Meg Bernstein is an art and architectural historian who specializes in medieval Europe. She is a Postdoctoral Associate at the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale University for the 2020-21 academic year. Meg earned her PhD in Art History from the University of California, Los Angeles in 2019. She has taught at UCLA, the Courtauld, the Rhode Island School of Design, and Columbia University.

The Visitation

The Visitation

Crystal Mary

Crystal Mary

Madonnenfigur (Madonna Figure)

Madonnenfigur (Madonna Figure)

Figurengruppe (Group of Figures)

Figurengruppe (Group of Figures)

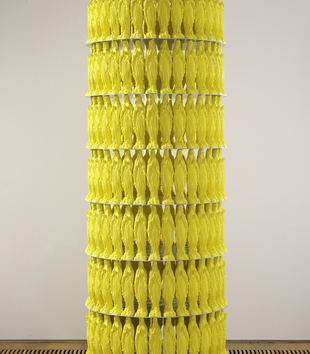

Warengestell mit Madonnen (Display Rack with Madonnas)

Warengestell mit Madonnen (Display Rack with Madonnas)

The Portinari Altarpiece

The Portinari Altarpiece

Barbie billboard in Times Square

Barbie billboard in Times Square

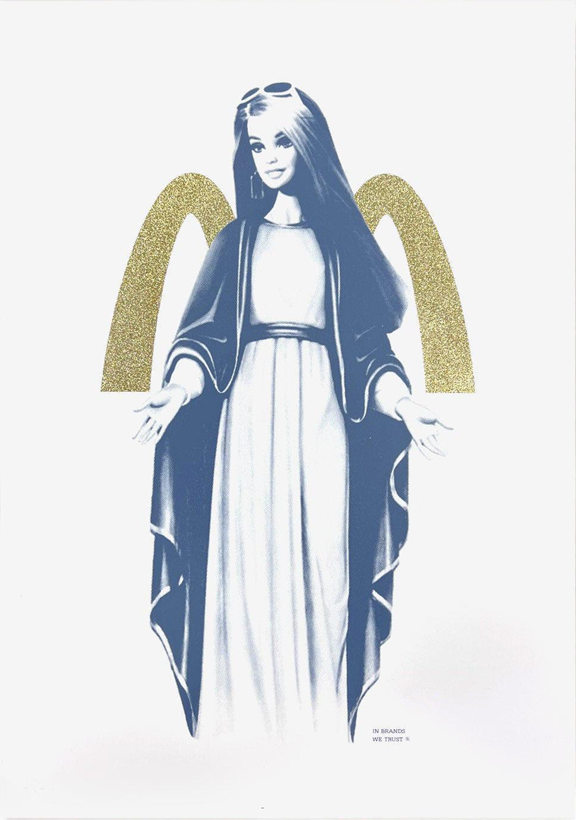

In Brands We Trust (Chrome)

In Brands We Trust (Chrome)

In Brands We Trust (Fiberglass)

In Brands We Trust (Fiberglass)

In Brands We Trust, two sculptures in progress

In Brands We Trust, two sculptures in progress

In Brands We Trust – Barbie Halo Edition

In Brands We Trust – Barbie Halo Edition

In Brands We Trust – Large Wings

In Brands We Trust – Large Wings

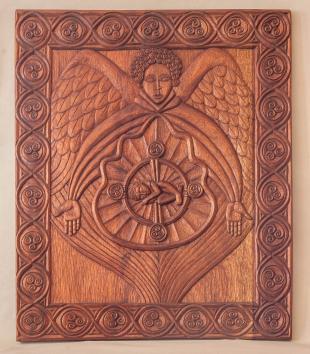

Annunciation

Annunciation

Maestà

Maestà

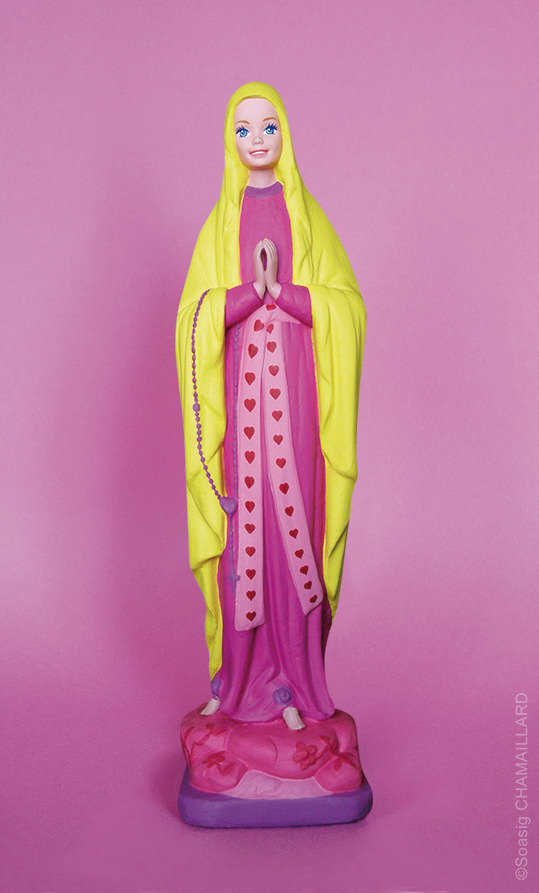

Sainte Barbie AA

Sainte Barbie AA

Sainte Barbie

Sainte Barbie

Bedazzled, flocked, clad, spangled, stellated, fractured, crystallized: the figures we bring together in this Constellation are positioned in a network that stretches across the sacred, the mystical and the kitsch; sitting amongst the extraordinary and the everyday. Their forms are markedly similar, although their surfaces and dimensions are various—presenting a beguiling range of textures, factures, planes, scales, beings, and becomings to the eye. Sharing an iconic form, their individual meanings and narratives are variously refracted through the shimmer of rock crystal and faceted geodes, covered with brightly colored polyester, pigment, or polychrome plaster, enameled, cast in copper and metal and spangled with glitter. These works bracket the medieval and the (post)modern, and range from the sublime to the quotidian.1 As objects that operate on a formal, thematic spectrum of being/meaning bound up in the iconic form of and fluid, multifaceted understandings around the “Virgin,” they vacillate from the natural to the supranatural, and operate on a sliding scale of material significance and object-based ontology. In so doing, they ask questions that shift from those of spiritual, metaphysical seeing, characteristic of medieval art,2 to the material production and location of value in the iconic forms of consumerist capitalism and in/of endlessly replicated objects (sometimes turned artworks).3

- 1For the usefulness of this transhistorical approach, see Alexander Nagel, Medieval Modern: Art out of Time (New York: Thames & Hudson, 2012); Alexander Nagel and Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance (New York: Zone Books, 2010).

- 2Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994); Elizabeth Sears and Thelma K. Thomas, eds., Reading Medieval Images: The Art Historian and the Object (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002); Elina Gertsman, Worlds Within: Opening the Medieval Shrine Madonna (University Park: Penn State Press, 2015); Herbert L. Kessler, Experiencing Medieval Art (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2019).

- 3Clement Greenberg, “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” Partisan Review, 1939; T. J. Clark, “Clement Greenberg’s Theory of Art,” Critical Inquiry 9, no. 1 (1982): 139–56.

Consumption and replication, in fact, are two of the linchpins of this Constellation, whereby (repurposed) iconic forms consume original narratives, and, in this consuming, transform them into something else, something other. As Kathryn Lofton provocatively states in Consuming Religion, “consumption is loss”;1 however in the objects we bring together here, and as she also acknowledges, consumption can simultaneously be generative, productive, fertile. A shift, rather than something that obliterates or destroys. In this practice/process inserted materials obscure, unmake, and remake the original, lending new identities and new symbolic significances to the shifting, shifted forms of these figures. Objects, here, largely exist in multiples rather than singularities, doubling and folding and repurposing replicated narrative and object across time and space, in a type of conceptual mise en abyme that deals in the insertion of multiplicities as well as in multiples. If this Constellation had a theme tune, it would be displayed to Madonna’s iconic 1984 track “Like a Virgin,” while concurrently asking “what is unlike a Virgin” through its attention towards material, to materiality, to meaning/making as read across and around form in this group.

- 1Kathryn Lofton, Consuming Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 1.

Our starting point for compiling this particular set of objects was a chance, Warburgian concordance between the fourteenth-century Katharinenthal Visitation pair in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Figs. 1a, 1b) and Kyle Montgomery’s contemporary crystal Virgin sculptures (Fig. 2), both of which produce an anachronic response to ideas of how the luminous and crystalline can fuel awe and devotion from within the nucleating site of a sacred body.1 Both of these sets of artworks rely on the fracturing of the “original” body to produce new types of knowingness/beingness; one produced in both cases by an additive assemblage of rock crystal to figure. In the case of the Visitation, this fracturing is used to heighten the mystical and metaphysical nature of an iconographic moment, actualized through the sculpted figures and through the inclusion of rock crystal covered cavities,2 applied onto the painted and gilded abdomens of the wooden figures, through which, it is suggested, the miraculous vision of the bodies of the infants carried in utero by Mary and Elizabeth may have been imagined to be seen.3 The other type of fracturing or fusing of form in these paired examples is created by the shattering insertion of a geode which simultaneously erodes and supplants the face and torso of the original figure of the found Virgin, and continues to do so over and over and over in a process of human-mineral hybridization of form, figure, and face in an artistic practice adjacent to a night of the geological body-snatchers. Here, harmonic forms of mineral matter come to stand for an individuated figure, which, like a geode, has been cracked open to reveal a sparkly mass within its framing form. Despite their distinct approaches to the creation of these crystalline works, these pieces are in material and iconographic conversation with each other, narrowing the 700-year gulf between their production. The interwoven, atemporal connections between the crystal Virgins and the Katherinenthal Visitation serve to promote fluid and mutable other-worldly sensations around these forms, which nevertheless maintain iconic narrative resonances for their viewers, amplified through shimmering crystalline material insertions into sculpture. These forms center on the unknown and unknowable, as much as the known and the narrative, exploiting their object-identity as tangible, speaking, materially complex things through both the original form of the sculpture, and through the play of the crystal. This dialogic process is enabled by the stable framing form of the figure but is ultimately reliant on the opacity and mystery of the crystals they contain to connect these works across time and space.

- 1On the Bilderatlas Mnemosyne, Aby Warburg’s unfinished sets of image boards linking visual themes across time, see "Bilderatlas Mnemosyne," The Warburg Institute, accessed August 14, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/f7b2c60c-4c53-4f7d-8985-5c5207bcf04e; "Pilgrimage: A 21st-Century Journey to Mecca and Medina," The New York Times, July 21, 2016, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/093751fb-ee6d-44e4-b1f6-86768de1de88; Christopher S. Wood, A History of Art History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2019); Christopher D. Johnson, Memory, Metaphor, and Aby Warburg’s Atlas of Images (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2021); On the Katharinenthal Visitation pair, see Jacqueline Jung, "Crystalline Wombs and Pregnant Hearts: The Exuberant Bodies of the Katharinenthal Visitation Group," in History in the Comic Mode Medieval Communities and the Matter of Person, ed. Rachel Fulton Brown and Bruce Holsinger (New York: Columbia University Press, 2007), 223-37, https://doi.org/10.7312/fult13368-021.

- 2Karen Overbey, "Seeing through Stone: Materiality and Place in a Medieval Scottish Pendant Reliquary," RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 65/66 (2014): 242-58; Genevra Kornbluth, "Active Optics: Carolingian Rock Crystal on Medieval Reliquaries," Different Visions 4 (2019), http://hdl.handle.net/10079/6aa65bbd-3e98-43ee-8950-4bf520cfa82c; Cynthia Hahn and Avinoam Shalem, eds., Seeking Transparency: Rock Crystals Across the Medieval Mediterranean (Berlin: Gebr. Mann Verlag, 2020).

- 3Luke 1:36-56.

Montgomery’s sculptures, which repurpose mass-produced chalkware Marian figures, utilize a similar impulse some seven hundred years later to ask further questions about recognition and knowing through the presence of matter, object, and rock.1 Montgomery’s practice, which has its roots in collage, is largely concerned with “the unknown of the earth and life, the powers and knowledge of crystals . . . towards nirvana and the afterlife.”2 In both the medieval pair and the contemporary sculptures, the viewer is thus invited to meditate on themes of the seen and unseen and on that which is revealed or concealed. Additionally, the viewer is invited to consider the multiple types of knowledge and knowing these mixed-media forms present, as they bridge the artificial, the natural, and the supranatural, bringing all of these into focus through radical material inclusion and stable figural form.

- 1Sally Promey, "Chalkware, Plaster, Plaster of Paris," Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), https://doi.org/doi:10.22332/con.mst.2014.1.

- 2"Kyle Montgomery Splices Crystals in Traditional Ceramic Sculptures," Juxtapoz Magazine, July 17, 2017, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/c3ef8b5d-ab43-4182-b98d-6741caa875e6.

From the Katharinenthal Visitation and Montgomery’s crystal Virgins, this nodal network expands to include Katerina Fritsch’s neon yellow sculptures of the Virgin Mary, which, like the shimmering, shifting, mineral sightlines constructed by the previous two examples, play with ideas of the intimately familiar and the uncanny. However, while those of the crystal Virgins and Visitation are produced and mediated by the fractal materiality of mineral insertions, which, as noted, lend their own subtle resonances to the narratives and figures with which they are enmeshed, distilling and refracting the mysticism of these scenes/forms and filtering them through their own hewn surfaces, Fritsch’s work leans on unbroken surface and patina to construct her questions around experiential form/presence.

Fritsch’s Madonnenfigur works were first created in 1982 and have been reproduced consistently in an unlimited edition, a mode of production that mirrors the abundant and prolific replicas of Virgin statues and figurines produced in the souvenir and commercial church supply market. As well as their inherent multiplicity and their relationship to the replica (something we also find in medieval objects),1 Fritsch’s work also echoes the limitless, boundless apparitions of the Virgin throughout time in their unlimited potentiality. Like Montgomery, Fritsch plays with the banal, repeated form of replicated souvenir Virgin sculptures, specifically, here, the Madonna of Lourdes, but while he relies on destruction/reconstruction of the original and the insertion of effacing, resurfacing geodes to ask questions of these figures and their inherent meanings and resonances, her subversion of this form exists in the shocking coloration and expansive scale given to the figures—in the case of the Virgin of Madonnenfigur (Fig. 3), this is a fluorescent, highlighter yellow.2 Other religious figures have followed the Madonnenfigur, including those composing her Figurengruppe/Group of Figures (first made in 2006–08, and cast in metal for outdoor exhibition in 2010-11), which includes the Edenic serpent, St. Michael and the Dragon, St. Katherine, and others exhibited in the garden of MOMA (Fig. 4), whose sumptuous monochrome surfaces are variously green, purple, black, and white. The Virgin, and accompanying figures, are all monotone, stripped of the visual articulation and applied detail provided by polychromy, employing a use of color that flattens their forms into monochromatic monoliths, rendering them monumental, statue-esque. These hyper-pigmented single-color sculptures are occasionally relieved by a wash of shadow, or a play of light, but exist largely in a closed circuit of color and form which both underscores and disrupts their original narratives: saturating and fixing them in these new, chromatic realities divorced from their iconic, iconographic origins.

- 1Anthony Hughes, Sculpture and Its Reproductions (London: Reaktion Books, 1997); Walter Cupperi, “Never Identical: Multiples in Pre-Modern Art,” in Multiples in Pre-Modern Art, ed. Walter Cupperi (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2013).

- 2Fritsch’s use of the Madonna of Lourdes here is significant as this particular Madonna is one that is already familiar with relocation. All around the pilgrimage site of Lourdes one can see the/this Madonna in multiples (in retail souvenir shops and carried by pilgrims, as statues or images on candles, on containers for Lourdes’ miraculous holy water, and on banners identifying various church groups on pilgrimage, etc.), thus her practice and its replicated, multiple figures are in dialogue with both the original and the replica/multiple. The authors are grateful to the anonymous readers for their discussion of Lourdes.

While Fritsch’s starting point—the reproduced and ultimately reproducible Virgin statuette—is strikingly similar to Montgomery’s use of found figures, the approach to its subversion is dramatically different, reducing the Virgin to pure form and surface, rather than enhancing and/or augmenting it with crystal (itself understood to be a heavenly material in the case of the medieval imaginary, but also to be intimately and immediately of the earth). In both cases, however, despite the difference of approach and choice of material, the effect is markedly alike. For both, the treatment of the original divorces the figure from its immediate and automatic religiosity (unlike, for example, the Katharinenthal Visitation group, where the crystal insertions deliberately heighten their ability to communicate the sacred to their viewer, revealing the Divine to the eye through the magnifying, amplifying matter of the rock crystal). That said, the undoing of the “automatic” or enmeshed sacred in these versions of Virgins—either via applied pigment, shifting scale, or the forced shattering of the figure which literally defaces the form to replace it with the crystalline geode, is always in conversation with the original (via an interwoven and significant mesh of meaning, figure, type, and trope). Indeed, both Montgomery’s and Fritsch’s Virgin variants underscore the complex waves of knowing and unknowing through material and form found in medieval objects— where the Divine is (imperfectly) revealed through the human, the earthly, and the material, either in their perpetuation of this type of epistemology, or their refutation of it. However, despite these correlations, it is notable that while the material resonances of the geodes of Montgomery’s works could be argued to deliberately enhance the mystical knowledge presented through the form, again echoing the material and spiritual complexity of the Katharinenthal group, Fritsch’s use of material takes us to a rather different set of associations. Her works, which in their repetition and use of multiples and found forms are aligned with Montgomery’s, do not necessarily emphasize the mystical and the metaphysical in their physical, material presence. Instead, through stressing the similarity to mass-produced forms commemorating the apparition of the Virgin, through evoking the souvenir/memory of the apparition and not necessarily the event itself, her figures seem to strip the Virgin of some of her spiritual patina—bringing her closer to the earth-bound and the manufactured, all the while stressing her unearthliness through the application of acid green, yellow, and interstellar violet, or nullifying black and white that envelop the sculptures.

Heath Kane’s In Brands We Trust series plays with the iconography of the Virgin through a critique of capitalism and the luxury goods market, and his treatment of the Madonna as an iconic form which is enmeshed in ideas of the hybrid and the commodified leans heavily on an intersection with another iconic female entity: Barbie.1 Now, at the moment of writing this, at the tail end of 2023, there is an epistemological fulcrum for thinking about Barbie, who, in popular culture, is very much positioned as “OUR Lady of the moment” following the release of Greta Gerwig’s movie (Fig. 7).2 The movie, much like Barbie as figure/icon/object, and much like the parallel religious use of the Madonna, is both a literal and figurative landmark which deconstructs and reconstructs understandings around socially and culturally constructed icons, a process we also find in the reuse and repurposing of figures addressed here. As a piece of cinema, it is full of visual echoes and quotations and multiplicities, its very opening a recasting of Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but it also presents a series of recognizable and replicable visual quotations across both Barbie Land and the Real World. These are based in imagined and experiential encounters that were and are and have subsequently been desired/commodified to greater or lesser extent, particularly in the various pieces of Barbie-movie-adjacent merchandise produced in the wake of the film (not the least of which are the myriad t-shirts, including from that beloved bastion of American capitalism, Target, emblazoned with “I am Kenough”). We also see this relationship to the echoic multiple in the visual quotations of real world products that are filtered into the world of the Barbies, plasticized replicas rendered into flat, dimensionless sticker-space which co-exist with generic three-dimensional ur-objects, which all construct the real qua reality. These are a stabilizing force in Barbie Land. It is, in large part, the replication of the real, through replicas of “real” objects that allows us to believe in this place as a fantastical parallel of our place, which remains firmly situated in reality. However, this process, although stabilizing, is not itself stable—the replicated simulacra of Barbie Land, with all its glossed pink ideomania, is, in turn, replicated in the here and the now (a process vastly heighted and accelerated since the movie) whereby the replica both makes and unmakes the real, and vice versa: a process of visual quotation we also find around the endless visual quotation of the Virgin.

- 1For more on the blurring of religion and popular culture see Lofton, Consuming Religion.

- 2We thank one of our anonymous readers for this line, which perfectly encapsulates the connections between Barbie and the Virgin Mary in this Constellation. Gerwig’s film is the highest grossing US box office film of 2023, and the highest grossing film with a female director ever. "The Highest Grossing Film of 2023 Worldwide BARBIE," CISION: PR Newswire, September 5, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/16607851-cce9-4799-88f0-daef4eb86755; Its release marks the first time many movie-goers chose to return to the cinema after the COVID-19 pandemic and widening home releases via internet streamers— a move that might be likened to a pilgrimage, or the collective and mobilizing desire to be in close proximity to a cult figure. Tony Maglio, "Nearly 1 Out of 4 of ‘Barbie’ Viewers Hadn’t Gone to the Movies Since COVID," IndieWire, August 11, 2023, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/91abe2f8-6978-43dd-a36d-ceb1a12d17ef.

We see this in Kane’s sculptural series of multiples, which includes two iterations of the Madonna: one made of shiny chrome, the other of white fiberglass (Figs. 8a, 8b, 8c). Each takes the form of the Miraculous Virgin, with hands outstretched. The Virgin’s head, however, has been replaced with the head of Malibu Barbie. While this beheading and reheading is significant, the monochrome harmony of the sculpture makes recognizing this as a Frankenstein form difficult at first glance.1 It is only Barbie’s round sunglasses perched atop her head, in Kane’s sculptures, that reveal the provenance of the head, and locates the limen between Malibu Barbie and the Madonna. On the other hand, Kane’s prints from the same series, which feature a monochromatic Barbie-cum-Virgin Mary figure in front of familiar brand logos, including McDonald’s and Mattel’s own Barbie logo (Figs. 9a and 9b), present a figure much more identifiable as the familiar doll, here draped in the iconography of the Virgin. In the prints, unlike the sculpture, the original brand, and the importance of the visual recognition of that brand, are intrinsic to these works. These are intriguing composites, which blend the iconography of the Virgin with those of the iconic doll to create a new form which operates in the inbetween of religion and capitalism, play and faith. One, a hot pink Barbie/Virgin on a white ground is backed with a halo-esque roundel bearing the name “Barbie” in Mattel’s hyper recognizable script, pictorializing and narrativizing her as something the viewer understands to belong to the sacred, while labeling her as Barbie-donna. The other demonstrates a similar mix of complex ideology/branding and familiar iconography, placing a blue Barbie/Virgin in front of a gilt, hand-glittered representation of the familiar “Golden Arches” logo which resonates with still other religious iconography beyond just the Madonna—it evokes a mandorla, like that of the Virgin of Guadalupe, as well as the glitter of the metallic haloes of Sienese gold-ground panel paintings of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, such as those of Simone Martini’s Annunciation with St. Margaret and St. Ansanus (Fig. 10), or Duccio di Buoninsegna’s Maestà (Fig. 11), conflating logo and logos. Moreover, in addition to this glittering sacral aura, this motif visually evokes the idea of wings, rendering her as both quasi-angelic figure and a patron saint/guardian of commerce. Such golden borders, used in religious art to demarcate the sacred, are thus also employed here to delineate the frameworks of consumption that surround these Barbie-donnas.

- 1Karen Barad, “TransMaterialities,” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21, no. 2-3 (2015): 387-422.

The compulsion to create an analogy between the Virgin Mary and Barbie is also revealed in the French artist Soasig Chamaillard’s creations, particularly Sainte Barbie (Figs. 12a and 12b)—some versions of which challenge racialized assumptions around the whitewashing of the Madonna, but some of which don’t—presenting a spectrum of possibilities around the visual presentation of the Virgin. Chamillard positions these as seemingly interchangeable, calling into question the possibility of a post-racial consumable theology akin to that surrounding the market-driven doll, which responds to the desires of its consumer base and societal demands for diverse representation.1 This representational spectrum not only more accurately acknowledges the non-whiteness of a historical Virgin Mary, but perhaps speaks to the invention of a more broadly relatable consumable version that calls into mind the idealized Barbie Land of Greta Gerwig’s film, where, although “stereotypical Barbie” portrayed by Margot Robbie is white and blonde-haired, her fellow Barbies present a diverse utopia, a world that is outside of racism, sexism, and ableism.2 In Chamaillard's work, this position is reflected through the use of damaged religious sculptures made into something more akin to commercial toys where the possibilities of both representation and commodification are interwoven. Some of Chamaillard's sculptures use Barbie’s distinctive face to replace that of the Virgin, or position Pikachu in the arms of the Virgin Mary instead of the infant Jesus. In yet another iteration, the Miraculous Virgin bears the helmeted head of a Power Ranger, while her garments are painted in the bold flat colors of their uniforms: pink, red, blue, yellow, and green, linking back to Fritsch’s use of saturated monochrome. Although they have adopted diverse material and formal approaches to their sculptures, Kane and Chamaillard both exploit the analogy of the Virgin Mary and Barbie. Barbie, in a postmodern context, is as recognizable as the Virgin Mary. Like the Virgin, who is commonly represented as Our Lady of Lourdes, Fatima, Loreto, and Guadalupe, as the Queen of Heaven, the Star of the Sea, the Miraculous Madonna or Mother of Mercy, Barbie has many guises as well—Malibu Barbie, Working Woman Barbie, Dream Date Barbie, Mars Explorer Barbie, a multiplicity and duality explored and exploited by these works.

- 1On premodern conceptions of race, see: Geraldine Heng, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Noémie Ndiaye and Lia Markey, eds., Seeing Race Before Race: Visual Culture and the Racial Matrix in the Premodern World (ACMRS Press, 2023), http://hdl.handle.net/10079/f6d04e2a-8550-416e-a579-0338587ae3eb.

- 2For more on the plastic utopia of Barbie Land, its particular social construction and the possible relationship of consumer goods as a force for change see Kathryn Reklis, “The Barbie Conversation,” The Christian Century 140, no. 10 (2023).

This replication of form, these multiplicities of presence and presentation of the figure of Barbie and the Virgin across time, dimensionality, material, and scale, alongside the fluid dynamic between material expression and framing forms found across all the nodes of this Constellation offer a jumping off point of connectivity which allows us to think about how matter shapes meaning, and how material can affect understanding and knowing. From the crystal wombs of the Katharinenthal figures which present a mystical window to the Divine; to the hybrid figures of Montgomery’s crystal Marys which move toward an obscure eschaton, prioritizing both the fractal geode and the framing figure of the iconic Madonna, now recognized solely by her gesture and her mantle, to Fritsch’s monumental figures merging souvenir/apparition and singular/multiple, to the figures (re)made by Kane and Chamaillard which allow iconic religious figures to merge with icons of popular culture—all of these ask us to think about what we know, what we see and how we are invited to look.

The iconic status of these figures is paramount—they, as the Virgin, are both of and beyond the human and the earthly, but they, as replica, as repetition, as reconstruction, as product and production are much closer to earth. Perhaps it is this drawing closer, a phenomenon enhanced and exaggerated in many cases by the materiality of these objects, that is so beguiling. Intimacy and invitation, who is looking at whom, and who is allowed to look where is a core facet of the intercessory votive objects which are the root of these constellated objects. Control of the gaze, and access to/through the material is fundamental, but is also echoed in the later (sub)versions used for contemporary socio-political commentary on consumer culture. How we see these figures, and how we see through them is vital, both in terms of how they exist as individual works in the world, but also in terms of how they exist and communicate as replicated, cloned, multiplied, conversational sets of self and other—as explored here. After all, as Jes Fernie noted in her description of the response to Fritsch’s Madonnenfigur, displayed in the urban environment of Münster, Germany in 1987: “most adults passing the sculpture could look the Madonna in the eye,” (Fig. 13) an intimacy and mode of encounter afforded by the replica, which brings it ever closer to the (imaged and imagined) real.1

- 1"LONELY, PERSISTENT, DAMAGED, LOVED: Katharina Fritsch, Madonnenfigur, Münster, Germany, 1987," Archive of Destruction (blog), n.d., http://hdl.handle.net/10079/012f2b07-153a-4403-a757-6ac311e5ad9b.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.con.2024.1

1. Meg Bernstein and Meg Boulton, "Like a Virgin? Breaking, (un)making, and replicating the Madonna across time, space, and toy stores," Constellation, MAVCOR Journal 8, no. 1 (2024), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2024.1.

Bernstein, Meg, and Meg Boulton. "Like a Virgin? Breaking, (un)making, and replicating the Madonna across time, space, and toy stores." Constellation. MAVCOR Journal 8, no. 1 (2024), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2024.1.