Frank Graziano is the John D. MacArthur Professor Emeritus of Hispanic Studies, Connecticut College. In addition to Historic Churches of New Mexico Today, Graziano’s books from Oxford University Press include Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings in Mexico (2016) and Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America (2007). Hundreds of additional photographs from Graziano’s religion projects are available to researchers at the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, here.

Apples mounded on the altar at the Catedral Basílica de Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos, Mexico

Apples mounded on the altar at the Catedral Basílica de Nuestra Señora de San Juan de los Lagos, Mexico

Roadside shrine to Difunta Correa between Salta and Cachi, Argentina

Roadside shrine to Difunta Correa between Salta and Cachi, Argentina

Toy and stuffed-animal offerings at the Pedrito Sangüeso shrine in Salta, Argentina

Toy and stuffed-animal offerings at the Pedrito Sangüeso shrine in Salta, Argentina

Roadside shrine to Gaucho Gil in Vaqueros, Argentina

Roadside shrine to Gaucho Gil in Vaqueros, Argentina

Devotees rolling to Niño Fidencio’s tomb on the “Road of Penance” at the shrine in Espinazo, Mexico

Devotees rolling to Niño Fidencio’s tomb on the “Road of Penance” at the shrine in Espinazo, Mexico

Petitionary and votive texts offered to an image in Oaxaca’s Franciscan church, Mexico

Petitionary and votive texts offered to an image in Oaxaca’s Franciscan church, Mexico

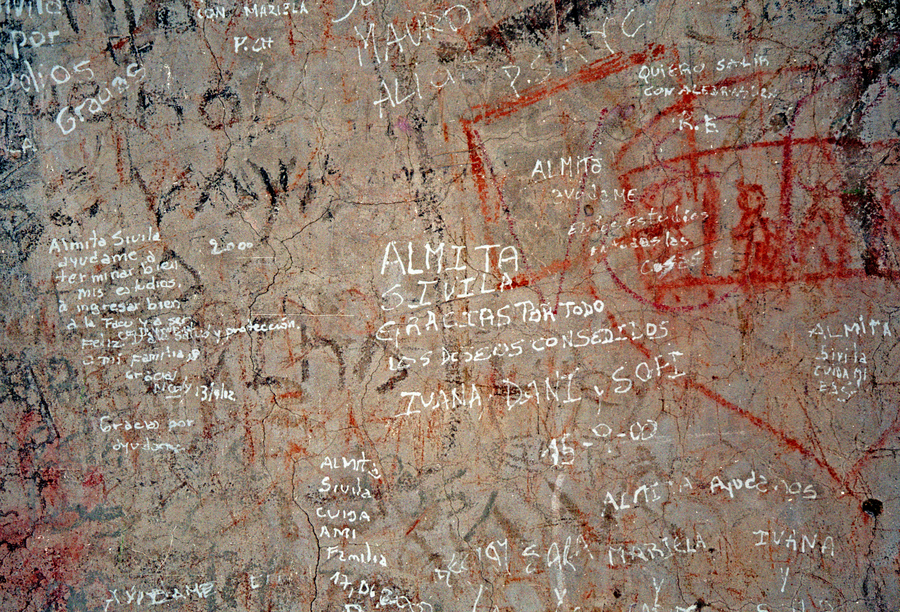

Votive graffiti at the shrine of Almita Sivila in Jujuy, Argentina

Votive graffiti at the shrine of Almita Sivila in Jujuy, Argentina

Votive plaques at the Gaucho Gil shrine in Mercedes, Argentina

Votive plaques at the Gaucho Gil shrine in Mercedes, Argentina

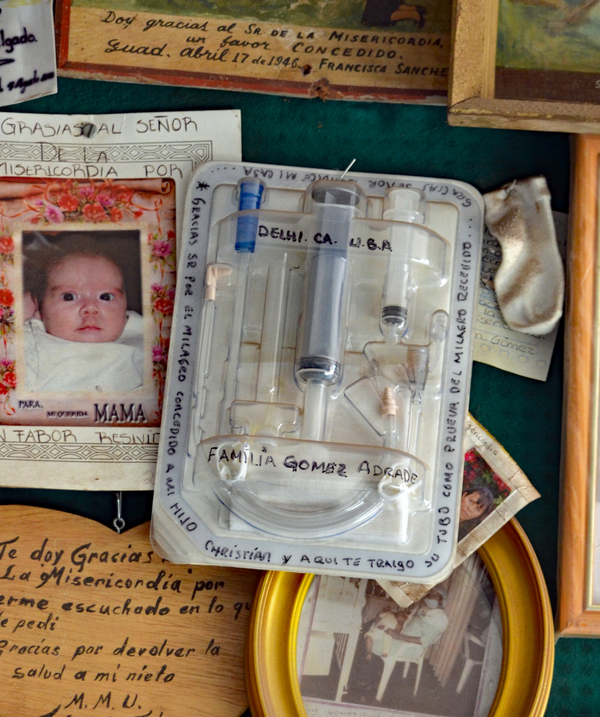

Breathing apparatus with a written message at the shrine of the Señor de la Misericordia in Tepatitlán, Mexico

Breathing apparatus with a written message at the shrine of the Señor de la Misericordia in Tepatitlán, Mexico

Offerings at the Virgen de Juquila pedimento in Santa Catarina Juquila, Mexico

Offerings at the Virgen de Juquila pedimento in Santa Catarina Juquila, Mexico

Model at the Niño del Cacahuatito shrine in Jalisco, Mexico

Model at the Niño del Cacahuatito shrine in Jalisco, Mexico

Range of milagritos—from livestock to eyes—at the chapel of the Niño del Arenal in Parácuaro, Mexico

Range of milagritos—from livestock to eyes—at the chapel of the Niño del Arenal in Parácuaro, Mexico

Relic integrated into the image of St. Felicitas in Mexico City’s cathedral, Mexico

Relic integrated into the image of St. Felicitas in Mexico City’s cathedral, Mexico

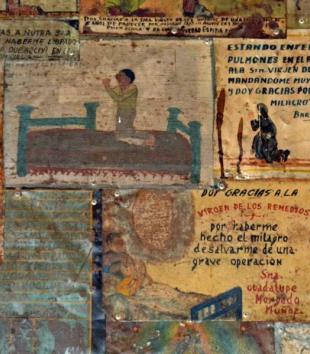

Retablos at the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in Naucalpan, Mexico

Retablos at the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in Naucalpan, Mexico

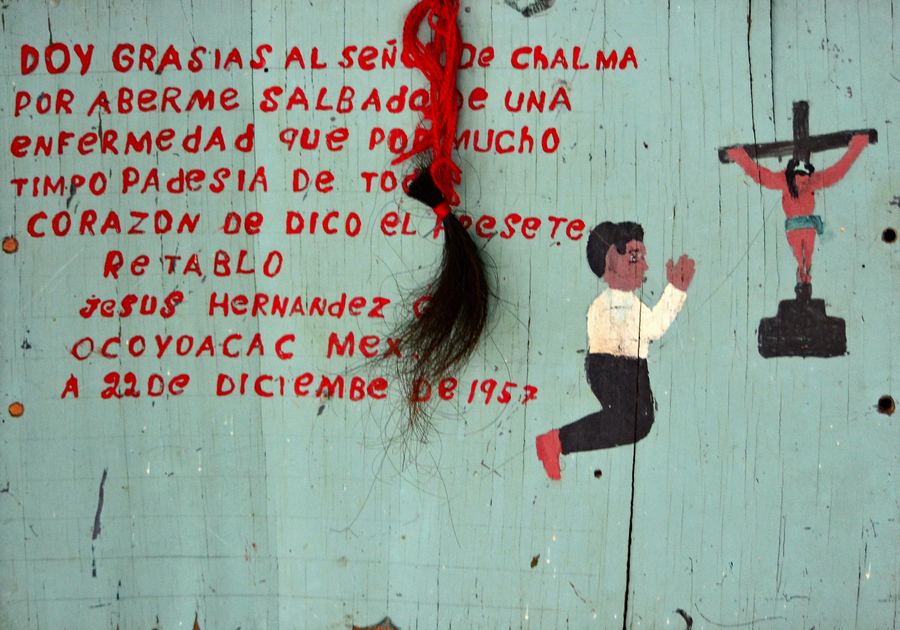

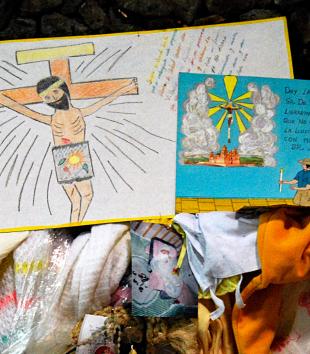

Votary-made retablo at the Señor de Chalma shrine in Malinalco, Mexico

Votary-made retablo at the Señor de Chalma shrine in Malinalco, Mexico

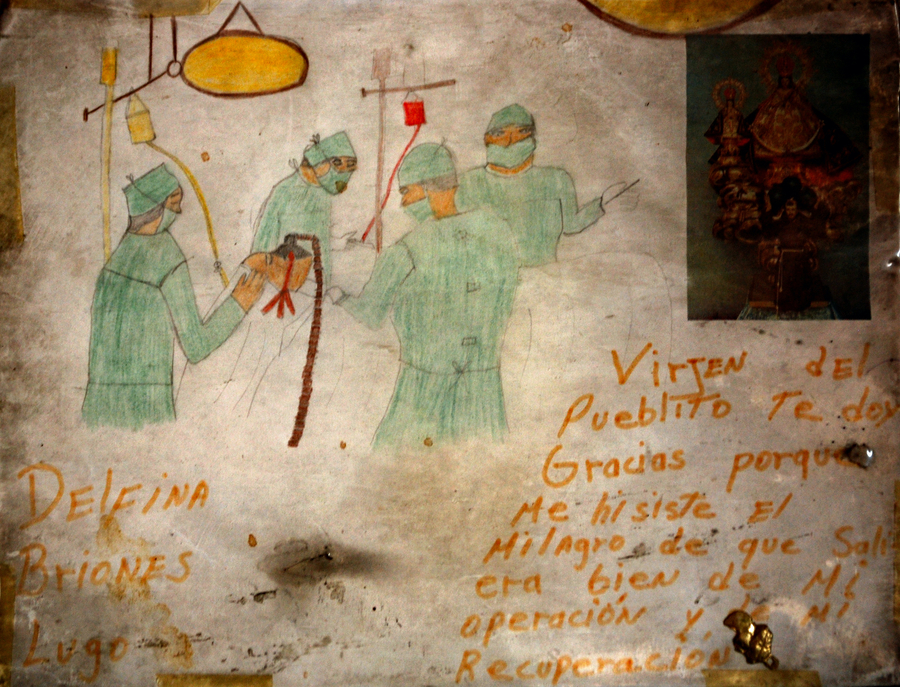

Votary-made retablo at the Virgen del Pueblito shrine in Corregidora, Mexico

Votary-made retablo at the Virgen del Pueblito shrine in Corregidora, Mexico

Collage offering to Señor de Chalma in Malinalco, Mexico

Collage offering to Señor de Chalma in Malinalco, Mexico

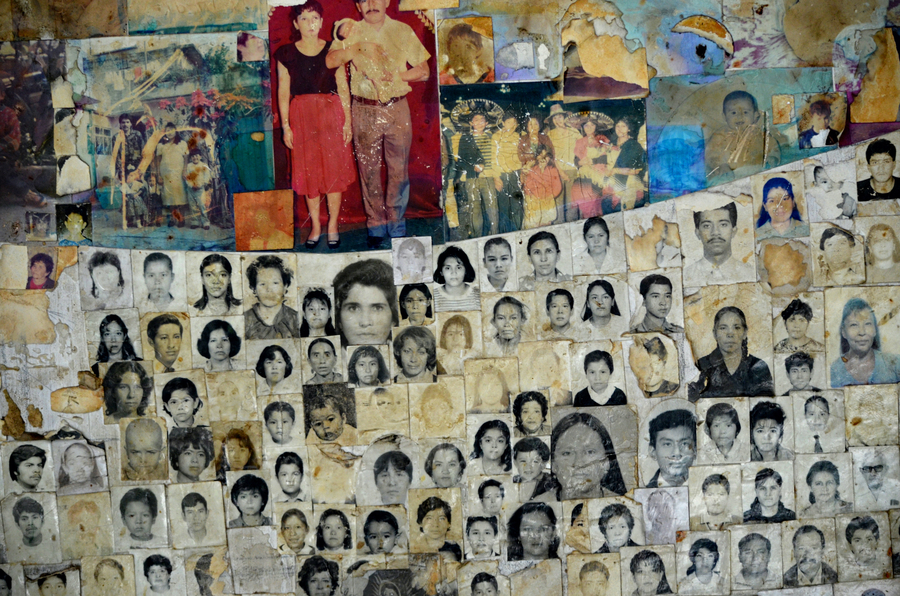

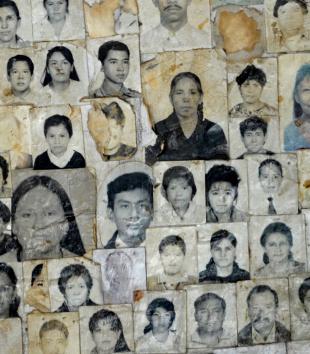

Votary photographs at the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in Naucalpan, Mexico

Votary photographs at the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Remedios in Naucalpan, Mexico

Offerings at the Santuario del Señor de Villaseca in Mineral de Cata, Mexico

Offerings at the Santuario del Señor de Villaseca in Mineral de Cata, Mexico

Braid among other offerings at the Cristo Negro de Otatitlán shrine in Otatitlán, Mexico

Braid among other offerings at the Cristo Negro de Otatitlán shrine in Otatitlán, Mexico

Devotion to folk saints and miraculous images is little concerned with salvation of the soul or with amending one’s ways to lead a more virtuous Christian life. It is rather concerned almost exclusively with petitioning sacred power for purposes that range from fulfillment of banal desires to resolution of life-threatening crises. It is a practical, goal-directed, utilitarian devotion; a survival strategy; and a resource enhancement realized through collaboration with a sacred patron. Miracles are petitioned above all for health-related matters, but also for matters concerning employment, family, pregnancy and childbirth, romantic love, education, migration, and agriculture, among others. Folk saints and miraculous images assist with passing an exam, crossing a border, healing a wound, surviving a war, getting out of prison, kicking an addiction, preventing a separation or divorce, finding lost pets and livestock, and enhancing self-esteem. Petitions thrive in social contexts characterized by deprivation and vulnerability, poor access to basic social services (including education and health care), a loss of trust in institutions and government, and a sense that it would take a miracle to survive this inhospitable world.1

Petitionary devotion is structured by an exchange that the votary proposes to a folk saint or miraculous image. The process begins with a problem or need for which the votary seeks miraculous resolution. In what is sometimes referred to as a votive or spiritual contract, the votary makes a request together with a promise to reciprocate. The promise (or vow) commits a votary to this reciprocation. The promises are conditional; the votary is not obligated unless the miracle is granted. Requests for miracles are made in oral or mental prayer (often accompanied by a petitionary offering), in written petitions, on inscribed offerings, and with symbolic miniatures (body parts, homes, livestock) that represent a desired outcome. An emotional space opens between the petition and the anticipated miracle. One waits and hopes, and as time passes one might reiterate the petition and make interim offerings or additional promises to evidence a seriousness of purpose. Miracles are contingent on faith, but faith exercised through concerted engagement and pursuit. Petitionary devotion is a way of anticipating proactively.

Votive practice in the Americas has Indigenous, Christian, and syncretic origins that contribute to the diversity of offerings, as do social class, gender, age, and region. An Indigenous villager might offer produce or feathers; an urban adolescent a schoolbook; a return migrant dollar bills; and a mother the hair of a newborn. Some of the traditional offerings to Mexico’s Cristo Negro de Otatitlán are similar to those made to a pre-contact deity worshipped in the area prior to conquest. These include corn, pumpkin seeds, eggs, and chile ancho. Also in Mexico, Indigenous devotees to the Virgen de Juquila give wheat, corn, and seeds. At some shrines, harvest offerings are made.

- 1

See, for example, Manuel M. Marzal, Tierra encantada: tratado de antropología religiosa en América Latina (Lima: Editorial Trotta, 2002), 375, where saints are sources of miracles rather than life models; Anna M. Fernández Poncela, "De la salvación a la sobrevivencia: la religiosidad popular, devotos y comerciantes," Dimensión antropológica 13, no. 36 (2006): 134, 136, and 167-168; María J. Rodríguez-Shadow and Robert D. Shadow, El pueblo del Señor: las fiestas y peregrinaciones de Chalma (Toluca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, 2000), 176-177; Yolanda Lastra, Dina Sherzer, and Joel Sherzer, Adoring the Saints: Fiestas in Central Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2009), 28; and Isabel Lagarriga Attias, "Participación religiosa: viejas y nuevas formas de reivindicación femenina en México," Alteridades 9, no. 18 (1999): 72.

In psychology, see, for example, Robert A. Emmons, "Is Spirituality an Intelligence? Motivation, Cognition, and the Psychology of Ultimate Concern," International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 10 (2000): 3, where "There is an intimate connection between religion and goals"; and Kenneth I. Pargament and June Hahn, "God and the Just World: Causal and Coping Attributions to God in Health Situations," Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 25 (1986): 203-204, where experiment subjects "turn to God more as a source of support during stress than as a moral guide or as an antidote to an unjust world," and God is "one source of reassurance, support, and encouragement" to help people endure stress.

See also Rodney Stark, "Micro Foundations of Religion: A Revised Theory," Sociological Theory 17 (1999): 268; and Hans Belting, Likeness and Presence: A History of the Image before the Era of Art, trans. Edmund Jephcott (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 6.

This Constellation is illustrated with photographs taken during fieldwork in Mexico and Argentina, but the analysis in the text applies more broadly to Spanish America at large.

The offerings that votaries promise are based on the presumption that folk saints and miraculous images, because they are like us, value what we value. It is taken for granted that they desire attention, recognition, deference, popularity; that they enjoy visits and recognize the sacrifices made on their behalf; that they are flattered by the lavish and bejeweled accoutrements, by the processions and overpopulated fiestas; and that they appreciate the offerings—candles, car parts, hair, used clothing, amateur art—made to them. When votaries and priests are asked why offerings are made publicly rather than simply giving thanks in prayer, they almost exclusively respond that offerings are testaments to a saint’s or an image’s miraculousness. By sharing the miracle with others new devotion is inspired, new petitions are made, and, in turn, miracles proliferate. The public offering is publicity.1 The highways of Argentina have votive roadside shrines dedicated to the folk saints Gaucho Gil and Difunta Correa, and these shrines likewise spread the word to passersby far from the centers of devotion. Difunta Correa and the Peruvian folk saint Sarita Colonia are also promoted when trucks that bear their names and images, like mobile billboards, travel nationwide.

- 1See André Vauchez, Sainthood in the Later Middle Ages, trans. Jean Birrell (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997) 452-453, where “the act of the donor was also a piece of propaganda.”

Votive offerings are motivated in part by a desire to inform others of a granted miracle, but also to demonstrate that a particular folk saint or miraculous image is more miraculous than others in a competitive market. In this context, a primary objective is testimonial: “In proof of the miracle”; “in testimony of such a great miracle”; “I make public testimony”; “I dedicate the present offering in testimony of her great miracles.” A probative intent is suggested too by uninscribed offerings that are made as much to document a successful petition as they are to reciprocate and give thanks. Common are official documents (visas, job appointments, admission letters, licenses), educational documents (diplomas, transcripts, grade reports), and medical documents (test results, x-rays, ultrasound images). Other documents include those pertinent to payroll, civil disputes, criminal trials, prison release, and missing persons. At some sites wedding announcements are offered.

The votary’s commitment is binding after petitioned miracles are granted. The promise or vow (voto) is followed by the votive offering (ex voto). The Spanish phrase used to describe this reciprocation, pagar la manda, denotes the idea of paying up, of canceling a debt or fulfilling an obligation, and suggests the degree to which miracle transactions are based on this-worldly protocols. Common material offerings include photographs, homemade collages, textual offerings (letters, miracles narratives, plaques), clothing, hair cuttings and braids, votive candles, flowers, and milagritos (tiny metal representational offerings). Votive gifts and practices often combine in a votive complex that might include a pilgrimage or shrine visit, prayer, and a gift accompanied by a handwritten expression of thanks, all of which together fulfill the vow. A woman helped through a difficult pregnancy might enter the shrine on her knees, present the newborn, and leave a photograph, hair cutting, and narrative of the miracle she received.1

Often there is a relationship between a folk hagiography and the offerings that are made to the saint. Folk saints who died in childhood, like miraculous images of the Christ child, are offered toys, stuffed animals, and sometimes school notebooks. In Peru, the skeletal folk saint Niño Compadrito is one of a few Peruvian images that are believed to be growing. Some devotees explain that Niño Compadrito once preferred childlike offerings—toys and candy—but now, all grown up, prefers pisco, cologne, cigarettes, and miniature casinos (he likes to gamble).2 The story of Difunta Correa’s death by dehydration while lost traveling in the desert is commemorated today by offering bottles of water. Eventually Difunta Correa became a patron of travelers, both on the road and “on the difficult roads of life,” as it is worded in a prayer, so car parts, tires, and license plates are offered. Car parts are also the principal offering to another folk saint in the region, Taxista Caputo, who was a taxi driver murdered by a passenger.

- 1I borrow the concept of votive complex from Hugo van der Velden, The Donor's Image: Gerard Loyet and the Votive Portraits of Charles the Bold, trans. Beverley Jackson (Turnhout: Brepols, 2000), 212.

- 2Regarding Niño Compadrito’s growth, see Abraham Valencia Espinoza, Religiosidad popular: el Niño Compadrito (Cuzco: Instituto Nacional de Cultura, 1983), 29. The offering preferences are from Takahiro Kato, “Historia tejida por los sueños: formación de la imagen del Niño Compadrito,” in Desde afuera y desde adentro: ensayos de etnografía e historia del Cusco y Apurímac, ed. Luis Millones, Hiroyasu Tomoeda, and Tatsuhiko Fujii (Osaka: National Museum of Ethnography, 2000), 162 and 177. Toys were also once a common offering to San La Muerte. See José Miranda Borelli, San La Muerte: un mito regional del nordeste (Resistencia, Argentina: Editorial Región, 1979), 35.

Flowers are a generic offering usually unrelated to hagiographic narratives but at some shrines—especially Sarita Colonia’s—the role of flower offerings becomes more complex. Through prolonged contact with Sarita’s tomb, bouquets absorb sacred power, as does their vase water, and these supernaturally charged flowers are gifted to visiting devotees. Such distribution serves the purposes of clearing the way for new bouquet offerings and of making Sarita’s sacred power portable. Water is also taken by some devotees to sprinkle in their homes and businesses and on their ailing body parts. One of Sarita’s sisters used flower petals and the vase water for healing rituals at the shrine. Recycling in another form occurs at the Difunta Correa shrine, where wedding gowns donated as votive offerings are lent to other devotees. The recipient enjoys the double benefit of the spared expense and of the wedding ceremony blessed by the presence of the Difunta-infused gown.

Most votaries reciprocate miracles expeditiously. A conscientious sense of urgency is intensified by fear of punishment for unfulfilled promises. Some votaries believe the consequences include death but generally the punishments are more moderate (accidents, broken bones, illness, things go badly) or entail reversal of the miracle (restored sight reverts to blindness). Cautious votaries avoid the folk saints who have reputations for harsh punishment—notably Argentina’s Difunta Correa and San La Muerte—for fear that failure to reciprocate might result in more harm than gain. Difunta Correa is described as muy pagadora (she grants miracles abundantly, delivers on her end of the bargain) but also muy cobradora (she expects what is due to her and punishes delinquent reciprocation).

Shrine visits, including pilgrimage, are in themselves and as components of votive complexes the most common form of maintaining relations with a folk saint or miraculous image. Roadside shrines and regional chapels provide opportunities for devotion without distant travel. Visits have multiple purposes: to fulfill a promise, express gratitude, make a material or textual offering, make a new petition, request forgiveness, enact faith, recharge faith, attend mass, make a confession, be in proximity of or contact with sacred power, get blessed with holy water, acquire relics, participate in fiestas, socialize with other devotees, and generally immerse in the sacred ambience. Other nonmaterial offerings include ritual dance, fiesta sponsorship, and penitential sacrifices, such as walking on one’s knees up the main aisle of a church. Especially on Good Friday, some Difunta Correa pilgrims approach the shine on their knees or crawling on their backs, even without shirts, to offer a sacrifice like their God and their saint. Similar penance is done daily on the stairway to the hilltop shrine at the complex in San Juan. Much the same occurs at the Niño Fidencio shrine in Mexico, where devotees roll in the dirt uphill from the shrine entrance to Fidencio’s tomb at the summit. The purpose of such sacrifice is to make an extraordinary gesture in reciprocation for a miracle or else to offer advance proof of commitment, of devotion, before requesting a miracle or while awaiting a response.

Fig. 5 Rolling to Niño Fidencio’s tomb on the “Road of Penance” at the shrine in Espinazo, Mexico. The materia (medium), on the far left wearing a cap, channels Fidencio’s spirit to provide sacred power to endure this sacrifice, while a mission (an organized group of devotees) provides this-worldly support and solidarity.

Less frequently votaries repay miracles with personal or social improvements (be a better husband, abstain from an undesirable behavior, reconcile with an enemy) and charitable deeds to help others in need. The last of these is particularly apparent at the shrine of Sarita Colonia, where gratitude for miracles is expressed by sharing with co-devotees. On feast days votaries bring prepared foods and other gifts to distribute among the crowd. During a two-day feast at a domestic San La Muerte shrine in Posadas the owners distribute huge quantities of food to poor neighbors waiting in long lines. Hundreds of pounds of grilled beef and side dishes are distributed, alternating every nine years with a traditional Argentine stew. The poor who attend are treated as special guests, the shrine owners explain, because they are not treated kindly elsewhere. In nineteenth-century Mexico charitable food redistribution had a different structure. Each guild offered to the Virgen de Talpa a sample of what it cultivated or fabricated, and afterward the offering was distributed to the poor. A ranchers’ guild, for example, offered beef cattle that were brought to the church door for ritual presentation and then to the main plaza for slaughter and distribution.1

Even votaries who are barely literate make an effort to textualize petitions. Their reasons for doing so underscore their preference for material immediacy and for interpersonal, humanlike relations with a folk saint or miraculous image. Petitions are written and posted at the shrine, as a sacristan put it in reference to the Cristo Negro de Otatitlán, “so that he sees them.” The same is sometimes registered in the text itself: “for you, read it my Lord.” Petitionary objects and practices are likewise intended to be seen by a saint or image.

- 1Regarding the ranchers, see Manuel Carrillo Dueñas, Historia de Nuestra Señora del Rosario de Talpa (Talpa de Allende, Mexico, 1962), 233.

Textual offerings—both petitionary and votive—range from graffiti, inscriptions on photographs and objects, and improvised notes on paper scraps to plaques, typed and framed narratives, and carefully crafted miracle testimonies. Newspapers and church bulletins provide other opportunities for textual announcement of miracles. Votive texts are also occasionally written on lengths of ribbons known as listones. This practice is used primarily in widespread Mexican devotion to Saint Charbel Makhluf, whose outstretched or bent arms gradually become covered with the ribbon petitions hanging over them. At the Gaucho Gil shrine in Mercedes ribbons are also prominent. In miraculous-image devotion, votaries use ribbons for petitions and offerings to the Señor de Chalma, including in the caves and on trees above the shrine. Ribbons also appear at the Virgen de los Remedios basilica and at the Santuario del Señor del Sacromonte in Amecameca, among other sites. Objects, notably baby clothes, are also inscribed with petitions. A small wooden truck offered by a child reads, “Take care of my dad, who is a tractor-trailer driver.” On the roof of a model house offered at Chalma the votaries wrote, “We ask that you give us the good fortune of having a home.”

Inscribed objects communicate a message with two voices, one implicit and the other explicit, a dual narration with one voice echoing off the other. The meaning of the objects and the meaning of the words engage dialectically, and the composite signifies differently and more forcefully than would the same message written on paper. “Thank you” on paper is a weak formality compared to “thank you” on a cast removed from an infant’s leg. Collage texts likewise echo off the material offerings that accompany them.

Miracles are also petitioned using uninscribed objects that represent desired acquisitions. Such representative objects are implicitly narrative—protect our cows, help my business, my infant daughter is sick. In Oaxaca miniature models of houses, children, vehicles, livestock, and other desired acquisitions are used to make petitions to the Virgen de Juquila. Devotees fabricate these at home (of wood or cardboard) or, usually, on site at a pedimento (from the verb pedir, to ask for) using the clay-rich dirt there. Wooden miniatures of houses and cars are sold for the same purpose. Petitions to the Señor de la Columna, likewise in Oaxaca, are made with plastic miniatures. Votaries also use miniature peso-bill reproductions to petition income. At the Difunta Correa complex the hillsides sloping downward from the grotto are covered with small-scale models of the homes and businesses that were acquired in response to miracle petitions.

A wide range of other implicitly narrative objects are offered to folk saints and miraculous images. Crutches, hospital wristbands, and casts represent a hardship that the votary overcame with miraculous assistance. The same is true of the shackles and manacles offered in previous centuries. Some objects represent an accomplishment: wedding gowns, musical recordings, sports jerseys from the winning team. The larger Argentine folk-saint shrines—of Difunta Correa in San Juan and Gaucho Gil in Mercedes—have museums of extraordinarily diverse offerings. All of these objects are tangible proof and narrative testimony; each tells a story about a votary and the miracle that he or she received. I used to need these crutches but thanks to you I don’t anymore, so I offer them as a token of my gratitude.

Milagritos also narrate an implicit story—my arm hurts—as they represent not merely an arm but an arm in pain, or a healed arm no longer in pain. A votive body part is not a static reproduction in miniature but rather is the material vehicle of an abstraction (pain) and an intention (petition, cure). This investment is similar to the votive purpose that makes a baby shoe more than a shoe and the sacred presence that makes a miraculous image more than an inert work of art. In Spanish America today milagritos are mass produced of inexpensive metals and are available in a range of representations beyond the more traditional body parts, sacred hearts, and kneeling votaries. Current offerings include couples, pregnant women, livestock and poultry, crops, houses, books, and vehicles, among others. At many shrines milagritos are arranged in ornamental patterns or to spell an image’s name.

The votive offerings known as retablos were originally painted on cloth or sometimes wood by professional artists and, given the expense, were offered by wealthier votaries. Retablos became affordable for popular use around 1825, when Mexican folk artists began painting on inexpensive tinplate. Retablo painters worked by commission and shared the votaries’ religious culture. The intent of the paintings was more devotional than artistic, and the works were generally unsigned. For centuries commissioned retablos were a predominant form of votive offering in Mexico but today their use is infrequent, due primarily to the availability of less expensive alternatives Some votaries follow the traditional retablo format—a painted scene over a textual narration—in homemade offerings of varying styles and qualities, but far more common are free-form votive artworks created in paint, colored pencils, markers, pastels, and crayons. Occasionally images are computer generated or made by techniques like woodburning, embossing, and crochet. At most churches the retablos that once covered walls have been discarded, stolen, or sold. A few churches, such as the Basílica de Nuestra Señora de los Dolores in Soriano, have retablo museums.1

- 1On retablos see, for example, Elin Luque Agraz, Los relatos pintados: la otra historia, exvotos mexicanos (Mexico City: Centro de Cultura Casa Lamm, 2011); Elin Luque Agraz, El arte de dar gracias: los exvotos pictóricos de María del Rosario de Talpa (Mexico City: Centro de Cultura Casa Lamm, 2014); and Jorge Durand and Douglas S. Massey, Miracles on the Border: Retablos of Mexican Migrants to the United States (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1995).

Collages of texts, images, and objects are another common substitute for traditional retablos. Many collages are framed and others are wrapped in plastic. Collages might include a drawing, photograph, and narrative text; an object associated with the miracle or its recipient together with photographs and a text; or an illustrated text accompanied by a news clipping. In simpler offerings a photograph or textual message might be pinned to an article of clothing, or diverse offerings might be enclosed together in a plastic bag. Some collages illustrate the success of a miraculous intervention with before-and-after photographs accompanied by explanatory text. The before picture shows a man in a hospital bed with disturbing wounds and tubes, and the after shows the same man as good as new. The same motif obtains in images of children before and after surgeries, and of car wrecks juxtaposed with happy votaries who walked away alive.

Unaccompanied photographs are ubiquitous. Some are inscribed on the back with a message, a petition, or an expression of gratitude. Simple snapshots show couples, families, mothers with babies, and people at work in various occupations. Head shots and document photographs suggest commended care, as do more clearly photographs of soldiers, migrants, and children. Votaries also post photographs to commemorate special occasions like weddings, first communions, quinceañeras, childbirths, baptisms, and family reunions. The happy moment is frozen and shared with others, especially the folk saint or miraculous image that made it possible. Some photographs illustrate not the votaries but the vehicles, houses, businesses, animals, and other material gains realized through petitions, or sometimes these gains with the proud votaries standing beside them. Such photographs are offered to give thanks for what is represented, to place it under a miraculous image’s care, and to publicize the image’s efficacy and the votaries’ good fortune. Other photographs, quite to the contrary, intend to arouse pity and shock the folk saint or miraculous image into action, or to evidence the tribulations suffered en route to a happy ending. Prominent in these images are wounds, skin disorders, post-surgery stitches and scars, medical procedures in progress, and seemingly moribund patients in hospital beds.

In addition to their other functions, such as gratitude and reciprocation, many offerings that are metonymies (closely associated with the votary) or synecdoches (a part of the votary that represents the whole) perpetuate one’s presence at the shrine. Clothing, particularly children’s clothing, is a common offering in this regard, as are necklaces, bracelets, and headbands. Hair offerings are highly overdetermined, because their basic votive functions are compounded by presence (the offering is part of one’s body) and again, particularly when braids are offered, by sacrifice: “I am here offering you with affection that which I so much love.”

Some braid offerings follow quinceañeras, suggesting commendation of one’s adulthood to a particular folk saint or miraculous image. Other hair and braid offerings are made after regrowth following successful chemotherapy. In special cases, which are particularly honorific, hair is donated for the wigs of miraculous images. As evidenced in votive texts, hair offerings are also made in gratitude for a variety of miracles, notably those related to health. Many braid offerings have no accompanying message and others have only the votary’s name and short texts (bless her, take care of her) or nonspecific messages: “In gratitude to the Señor de la Misericordia for hearing my prayers.”1

For men and women alike, and for parents, a hair offering is usually the culmination of a long-term process of growing and grooming. Many parents give thanks for childbirth by offering the child’s hair, sometimes the first cutting, in a manner similar to first-fruit offerings. One couple was married for eight years and could not have a child until the Cristo Negro de Otatitlán granted the miracle, “and that is why we come to give you our thanks and leave for you my son’s first hairs.” Others say that a child’s hair should be offered when he or she turns three, or at least three. An offering to Mexico’s Virgen de San Juan de los Lagos is written by a mother in the voice of a child: “In gratitude for allowing me to reach my third birthday I leave you my hair.” Another offering to the same image is also written in the voice of a child, in this case a four-year-old girl who was cured of an eye orbit deformity. “I will enter your shrine in my blue dress, which I will give to you with my hair that for four years I took care of for you.” The ancient Greeks referred to this process as “growing hair for the god.” Some parents offer their own hair rather than the child’s. In gratitude for curing an infant daughter’s respiratory problems, a mother offered to the Virgen de Talpa a collage with a hospital photograph, a substantial braid, and a text that included, “I thank you and I’m bringing my daughter to you as I promised . . . and also a piece of my hair.”2

The first quoted passage is in José Velasco Toro, De la historia al mito: mentalidad y culto en el Santuario de Otatitlán (Veracruz: Instituto Veracruzano de Cultura, 2000), 150. Regarding first-fruit offerings in a related context, see Hugo G. Nutini, Todos Santos in Rural Tlaxcala: A Syncretic, Expressive, and Symbolic Analysis of the Cult of the Dead (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 181, where first fruits are “an entreaty and a reminder to the dead to watch over the crops.”

The quoted Greek phrase is from David D. Leitao, “Adolescent Hair-Growing and Hair-Cutting Rituals in Ancient Greece: A Sociological Approach,” in Initiation in Ancient Greek Rituals and Narratives: New Critical Perspectives, ed. David Dodd and Christopher A. Faraone (London: Routledge, 2003), 111.

Votaries also make umbilical offerings in gratitude for childbirth, especially in Chalma. Regarding umbilical cuttings see Alicia M. Barabas, Dones, duenos y santos: ensayo sobre religiones en Oaxaca (Mexico City: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2006), 175; and Victor Turner and Edith Turner, Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture: Anthropological Perspectives (New York: Columbia University Press, 1978), where plate 5 (see page 55) shows strips of cloth, some with umbilical cuttings, on exposed tree roots on a pilgrimage route. See also Paul Cassar, “Medical Votive Offerings in the Maltese Islands,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland 94, no. 1 (1964): 2, where votive offerings include kidney stones, swallowed objects, and other things removed from organs.

Votive offerings are multiply efficacious: they fulfill promises, pay debts, express gratitude, bear witness, document and memorialize, strengthen faith, and mediate discursive exchanges between votaries. Some offerings tend more to one function than another, and many combine functions in various configurations. A collection of votive offerings relates a history of misfortunes, but the suffering, despair, vulnerability, and tragedy are ultimately redirected toward the happy endings afforded by miraculous intervention. Unlike the iconography of Christ, which fosters toleration of suffering through empathetic identification, petitionary devotion subordinates suffering to the miracle of alleviation. Votive offering transforms a community’s trials into success stories conducive to perseverance through faith. The offerings also aspire to a sense of permanence or at least longevity, to memorializing the fleeting miraculous moment in an enduring document or object. Such phrases as “for perpetual memory” and “I leave the miracle painted for memory” evidence an intent to objectify the miracle so that it will endure and be reactivated, in effect, by the perception of devotees who view its representation. A miracle remedies the out-of-control situation, the offering objectifies a sense of closure, and one’s faith in the image’s ongoing vigilance makes the remedy seem permanent. The votive offering serves as a kind of insurance, or assurance, that the positive change will endure.2

See Karina Jazmín Juárez Ramírez, Exvotos retablitos: el arte de los milagros (Guanajuato, Mexico: Centro de las Artes de Guanajuato and Ediciones Rana, 2008), 24; and Viktor Gecas, “The Social Psychology of Self-Efficacy,” Annual Review of Sociology 15 (1989): 310

For overviews of votive offerings in other regions and periods, see Francisco de Florencia, Origen de los dos celebres santuarios de la Nueva Galicia, obispado de Guadalaxara, en la America septentrional (Zapopan, Mexico: Amate Editorial, 2001), 133-137; van der Velden, Donor's Image, 213-222; LiDonnici, Epidaurian Miracle Inscriptions, 42-44; and Mercedes Cano Herrera, “Exvotos y promesas en Castilla y León,” La religiosidad popular, vol. 3, Hermandades, romerías y santuarios, ed. Carlos Alvarez Santaló, Maria Jesús Buxó i Rey, Salvador Rodríguez Becerra (Barcelona: Editorial Anthropos; Sevilla: Fundación Machado, 1989), 392-395.

- 1For other examples of hair and braid offerings, see George M. Foster, Tzintzuntzan: Mexican Peasants in a Changing World (New York: Elsevier-New York, 1979), 235-236; Luis Mario Schneider, Cristos, Santos y Vírgenes: santuarios y devociones en México (Mexico City: Grupo Editorial Planeta, 1995), 20; and Frank S. Edwards, A Campaign in New Mexico with Colonel Doniphan (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1996), 24, where a mid-nineteenth-century narrative of a military campaign notes what appear to be hair offerings in Santa Fe. For examples in other regions and periods, see G. J. Tassie, “Hair-Offerings: An Enigmatic Egyptian Custom,” Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 7 (1996): 64; Lynn R. LiDonnici, The Epidaurian Miracle Incriptions: Text, Translation and Commentary (Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995), 41 and 44; and R. C. Finucane, The Rescue of the Innocents: Endangered Children in Medieval Miracles (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1997), 14.

- 2a2b

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.con.2023.1

1. Frank Graziano, "Petitionary Devotion: Folk Saints and Miraculous Images in Spanish America," Constellation, MAVCOR Journal 7, no. 1 (2023), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2023.1.

Graziano, Frank. "Petitionary Devotion: Folk Saints and Miraculous Images in Spanish America." Constellation. MAVCOR Journal 7, no. 1 (2023), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2023.1.