Sally M. Promey is Professor of American Studies and Professor of Religion and Visual Culture at Yale University. She holds a secondary appointment in the Department of Religious Studies and an affiliation with the Department of History of Art. She is Director of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion. Her publications include Painting Religion in Public: John Singer Sargent’s Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library (Princeton University Press, 1999) and Spiritual Spectacles: Vision and Image in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Shakerism (Indiana University Press, 1993). More recently she is co-editor, with Leigh Eric Schmidt, of American Religious Liberalism (Indiana University Press, 2012); and editor of Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice (Yale University Press, 2014). Religion in Plain View: Material Establishment and the Public Aesthetics of American Display is under contract with University of Chicago Press

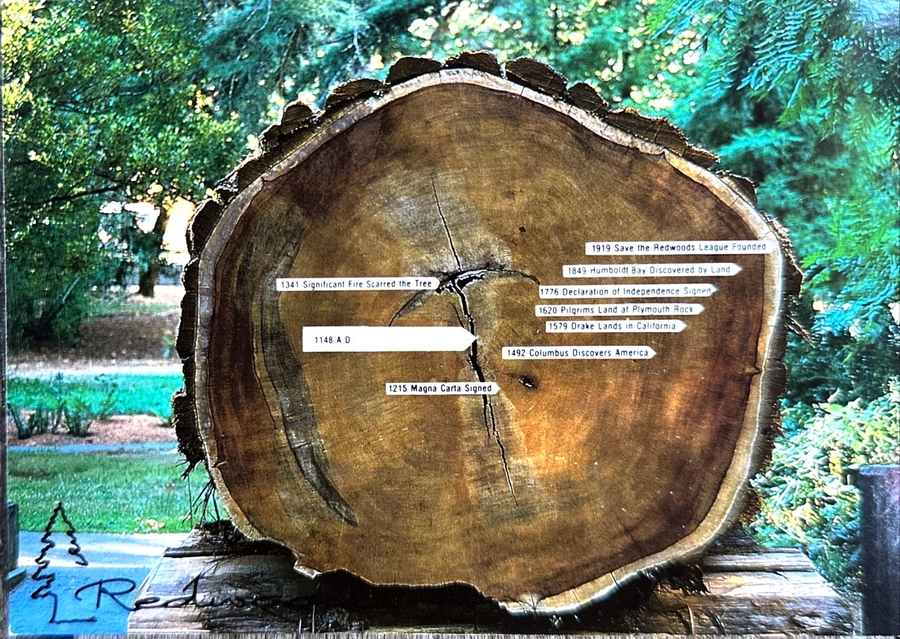

The dismembered carcass of a tree stakes out the perimeter of these remarks, a trunk section of a felled redwood, laid out at right angle to the once-living stalwart’s vertical stance, its diameter still significantly higher than the average upright human being is tall. One instance of such an artifact might be judged a singular curiosity, an idiosyncrasy, hardly enough on its own to signal any authoritative consolidation of the nation’s genealogical investments. Its iteration in multiples, however, in California’s redwood parks and roadside rests and in various image formats collected by tourists and displayed in classroom science units and at show-and-tell in public schools, is another sort of thing entirely. By the 1930s, this kind of object, a giant cut of redwood with textual arrows marking out, as Park Ranger James Shirley declared, “familiar events of the Christian Era which occurred within the lifetime of this tree,” had become a standard feature of state and national park education.1

- 1 James Clifford Shirley, The Redwoods of Coast and Sierra (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1940), 80.

Sowing Anglo-Christian history into natural science, circular redwood monuments bio-marked key dates, naming (depending on the age of the tree) “Christ Born,” “Saint Paul in prison,” “Destruction of Rome by barbarians,” “First Crusade,” “Magna Carta Signed,” “Discovery of America,” “Landing of Pilgrims,” and “Declaration of Independence.” This matching of a massive tree’s growth rings to curations from a racialized religious past carried the weight of the new science of dendrochronology. The practice was a customary feature in public interpretation of coastal and Sierra redwoods by various governmental and quasi-governmental groups, the tourist industry, environmental organizations, and heritage enterprises into the twenty-first century.

These objects are both family trees and family circles, literally naturalizing a canonical “American” familial heritage insistently recited and instantiated in many media and locations: artistic and built environments, judicial practice, legislation and policy, textbooks, land use, and national land theory. Heritage is a family business. Importantly it traces figurative bloodlines while also establishing extravagant claims to “home” territory, to landed space, to rootedness where it has few or no roots, to a kind of belonging that rests on the eradication or ejection of others with prior rights. Leaders in various preservation movements wrote white Christian supremacy into the national fabric. Garish corpses of redwood trees, limbs amputated, bodies sliced and framed, blocked, or elevated to immobility, bolstered this recitation of grand white destinies. Unwittingly they also publicly displayed the violence and downfall of American empire.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.21

1. Sally M. Promey, "Tree Rings and Blood Lines," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.21

Promey, Sally M. "Tree Lines and Blood Lines." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.21.