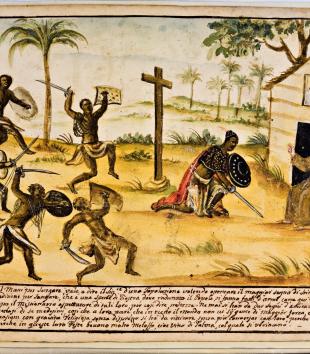

In the first half of the twentieth century and much of the last half of the nineteenth, seemingly ubiquitous representations of light-complexioned religious figures, saintly and divine, in two and three dimensions, as pictures and figural sculptures, gazed down from altars, walls, shelves, and other sorts of pedestals. Visibly claiming to regulate the prescribed Christian imitation of the biblical figures they represented, these statues populated domestic spaces, churches, and missions fields, and implied that looking like Jesus or Mary or John might be more “natural” or “complete” for some than for others. Ella Watson, a Washington DC member of the Reverend Vondell Verbycke Gassaway’s Protestant, predominantly African American, Verbycke Spiritual Church, constructed a bedroom shrine using a large rosary and six chalkware statues of the sort easily acquired from a Catholic church supply store.1

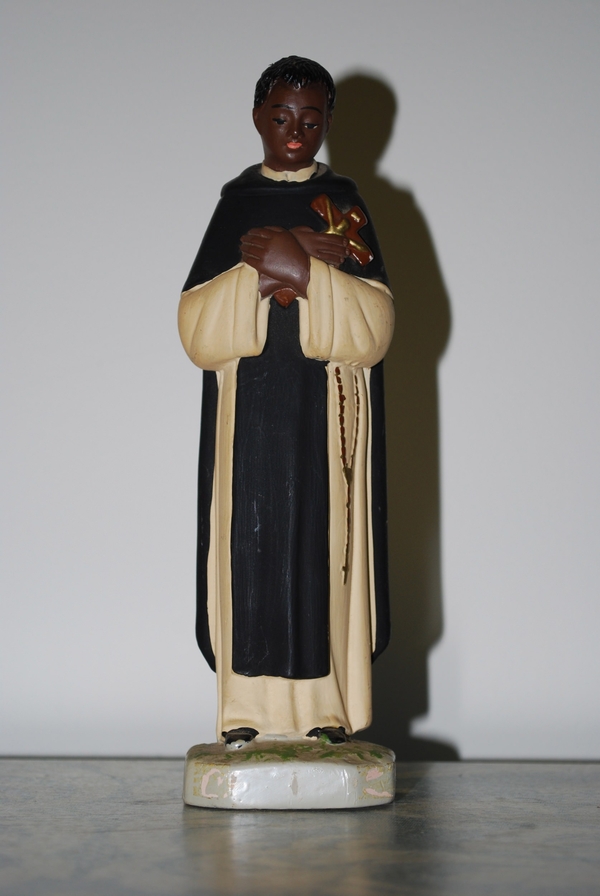

In this photograph (Fig. 1) by Gordon Parks (who was also African American), the Protestant Watson, seen in her dresser mirror, reads from the bible that she has just taken up from its usual place on this domestic altar (complete with flowers, candles, crucifix, and two small elephants). A sacred heart blessing hangs on the wall adjacent to the bureau, to its left in the photograph. Of the eleven pictorial personages visible in her display (from left to right: [1] Jesus of the sacred heart in the print on the wall, [2] St. Therese of Lisieux (Fig. 2), [3] Our Lady of Lourdes, [4] Joseph holding the [5] small child Jesus (Fig. 3), [6] the crucified body of Christ on the rosary that hangs down the center of the mirror, [7] the statue of St. Martin of Porres (Fig. 4), [8] the one of St. Anthony of Padua also holding [9] the Christ child, [10] the body of Jesus on the small standing crucifix, and [11] Our Lady of Grace), only one, St. Martin of Porres, has comparatively dark skin.2 Compounding this numerics of complexion, the dresser mirror doubles four of the statues, including St. Martin, but Watson appears only once, as reflection.

The language and media of artistic production are by no means ideologically neutral in social and cultural conditions of racism obsessed with skin color. Each of Watson’s six full-figure statues (two of them representing two holy persons each) was made of chalkware. The use of this common plaster medium replicated the “color” of marble, alabaster, and porcelain, and further instantiated whiteness as the normative material “appearance” of Christianity. While some individuals, beginning in the nineteenth century, worked to create alternative visualizations, most church supply houses produced objects that operated according to a racial material economy that constrained memory and imagination as well as evoking them. Visual religious practices replicated and instantiated dominant race and gender politics. This was especially clear in material evangelization and missionary activity, and unmistakably inscribed in domestic pieties as well.

Notes

Notes

1. See Colleen McDannell, Picturing Faith: Photography and the Great Depression (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004), 260.

2. Importantly, Gassaway also founded a “school of metaphysical study” that he named St. Martin’s Spiritual Center (ibid), likely after the dark-complexioned St. Martin of Porres; St. Martin’s Spiritual Center held its meetings in the church building. Despite this recognition of St. Martin, and the presence in the church of a modestly-scaled chalkware statue of the dark-skinned saint, almost all of the church’s other, and larger, religious statues had white features, a characteristic of the statuary available in contemporary church supply catalogs. The statues in Verbycke Spiritual Church represented a selection of saints that were larger in scale but otherwise similar to the ones on Watson’s dresser.

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.45

1. Sally M. Promey, "Gordon Parks, Dresser in the bedroom of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.45

Promey, Sally M. "Gordon Parks, Dresser in the bedroom of Mrs. Ella Watson, a government charwoman." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.45