Laura Levitt is Professor of Religion, Jewish Studies, and Gender at Temple University. She is the author The Objects that Remain (2020); American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (2007); and Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home (1997) and a co-editor of Impossible Images: Contemporary Art After the Holocaust (2003) and Judaism Since Gender (1997). She is currently writing about the offerings left at The Tree of Life Synagogue and at George Floyd Square while working on a book about the former East German writer Christa Wolf. https://lauralevitt.org/

Authors’ note: We three have corresponded on multiple occasions over the course of three months (September, October, and November of 2020), by Zoom and email. This correspondence has been generative for each of us in different ways. In Sally's and David's cases, it has led to the inclusion of new material and new lines of inquiry in current book projects.1 In Laura’s case it has produced new reflections on recently published work: a monograph, and two MAVCOR Journal pieces (here and here) that were composed also as part of MAVCOR’s current project cycle on Material Economies of Religion in America (MERA).2 What follows is a collaboratively written exercise that points to various connections across our subjects as well as the important ways our thinking has been shaped by our conversations to date. If Laura’s voice is perhaps less obvious, it is because her related book project is complete, available now in its entirety. It is also because her 2000-character piece for this project is itself about a kind of brevity, about sparse prose and what is left unsaid, an insistence on not articulating too much, on pushing back against cultural hyperbole. Her concision echoes and honors Maggie Nelson and Jane Mixer in ways Nelson wants Mixer to be remembered. All that follows is nonetheless dependent on Laura’s active participation in this conversation, as wise contributor and choral director to collaboration—first out of the gate to put ideas on paper after initial discussion. We three refined our work together at precisely the time that Laura’s book launched and when Joe Biden won the United States presidency, a small spark of light in the American catastrophe of racialized violence that had been 2020. We offer these words, in this moment, as deliberately political scholarship.

- 1Sally M. Promey, Religion in Plain View: Material Establishment and the Public Aesthetics of American Display, under contract with University of Chicago Press, 2023 projected publication date. David Walker’s book project is tentatively titled Mormon Wrestling: A Genealogy.

- 2Laura Levitt, The Objects that Remain (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2020); Laura S. Levitt, “Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect,” Object Narrative, in MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018); Laura S. Levitt, “Revisiting the Property Room: A Humanist Perspective on Doing Justice and Telling Stories,” Mediation, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015).

In considering commonalities across the 2000-character pieces we separately produced for the initial 2019 AAR #CaptioningReligion conference panel and this salon, we were struck first by the fact that we are all concerned with bodies in various states or stages of visceral excess—bloody death, bare skin, bedazzled clothing, obsessive iteration, outright gigantism—and the affects and conditions of their circulation before different viewing publics. For all three of us, embodied sense perceptions and affects are materially significant. They have consequences for the ways people make decisions and for ways of inhabiting and comprehending the world. Despite Protestant secularity’s claims to the contrary, sensation and affect are no more confined to interiorized subjective mental states than is religion merely belief. Affect figures importantly in acculturation, in making things appear benign and familiar, in standardization (in the repetitive standardizing labor of sentiment). All of our subjects, moreover, are invested in controlling somehow the narratives that accompany the circulation of bodies, objects, and images and thus also inform those circulating views. And finally, all of this work—concern, embodiment, circulation, observation, narrative, publicity, and public-formation—can be seen to constitute both an economy and an archive of genealogical relations—and thus also religion. We begin these reflections with some thoughts on economies and genealogies.

Economies and Genealogies

Given the terms of our larger collaboration (Material Economies of Religion in the Americas), the salon convened under this rubric by Kati Curts and Alex Kaloyanides (in person at AAR 2019 and virtually in the midst of pandemic) has made space to think more deeply about the meanings of economy itself as we deploy them. Among the three of us, we have trained our attention on various possibilities of the word, important among them: the sustenance and sustainability of certain vocations (David); the use-value of strategic diversity (Sally and David); and the selective syndication and incorporation of deviance and critique (David, Laura, and Sally), in religion writ large. All three of us are concerned with the limits of standardization and variety, especially as contained within modern capital economies. For all three of us, the key economic actor and material is the human body, in literal and figurative manifestations. Finally, together we are most fundamentally interested in the word’s derivation from Greek terms meaning “household” and “to manage,” hence: household management, or familial/communal operations and regulation. Extrapolating from the household, and moving outward, we attend to interrelations of micro and macro economic systems, the individual and familial ultimately inextricable from the local, regional, national, and global. We consider the sense in which economy expresses the management of available resources among each nested “household” constituency, and with an eye to productivity, to making something. Often that “something made” is heritage, a malleable commodity in relation to statecraft and to certain media and institutions but also strangely and simultaneously static and impermeable to all those positioned at its margins. This peculiar commodity of heritage contributes to the shape of “familial” identity at multiple levels of sociality and governance.

Revivals of interest in ancestor identification often accompany American heritage campaigns. These investments usurp the structures and warp the affects of familial generational intimacies and take institutional shape in descendant affinity groups, in multiple iterations to similar elitist patriotic ends of preserving ancestral Christian (most often Protestant) heritage: the Mayflower Society, the National Society of Colonial Dames of America, the “Sons” and “Daughters” of the American Revolution, of the Confederacy, of the Oregon Pioneers, the Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West. As this familial terminology suggests, American nation formation is vested in an economy of household management, is a process building “family” at every level. Who is part of this familial constellation? Where do they come from and how recently? How is national family constituted and structured? How are its hierarchies arranged? These are among the operative questions in numerous episodes of heritage readjustment that shape not only canonical American historical narratives but also the appearance and organization of American landed performative display. Heritage operates then as a species of statecraft, deployed and distributed in increasingly capillary increments and investments, through a range of material manifestations, institutions, and objects.3 That the LDS church hierarchy attempts to mobilize these finely tuned and finely grained energies to refine Mormon American identity and nationhood is evident in David’s examination of Don Leo Jonathan, Correlation, and the Mormon Pavilion at the 1964-65 World’s Fair in NYC. Sally’s redwoods fully invest in the work of heritage invention and consolidation, tree rings and bloodlines intertwined.

Laura’s scholarship brings alternate, more intimate and personal, familial ties to this conversation, showing how persistent micro-narratives work to oppose and resist dominant corporate pressures. Her contribution mobilizes three strong women whose performances display and/or refute male violence and its spectacularized mass media recapitulations.4 Laura offers her own domestic space, her own embodied presence, and her own voice to literally (quietly, firmly, gently, assertively) articulate this truth. She choreographs her action surrounded by intimate assemblies of personal artifacts, family photographs, and portraits painted by her artist father. The room is populated by a silent crowd of human images, a gathering of witnesses, to the precipitating events, the compounding of energies, the horror shared. Laura joins her testimony to that of Maggie Nelson to reclaim and heal the memories of Jane Mixer that circulate, many of them beyond familial control. She addresses a gendered trauma familiar to so many women. Three women, two of them caring with grace and dignity for the one who can no longer speak, two of them sharing familial as well as gendered ties. Laura joins this family; she and Maggie Nelson voice a mourning ritual for Jane Mixer. This ritual is also a protest. Behind Laura, faux police tape hanging to the side of an aqua 1950s drape with a figural print incorporates both the crime scene boundary marking of the original (police line; do not cross) and the gendered activism of this facsimile (women don’t get aids; they just die from it). Here are Laura’s own words about the scene of her video:

This was recorded in my office in my Germantown house. The fabric was a thrift store find, in it there are stylized figures eating at a cafe table, playing records, and some strange exoticized dark blue figure holding a vessel on his head. The yellow tape is from a long-ago protest in Atlanta around AIDS policy; it is police tape (I have carried it with me, there is a piece here in this office and one in my office at Temple. They come from the period not long after I was raped). There is a talismanic stuffed tiny gecko on top of the lamp (the lamp a hand-me-down from my partner David). The photographic portrait is my mother, I believe it is from her college graduation. Other images include a dear friend and colleague, a musician Sam Hsu, a beautiful pianist who was a professor at Philadelphia Bible College. There is a picture of me and David from early on in our relationship as well as an open book, a beautiful hand-made gift from my friend Ruth Ost, a hot-pink Barbie (a gift from David). There are shoes on my bookshelf and there are paintings by my father on the walls.

Economy, for all three of us, encompasses the circulation of particular images and storylines. For Laura these concern artistic familial intimacies binding and focusing opposition to a popular televised grammar and genre that threatens to sensationalize and contaminate personal memory. For Sally circulation is a relevant descriptor at both micro (redwoods and their specific images in multiple localized spaces) and macro levels. With regard to the latter, redwoods buttressed and publicized a nationally circulated iconic understanding of American identity; from late 1860s to the present they played their part in a much larger ideological orchestration of land and space in the process of nation formation. Gigantic chunks and slices of redwoods literally circulated, traveling to national and international fairs, to history and natural history museums, and to the National Mall itself as curiosities and emblems of American greatness and ingenuity. More concretely, the literally circular shape of the dead trunk’s horizontal pose exerts an oddly bounded pressure on its instantiation of family tree (tracing the national genealogies that mattered) and family circle (inviting those designated to understand themselves as citizens of a nation whose destiny was manifest, drawing a firm line excluding others from the narrative),and especially on its overlaid narrative arc of progressive history. Concentric circular repetition suggests the possibility of limitless extension, but the march of perpetuity registered on each artifact halts abruptly at its edge. The printed textual teleologies are bounded by this perimeter; the ring histories are literally framed in death. For David, to understand Don Leo Jonathan’s career is to understand the history and the circulation of Mormonism itself in the twentieth-century American imagination. And it is to see very smart people—Don Leo himself foremost among them, perhaps, but also LDS Church President David O. McKay, The Grand Wizard Ernie Roth, the (often female) heads of wrestling fan clubs, and others—tracking such circulation and theorizing ways to play with or against type, and also to invite corresponding responses, on different and variously shifting local and national stages. Stereotype, for each, reductively and strategically presses standardization to extremity, for all.

- 3See, for example, Elizabeth Kryder-Reid, California Mission Landscapes: Race, Memory, and the Politics of Heritage (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 22; and Sherry Turkle, Evocative Objects: Things We Think With (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011), 311.

- 4Maggie Nelson, Jane: A Murder (Berkeley: Soft Skull Press, 2005) and Maggie Nelson, The Red Parts: A Memoir (New York: The Free Press, 2007).

The 1960s: policy, proliferation, and constraint

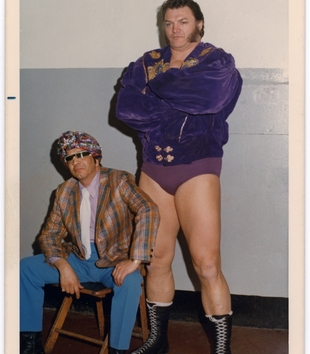

The work of all three authors harnesses the 1960s to its own particular kinds of racialized and gendered violence. David centers us squarely in this decade. Though the photograph he shares is from the early 1970s, he argues that it marks the culmination of a promotional campaign that spanned the preceding decade and which linked the professional successes of both Mormon Giant and Mormon Church. An encounter in 1963 perhaps best exemplifies this campaign in/of necessary relation. That year, Church President David O. McKay and his ecclesiastical colleagues finalized plans for a Mormon Pavilion at the New York World’s Fair. Set to occupy a prime lot near the main World’s Fair Pavilion and another structure sponsored by the Protestant Council of New York, the Mormon Pavilion was thought to mark Mormonism’s hard-won acceptance in the main line of midcentury American Christian culture. Nearly 6 million people toured the Mormon Pavilion during the 1964-65 run of the World’s Fair, and missionary attendees distributed to them over 5 million tracts and booklets. The vision that they received of Mormonism was the stuff of “Correlation,” a contemporaneous initiative to standardize church appearances, teachings, and practices and (thus also) to canonize the image of the usually white, always patriotic, conservatively dressed, clean-cut, wholesome, Jesus loving, broadly smiling missionary as symbol for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

But while David O. McKay was promoting Correlation and preparing materials for Mormonism’s star-turn in New York, he received a star of a scruffier sort in Salt Lake City: Don Leo Jonathan. Don Leo was then moving from the Midwest to California to wrestle in bigger markets, and he stopped in Utah to visit members of his Mormon family as well as church officials. Weighing on his mind at that time was a “cease and desist” letter that Don Leo had recently received from the public-relations department of the Church. Charging him with promoting a negative image of Mormonism, the letter demanded that he stop calling himself the Mormon Giant. Don Leo wanted to know what David O. McKay had to say about this—and about the shape and direction of his career overall.

Don Leo braced himself for a negative reception. Given David O. McKay’s contemporaneous image-work in venues such as the World’s Fair, one might (and Don Leo did) expect him to second or uphold the request made by his fellows in Church Information Services, to “cease and desist.” Instead the church president smiled and told Don Leo to ignore it: “they get a little zealous sometimes,” he said. Moreover he assured Don Leo that he was a wrestling fan himself. “David got it,” said Don Leo, when recalling his interaction with President McKay some 55 years later. “He got it.”5 An important part of what he “got” was the usefulness, in any standardizing measure, of maintaining just enough variety to clarify where the standard’s margins might be located. And thus Don Leo was sanctioned to continue playing at the boundaries of the would-be Mormon-American mainline, including a stint—represented in the 1974 photograph above—in cahoots with a manager dressed to evoke the putatively irreligious, un-American, and nonwhite “Other” with which Mormonism was often compared in the pre-Correlation era: Islam.

The 1960s also figure for Laura and Sally, though perhaps not yet so obviously in the 2000 character pieces that elicited this larger conversation. In Laura’s work, Jane Mixer’s assailant in Michigan fired the fatal bullet into her head in March 1969, and then, in apparent rage or fear or revulsion, strangled her already lifeless body with her stocking, a sequence relayed by her corpse on the autopsy gurney, in the location of blood, pooling bright blue, above her eyes. The unrehearsed flare of brutality in Laura’s essay meets the plotted, staged aggressions of David’s and both run head-on into a peculiar coagulation of impulses in 1960s legislative measures and actions narrated in Sally’s work on public display. This decade’s production of American policy, Sally suggests, exposes a violence multifold in its historical choreographies and environmental impacts. Humming in the background of the decade’s aggressive orchestrations of racial and religious “otherness” was the 1965 military deployment of United States ground troops in the Vietnam War (bodies in the air or on sea before; bodies on the ground thereafter). In 1966, a year after immigration and civil rights reforms provided legal avenues and protections (on paper at least) for more racially diverse religious communities to claim public space in the United States, and as these groups energetically exercised these new rights, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act, regularizing heritage preservation policy and supplying an annual source of tax-supported funding for related projects. Building on over two centuries worth of accrued white Protestant accomplishment in the work of national heritage formation, these measures effectively (though not with uniform intentionality) secured the prior material claims of the nation’s Anglo-European Christian past.6 Successful American heritage preservation, according to its 1960s architects, would “give a sense of orientation to our society, using structures and objects of the past to establish values of time and place.”7 Events and decisions of the mid-1960s, then, both legitimated claims of American religious and racial difference and simultaneously elicited state sanctioned white Christian heritage retrenchment that consumes the choicest American spaces into the present. (The LDS strategy of Correlation aimed to more firmly ensconce the Mormon Church within the parameters of this white Christian frame.)

That heritage would be racialized in a religio-political system where the construction of race and so much else has been made to depend on family and bloodlines should come as no surprise. By definition, heritage is something that can be inherited or handed down in direct (familial) descent. As such it is genealogically and biologically driven and thus purportedly “given” in senses literal and figurative. Family ties of various sorts figure prominently in each of our subjects: a poet niece labors to reclaim from “true-crime” television the narration of her aunt’s vicious murder; and a “Mormon giant” wrestler paradoxically performs white religious genealogy for self and church in a period of LDS “correlation” and consolidation. Giant slices of redwood trees, immobilized for display, recite key dates in Anglo-Protestant history, charting an American genetic ascendancy that valorizes masculinity, colonization, and the violent occupation of lands.8 Condensed labels, an economy of words, at first glance seem generic and bland, denying their precise curations of whitewashed events, naturalizing and thus concealing the process of selection. The tree on the “Avenue of Giants” pictured in Sally’s tightly abbreviated piece, for example, fell as recently as 1987, demonstrating the longevity of this practice. Its “rings of history” shout out the Magna Carta’s signing (1215), Columbus’s “discovery” of America (1492), Drake’s landing in California (1579), the Pilgrims’ landing at Plymouth Rock (1620), the Declaration of Independence (1776), the discovery by land of Humboldt Bay (1849), and the founding of the Save-the-Redwoods League (1919). Three of the more unusual choices (Drake, Humboldt, Save-the-Redwoods) clarify the national-genealogical-religious intent and subtext of the four adjacent standards (Magna Carta, Columbus, Pilgrims, Declaration). Californians used Drake to secure British and Anglican heritage for their state (their white Protestant “New England” thus predated by four decades the Pilgrims’ at Plymouth Rock) and grab historical precedence from Spanish and Mexican Catholics. Remarking the “discovery” by white men of land passage to Humboldt Bay in 1849 likewise pressed heritage into molds manufactured by race and religion, obfuscating directly related genocidal campaigns against California’s Native Americans; some of the worst massacres targeted Humboldt Bay’s Wiyot tribe.9 The 1919 founding of the Save-the-Redwoods League superficially appears to be the most benign event recorded on this display. As Jared Farmer has shown, however, the league’s founders, Madison Grant, Henry Fairfield Osborn, and John C. Merriam, assembled an organization that resembled a veritable “who’s who of eugenics” and nativism, pseudo-scientifically propping up a national white Protestant racism, so “naturally” systemic that it could be revealed to thrive in histories registered on ancient trees.10 At the formal 1931 dedication of the Founders Tree (the “world’s tallest tree”), named to honor Grant, Osborn, and Merriam, a celebrant intoned: “It is an ancient and racial urge that has brought us together today.” Anglo-Saxon America reigned in the redwood preservation movement as in the wanton capitalist environmental destruction necessitating these efforts.

- 5David had the good fortune to meet with Don Leo several times before he passed away in 2018. These quotes are from an interview on June 1, 2015 in Langley, British Columbia, Canada.

- 6See Nicolas Howe, Landscapes of the Secular: Law, Religion, and American Sacred Space (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 49-50, on the relationship between claims on/contests in public space and increasingly active pluralization of American religions.

- 7With Heritage So Rich: A Report of a Special Committee on Historic Preservation (Albert Raines, chairman, and Laurance G. Henderson, director) under the auspices of the United States Conference of Mayors with a grant from the Ford Foundation (New York: Random House, 1966): 207; the quotation is taken from the volume’s important final section of “Findings and Recommendations.”

- 8Freeman Tilden’s classic, official, and massively influential guide to National Park interpretation and education recommended as exemplary precisely this kind of display: “To take a slice of a tree like the giant sequoia, and to associate its growth rings with a time chart of our human history, was an idea that occurred to some master interpreter” (italics added); Tilden, Interpreting Our Heritage (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007 [1957]), 27. He also explicitly discouraged the use of cumbersome scientific terminology in interpretive display and performance, using the word “dendrochronology” among those he intended to make this negative point; Ibid., 41. By the late nineteenth century, the impressive trees, excessive in most every sense, had their own purportedly scientific migration story; these giants undoubtedly came “from the North.” See Jared Farmer, Trees in Paradise: A California Story (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2013), 71-72.

- 9Benjamin Madley, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016).

- 10Farmer, Trees in Paradise, 69-70.

Material Excess

Encounters with material excess—or with particular representations of excess—can effect affect (that is, they can heighten or lessen affective responses) and thus shape one’s sense of genealogical relations (i.e., they can shape genealogies of concern). For Laura and David, this concern manifests in a desire to redirect attention away from—and thus also to resist the incorporating programmatic impulses of—reality-show television of different sorts: the crime show and the televised wrestling match. Maggie Nelson and Don Leo Jonathan both recognized that television scripting does a kind of deep cultural work, even as (or precisely because) it allows for decidedly shallow viewing. Hence Maggie Nelson’s interest in reframing the depiction of Jane Mixer’s death, as represented in the passages that Laura reads, and also Don Leo’s excitement about discussing with David the cultural significance of his career rather than the shape of some particular move. (During their first conversation, Don Leo, then in his late 80s, expressed exhaustion at fielding decades of requests to “tell me again about how you body-slammed Andre the Giant!”) Blood and gore sells televisions, no doubt, and the abject attracts interest. But both Maggie Nelson and Don Leo wielded bodies and made art by working the borders between attraction and repulsion. In Sally’s work, tree rings are made to conceal the racist redirections of history that account for their labels. Here the excess and its redirections contain the violence denied, the property ownership demanded, elided, and obscured, the care-less genocide (human and arborial) demanded by the invention of canonical genealogical narratives of American heritage. The excess harvested from the redwoods is unrelenting; it has included such artifacts as the “One Tree [Baptist] Church” in Santa Rosa that merited an early “Ripley’s Believe It or Not” entry and attained a second life as a Ripley’s Museum; the One Tree houses that literally domesticated their own materiality; the redwood “postcard” relics made of the body of the tree itself, printed with divinity-invoking poetry, designed to be sent through the mail; the “Shrine Drive-Thru Tree Park[s].” Human abuses of these ancient giants produced an endless exercise in the multiplication of capital extravagance and its pretenses of benevolence. Not only were tree rings counted, but trees were named, as individuals, time again, almost exclusively after powerful white men, very often military officers, politicians, naturalists, “settlers.” These named trees approximated contemporary sculpted monuments in bronze and marble. The trees bested by far the scale of anything Europe had to offer; they commemorated “heroic” white American masculinity and magnified the patriotic aura of redwood “cathedrals.” Named in 1867, the General Grant Tree, for example, was then thought to be the largest tree in the world (the General Sherman Tree superseded it in 1931). Since 1925 Christmas observances have taken place in the presence of the tree. In 1926 President Calvin Coolidge declared the Grant Tree the “Nation’s Christmas Tree”; the National Park Service lays an annual Christmas holiday wreath at its base. In 2018, Erika Owen, writing for MarthaStewart.com, described a Christmas visit to the General Grant Tree as a must-have on the “ultimate bucket list for holiday travelers." In 1956, President Dwight D. Eisenhower proclaimed the Grant Tree a National Shrine, a memorial to the nation’s war dead. It is the only living federally recognized National Shrine to this day.11

- 11James Clifford Shirley, The Redwoods of Coast and Sierra (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1940), Section 3, “Sequoia, Name of the Redwoods,” available here. Shirley's book was first published in 1937; we cite the 1940 edition because the National Park Service selected this version for its nps.gov website. In this same volume, see also Section 4 “Distribution of the Redwoods,” and Section 10, “Size of the Redwoods”; Erika Owen, “Visit the General Grant Tree: A Living Sequoia Called the “Nation’s Christmas Tree,” Martha Stewart, 15 November 2018 [article no longer available]; on the Grant Tree’s national history, see the official National Park Service web page’s “The General Grant Tree.”

Constraints of Variety and Standardization

The “programmatic impulses” resisted in David and Laura’s work here and the patriarchies and heritage recitations performed by Sally’s historical subject are each engaged in practiced labors of standardization. Laura exposes and joins Maggie Nelson in resistance to standardized misogynies, masculinities that objectify female bodies, and masculinities that feed the breathless sensationalism of true crime reality TV. Sally and David consider the construction of standardized narratives of national identity—the work of American genealogy, in a sense—during a 1960s moment of increasing racial and ethnic diversity. Federal park managers and other representatives of statecraft and its public facsimiles plotted national history in terms of (and as the culmination of) western progress, illustrating their narratives by marking a limited range of “cultural milestones” against the lifelines of felled trees. Meanwhile, the Mormon Church worked hard to place itself in the mainline of U.S. religious history (and thus also western progress) through imaginary and promotional “correlation” with conservative “American values.” Don Leo Jonathan’s career as “the Mormon Giant” tells us much about the limits of Mormonism’s putative mainstreaming—or perhaps better, the mechanisms of its de facto mainstreaming—in 1960s America. Yet in both cases (David’s and Sally’s) the making of an essentially white or Anglo heritage involved also the selective play of racial difference, or at least the selective incorporation of “Other” referents. Whites in America have claimed to be “native” by playing Indian (to use Philip Deloria’s term), by laying claim to aspects of “classical” Asian history elevated to that end (see for instance the celebrations of Chinese paper-makers in some dendrochronologies that serve simultaneously to align white western viewers with ancient Chinese accomplishments while distancing viewers and “ancestors” alike from the actual Chinese people in their modern midst), or by winking at any possibility of racial aberrance from a position of a hard-won presumptive whiteness (as in Don Leo’s case). In all instances, crucially, standardizations (mainstreams) of genealogy and national identity alike are created through strategic education and the selective race-and gender-play of white groups.

We are each, in quite different ways, dealing with what Kathryn Lofton has called “the performance of constraint’s practice."12 Here all three of us query performances that tend toward and enforce standardization and, at least implicitly and by comparison for David and Sally, and explicitly for Laura, with performances that reject centripetal energies. There is much more to be said along these lines—and we can do better to meet Lofton’s challenge, as well as MERA’s invitation to find robust illustrations of religion in American economy and economy in American religions—both by looking deeper and by considering more broadly the variability that is incorporated within constraint’s practice. A closer investigation of each of our case-studies reveals that it—constraint’s practice—usually entails the coining, the underwriting, and the selective circulation of symbols either of unconstrained excess or else of limited-run oddity. Professional wrestling screams at us: For every hard-working American type to “work,” there must be a profligate wastrel lurking somewhere in the wings. For every Mormon missionary drive there must be at least one Mormon mauler. For a pivotal generation in Mormon history, Don Leo was that Mormon mauler. A good part of Don Leo’s career consisted in playing a dirty-dealing ruffian—and later also a stablemate of other religious outsiders under the direction of a “Muslim” manager—at a time when Mormons in general were winning greater acceptance as law-abiding, clean-cut Christians. Perhaps the two most significant things about Don Leo’s career for students of religion in America are that he had much to say about his work as a peculiar type of “Mormon missionary” in a particular “Mormon moment”; and also that LDS Church leaders sanctioned his work as such even while “Correlating” a very different image elsewhere. David O. McKay “got it,” after all. He got that Don Leo’s career generated a certain, delimited controversy that might funnel inquiries into more clean-cut, Correlated initiatives elsewhere. Sooner or later Don Leo fans might find themselves also at the Mormon Pavilion.

This conversation relates to Laura S. Levitt’s research into Maggie Nelson, Sally M. Promey’s study of tree rings and blood lines, and David Walker’s examination of Mormon wrestler Don Leo Jonathan.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.convo.2022.1

1. Laura Levitt, Sally Promey, and David Walker, "American Performances, Economies, and Genealogies of Constraint," Conversation, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.convo.2022.

Levitt, Laura, Sally Promey, and David Walker. "American Performances, Economies, and Genealogies of Constraint." Conversation. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.convo.2022.