Judith Ellen Brunton is a scholar of religious studies and the environmental humanities. She is currently a William Lyon Mackenzie King Postdoctoral Fellow at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University. Her doctoral work took an ethnographic and archival approach to explore how legacies of oil extraction allow for contemporary imaginaries of the good life in Alberta. Judith is broadly interested in questions of land and labor, secularity and enchantment, religion-making, and method, in the North American West.

The following exchange took place over the autumn months of 2020 between Judith Brunton, Chip Callahan, and Alex Kaloyanides. After reading each other’s original offerings to the Characterizing Material Economies of Religion in the Americas project we endeavored to find resonances and important questions our triad posed. We each emailed one letter to the others, first Judith, then Chip, then Alex. These letters offer moments of speculation on the religions and resources shaping our research objects and on the supernatural powers and economies they enchant.

Judith. Sept 14 2020.

When the Characterizing Material Economies of Religion in the Americas group met this past summer, the conversation dwelled for a moment on the question of religion attempting to manage and define resources. Our colleagues brought up questions like: what is being constructed as a resource and how? What resources does a person need or not need? What is the resource for? Both Alex’s eBay Buddha and Chip’s sperm whale teeth add andto this discussion. Material economies of religion in the Americas in these texts are characterized by the imagining, transformation, and movement of resources. Both texts provide an opportunity to think about resources as central to material economies of religion in America, without limiting resources to their materiality. Resources, in these texts, are not only (or necessarily) material. That is just one part of the network of meaning at work in the construction of a resource. Each text suggests possibilities for how to think about the context of significations, practices, and narratives that create a resource, how religion organizes these, and how the material thing in question may be acting in these relationships.

Alex’s text helpfully presents the moment of sale of a golden Buddha on eBay to imagine this artifact as the economic legacy of teak in Burma. This Buddha and teak speak to an economic system in which values of exclusivity, authenticity, and desire organize religion (and/or are organized by religion?). The eBay Buddha is very similar to the Burmese Buddha in the British Museum which was made from teak in a context within which teak “took on a special religious and economic status” because of the relationship between King Mindon and British colonial forces. Alex explains that King Mindon wanted to arm his palace guard with guns to avoid a coup, so he threatened to stop selling the British teak “arguing that it was a special kind of Buddhist wood he had a right to reserve for Buddhist statues and buildings.” This argument was compelling to the British who had a “romantic attitude” towards both Burmese forests and Buddhism, both of which they saw themselves as appropriate caretakers for. There seems to be a query posing behind Alex’s description here: is teak not a special kind of Buddhist wood because King Mindon’s description was motivated by a desire to purchase guns? Alex seems to suggest that no, the process of bringing teak into the British economy and economy of values this way made teak a special kind of Buddhist wood. Because of the British desire to understand forests and Buddhism within the same romantic narrative and because of a Buddhist King’s desire to buy guns, both the weapons themselves and the negotiation for them are made especially Buddhist as well.

Buddhism organizes here, but not from a formed position before the fact. There seems to be a couple different Buddhisms doing different work to create this economy and to eventually create the eBay Buddha moment, and in doing so create themselves. Alex states: “The material of teak, the economies of the British and Burmese empires, the religion then being named ‘Buddhism,’ now give us this American eBay Buddha.” Specifically, it seems, these empires and the British anxiety about exclusivity and authenticity shape the kinds of rituals appropriate for imagining Buddhism and teak. King Mindon ‘threatened’ to stop selling the British teak, but I imagine if this gun sale went through that Mindon did continue to sell them teak. This makes me wonder more about the British narrative of themselves buying this special Buddhist wood. That they were the right people to buy it? That Mindon was the right person to sell it? This line of questioning, as Alex frames, sets us up to ask questions of the potential eBay purchaser. How is this idea of authenticity created through the act of buying and selling? How does capitalism become the caretaker? Is the eBay moment another ritual to assess and assign appropriate value to the Buddha? Through showing the kinship between the eBay Buddha and the Buddha in the British Museum, Alex also frames the possibility of other kinships, like how the purchase of the eBay Buddha may replicate the British desire to protect Buddhism through acquisition.

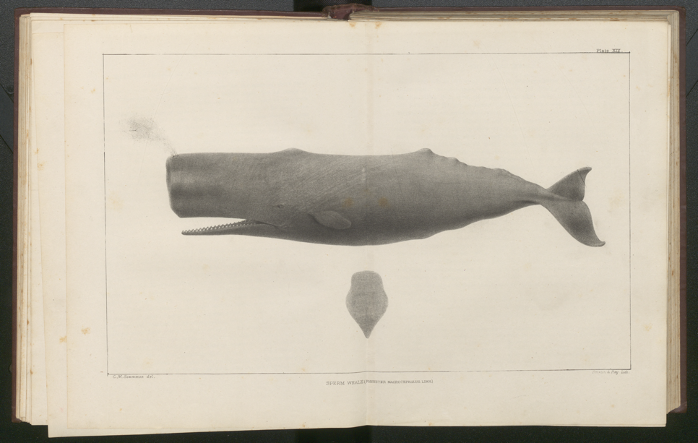

Chip’s text describes a quartet of moments in which sperm whale teeth are circulating materially and/or symbolically in different economies. Each of these cases are constitutive, both presenting a different context for the teeth’s circulation and how religion might be organizing it, and providing an opportunity to imagine how these are not different cases but are instead one big case. The teeth seem to demand both approaches. In two of the cases the whale teeth can be called Tabua as they are in a Fijian context. In the other two contexts the teeth are circulating in North American contexts. Chip’s description of these contexts both frame their difference but also pose the materiality of the teeth as common amongst some of them. I could picture the whale itself swimming to the different locations to lend its teeth to these different systems. The American whaling industry, and the process of industrial whaling overall, is also common among some of these contexts. It follows the material whale wherever it goes.

These case studies, both as independent moments and as connected instances, suggest that sperm whale teeth are the kind of thing that have their meanings translated by practices of consumption and access. Religion is organized and organizes here through consumption. The teeth are transformed by consumption on different occasions into ceremonial objects, waste, museum artifacts, symbols of access, and symbols of critique. Chip speaks to how the availability of whale teeth “widened tabua ceremonial exchange networks to include deal-making with American and European traffickers in sandalwood and beche-de-mer. Availability also shapes how the teeth are imagined and used in the American whaling context, where easy access allows them to be transformed into scrimshaw by whaling men. The consumption of the teeth then shifts from widening consumption to more rarefied use, as the scrimshaw is museumified and the tabua resonates symbolically in the airline card as exclusivity. Courtney M. Leonard also speaks to this limitation in their artistic critique. In each of these contexts the consumption of the teeth also play a role in organizing religion into Fijian ceremonial contexts, labor structures, corporate imaginaries, and de-colonial art. Leonard’s art highlights how questions of consumption are also questions of access: who can participate in these various teeth economies. A question that becomes more about all of these contexts as the whaling industry and other factors have impacted the material whale itself. This material reality seems to culminate in the airline’s card, where there is no material tabua in question, only its symbolic power (I am reminded of how often credit cards have a level called a “Gold Card”). The card seems both to require the material conditions that made the tabua important within certain economies, but also that made it so rare as to make access to something called a tabua club exclusive. In all the cases Chip presents, the flow of access maps the ceremonial and economic value of the tooth.

These questions of access and consumption allow for these cases to be put in conversation in interesting ways. For example, I wonder how the ceremonial use of the tabua in Fiji, that of the people of the Shinnecock Indian Nation, and of 19th century whaling men are in relation. What can we learn from the different methods of getting the teeth: hunting vs. harvesting? I also wonder what we would learn from death’s prominence in these economies. Does the language of relics allow us to follow the reality that these economies require the whale’s death? Are these different economies also different understandings of this creature’s death? Death generally?

This brings me to one of the questions that I think could be asked of both texts. If we are thinking about ‘resources’ and the way they are managed by religion as a way to think about material economies of religion, what can we learn from these texts where resources are material parts of the natural world and require extraction? Is it possible that it isn’t the materiality, or the economies, or the religion of “material economies of religion in the Americas” that bring these natural materials and their extraction to the fore, but the “in the Americas” part? I don’t want to obscure the uniqueness of these cases by gesturing to global forces like imperialism, but instead suggest they are non-global articulations of global forces. Anna Tsing’s (2005) description of friction may be helpful here, practical encounters as a way to do an ethnography of the global. Or maybe Lisa Lowe’s framing of “intimacies” in her The Intimacies of Four Continents, connecting the realities of ‘new world’ economies and the development of modern liberalism?

The texts bring up another question for me, but humor me because I don’t entirely know how to describe this feeling, but in both of your texts the materials in question do seem universally valuable to me. Trees and whales seem like very old gods, deserving of our respect. Is it possible that the processes you describe translate their value into other value? Do their participation in these economies of value represent their attempts to speak their value into different worlds? If so, what does it mean that to translate their powers into new worlds these old gods use the categories of access, desire, and transformation? Are these possibly essential categories of religion and economy for colonial networks? What relationship do ‘resources’ have to these seemingly old gods and their value? Or maybe I am just falling into the same trap the British did, with their romance of forests.

Chip. Oct 30 2020.

Judith,

First, thank you so much for such a thoughtful and provocative overview and analysis of Alex’s and my submissions. This was very helpful to read, and is pushing my thinking in productive ways.

I love how you begin by situating our pieces in the context of thinking about resources. During our initial Zoom salon I was a bit resistant to the idea that “religions manage resources” because that view didn’t seem to me to attend to the ways that resources make religions, and create the material conditions for the possibilities of various religious practices, positions, and orientations. When I read about material culture, or religion and materiality, especially over the past decade or so (it seems), I often find myself reading about the objects of religion—from paintings and architecture and sculptures and clothing and food to ritual items, artifacts, books, and that sort of thing. This is fascinating stuff, and there is wonderful work being done on the objects of religious practice. But behind all of these things—and something that I think all three of our pieces really draw out—lie natural resources. That is, the basic non-human materials out of which religion and culture are made (and therefore, I might add, out of which various meanings of the human are made). These basic material resources and their extraction from where they initially lie is not always what we look at when we think about religion—unless we are working in environmental ethics or something. But perhaps thinking about “material economies of religion” helps us to look more thoroughly into the full economy, and ecology, of material making—and of religion making. Or maybe not; maybe we just got lucky with these three pieces, and your initial reflection on them, to point us in that direction.

I think about this relationship between religion and material resources as a dialectic: religion orients individuals and communities to certain relationships to and conceptions of matter, and embodies those relationships and conceptions through practices that further legitimate them, making them appear “natural.” But particular material resources are required for the production and maintenance of that way of being in the world, as well, shaping the ways that that orientation is experienced and expressed. The labors of natural resource extraction, of gathering and transforming raw materials into “culture” or “civilization” or an inhabited world, impact, shape, produce, and limit religious ideas, practices, and imaginations. I’ve written about this in terms of “taking up and making something of things.” And in some sense, I think this is part of the process of a “material economy,” the circulation of material objects across borders and boundaries, across domains of value, and between materiality and meaning/conception/idea.

Judith and Alex, both of your artifacts, if viewed through this lens, illuminate different aspects and points in the dialectic. Alex’s story of the gold and teak Buddhas shows how the material setting of international trade across cultural and economic borders in particular circumstances produces teak as a religious value (for different but related purposes on each “side” of the circuit). Judith’s oilpatch workers have Christianity underwriting oil extraction, and the work of oil (and its basic foundation in modern life) shaping Christian interpretation/practice towards giving oil a Christian value.

Judith’s oilpatch workers illustrate, and illuminate, the movement between the necessity of oil for the production of a particular form of modern “civilization,” one the one hand, and a conception of how the work of extracting that particular material necessity produces, or requires, a particular way of being human. God’s Word for the Oil Patch, Judith writes, “theorize[s] both the value of energy and the kinds of lives people need to live to access this value.” And in this theorizing, oil and Christianity merge, the materiality and labor of oil extraction providing metaphor, symbol, and image for a retold Christian narrative, which in turn gives particular meaning and value to oil, spiritualizing the energy it contains and produces. One question I have for Judith: you call this book a “bible,” but don’t really explain why. Is this a term the oilpatch workers or executives would use? Is this your own rhetoric? What is the material economy of this discourse, taking this book and applying the name “bible” to it, making it appear as (or at least bringing it in comparison with, or allegorically or metaphorically connected to) the Christian sacred text? Is this your move to bring a “religious value” to this text, to get your reader to see it that way, or is this something you’re seeing in the Fellowship’s conception and handling of it? In other words, is the value created here one that YOU are creating, or one that others are creating and you are observing? Or are you trying to draw out explicitly a value that you feel they are producing implicitly?

Alex’s Buddhas—one gold, one teak—pull in a different (but related) direction: here a basic natural resource gains both an economic value and a religious one through its circulation across borders of national interests in an international (global?) economy. Like oil, teak’s value was produced through both its perceived need for “civilization” as constructed and lived in the late nineteenth century (as a necessity for shipbuilding, on the part of the British, and as leverage against colonial power, on the part of the Burmese), and its circulation through a discourse on religion and religious imagination. It is fascinating to me that teak gained a religious value—apparently “made up” by the Burmese, but nevertheless accepted as a religious value by the British—through the very particular material conditions of the relationship between the nodes in this network of circulation (colonialism, British shipbuilding, European romanticism, theories about religious development, firearm access, etc.). I’m also fascinated by how the teak Buddha resembling the British Museum piece ends up being reproduced in gold and available on eBay—now made of a material that itself signifies certain types of value that have little to do with the value produced in the specific relationship between Buddhism and teak and Burma and Britain at the time of the teak Buddha’s origin. What does this materiality, the actual material out of which each Buddha is constructed, do to each respective Buddha’s value (economic, spiritual, historical, symbolic, whatever)? What is the significance of a value that is created in a particular colonial setting being re-presented as a value created in and for a capitalist market of collectors? Finally, I am wondering about the American part of the “material economies of religion in the Americas.” Is it eBay? Does eBay’s “virtual” location put “the Americas” everywhere, in this age of global capital?

I haven’t yet addressed the really interesting issues of access that Judith raised in her message. I’m still thinking about those points, and I think there’s a lot there. My mind keeps coming back to the ways that religions manage access, in one way or another, to “natural resources,” in a variety of ways: in terms of rituals and protocols concerning literal access; in terms of the imagining the possibility, necessity, or desirability of accessing particular resources; and in terms of how material resources produce the conditions through which religious power can be accessed and mobilized. I look forward to thinking further about this, and trying to find ways to articulate those thoughts across this variety of settings that we have before us in Judith’s, Alex’s, and my own projects. But I do want to briefly note that Judith’s closing questions in her writeup seem to me to be very relevant in all of this—your questions bring to mind both “new materialism” and theoretical/methodological perspectives on “spectralities” and “hauntology.” And this, to me, brings us directly into a realm of religious studies that I think is underexamined but really potentially robust: the ways that materiality has agency, produces surpluses that impact us in “spectral” ways, create forces and powers that humans experience as “supernatural” or spiritual, etc. When it comes to the basic, fundamental “natural resources” out of which the “human” world is built, through which human (and non-human) beings know, experience, and exist in the world, these material resources literally are essential, and the gathering, extraction, exchange, and work of transforming them set up basic relations to matter and the possibilities and limits of what it means to exist. I don’t think this is just romanticism. I think that looking here, or at least including this issue, might be very productive for thinking through material economies of religion.

Alex. December 10 2020.

Dear Judith and Chip,

It was so lovely to see both of your faces today at the American Academy of Religion’s Zoom session “Thinking American Futures.” The inspiring case Chip’s made on the panel for the Blue Humanities has me returning to our correspondence about our MERA project. I so appreciate the smart and creative ways both of your earlier emails explore the relationship between religion and resources. Your writings had me listening keenly to how Chip talked about the way that raw materials are extracted in order to create the joys of civilization. In Chip’s case of whaling in the Atlantic, whales are hunted and processed in order to create the material conditions of Christian New England and beyond. In Judith’s work, the extraction of oil creates the material conditions for the “good life” that the Oilfield Christian Fellowship’s God’s Word for the Oil Patch narrates. And in my research into the teak industry, the tropical hardwood is extracted to enable both the empowerment of the seafaring British Empire as well as the claim to the Burmese kingdom’s continued independence.

Thinking about oil, whales, and teak together has me excitedly imagining future religious studies collectives investigating natural resources and the way they are transformed into religious lives. Judith writes about how the Oilfield Christian Fellowship describes a power moving “through oil and the kind of energy produced by it.” Chip describes “nature being turned into culture” It’s something like a hip, yet nerdy, twist on the Animal, Vegetable, Mineral? game. We pick a particular thing from the natural world and then study how it becomes a part of a religious world (and how that religious world then becomes naturalized).

What seems meaningful (righteous?) about this way of designing projects is that it makes us all think more about both the treatment of the environment and the labor that goes into the extraction of these resources. In all of our projects there is a kind of melancholic recognition that burning fossil fuels, overfishing, and felling forests has done irreversible damage to this planet and all who live on it. The massive economic power of all of these industries also presses us to consider the workers in these industries who are given little in return for their labor, all while the heads of these companies grow extremely wealthy. I can see how both of your projects will bring a greater awareness to ecological dangers and economic exploitation and even create opportunities for political action.

Given all of our training as religious studies scholars, I have been wondering what we are positioned to do with these studies that scholars in adjacent fields are not. Being in conversation with you has me thinking that our projects have something revelatory to say about the practices that turn these resources into what you two have been calling “culture,” “civilization,” and “the good life.” It strikes me that in contrast to the gloom and doom of my previous paragraph, these terms have a sunnier complexion. Maybe the religious part of these stories is in the alchemy of turning oil into gold, whale teeth into fine art, teak into buddhas. Chip’s presentation today recreated an image of the joys of civilization in the nineteenth-century U.S. that were dependent on manufactured things like soap and corsets. I wrote down Chip saying something like “products and labors of the sea were requirements for the possibility of Christianity as imagined.” How does this nineteenth-cenuty practice of imagining relate to the messaging of Calgary’s “Be Part of the Energy” campaign and the narrative work of God’s Word for the Oil Patch? How do we explain and analyze the way that tangible things become incorporated into abstract concepts?

Judith begins to answer this question through a kind of rhetorical analysis of how Olifield Christian Fellowship's “bible” presents oil and gas as both dangerous and rewarding. I wonder how much the mechanics of oil drilling and the related perilous labor practices invigorate the sense of a good life that members of the Calgary Petroleum Club enjoy. Is there a friction there that requires scripture, ritual, and God to smooth over? And Chip’s turn toward the overlooked depths of the ocean suggest that whale teeth for communities in Fiji, nineteenth-century America, and the Shinnecock Nation were extracted to provide a physical connection to fathomless immaterial power. Are these practices by which, to borrow Chip's words, the various meanings of the human are made? Are they how gods are manufactured?

I’ll end there, but not before I thank you both for this exchange. I look forward to learning more from you about the extraction of religion.

This conversation relates to Alexandra Kaloyanides’s study into the eBay Buddha, Judith Ellen Brunton’s examination of Oilfield Christian Fellowship’s theology, and Richard (Chip) J Callahan, Jr.'s research into the circulation of sperm whale teeth.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.convo.2022.3

1. Judith Brunton, Richard Callahan, and Alex Kaloyanides, "The Old Gods: Whales, Oil, and Teak," Conversation, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.convo.2022.3.

Brunton, Judith, Richard Callahan, and Alex Kaloyanides. "The Old Gods: Whales, Oil, and Teak." Conversation. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.convo.2022.3.