MAVCOR Journal is an open access born-digital, double blind peer-reviewed journal dedicated to promoting conversation about material and visual cultures of religion. Published by the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion at Yale University and reviewed by members of our distinguished Editorial Board and other experts, MAVCOR Journal encourages contributors to think deeply about the objects, performances, sounds, and digital experiences that have framed and continue to frame human engagement with religion broadly understood across diverse cultures, regions, traditions, and historical periods.

MAVCOR began publishing Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion in 2014. In 2017 we selected a new name, MAVCOR Journal. Articles published prior to 2017 are considered part of Conversations and are listed as such under Volumes in the MAVCOR Journal menu.

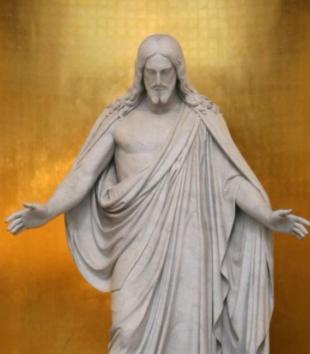

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Christus (Christ)

Bertel Thorvaldsen, Christus (Christ)

The internationally famous Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen (1789–1838) was asked to produce a series of colossal statues of Christ, John the Baptist, and the apostles for the new Neoclassical Vor Frue Kirke of Denmark. Of these, Christus (Christ) has become best-known. Copies of the sculpture, often true to size or even larger, can be found around the world.

Rabbi Jordie Gerson: Reflections on Images and Jewish Traditions

Rabbi Jordie Gerson: Reflections on Images and Jewish Traditions

Ashley Makar spoke with Rabbi Jordie Gerson on October 26, 2010 at Yale University’s Joseph Slifka Center for Jewish Life. Rabbi Jordie Gerson currently works as the Assistant Director and Campus Rabbi at University of Vermont Hillel.

Barquitos del San Juan: La Revista de los Niños, Year 13, No. 23, 2007

Barquitos del San Juan: La Revista de los Niños, Year 13, No. 23, 2007

Rolando Estévez Jordán, a visual artist, and Alfredo Zaldívar, a poet, co-founded Cuba’s Ediciones Vigía (Watchtower Editions) in 1985 to create an open forum for writers, musicians, and artists.

Carte de visite Photograph Album

Carte de visite Photograph Album

What photograph albums teach us about nineteenth-century viewing habits is that the reach of religion extended beyond compositionally “religious” subjects. Modes of beholding were often forms of religious practice that did not require a regulated rift between sacred and secular.

Alexander Anderson, Abigail Hutchinson: A Young Woman Hopefully Converted

Alexander Anderson, Abigail Hutchinson: A Young Woman Hopefully Converted

That “Protestants don’t have pictures” remains a common generalization. Yet in the early nineteenth century, nothing could be further from the truth. Protestant publishers like the nonsectarian American Tract Society (ATS) lavishly decorated their tracts with small but expressive printed illustrations.

The Chapel of Our Lord of the Miracles (La Capilla de Nuestro Señor de los Milagros), San Antonio, Texas

The Chapel of Our Lord of the Miracles (La Capilla de Nuestro Señor de los Milagros), San Antonio, Texas

No exact date is known for the founding in San Antonio, Texas, of the Capilla de Nuestro Señor de los Milagros (Chapel of the Lord of Miracles), or Capilla de los Milagros, as it is sometimes called. Visitors to the shrine and its central Christ image offer both their orations and material expressions of prayer.

Opening Virgin (Vierge Ouvrante)

Opening Virgin (Vierge Ouvrante)

This object is an example of a type of small-scale Christian moveable-part medieval sculpture called a Vierge Ouvrante (“Opening Virgin”).

Traveling Image of the Holy Child of Atocha (Santo Niño de Atocha), Plateros, Mexico

Traveling Image of the Holy Child of Atocha (Santo Niño de Atocha), Plateros, Mexico

Each year, certain special religious images are ceremonially brought from Mexico and Central America to visit Catholic devotional communities in Southern California. These devotional statues of Catholic saints are “imágenes peregrinas,” pilgrim or traveling images.

Arthur B. Davies, Sacramental Trees

Arthur B. Davies, Sacramental Trees

Two maidens, one bright and one shadowy, lead an ox through a curiously dense, shallow, and cubistically-fragmented woodland, heading (one presumes) through the titular sacramental trees and towards an uncertain destination.

Drain-spout in the Form of a Flying Celestial Figure

Drain-spout in the Form of a Flying Celestial Figure

Hovering above the central courtyard of a Hindu monastery at the rural central-Indian village of Chandrehe was once a set of finely sculpted flying celestials, known within their original, tenth-century context as gandharvas, heavenly singers in the court of the gods, or vidya-dharas, meaning “carriers of truth.”

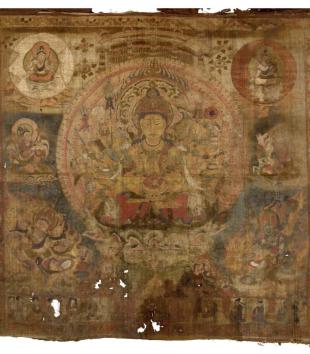

Thousand-armed and Thousand-eyed Avalokiteshvara

Thousand-armed and Thousand-eyed Avalokiteshvara

Avalokiteshvara, one of the most important bodhisattvas in Buddhism, was popularly known as the “perceiver of the world’s cries.” Bodhisattvas, meaning literally “enlightened beings,” were devoted, out of a deep sense of compassion, to aiding other sentient beings in their quest for enlightenment, even to the point of postponing their own entry into nirvana.

The Vincent and Mary Markham Monument

The Vincent and Mary Markham Monument

In the summer of 1900, Denver acquired an unusual sculpture to mark the last resting place of pioneer attorney Vincent Daniel Markham (1826-1895) and his wife Mary (ca. 1834-1893).

Cuzco Miter

Cuzco Miter

The Cathedral of Cuzco, Peru holds several liturgical ornaments from the Spanish colonial period in its treasury. Among them is a magnificent embroidered miter, the headdress worn by bishops for blessings, baptisms, and processions.

Kwame "Almighty" Akoto, The Supernatural Eyes of God

Kwame "Almighty" Akoto, The Supernatural Eyes of God

During a trip to Ghana in May 2010, I visited the roadside shop and atelier of painter Kwame Akoto, alias “Almighty,” a name he adopted so as to praise the power of God.

Rightly Dividing the Word of Truth

Rightly Dividing the Word of Truth

Clarence Larkin’s dispensationalist chart “Rightly Dividing the Word of Truth” (1920) offers a detailed schematic of biblical history. The artistic product of an individual with experience in mechanical draftsmanship, Larkin’s chart shows how events and epochs fit together like parts in a salvation machine.

Icons move. They cross national borders and traditional boundaries. They show up in the least expected places.

Ancestor portraits at Mogao Cave 231

Ancestor portraits at Mogao Cave 231

The integration of “secular” figures into a Buddhist cave complicates the separation established by both medieval Chinese authors and modern scholars of Buddhist art between practices of familial commemoration and religious devotion.

Hans Holbein the Younger, Dead Christ Entombed

Hans Holbein the Younger, Dead Christ Entombed

“Why, some people may lose their faith looking at that picture!” Dostoyevsky famously had his fictional character Prince Myshkin exclaim over Hans Holbein the Younger’s Dead Christ Entombed.

Skull boxes

Skull boxes

Skull boxes that both memorialized a dead individual and displayed the deceased person’s skull were made in Brittany from the eighteenth century to about 1900.

These glass eyes seem to look intently at the viewer, seizing the viewer’s attention. This is precisely what they are intended to do by the Shvetambar Murtipujak Jains of western India; it is also precisely why the Digambar Jains of western India strenuously object to them.

The Virgin of Guadalupe, Extremadura, Spain

The Virgin of Guadalupe, Extremadura, Spain

This Marian icon cannot be characterized as a single object as the perception of her authenticity, from which she gains her numinous power, draws on two distinct representations, one nested inside the other.

The Dolgellau Chalice and Paten

The Dolgellau Chalice and Paten

In 1890 two men working in the area around Dolgellau in North Wales discovered this pair of objects in a crevice between rocks. Encrusted with soil and plant matter, the objects were not at first identifiable.

The Cross of Motupe

The Cross of Motupe

Credited with saving the town from sure disaster, the Cross of Motupe became the centerpiece of a devotion that drew pilgrims from throughout the region, and eventually from throughout Peru.

Asher Durand, In the Woods

Asher Durand, In the Woods

In June 1840, Asher Durand wrote in his journal: “Today again is Sunday. I have declined attendance on church service, the better to indulge reflection unrestrained under the high canopy of heaven, amidst the expanse of waters—fit place to worship God and contemplate the wonders of his power.”

Buddhist votive stele with carved Buddhist figures and inscriptions

Buddhist votive stele with carved Buddhist figures and inscriptions

This is a Buddhist votive stele made in the sixth century in north central China. It probably stood either in the courtyard of a Buddhist monastery, or in a public place such as a market square, or at a major crossroads.

Benjamin Paul Akers, St. Elizabeth of Hungary

Benjamin Paul Akers, St. Elizabeth of Hungary

Given the fact that Benjamin Paul Akers was a Protestant working at a time when nativist and anti-Catholic sentiments ran high in the United States, his choice to depict a miracle performed by an Eastern European saint seems peculiar, as does the popularity of his sculpture.

Barnett Newman, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani

Barnett Newman, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani

According to the art critic Harold Rosenberg there is nothing religious about Barnett Newman’s series of fourteen roughly human-sized, black and white paintings, The Stations of the Cross: Lema Sabachtani.

Mary Lyman’s Mourning Piece

Mary Lyman’s Mourning Piece

Mary Lyman’s mourning piece served as visual and material evidence of her education, participation in mourning practices, and her religious and social formation.

Madonna of the Fire

Madonna of the Fire

Forlì's Madonna of the Fire is a large fifteenth-century woodcut almost twenty inches high and sixteen inches wide.

Christ Crucified in the Gellone Sacramentary

Christ Crucified in the Gellone Sacramentary

The image of Christ on the Cross, either as an element of a narrative scene (a Crucifixion) or as an isolated object of devotion (a Crucifix) is so common in the artistic and religious traditions of the last millennium of Western art, especially but not only in the Catholic tradition, that it is seldom recognized that such images are altogether absent during the first centuries of Christianity, and remain rare at least through the eighth century of the common era.

Te amo heart

Te amo heart

This object was purchased in an upscale novelty shop catering to tourists in downtown Boulder, Colorado, in 2010 for $11.95. Although at first blush it appears to be a Sacred Heart of Jesus, on second look the banner, which reads “te amo,” Spanish for “I love you,” indicates that the heart may not belong to Jesus.

The Jade Buddha for Universal Peace

The Jade Buddha for Universal Peace

Numerous photographs appear to reveal what adherents are calling “mandala lights” around the Jade Buddha for Universal Peace as it makes its way around the world on a tour of Buddhist temples, monasteries, town squares, and museums.

Carved rock outcropping, Machu Picchu

Carved rock outcropping, Machu Picchu

For the Inca, the landscape was both sacred and animate, full of forces that demanded respect and offerings. Distant mountain peaks, called apu—a term of respect meaning “lord”—were among the most powerful of these forces.

Chicken-Feeding Girl

Chicken-Feeding Girl

To most modern visitors, the Chicken-Feeding Girl displays the stereotypical concern of a doting mother, and a number of scholars have described this image as representative of the pastoral life of the region during the Song Dynasty (960—1279 CE). While this is in fact one way to interpret the work, the Song dynasty audience for Chicken-Feeding Girl read her presence at the site in an entirely different manner.

Repurposed Choir Loft, Lake View Lutheran Church (ELCA), Chicago

Repurposed Choir Loft, Lake View Lutheran Church (ELCA), Chicago

Lake View Lutheran Church on Chicago’s north side is the fourth building of a congregation founded by Scandinavian immigrants in 1848. About 1960, demographic changes pushed the congregation to relocate and rebuild.

Death Cart (La Muerte en su Carreta)

Death Cart (La Muerte en su Carreta)

This dramatic death cart is an object that was used in acts of corporal penance performed by the Hermanos de la Fraternidad Piadosa de Nuestro Padre Jesús Nazareno (Brothers of the Pious Fraternity of Our Father Jesus of Nazareth).