Paul Christopher Johnson is Professor of History and the Doctoral Program in Anthropology and History at the University of Michigan: He is Editor of the journal Comparative Studies in Society and History and author of Secrets, Gossip and Gods: The Transformation of Brazilian Candomblé (Oxford, 2002), Diaspora Conversions: Black Carib Religion and the Recovery of Africa (California, 2007) and, most recently, Automatic Religion: Nearhuman Agents of Brazil and France (Chicago, 2021).

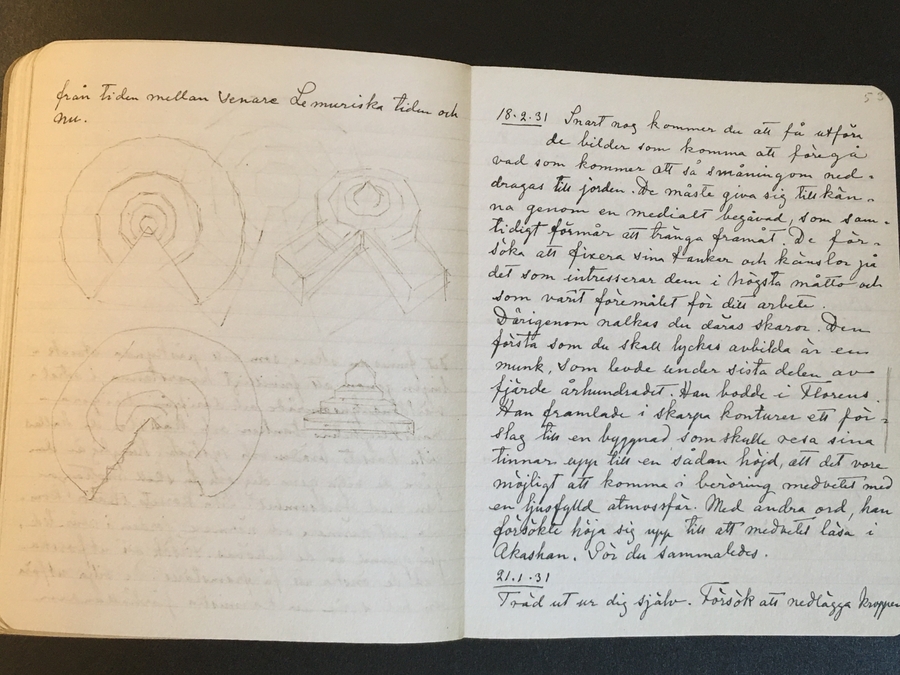

In 1904, a spirit named Gregor told the artist Hilma af Klint that she would be asked to design a temple to house a series of paintings. By 1915, she completed the 193 paintings for the Temple. Af Klint painted automatically in response to her spirit guides, a kind of visual dictation. She never built the Temple that could have permanently housed the paintings in Sweden. But she conceptualized the structure—at once physical and metaphysical—and, in her notebook of 1930-31, made sketches for its design. Her vision of a spiritual-aesthetic space presaged analogous projects actually brought to completion, from Rudolf Steiner’s Goetheanum to the Guggenheim Museum in New York, first pitched to Frank Lloyd Wright in 1943 as “a temple of spirit,” to the Rothko Chapel in Houston of 1971, introduced at its dedication as a “sacred place, open to all, every day.”1 So-called sacred space has historically been made through consecration and repeated ritual use. Other venues are venerated as scenes of the feats of founders. Still others impress as natural wonders and sublime anomalies. But what about planned sacred spaces, considered in terms of materials, craft, labor, and design? Through Af Klint’s journal entries and sketches, we can shift analyses of sacred space from the guise of transcendent force that simply “appears,” in the phenomenological nomenclature, and instead approach it as technique.

- 1Annie Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko: Toward the Light in the Chapel (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2016), 190.

As Af Klint described and drew her Temple, it should be a circular building. Three levels would be composed of stacked rings, tapering upward, connected by a four-story central tower. Distinct series of paintings would occupy each level: “Physical Pictures” on the ground floor, “the Ten Largest” on the second floor, along with a library; the “Altarpieces” at the top. Visitors would perambulate the round structure, progressing inward from periphery to center and upward on the spiral path, along a spiritual trail established by the paintings. Outward to inward, below to above; like a Kabyle house or an Aztec pyramid, or a day in prefab socialist gray, visitors would be transformed as they walked, spiraling and mounting, forged by the space they traverse. The entire construction should be “imbued with a certain power and calm,” which would then also fill the bodies of visitors. This would work not only through direction, shape, and progression, but also through color. Color and shape did not symbolize the cosmos, they mediated and channeled it; they helped to make it.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.23

1. Paul C. Johnson, "Hilma af Klint's Temple for the Paintings," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.23.

Johnson, Paul C. "Hilma af Klint's Temple for the Paintings." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.23.