however, a new perspective on Qing history has emerged which is often referred to as "new Qing history." A key aspect of scholarship in this vein is that it does not privilege a China-centric, or Han-centric, understanding of the Qing. Instead, it characterizes the Manchu Qing as maintaining a separate ethnic identity and, moreover, as utilizing and identifying with a range of cultures and languages, especially those of Inner Asia (that is, the regions north and west of the Han Chinese cultural area, including Manchuria, Mongolia, Xinjiang, and Tibet) as it built a multi-ethnic, multi-lingual empire.1

- 1Some of the characteristic elements of "new Qing history" are summarized by Joanna Waley-Cohen in “The New Qing History,” Radical History Review 88, no. 1 (2004): 193-206, and by Ruth W. Dunnell and James A. Millward in their "Introduction" to New Qing Imperial History: The Making of the Inner Asian Empire at Qing Chengde, ed. James Millward, Ruth Dunnell, Mark Elliot, and Philippe Forêt (London: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004), 3-4.

In line with new Qing history, I examine Tibetan Buddhist temples in the Qing capital as sites through which the Qing court projected a multi-ethnic imperial identity, often through patronage and ritual. This brought Tibetan Buddhists (who were not limited to Tibetans, but also included Mongol, Monguor, and Manchu people who practiced Tibetan-derived forms of Buddhism)—along with their religions, cultures, and languages—into the imperial capital. Far from being completely sinicized by their move to Beijing, the Qing instead molded parts of Beijing into an Inner Asian city.

By contrast, Tibetan Buddhist temples in modern Beijing serve as sites transformed largely for the consumption of culture and commodities by middle and upper-class consumers and tourists, both domestic and international. In addition, they are useful for promoting particular versions of history that support claims of ethnic harmony and Chinese nationalism. These new uses of Tibetan Buddhist temples in Beijing are in line with the movement of the Chinese Communist Party toward forms of legitimacy grounded on their ability to grow the Chinese economy (largely through selective capitalist market reforms) and on a form of Chinese nationalism that promotes a view of Chinese history in which all current ethnic minorities have participated in a unified Chinese nation for centuries. This view of history often privileges Han Chinese assumptions and attitudes about the Chinese state and Chinese culture. This article therefore demonstrates how religious sites, including Buddhist temples, do not merely serve as the backdrop for religious practice, but become sites for cultural construction and the narration of history. As with a palimpsest, there is an obscuration and even erasure of what has come before in order to use the same space to present something different. In a palimpsest, while the age and feel of the paper still conveys meaning, the primary meaning is conveyed in the new words that cover the page. Likewise, the physical grounds of former Tibetan Buddhist temples in Beijing carry meaning, but that meaning can be filtered and transformed through the placement of new structures and symbols on these sites.

Searching for Protecting the Nation Temple and Checking in to the Nostalgia Hotel

Contemporary Beijing is a wonderful, vibrant city full of life and creativity. People might also think that it is a place steeped in history because of famous sites like the Forbidden City (Zijin cheng 紫禁城) and the Temple of Heaven (Tiantan 天壇). But apart from these few large imperial sites, there is not much of old Beijing (by which I mean the built environment that existed prior to the twentieth century) that still exists today. Most of the city has been demolished or destroyed and rebuilt—effaced and re-inscribed—with new physical structures overlaid onto the ancient city plan.1This is likewise true for the Tibetan Buddhist temples of the city. This was apparent from my first full day in Beijing during a trip in August 2019 when I visited Protecting the Nation Temple (Huguo si 護國寺). While Protecting the Nation Temple was once one of the largest temple compounds in the city, I found only one surviving structure which was in a dilapidated state. Moreover, this remaining temple hall was not immediately noticeable among the new commercial developments that now surround it on all sides.

- 1As Shuishan Yu notes, "From the 1950s onwards, vast areas of traditional hutong (alley) neighbourhoods were cleared, together with the city walls and many temples, palaces, shrines and gates, to make way for the construction of new socialist monuments." Shuishan Yu, "Courtyard in Conflict: The Transformation of Beijing’s Siheyuan During Revolution and Gentrification," The Journal of Architecture 22, no. 8 (2017), 1338. Statistics on how much of the architectural structures of Old Beijing exist today are hard to find, but according to one estimate only about one quarter of the hutong(traditional alleyways with their courtyard housing) that existed in Beijing prior to 1949 have survived into the twenty-first century (John Zacharias, Zhe Sun, Luis Chuang, and Fengchen Lee, "The Hutong Urban Development Model Compared with Contemporary Suburban Development in Beijing," Habitat International 49 (2015): 261.

In the compound next to the temple hall was the Nostalgia Hotel (the Chinese name is Shiguang manbu 时光漫步, "time stroll" or "stroll through time," Fig. 1). This seemed appropriate. As an historian who has spent considerable time researching Qing-period Beijing, I felt a certain sense of nostalgia—an ache for the loss of the majority of this temple's buildings as well as a wish that I could go back in time and experience this space as it existed at the height of the Qing dynasty. This is not to say that I wish we could actually roll back time, or remake Beijing as it was. It is more a symptom of certain types of historical study in which we are forever cut off from a direct encounter with the subject of our work. We know our subject indirectly, obliquely, and we write history from our perspectives in the present. Perhaps the best we can do is to check in to the Nostalgia Hotel for a time and closely read our palimpsest for glimpses of what once existed from the evidence that remains. At the same time, we need to be attentive to the ways in which the concerns of the present shape historical understanding. Meyer and de Witte offer a similar assessment of the study of sacred heritage, writing that “Heritage refers to the past, but it is not automatically and directly inherited from the past.”1They argue that we thus need to be attentive to the processes of heritage formation, or “heritagization,” which ascribe new meanings and values to heritage sites. In order to better understand the heritagization of Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples over the last several decades, this article will compare recent heritage formation with the physical state and meaning of Tibetan Buddhist temples during the Qing era.

- 1Meyer and de Witte, “Heritage and the Sacred,” 276.

Fig. 1 The Nostalgia Hotel just to the northwest of the former site of the Protecting the Nation Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

The attempt to reconstruct old Beijing, to peel back the layers and see what was once there, is aided by documentary and physical evidence that still exists from previous eras. Such evidence includes historical accounts of the city, stelae, monuments, artwork, and maps. Historical maps, in particular, can provide us with a basic orientation, such as a detailed map of the city produced under the Qianlong emperor in 1750 titled Complete Map of the Capital (Jingcheng quan tu京城全圖) or a mid- to late-nineteenth-century map titled Complete Map of Beijing (Beijing quan tu 北京全圖).1These cartographic sources indicate the locations and footprints of nearly two dozen Tibetan Buddhist temples within the city or in the near suburbs. On these maps we can find Protecting the Nation Temple just to the northwest of the Forbidden City (Figs. 2 and 3), the imperial palace at the heart of Beijing.

- 1A facsimile reproduction of The Complete Map of the Capital (Jingcheng quan tu京城全圖) of 1750, has been published as Jia mo Qianlong jing cheng quan tu 加摹乾隆京城全圖 (Beijing: Beijing Yanshan chu ban she, 1996). It has also been digitized by the National Institute of Informatics in Japan, for which see the 乾隆京城全図 on the "National Institute of Informatics - Digital Silk Road Project Digital Archive of Toyo Bunko Rare Books" website, http://dsr.nii.ac.jp/toyobunko/II-11-D-802/, doi: 10.20676/00000211. The Complete Map of Beijing (Beijing quan tu北京全圖), c. 1861, has been digitized by the Library of Congress (Geography and Map Division, call no. G7824.B4 1887 .L5), http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7824b.ct003294.

Fig. 2 Complete Map of Beijing (c. 1861) with added bright red rectangle indicating the location of Protecting the Nation Temple. Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

Fig. 3 Detail of Complete Map of the Capital (1750), a map of Beijing produced under the Qianlong emperor, showing Protecting the Nation Temple. Source: Jia mo Qianlong jing cheng quan tu 加摹乾隆京城全圖 (Beijing: Beijing Yanshan chu ban she, 1996), 9-3 and 9-4.

As seen in the rendering of Protecting the Nation Temple in figure 3, most of the architectural features and layout of these monasteries was in the style of traditional Chinese Buddhist temples, though with some modifications. The Chinese elements included a symmetrical design along a north-south axis. The main temple halls were generally situated on this axis, including an entry hall that contained statues of the Four Guardian Kings, while monks' residences were located along the sides of the complex. Additionally, the entrance courtyard of these monasteries often contained a drum tower and bell tower. The buildings themselves were made of wood construction with sloping roofs.1None of these elements are common in Tibetan Buddhist architecture, especially that of central Tibet (Fig. 4).2Their use in Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples was due, in part, to the fact that many of these temples had originally been Chinese Buddhist temples, adding yet another layer to our reading of these sites. Others were renovated from private residences (the famous Yonghegong being the main example of this). On the other hand, some halls within these temples were designed to mimic aspects of Tibetan monasteries, such as halls with square layouts representing a mandala and containing concentric upper-floor galleries around a skylight.

- 1On the Han Chinese Buddhist architecture of Tibetan Buddhist temples in Beijing, see Lucie Olivová, "Tibetan Temples in the Forbidden City (An Architectural Introduction)," Archiv orientální (2003): 409-432, and Dan Liu, "Patronage and Meaning of Tibetan Buddhist Temples Decreed by the Qing Emperors in Central China in the Early and Middle Qing Dynasty" PhD dissertation, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, 2010, especially chapter 7: 127-153. Similar elements can be seen in Tibetan Buddhist temples of Wutaishan, as discussed in Isabelle Charleux, "Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist Architecture and Iconography on Wutaishan, Seventeenth to Early Twentieth Centuries," Studies in Chinese Religions 5, nos. 3-4 (2019): 256-305.

- 2For a description of central Tibetan temple architecture, see André Alexander, The Temples of Lhasa: Tibetan Buddhist Architecture from the 7th to the 21st Centuries (Singapore: Times Editions – Marshall Cavendish, 2005), especially the useful summary on pages 23-24.

Fig. 4 An assembly hall at Drepung Monastery outside Lhasa, Tibet, with whitewashed stone construction, a penbé (Tib. span bad) frieze along top, distinct inset windows framed in black, and a flat roof, 2019. Photo by author.

Upon entering the temple halls, one would find furnishings and artwork that drew on those seen in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. Some of these furnishings came from the Tibetan plateau, while many items were also made by the workshop housed in the Hall of Rectitude (Zhongzheng dian 中正殿), the center of Tibetan Buddhist activity within the Forbidden City. Thus, the outer appearance of these temples was in many ways congruent with Chinese architecture seen elsewhere in the city. However, anyone who entered the halls of one of these Tibetan temples would be immediately struck by the many statues and paintings whose style and subject matter were quite distinct from a Han Chinese Buddhist temple. This would be particularly true in the depiction of many tantric deities and also the presence of colorful scroll paintings known as tangka (Tib. thang ga, ཐང་ག). characteristic of the Tibetan tradition. Another striking difference would be the monks' dress and ritual practices. Whereas Chinese Buddhist monks often wear black or grey robes, Tibetan Buddhist monks often wear maroon or red robes. They also chant in different languages and play different liturgical instruments.1

- 1Susan Naquin, in Peking: Temples and City Life, 1400-1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000), 210, notes that a mid-nineteenth-century Chinese literati visitor to the Five Stupa Temple (Wuta si) "climbed up onto the platform to inspect the five stupas and listened to the distinctive sound of the lamas practicing on their Tibetan horns."

Protecting the Nation Temple and most of the other Tibetan Buddhist temples in the Beijing area thrived on imperial patronage during the height of the Qing dynasty in the eighteenth century.1These temples were also sites of cosmopolitan exchanges between Tibetans, Manchus, Mongolians, and Chinese. The grounds of Protecting the Nation Temple and Abundant Fortune Temple (Longfu si 隆福寺), for example, were the sites of bustling monthly market fairs which featured goods brought to the capital from visiting Mongol tribute missions.2These temples also hosted booksellers who sold Tibetan, Manchu, Mongolian, and Chinese books.3Protecting the Nation Temple even produced its own woodblock editions of Tibetan Buddhist books.4Likewise, many other temples in the capital produced an abundance of literature, translations, art, and ritual performances, all of which were often the result of multi-ethnic collaborations.5 Even the sign boards and stelae at many of these temples, often quadrilingual (Manchu, Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian), evince the multicultural character of these Qing temples and of the empire itself (Fig. 5).

- 1Zhang Yuxin, Liu Limei, Wang Hong, and Zhang Shuangzhi, Zangzu wen hua zai Beijing (Beijing: Zhongguo Zang xue chubanshe, 2008), 144. Robert James Miller, Monasteries and Culture Change in Inner Mongolia (Wiesbaden: O. Harrassowitz, 1959), 76-78.

- 2Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 29-31, 75. Hui-min Lai, "The Economic Significance of the Imperial Household Department in the Qianlong Period," Global COE Hi-Stat Discussion Paper Series gd12-252, Institute of Economic Research, Hitotsubashi University (2012): 10. Miller, Monasteries and Culture Change in Inner Mongolia, 78.

- 3Evelyn S. Rawski, “Qing Publishing in Non-Han Languages,” in Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China, ed. Cynthia J. Brokaw and Kai-wing Chow (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 310-311.

- 4Examples of two publications from Protecting the Nation Temple are held by the University of Wisconsin Libraries: Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, Bder gshegs bdun gyi mchod pa'i chog sgrigs yid bzhin dbang rgyal (Beijing: Da long shan hu guo si 大隆善護國寺, 1690), University of Wisconsin Special Collections, Lessing collection, no. 71, and Ngag dbang blo bzang rgya mtsho, Dpal brtan chen po bcu drug gi mchod pa rgyal bstan 'dzad med nor bu (Beijing: Da long shan hu guo si 大隆善護國寺, 1711), University of Wisconsin Special Collections, Lessing collection, no. 18.

- 5For example, the publication of Blo bzang chos kyi rgyal mtshan, Byang chub lam gyi rim pa'i dmar khrid thams cad mkhyen par bgrod pa'i bde lam (Beijing: Songzhu si, mid-eighteenth century), University of Wisconsin Special Collections, Lessing collection, no. 329, involved a staff that included Mongols, Monguors, and Chinese. See the colophon at ff. 95r.1-97r.1. The text of the colophon is also reproduced in Manfred Taube, Tibetische Handschriften und Blockdrucke (Weisbaden: Steiner, 1966), vol. 3, entry no. 2592.

Fig. 5 A painter refreshes the quadrilingual (Manchu, Chinese, Tibetan, and Mongolian) main sign board for Yonghegong Monastery, 2011. Photo by author.

Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples began to decline as the Qing empire itself declined during the nineteenth century. Several were severely damaged in the aftermath of the Boxer Movement (Yihetuan yundong義和團運動), a movement to rid China of foreign influences that swept through north China at the very end of the nineteenth century. The Boxers attacked foreigners, including Chistian missionaries and the foreign legations in Beijing. In 1900, a military force of eight foreign powers launched an incursion into Beijing to put down the Boxer Movement, resulting in significant destruction to portions of old Beijing. After the fall of the Qing and the establishment of the Republic of China in 1912, many Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples fell into disrepair, housing only a handful of monks or none at all.1After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, cultural heritage was often targeted as a direct obstacle to ushering in socialism. Temples were transformed to uses deemed more appropriate to advancing socialist society, such as factories or warehouses. These attitudes toward cultural heritage culminated during the turbulent era known as the Great Proletariat Cultural Revolution (Wenhua Dageming 文化大革命, ca. 1966-1976), when some temples were reduced to rubble by the zealous revolutionaries known as the Red Guards.

- 1Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 75 n. 77.

What warfare, neglect, and political zealotry did not destroy, later economic development and urban modernization, beginning with the Reform and Opening period initiated in the late 1970s, has further obscured and built over. Returning again to Protecting the Nation Temple, today the one surviving temple hall is not only next to the Nostalgia Hotel, but the main courtyard of the temple has now been developed as a shopping and dining center, one of the chic New Heaven and Earth (Xin tian di 新天地) shopping complexes, anchored (when I was there in 2019) by a Starbucks coffee shop (Fig. 6). Today you can sip coffee in the shadow of the single remaining temple hall (Fig. 7). The hall itself is not visible from the main street that passes in front of the former temple complex. A much more conspicuous clue that this was the site of a former temple is the continuing use of the temple's name. The main east-west street in the area is named after the temple (Protecting the Nation Temple Street, Huguosi jie 护国寺街), as are a number of the businesses, including the Protecting the Nation New Heaven and Earth complex (Huguo xin tian di 护国新天地) and the Protecting the Nation Temple Snacks restaurant (Huguo si xiaochi 护国寺小吃, Fig. 8).

Fig. 6 The Protecting the Nation New Heaven and Earth dining and shopping center on Protecting the Nation Temple Street, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 7 Café tables in front of the only remaining temple hall of Protecting the Nation Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 8 Protecting the Nation Temple Snack restaurant (with green sign) on Protecting the Nation Temple Street, 2019. Photo by author.

As Protecting the Nation Temple demonstrates, often the most obvious way that the elements of Beijing's Tibetan Buddhist past continue to be legible in contemporary Beijing is in place names around the city, including street names and subway stops. Probably the most well-known example is the subway stop named Yonghegong (雍和宫, given in English as both "Yonghegong" and "Lama Temple") at the intersection of subway lines 2 and 5, named after a Tibetan Buddhist monastery founded in 1744.1Streets named after temples are common. In addition to Protecting the Nation Temple Street, there are also Yellow Temple Street (Huang si dajie 黃寺大街), Longevity Temple Road (Wanshou si lu 万寿寺路), Five Stupa Temple Road (Wuta si lu 五塔寺路), and Universal Passage Temple Front Alley (Puding si qian xiang 普渡寺前巷), all named after Tibetan Buddhist temples in the capital (Fig. 9).

- 1Line 2 actually follows the old Beijing city wall, which was largely torn down to make way for transportation infrastructure in the 1960s, so many of the stops along this line take their name from the old city gates that once stood at the respective stops.

Fig. 9 Street signs for (clockwise from top left): Yellow Temple Street, Longevity Temple Road, Five Stupa Temple Road, and Universal Passage Temple Front Alley, 2019. Photos by author.

While Protecting the Nation Temple still retains one temple hall, all that remains of Great Benevolence Temple(Hongren si 弘仁寺, also known as the Sandalwood Temple, Zhantan si 栴檀寺) today are references to its name and history by one business that exists today in the temple's former location. Great Benevolence Temple was once one of the most important Tibetan Buddhist temples in the capital. In the late seventeenth century, the Kangxi emperor would visit the temple at the New Year to receive blessings and teachings from lamas visiting from Tibet.1In the eighteenth century, it was the site of large rituals sponsored by the emperor and performed by thousands of Tibetan Buddhist monks.2It was home to one of the most sacred Buddhist objects in Beijing, a sandalwood Buddha statue said to have been brought from India. The sandalwood statue was one of the main attractions for Tibetans and Mongolians, especially elite religious and political figures, visiting Beijing during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.3

- 1A typical event of this type is described by Ngawang Lobzang Chöden (1642-1714), the First Changkya Lama, in his autobiography: Ngag dbang blo bzang chos ldan, Rnam thar bka' rtsom, in Ngag dbang blo bzang chos ldan gyi gsung 'bum (Beijing, n.d.; BDRC W1KG1321), vol. 2 (kha), 12b.2-3.

- 2For example, see Qing huidian shili (Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, Xinhua shudian, 1991), vol. 12, juan 1219, page 1118b.1-5.

- 3Naquin, Peking Temples, 342. Part of the temple's fame stemmed from the history and guidebook to the sandalwood Buddha written by the Third Changkya Lama, Rölpé Dorjé (Rol pa'i rdo rje, 1717-1786).

No part of Great Benevolence Temple is still extant. It was destroyed in 1900 by French forces during the suppression of the Boxer Movement.1Near the old site there is now a hotel, the Zhantan (or "Sandalwood") Courtyard Hotel (Zhantan jiudian 栴檀酒店), which offers a short history of the former temple on a wall mural in the alleyway leading to the hotel entrance (Figs. 10 and 11). Today the former grounds of the temple continue to host travelers, now coming not primarily from Tibet and Mongolia to see the sacred Buddha statue but from all over the world to experience the culture and cosmopolitanism of Beijing. Like the Great Benevolence Temple itself, significant portions of the culture and history people come to see and experience now exist only as a memory preserved in the use of the temple name. Temples that have survived have largely been repurposed or rebuilt to meet the needs of a contemporary social elite engaged in a different form of cosmopolitanism. Concurrently, the historical memories of these places have also been refashioned in light of present political and commercial contexts.

- 1Naquin, Peking Temples, 343.

Fig. 10 The entrance to the Zhantan Courtyard Hotel, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 11 Short history of the Great Benevolence Temple near the entrance to the Zhantan Courtyard Hotel, 2019. Photo by author.

While today there is not much left of the original structures of Protecting the Nation Temple or Great Benevolence Temple, there are other Tibetan Buddhist temples in the capital whose physical structures have fared better. In the remainder of this article, I will investigate the transformation of several of these temples, first looking at some which are now religious institutions, museums, and tourist destinations and then turning to others that have become commercial centers. These transformations have come in just the past several decades. At the same time that the urban landscape has been changed by economic development, there has been an increased interest in preserving historical structures and finding appropriate uses for them.

In a recent study of cultural heritage practices in China, Marina Svensson and Christina Maags trace this shift in attitudes toward “cultural heritage” (wenhua yichan 文化遗产) to the last decade of the twentieth century when the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) began to "search for a new form of legitimacy beyond communism."1This “heritage turn” has given a renewed sense of value to historical sites, but one that is often couched in a nationalistic discourse that promotes particular narratives of Chinese history as well as the role of the CCP in preserving China's cultural heritage. The approach of the CCP and the Chinese state toward cultural heritage can be understood as what Meyer and de Witte call the “heritagization of the sacred.” Through this process, the Chinese state minimizes the religious significance of the site, often through transforming it into a museum or tourist attraction. These uses, in the Chinese context, encourage a secular public to view these sites as objects of historical appreciation. They also allow these former temple sites to be reframed as emblems of a unitary Chinese identity.

- 1Marina Svensson and Christina Maags, "Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime: Ruptures, Governmentality, and Agency," in Marina Svensson and Christina Maags, eds., Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contestations (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018), 14.

The heritage turn, in conjunction with market reforms, has also allowed space for non-state actors to become involved in strategies for preserving and utilizing cultural heritage sites. A number of private companies, seeing commercial potential in former Tibetan Buddhist temples, have invested in renovating or reconstructing select aspects of these sites as part of larger shopping and arts centers. This has occurred at the same time that interest in Tibet has increased in popular media, stoking a "Tibet Fever" (Xizang re 西藏热) that often draws on stereotypes of Tibet as an exotic and mystical land.1These commercial developments may be characterized as what Meyer and de Witte term the “sacralization of heritage,” in that the commercial developers of these sites often seek to evoke the perceived spiritual or mystical character of temple sites as a way to set them apart and make them alluring to potential clientele. Similar to the process of heritagization of the sacred, this sacralization of heritage also becomes a way to shape identity formation. Especially with the reuse of Tibetan Buddhist sites as shopping, dining, and arts complexes, middle- and upper-class consumers are encouraged to fashion themselves within the refashioned cityscape, to imagine identities for themselves which weave together a sense of ancient cultural heritage, mystical spirituality, and contemporary global consumer culture.

- 1Fen Lin, "Moon Over the Eastern Mountain: Constructing the Han Chinese Imagination of Modern Tibet," Journal of Popular Culture, 51, no. 3 (2018): 674-692.

Religious Institutions, Museums, and Tourist Destinations

Several Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples now function as religious institutions, museums, or tourist destinations, and sometimes all three of these at once. The most famous Buddhist temple today in Beijing, Yonghegong, is a good example of a temple that retains some religious functions while mainly serving as a tourist destination. On any given day, one can see people offering incense and prayers around the grounds of the temple. While there is a small contingent of mostly Mongolian Buddhist monks in residence, they are often busy managing the flow of tourists. The temple requires the purchase of a ticket to enter and most of the visitors are tourists making their way through the well-known sites of the city. There are museum-style placards throughout the compound and one temple building is completely dedicated to a museum display. These elements demonstrate the heritagization of the sacred, reframing visitors’ interaction with the site as one of cultural heritage consumption accompanied by exhibits which project a certain national identity. We see this same heritagization process at work in other Beijing temples, especially the Yellow Temple.

The Yellow Temple (Huang si 黃寺) north of Andingmen (安定门, 'Stability Gate,' the site of a former city gate that is now a subway stop) was historically in the midst of agricultural fields outside of the walled city but is now very much part of urban Beijing between the second and third ring roads. The Yellow Temple (Fig. 12) dates to the early Qing dynasty. It was significantly expanded in order to serve as a residence for the Fifth Dalai Lama who traveled from Tibet to Beijing in the winter of 1652-53. The eastern section of the temple no longer exists—in its place are large apartment buildings and business towers—but a portion of the western section survives and today houses a small museum and the High-level Tibetan Buddhism College of China (中国藏语系高级佛学院), which opened in 1987 to train Tibetan Buddhist leaders, especially reincarnate lamas, in Buddhist studies as well as monastery management and political education.1

- 1The High-level Tibetan Buddhism College of China's (中国藏语系高级佛学院) website page "About Us" (关于我们), accessed Oct. 10, 2023, http://www.zyxgjfxy.cn/cn/site/201803/t20180309_5532409.html.

Fig. 12 Entrance to the Yellow Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

When I visited the Yellow Temple in 2019, I found a nicely renovated, quiet temple. The surviving section of the temple contains a large and impressive stupa (Fig. 13) in an Indo-Tibetan style. The stupa was built by the Qianlong emperor to house personal items of the Sixth Panchen Lama (1738-1780), who died while visiting Beijing from central Tibet in 1780.1An old stela on the temple grounds, erected by the Qianlong emperor, commemorates the birthday of the Sixth Panchen Lama that occurred during the Panchen's visit to the Qing capital. This stela has an inscription that is recorded in Chinese, Tibetan, Manchu, and Mongolian (Fig. 14). The inscription consists of wishes for the long life of the Panchen Lama and praises him for bringing the teachings of Tibetan Buddhism from Tibet and spreading them in Beijing.2The stela thus emphasizes the stature of the Panchen Lama and the contributions he made to promoting Tibetan Buddhism within China, and especially Beijing.3

- 1The Panchen Lamas are the second most revered lineage of reincarnating lamas in the Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism, after the Dalai Lamas.

- 2The Tibetan and Chinese text of this stela can be found in Chab 'gag rta mgrin, ed., Bod yig rdo ring zhib 'jug (Lha sa: Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, 2012), 457. The Tibetan text explicitly refers to the Panchen coming "from Tibet…to spread the Yellow Hat (i.e., Geluk school of Tibetan Buddhism) teachings" (bod nas… zhwa ser bstan pa dar), while the Chinese states that he "came from the west to propagate the Yellow Teachings" (西来,宣扬黄教).

- 3A similar emphasis is found on a stela commemorating the establishment of the Zhao Temple (Zhao miao 昭庙) in the hills to the west of Beijing, also built for the Panchen Lama's visit. In that stela's inscription it specifically delineates between Tibetans and Chinese, stating the hope that the Panchen Lama's activities will allow both Tibetan and Chinese people to all obtain fortune and benefit. Chab 'gag rta mgrin, ed., Bod yig rdo ring zhib 'jug, 454.

Fig. 13 Sixth Panchen Lama's memorial stupa at the Yellow Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 14 A 1780 stela with quadrilingual inscription (Chinese, Tibetan, Manchu, and Mongolian) at the Yellow Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

The temple grounds also have more recent dedicatory inscriptions and plaques. Several of these inscriptions inform visitors that the temple was renovated just in time for the Beijing Summer Olympics in August of 2008. Some of these signs are in Chinese (Fig. 15), while others are again multi-lingual, though now featuring English in addition to Chinese and Tibetan (Fig. 16). This addition of English signals the emergence of a new English-speaking demographic, a new readership of these texts—international visitors coming to Beijing to absorb aspects of its culture and heritage and to observe international sporting competitions.

Fig. 15 A plaque commemorating renovations of the Yellow Temple carried out from 2006 to 2008. Photo by author.

Fig. 16 A sign (right) in Chinese, English, and Tibetan with information on one of the structures within Yellow Temple which mentions its 2008 restoration. The plaque in Chinese (left) similarly commemorates the 2007-2008 rebuilding of the structure. Photo by author.

The museum portion of the Yellow Temple contains exhibit pieces, with accompanying Chinese narrative text, on topics such as the Panchen Lama, the Yellow Temple, the new High-level Tibetan Buddhism College of China, and claims of Tibetan Buddhism's longstanding integration into the motherland beginning in the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Overall, the exhibits emphasize a particular view of the relationship between Tibet and China as well as the positive preservation and promotion given to Tibetan Buddhism by the nation and the Communist Party. For example, an historical introduction to the temple (Fig. 17) notes that it was built for the Dalai Lama's visit in 1652 as a way to "honor the Fifth Dalai Lama's patriotic activities."1This historical summary quickly passes from the visits of the Fifth Dalai Lama and the Sixth Panchen Lama directly to the 1979 declaration by the Beijing municipal government that the Yellow Temple is "an important Beijing municipality cultural heritage protection site" and the 2001 designation of the temple's stupa as a "an important national cultural heritage protection site."2

The history of the temple, the exhibit summarizes, is like a stone stela on which is inscribed "the strong determination and sincere desire of all ethnicities to protect the integrity of the motherland and protect national unity."1Such a presentation seriously distorts Tibetan history to make it fit within the modern nationalist discourse of the PRC. Until being forcefully imposed in the twentieth century, for most Tibetans throughout history there was no "motherland" or "national unity" composed of multiple ethnic groups "to protect." Such concepts would not have made any sense in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. As Qing historian Evelyn S. Rawski has stated, "The Qing political model was not the nation-state; the goal of the government was not to create one national identity, but to permit diverse cultures to coexist within the loose framework of a personalistic empire."2Instead of evincing a universal desire to protect national unity, the history of the Yellow Temple in fact demonstrates the complex relationships between a number of political and cultural entities that were negotiating for power over the course of the seventeenth through twentieth centuries.

Fig. 17 An informational placard within the museum at the Yellow Temple which briefly summarizes the history of the temple. Photo by author.

Similar to the main exhibit space, another exhibit at the Yellow Temple emphasizes national unity in the context of speaking about Tibetan Buddhism. A side hall near the entrance to the temple contains a supplementary exhibit entitled "Patriotic Elder" (Aiguo laoren 爱国老人). This exhibit, with narrative text in Chinese and Tibetan, focuses on Sherap Gyatso (Tib. shes rab rgya mtsho ཤེས་རབ་རྒྱ་མཚོ, 1884-1968), a Tibetan Buddhist scholar from Amdo/Qinghai who was sympathetic to the communist movement and later held official posts in the People's Republic of China. The title of the exhibit is attributed to the fact that several early revolutionary leaders of the PRC—Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, and Xi Zhongxun—regarded Sherap Gyatso as a "patriotic elder."

The exhibit highlights Sherap Gyatso's work editing Tibetan Buddhist texts in Lhasa during the 1910s and 1920s and his later involvement with both the Nationalist and Communist governments. However, it avoids discussing the turbulent political environment in Lhasa during Sherap Gyatso's time there, such as the Thirteenth Dalai Lama's attempts to shore up Tibetan independence by building up the Tibetan military and reforming Tibetan educational and financial institutions. The Dalai Lama later stepped back from these reforms, in response both to conservative factions in the Tibetan government as well as to reports on the fate of Buddhism in Mongolia under communism. Sherap Gyatso seems to have been reform-minded, maybe even an early supporter of communism, which is probably why he was made to leave central Tibet after the Thirteenth Dalai Lama died and conservative factions began to hold most of the power in Tibet.1

- 1For details on the life of Sherap Gyatso, see Sonam Dorje, "Sherab Gyatso," Treasury of Lives, accessed June 15, 2023, http://treasuryoflives.org/biographies/view/Geshe-Sherab-Gyatso/4642, and Heather Stoddard, "The Long Life of rDo-sbis dGe-bšes Šes-rab rGya-mchos (1884-1968)," in Tibetan Studies: Proceedings of the 4th Seminar of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, ed. Helga Uebach and Jampa L. Panglung (Munich: Kommission für zentralasiatische Studien, 1988), 465-471.

The informational board at the entrance to the exhibit extols Sherap Gyatso as representative of "the vast majority of Tibetan Buddhist monks who support the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party and the socialist system, and who support the integrity of the motherland and national unity."1This, again, misrepresents the history of a period in which intense debates about Tibetan politics took place among Tibetans. Only briefly mentioned at the end of a long chronology of his life is the fact that Sherap Gyatso was removed from all his official posts in 1964 and subsequently faced "a variety of groundless accusations" through the end of his life. Moreover, left unmentioned is that when he died in 1968, it was from injuries sustained from being beaten by Red Guards. It would not be until 1982 that his reputation would be officially 'rehabilitated' and he would again be seen by the government in a favorable light.

- 1绝大多数藏传佛教增众是拥护中国共产党的领导和社会主义制度的,是拥护祖国统一,民族团结的。

Chinese law on cultural heritage specifically speaks to how cultural heritage can be used to promote a national cultural identity and protect national unity.1Svensson and Maag further note that cultural heritage can "be used as a tool of governance to control and manage tradition, cultural practices, and religion, and to steer people’s memories, sense of place, and identities in certain ways."2The exhibits at the Yellow Temple, which given the lack of English in the display texts seem to be oriented toward a domestic audience, provide a nationalistic perspective on the relationship of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism to China. They avoid directly addressing any of the debates, dissent, protests, and violence that have occurred in the process of integrating Tibetan areas into the PRC, instead opting to paint with broad strokes Tibetan Buddhists at all times as uncritical supporters of "national unity"—the Chinese term, minzu tuanjie (民族团结), can also be translated as "unity of ethnic groups"—and of the Communist Party's policies in Tibetan areas.3The writing and presentation of history is, of course, one of the ways in which debates about the nature and identity of a country are carried out.4These exhibits demonstrate an attempt to manage tradition and religion in a way that promotes an unnuanced patriotism oriented toward an uncritical understanding of Chinese history and national unity. These temple museums attempt to shape memory and identity by naturalizing the incorporation of Tibet into the PRC within a narrative that makes that incorporation seem inevitable and seamlessly in line with the natural progress of history.

- 1Svensson and Christina Maags, "Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime," 19, where they quote from a 2011 law on cultural heritage which states: "[t]he protection of ICH [that is, intangible cultural heritage]…is conductive to enhancing the Chinese national cultural identity, to safeguard national identity and national unity and to protect social harmony and sustainable development."

- 2Svensson and Christina Maags, "Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime," 20.

- 3On the term minzu tuanjie (民族团结), especially in its use in relation to ethnic minority groups in China, see Vradyn E. Bulag, The Mongols at China’s Edge: History and the Politics of National Unity (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2002), especially chapter one, "By Way of Introduction: Minzu Tuanjie and Its Discontents," 1-26.

- 4For example, debates over how to narrate and teach the history of the United States have been very contentious, represented by the different perspectives of The 1619 Project website (https://nyti.ms/37JLWkZ) and book (Nikole Hannah-Jones, et al., eds., The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story (New York: One World, 2021)), on the one hand, and The 1776 Report (2021) by the President’s Advisory 1776 Commission, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/The-Pre…, on the other.

Temples like the Yellow Temple and Yonghegong retain some religious functions while also serving as museums serving to shape a view of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism as integrally linked to the "motherland" for centuries. However, other temples have been transformed into museums that are less directly related to their previous status as Tibetan Buddhist temples. Let us turn now to two such Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples.

True Awakening Temple and Longevity Temple

True Awakening Temple (Zhenjue si 真觉寺, also known as Five Stupa Temple, Wuta si 五塔寺) and Longevity Temple (Wanshou si 万寿寺) sit just down the road from one another on Longevity Road, which takes its name from Longevity Temple. True Awakening Temple is now home to the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum (北京石刻艺术博物馆), and Longevity Temple now houses the Beijing Art Museum (北京艺术博物馆). The Beijing Art Museum was under renovation during my visit in 2019, but reopened in 2022. While today these two temples are within the hustle and bustle of urban Beijing, in the Qing period they were in the relatively uninhabited open space outside the western city wall. A late-nineteenth-century painting (Fig. 18) shows these two temples next to each other along the north bank of the Nanchang River (Nanchang he 南长河).1This painting was made after the rebuilding of the Summer Palace in the 1880s and shows a bird's eye-view of the Summer Palace and its environs, all to the northwest of the walled city of Beijing. In the painting, the Chinese layout of these temples is visible, consisting of a series of main halls along a north-south axis (south being at the left side of the painting and north at the right side).

- 1Beijing Summer Palace and Eight Banners Barracks (Beijing Yi he yuan he ba qi bing ying), painting c. late nineteenth century, digitized by the Library of Congress (Geography and Map Division, call no. G7824.B4A35 1888 .B4), http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.gmd/g7824b.ct002439. For a similar scene of the northwest suburbs from roughly the same time period, see Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, figure 12.5 (pp. 430-31).

Fig. 18 Detail of a circa late-nineteenth-century painting of the Beijing Summer Palace and Eight Banners barracks in which can be seen True Awakening Temple (with the white five-pagoda tower in the back of the compound) and Longevity Temple (to the west of Zhenjue Temple, or just above it in the painting). Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division.

True Awakening Temple was built during the Ming dynasty. The temple was most famous for a five-stupa tower, modeled on an Indian style, in the rear of the complex (the white structure seen in Fig. 18). It was an active Tibetan Buddhist temple during the Qing, and even the site of elaborate birthday celebrations for the Qianlong emperor's mother in 1751 and 1761.1By the early twentieth century, nothing remained of the temple except for the five stupas and the two Qianlong stelae on either side. Several portions of the temple have now been rebuilt to produce the temple in its present state.

- 1Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 344.

In 1986, the former courtyards of True Awakening Temple were transformed into a forest of stelae to create the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum (Fig. 19). Here, the past has been collected and speaks through silent stone, all in the shadow of the five-stupa tower (Fig. 20). The Stone Carvings Art Museum at True Awakening Temple has the sense of a graveyard, not least because of the presence of the stupa itself (a traditional Buddhist monument which in one sense serves as a reliquary mound), but also because of the presence of some stelae that did in fact commemorate ancestors or serve as tombstones. These include the stone stelae which marked the graves of two dozen Catholic (mostly Jesuit) missionaries in China active during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, such as the grave marker of François-Xavier Dentrecolles (1662-1741, Fig. 21). The museum also holds the tomb of the Manchu noble Fushou (富綬, 1643-1669, Fig. 22), the grandson of the second Qing ruler, Hong Taiji (1592-1643). The mixture of stelae and grave markers that now find a home at the True Awakening Temple act as a quiet but continuing reminder of the cosmopolitan character of Qing-era Beijing, in which previous generations of social and religious elites from various backgrounds rubbed shoulders.

Fig. 19 Entrance to the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum on the former grounds of True Awakening Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 20 Stelae on display at the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum with the five-stupa tower in the background, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 21 Stela which served as the gravestone of Jesuit priest François-Xavier Dentrecolles (1662-1741), with inscriptions in Latin and Chinese, on display at the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 22 Tomb of the Manchu noble Fushou (1643-1669) on display at the Beijing Stone Carvings Art Museum, 2019. Photo by author.

Upscale Shopping, Dining, and Cultural Centers

If some temples serve as spaces where the traces of a cosmopolitan collection of past social elites continue to be present, several temples have been transformed into spaces where contemporary social elites can meet and mingle. In the managed market economy of today's China, the preservation of cultural heritage is sometimes accomplished through private investment and development. Former Tibetan Buddhist temples have proven to be attractive sites for commercial ventures, from fine dining to art galleries. In contrast to the nationalistic messaging of the museums discussed above, these commercial developments often consciously exploit the popular mystique and exoticism of Tibetan Buddhism to draw in customers. In doing so, these sites help craft an alternative modern Chinese identity that sees itself as culturally and commercially sophisticated. However, both the developers and clientele of these sites often eschew any actual engagement with the history and religious traditions of these temples, and instead use the temples as mere mise en scènefor elite international commerce.1

- 1In this analysis, I am drawing on the work of Jamyang Norbu who has noted that in most popular media presentations of Tibet in the West “the country and the people come across merely as the mise en scène for the personal drama of white people.” Jamyang Norbu, “Behind the Lost Horizon: Demystifying Tibet,” in Imagining Tibet: Perceptions, Projections, and Fantasies, ed. Thierry Dodin and Heinz Räther (Boston, MA: Wisdom Publications, 2001), 374.

Lofty Aspiration Temple

The Lofty Aspiration Temple (Songzhu si 嵩祝寺) complex and Abundant Fortune Temple (Longfu si 隆福寺) serve as good examples of this type of repurposing of old Tibetan Buddhist spaces in modern Beijing. The Lofty Aspiration Temple was founded in 1711 in the midst of two previously existing Ming dynasty-era temples, the Wisdom Pearl Temple (Zhizhu si 智珠寺) and Profound Dharma Temple (Fayuan si 法渊寺). The resulting temple complex served as the Beijing residence of the Changkya Lamas (Tib. Lcang skya bla ma ལྕང་སྐྱ་བླ་མ, Chi. Zhangjia Lama 章家喇嘛), a lineage of reincarnating Tibetan Buddhist teachers who became prominent religious advisors to the Qing court. Lofty Aspiration Temple was well-known as a publisher of Buddhist books in Tibetan and Mongolian languages. The temple suffered some damage and looting during the Boxer Movement, but even into the 1920s it was a place to which visitors from far away, including Russians and Americans, went in search of Tibetan and Mongolian books.1With the advent of the Cultural Revolution, however, the temple's printing blocks were all destroyed.2During the early PRC the temple complex was converted to be used by several factories, and by the 1970s the Beijing Dongfeng TV Factory (东风电视机厂) had virtually taken over the former grounds of all three temples.3

- 1Boris Riftin, "Mongolian Translations of Old Chinese Novels and Stories: A Tentative Bibliographic Survey," in Literary Migrations: Traditional Chinese Fiction in Asia (17th-20th Centuries), ed. Claudine Salmon (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2013), 132.

- 2Huang Hao, Zai Beijing de Zangzu wenwu (Beijing: Minzu chubanshe, 1993), 23.

- 3Liu Tam, "The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple: Policies, Actors, Debates," in Chinese Heritage in the Making: Experiences, Negotiations and Contest, ed. Marina Svensson and Christina Maags (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2018), 252-253. Huang, Zai Beijing de Zangzu wenwu, 22, 24.

In 1984, the temples were officially designated as a protected heritage site by the Beijing Municipality and ownership was given to the Beijing Buddhist Association, though the TV factory continued to operate at the site until 1992. By the early 2000s, the temple complex was largely abandoned and in disrepair. Then, in 2007, a group of investors began renovating the former Wisdom Pearl Temple to serve as an upscale dining and art space which opened in 2011. The new development includes a boutique hotel and a French-cuisine restaurant, the Temple Restaurant Beijing. One of the signature art pieces within the renovated temple is an installation by the US artist James Turrell. The piece, titled Gathered Sky, consists of a bare room with a rectangular skylight in the ceiling. The room is open in the evening hours around the time of sunset. Viewers lie on cushions on the floor to gaze up at the sky, watching the sky change color with the setting of the sun as a lighting system changes the colors of the interior walls of the room and soft contemporary music plays. While probably not the intention of the artist, the installation could be seen as a gesture toward the skylights that are traditionally present in the assembly halls of Tibetan Buddhist monasteries.

However, the renovation of Wisdom Pearl Temple, including Gathered Sky, were influenced more by vague notions of Asian spirituality (such as peace, tranquility, and ancient wisdom) than any particulars of Tibetan Buddhist traditions. In a 2014 review of the new development, the trend-setting WSJ (Wall Street Journal) Magazine stated that it "attracts a mix of affluent expats, curious travelers and wealthy Chinese residents" and that "stripped of its bleak Communist facade, the near-ruined temple today has a new life, subtly blending Eastern spirituality with contemporary Western style."1Around the same time as Wisdom Pearl Temple was being renovated and developed, the former Lofty Aspiration Temple was transformed by a different company into a private club.2The posh new venues, aimed at an upper-class clientele, elicited some criticism from both the government and the general public as to the proper use of a former religious site and cultural heritage space.3Many thought these spaces would be best utilized as museums, as True Awakening Temple and Longevity Temple have been, but, according to a survey done by Mingxia Zhu in 2015, the vast majority of people who visited the new Wisdom Pearl Temple found it to be an acceptable use of the space.4

- 1Tony Perrottet, "A Beijing Temple Restored," WSJ Magazine (Jan 23, 2014), accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-beijing-temple-restored-1390412037.

- 2Jess Macy Yu, "Restaurant in Beijing Temple Rejects State Media Censure," New York Times (December 21, 2014), accessed April 20, 2023, https://archive.nytimes.com/sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/12/21/res…. Tam, "The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple," 253-256.

- 3Tam, "The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple," 257-260, and Yu, "Restaurant in Beijing Temple."

- 4Tam, "The Revitalization of Zhizhu Temple," 259-260, and the survey data reported on pages 266-268.

When I was there in 2019, I saw visitors strolling the grounds, passing through layers of the site's history. Diners enjoyed cuisine at the French restaurant that occupies renovated buildings originally constructed during the site's factory days (Fig. 23). Others made their way through the former temple grounds admiring new art installations (Fig. 24) and the restoration of the temple's remaining original temple buildings. Unlike the temples-turned-museums with exhibits curated in line with government narratives, these commercial developments do not display an overt heritagization that denudes the religious character of these sites in favor of nationalist sentiment. Instead they demonstrate a subtle sacralization of heritage, capitalizing on the spiritual associations of the site to create an atmosphere and lifestyle identity sought by well-to-do consumers.

Fig. 23 Diners, seen through the windows of the building to the left, in the Temple Restaurant Beijing on the former grounds of the Wisdom Pearl Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 24 An art installation on the former grounds of the Wisdom Pearl Temple, 2019. Photo by author.

Like the Lofty Aspiration Temple complex, Abundant Fortune Temple dates to the Ming dynasty, but was only converted to a dedicated Tibetan Buddhist temple in 1723, the first year of the Yongzheng emperor's reign in the Qing dynasty.1Along with Protecting the Nation Temple, Abundant Fortune Temple hosted a regular market fair several times a month from at least the mid-eighteenth century.2These markets, held on the temple grounds, attracted visitors from far and wide. The original temple suffered a fire in 1901, though a small contingent of Tibetan Buddhist monks continued to reside there afterward.3

- 1Zhang, et al., Zangzu wen hua zai Beijing, 155. During the Ming the temple had housed both Chinese and Tibetan Buddhist monks.

- 2Miller, Monasteries and Culture Change in Inner Mongolia, 78. Lai, "The Economic Significance of the Imperial Household Department," 10.

- 3Elaine Yau, "David Hockney in the House: Beijing Temple's Revival Starts with Art Museum – Shanghai Xintiandi Restorer Talks Us Through the Project," South China Morning Post (Oct 10, 2019), accessed April 20, 2023, https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/3032097/david-hockn…. Naquin, Peking: Temples and City Life, 75 n. 77.

In 1988, the original temple site became the location of a new nine-story commercial building, the Abundant Fortune Tower (Longfu dasha 隆福大厦). Abundant Fortune Tower was damaged by fire in 1993.1It was subsequently abandoned and by the early 2000s the surrounding area had become neglected.2Similar to Lofty Aspiration Temple, private investors eventually saw potential in the site, with its ties to imperial history and culture, and began to develop it as a commercial and cultural center in 2019. As the primary developer told the South China Morning Post in 2019, "For the Longfu Temple project, we don't want it to become a traditional shopping district. Culture should be the entry point. Visitors come to it for culture. Retail, dining (and other consumer) activities are supplementary."3

- 1Yau, "David Hockney in the House."

- 2Jianing Li, Longyun Ren, Tianhui Hu, and Fang Wang, “A City’s ‘Urban Crack’ at 4 A.m.: A Case Study of Morning Market Vendors in Beijing’s Longfu Temple Area,” Habitat International 71 (2018): 15. Li, et al., show that there was a thriving morning market for a couple decades right in front of Longfu Tower, but it was closed in 2016.

- 3Yau, "David Hockney in the House."

When I visited the Abundant Fortune Temple area in August of 2019, the newly reimagined cultural center was in the midst of construction. On the Baidu satellite map of the area (Fig. 25), it looked like the temple had been rebuilt, but arriving on the scene I could not initially find the reconstructed temple. I came to realize that a new version of the temple had been built on top of the renovated Abundant Fortune Tower (Fig. 26), as shown in an architectural rendering of the tower displayed in a large advertisement at the site (Fig. 27). While the rooftop temple mimics in great detail the facades of the previous temple buildings, the interiors of the temple halls are completely modern and contain lounge and conference spaces. Of course, as with many of these temples, the architecture of the temple buildings themselves was not distinctly Tibetan Buddhist. Instead, it was often the interiors—the characteristically Tibetan Buddhist paintings, statues, ritual furniture and implements, as well as the monastic populations' dress and ritual practice—that shaped and conveyed these temples' Tibetan Buddhist character. It is just these interior elements that have been least preserved. What has replaced the Tibetan Buddhist artwork and furnishings gives clear indications of the new intended clientele of these temple spaces: a growing domestic and international urban professional class.

During my visit to Abundant Fortune Tower in 2019, I had tea and perused books at the stylish More Reading Book Club (Geng du shu she 更读书社) bookstore where one could find popular Chinese novels like To Live (活着, by Yu Hua 余华) alongside Chinese translations of the Harry Potter series and Dale Carnegie's How to Win Friends and Influence People. Large ads covering the fencing around the construction areas prominently referred to the new complex as "Abundant Fortune Temple" (Longfu si) and gave visitors an idea of the other commercial tenants that would be anchoring the space, including Burton, a US-based snowboard and outdoor apparel retailer; %Arabica, a Japanese coffee chain; and local Beijing microbrewery chain Jing A (Fig. 28). Probably the most publicized development, however, was the creation of a second location for the M Woods Art Museum, a privately-owned museum whose first location was established in 2014 in the popular 798 art district on the northeastern outskirts of Beijing. The M Woods Art Museum has gained a strong reputation as a quality museum for contemporary art in Beijing. The opening exhibit at the new M Woods location at Abundant Fortune Temple was of work by the British artist David Hockney, one of the world's most successful contemporary artists. The exhibit featured one of Hockney’s most famous works, A Bigger Splash, in which a splash of water rises out of a backyard pool. A yellow diving board sits in the bottom corner of the canvas while a pair of palm trees rise tall and slender in the background. There was even a rooftop recreation of the scene of A Bigger Splash, featuring yellow diving boards next to a fake palm tree. In an area where Tibetan Buddhist paintings of buddhas and bodhisattvas were once displayed, there was now a presentation of bright, pop art paintings of California pool scenes.

Fig. 25 Screenshot from Baidu Maps, March 18, 2022, showing the new temple buildings that are on the roof of Abundant Fortune Tower.

Fig. 26 View, from the ground, of the top of Abundant Fortune Tower with the new temple buildings on the roof, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 27 An architectural rendering of Abundant Fortune Tower and surrounding buildings displayed in a large advertisement at the site, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 28 Large ads covering the fencing around a construction area of the Abundant Fortune Temple complex displaying the commercial tenants that would be anchoring the space, 2019. Photo by author.

As indicated in the statement from the developer quoted above, the new cultural and commercial center hoped to draw in an elite clientele through the associations of the site with Beijing's cultural history coupled with the allure of international—especially contemporary Western—retail, art, and culture. Large signs in the Abundant Fortune Templearea introducing the new complex explicitly crafted this sense of identity for the space and those who chose to frequent it. The Chinese text on these signs read: "Abundant Fortune Temple combines together ancient and modern Abundant Fortune, the openness of the capital, an international landmark, and culture," while the English text read, "Blending of Eastern and Western Cultures."1The text was reinforced by images which contrasted a statue of Confucius with Socrates (Fig. 29) and images of a Chinese opera performer with a violin (Fig. 30). Spanning the bottom of each sign was an image of a temple roof, acting as a bridge between the two iconic representations of "eastern" and "western." Tibetan Buddhist temple sites such as that of Abundant Fortune Temple have thus been reclaimed in the last two decades as elite cultural spaces that combine old and new, traditional and modern, the high culture of the past and present, East and West. These sites become signifiers for the identities of those who come to be in and patronize these spaces.2The temple space—as a physical site, as material trace, as a remembered past, or even just a name—becomes an important element in the rhetorical creation of global cosmopolitan spaces in China's modern capital that in turn inscribe the people passing through them. However, actual Tibetan Buddhist history and culture are not a part of this new cosmopolitanism. It is instead dominated by Western and Han Chinese culture, with little room for other cultures and voices.

- 1隆福寺: 古今隆福 + 开放首都 + 国际地标 + 文化四合

- 2Such conceptions of identity as the blending of the best aspects of Western and Chinese culture have a long pedigree, as seen for instance in the short story "A Happy Family" (幸福的家庭), written in 1924 by the writer Lu Xun (鲁迅)—considered to be one of the founders of modern Chinese literature. An English translation of that story is contained in Lu Xun, Wandering (Beijing, Foreign Language Press, 1981), 32-40. The couple in the story are described as "the cultured élite, devoted to the arts." They speak English. They eat Chinese food because "Westerners say Chinese cooking is the most progressive, the best to eat, the most hygenic." In the husband's study, "the shelves are lined with Chinese books and foreign books."

Fig. 29 Large sign in the Abundant Fortune Temple area introducing the new complex, 2019. Photo by author.

Fig. 30 Large sign in the Abundant Fortune Temple area introducing the new complex, 2019. Photo by author.

Conclusion

Beijing's Tibetan Buddhist temples have always been places through which diverse groups of people moved. During the Qing, these were spaces where elites from different backgrounds met, collaborated, and enacted the multicultural character of the empire within the capital. The temples themselves announced the pluralistic nature of the Qing dynasty, as well as its grandeur, through their public display of signs and stelae aimed at the multi-ethnic audiences of the empire.

During the Qing, the establishment of Tibetan Buddhist temples in the city was both an attempt to transform Beijing into an Inner Asian capital and also a way to co-opt Inner Asian cultures for political purposes. The Qing emperors and much of their court were ethnically Manchu and they identified themselves as distinct from Han Chinese and culturally closer to other peoples of Inner Asia. This aspect of their identity meant that they were intent not only on creating—often through military force—an empire that included vast stretches of Inner Asia, but that they also wished this new empire to be not just another Chinese dynasty. Instead, they imagined a polity with an altogether different character, one that embraced and encouraged a diversity of cultures and patronized the implantation of elements of those cultures within Beijing.1

- 1The sentiments in this paragraph are influenced by the scholarship identified as "new Qing history," for which see note 4 above. Ruth W. Dunnell and James A. Millward, "Introduction," 5-8, demonstrate that similar public displays were constructed during the Qing at the summer resort at Rehe (today's Chengde).

Today, however, the remaining vestiges of Beijing's Inner Asian culture and religious sites, including Tibetan Buddhist temples, are being transformed by two distinct modes of engagement with cultural heritage: the heritagization of the sacred and the sacralization of heritage. After a period of hostility toward religious cultural heritage, the government of China now officially promotes certain forms of heritagization. Surviving structural elements of some Tibetan Buddhist temple sites in Beijing are now being preserved or renovated. But as Meyer and de Witte note, “In the making of heritage, the appropriation of religious and cultural forms by the state into a new, national frame impacts these forms and their evocative power.”1In transforming these sites into museums and tourist attractions, the “evocative power” of these places has been harnessed to promote a vision of nationally unity both historically and in the present.

- 1Meyer and de Witte, “Heritage and the Sacred,” 278.

The second mode of engagement is seen in commercial development of former Tibetan Buddhist temples into sites of Chinese and global culture and commerce. These spaces today are meant to speak to sophisticated urban consumers (often Han Chinese) looking to create lifestyle identities that pair modern, upscale, international brands with an appreciation, or the appearance of appreciation, for China's historical religions, cultures, and arts. As Svensson and Maags note, the development of heritage sites "often privilege elites and the middle class in their cultural and leisure activities."1We can add that these spaces also privilege the interests of dominant groups, including dominant ethnic groups in China. While these spaces might appear to promote cultural diversity and inclusion, they more often provide opportunities for members of the dominant culture (Han Chinese) to create their own meaning for these spaces which augment and add value to their own identities and cultural positionality, and do very little for the mixture of cultures (Tibetan, Mongolian, Monguor, Manchu) from which these temples originally emerged. On the contrary, the attempt to re-sacralize these heritage spaces for commercial gain often ends up either perpetuating stereotypes or distorting history.

- 1Svensson and Christina Maags, "Mapping the Chinese Heritage Regime," 15.

As scholar Fen Lin has noted, Han Chinese perceptions of Tibetans and other ethnic minorities have often fluctuated "between otherness and belongingness."1Sometimes Tibetans are cast as exotic and spiritual "others." At other times, often due to the nation-building policies of the government since the reform era, Tibetans are represented as historically integral to a unified Chinese people. Both of these conceptions of Tibetans and Tibetan Buddhism are on display at Beijing Tibetan Buddhist temples today. As commercial spaces, they capitalize on popular notions (in both China and the West) of Tibetan Buddhism as mysterious and mystical in order to create an alluring atmosphere. Especially as museums, these temples promote a particular version of history, transforming the collective memory of these sites into one compatible with the historical narrative promoted by the government of the People's Republic of China. If we think of Beijing as a palimpsest, the original Tibetan Buddhist elements inscribed onto the landscape of Beijing have been both etched out and also covered over by these recent processes of heritagization. The new narratives written over the landscape of Beijing, while making gestures toward the history of these sites, primarily advance the interests of the state, of commerce, and of contemporary urban cosmopolitans. Traces from underlying layers remain, however, and if we examine these closely they offer us the opportunity to read the changing landscape of Beijing and the shifting meanings of its Tibetan Buddhist temples.

- 1Fen, "Moon Over the Eastern Mountain," 684.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.2232/mav.ess.2025.1

1. Benjamin J. Nourse, "In Search of Beijing’s Tibetan Buddhist Past and Present: Religious Heritage, History, and Identity in Modern Beijing," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 9, no. 1 (2025), doi: 10.2232/mav.ess.2025.1.

Nourse, Benjamin J. "In Search of Beijing’s Tibetan Buddhist Past and Present: Religious Heritage, History, and Identity in Modern Beijing." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 9, no. 1 (2025), doi: 10.2232/mav.ess.2025.1.