Rachel McBride Lindsey is a scholar of religion and visual culture and teaches in the Department of Theological Studies at Saint Louis University. Lindsey's scholarship focuses on material and visual cultures of religion, particularly in relation to visual regimes of race and nation, and traverses disciplinary frameworks of visual studies, American studies, and religious studies. Her first book is A Communion of Shadows: Religion and Photography in Nineteenth-Century America (University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

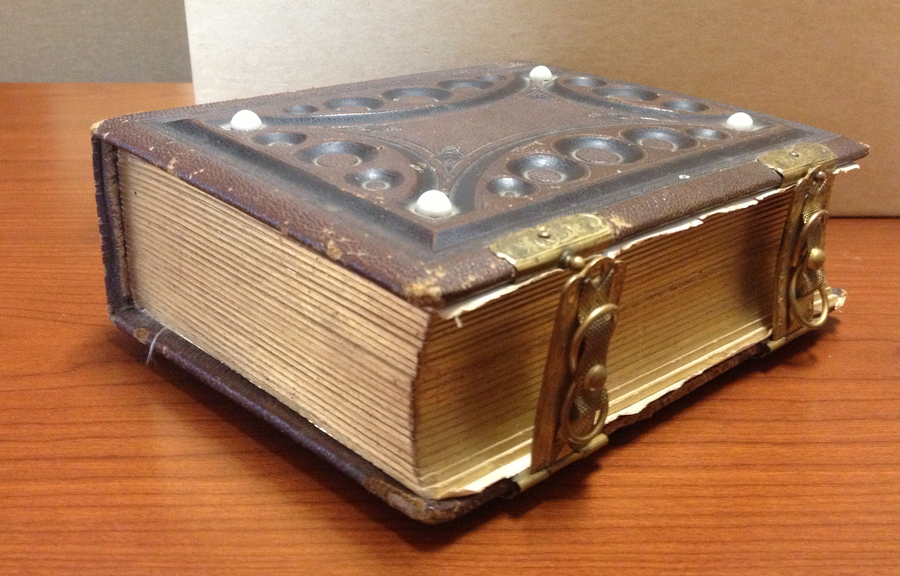

At times something entirely ordinary can reveal something extraordinary. In its embossed leather binding, brass clasps, and gilt-edged pages, this photograph album is identical to thousands upon thousands of others that flooded American marketplaces in the 1860s and early 1870s. This one is small, about six inches long, four inches wide, and two inches thick, and opens by unfastening two bronze clasps. There are no obvious signs that this artifact was in any sense religious. The leather binding is embossed but there are no crosses or angels or bible verses. And yet the sensorial experience of the album demonstrates one of many ways in which nineteenth-century visual habits had much to do with photography’s courtship of religious imaginary. Even as photographic technology was lauded as an emblem of scientific progress, practices of beholding—of touching, seeing, deciphering, remembering—were rooted in visual habits that muddled the lines between progress and tradition, religion and science, sacred and secular. What photograph albums teach us about nineteenth-century viewing habits is that the reach of religion extended beyond compositionally “religious” subjects. Modes of beholding were often forms of religious practice that did not require a regulated rift between sacred and secular.

The album is now a gallery of ghosts. Even though the likenesses are remarkably crisp, the distinct lineaments of each portrait mock the dearth of identifying information about the sitters. Portraits in the mid-nineteenth century were commonly called “shadows,” a term that acquires added nuance when the image is all that remains. We see them clearly but cannot know them. I found the album through an antiques retailer in Massachusetts who purchased it at a local estate sale. It lacks signatures, has no salutatory inscription, and only two likenesses were identified. We will come back to those. But even if its provenance has become clouded and its recorded history is mute, the album itself presents some clues about its history and the history of those who have beheld it.

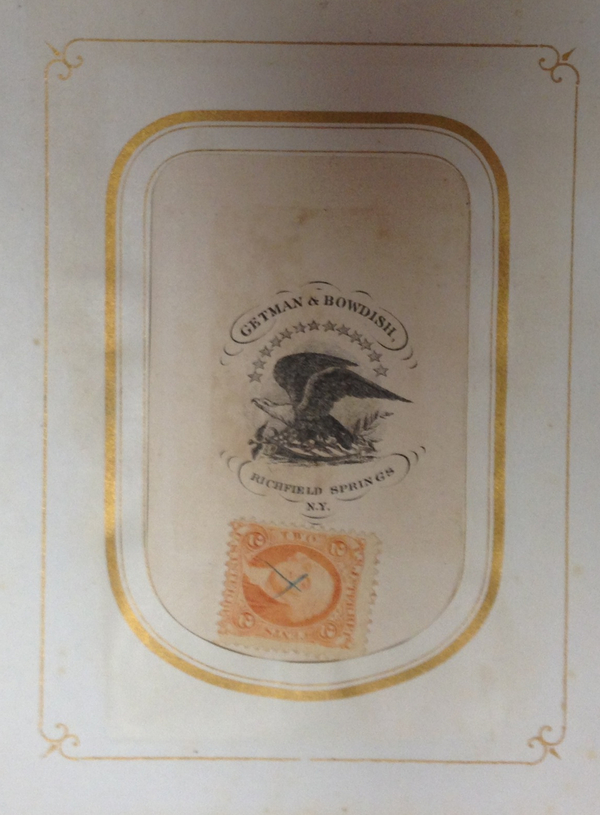

When I first approached the album, all of the small, card-sized photographs were snug in their designated apertures. Cautiously, haltingly, mournfully, I disturbed a few in search of an interpretive toehold. Several of the prints inside the album have the markings of the Getman & Bowdish studio of Richfield Springs, New York. An 1868 map of the city identifies N.S. Bowdish as the proprietor of Bowdish’s Photograph Gallery on Main Street. An 1870 federal census schedule confirms that Bowdish was a “photographer” of some means. A decade earlier one Nelson Bowdish had been a “melodian builder,” a craftsman specializing in small reed organs manufactured for small churches and private homes. If N.S. was Nelson, Bowdish would have been among the thousands of entrepreneurs who took up trade in likenesses in the earliest days of print photography. We can be reasonably certain that the album itself dates from this period through other evidence. One of the prints has a canceled two-cent tax stamp. Since these taxes were only levied between 1862 and 1865, the album was likely compiled with photographs made in the early 1860s, a period that coincides with the popularization of card-sized paper prints. In other words, this album represents the height of new visual technology in the mid-nineteenth century.

If we can begin to make out the shapes of the photographers, however vague, standing behind the camera, the people who sat in Bowdish’s “photograph posing chair”—a device he patented in 1871 to the delight of “the photographic fraternity”—remain lost in the shadows.

Commonplace objects like this album often hide behind a veil of familiarity, so much so that their ordinariness renders them invisible. More than that, the album might be handily dismissed as merely a place where artifacts are stored rather than an artifact on its own right. The album, however, beckons its beholders to acknowledge its profound materiality and its unmistakable presence. Before I can “look at” the pictures, I have to grasp the album. I feel dimpled leather and embossed patterns and pause at the album’s heft. Its size, small enough to cradle in my hands, prompts an expectation of intimacy. The cool metal and whispered click of the clasps recall the clasps of the period’s family bibles. These are no ordinary books. Each page presents one face. To me they are anonymous, despite my efforts to identify them. To previous beholders they were lovers, mothers, fathers, children, siblings, friends. Framed within the album’s fifty pages are twenty-four women, twenty-one men, two prints of children individually, and one print of a pair of children. Forty-eight photographs. And two other relics.

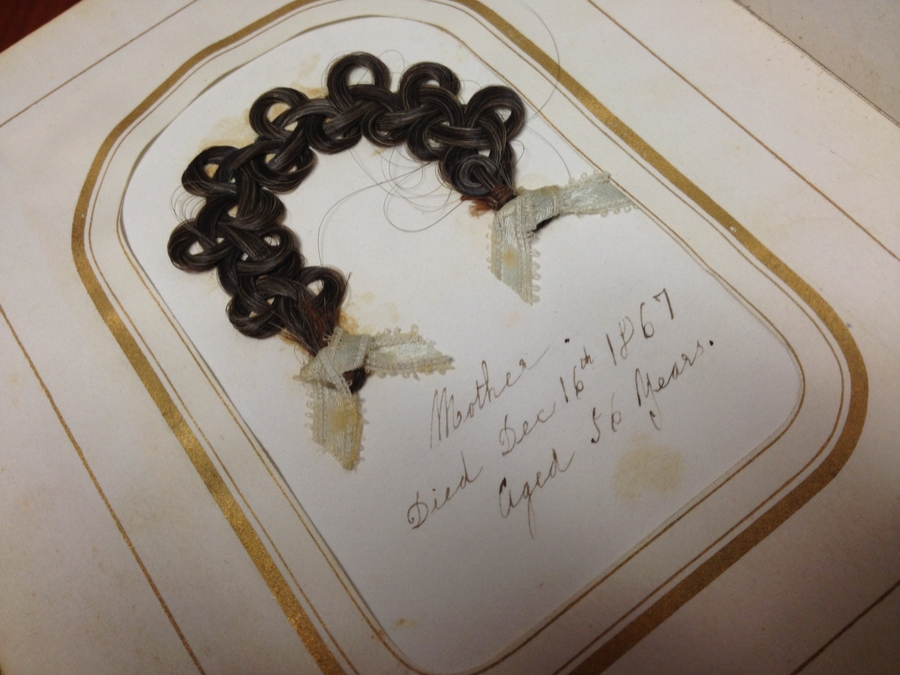

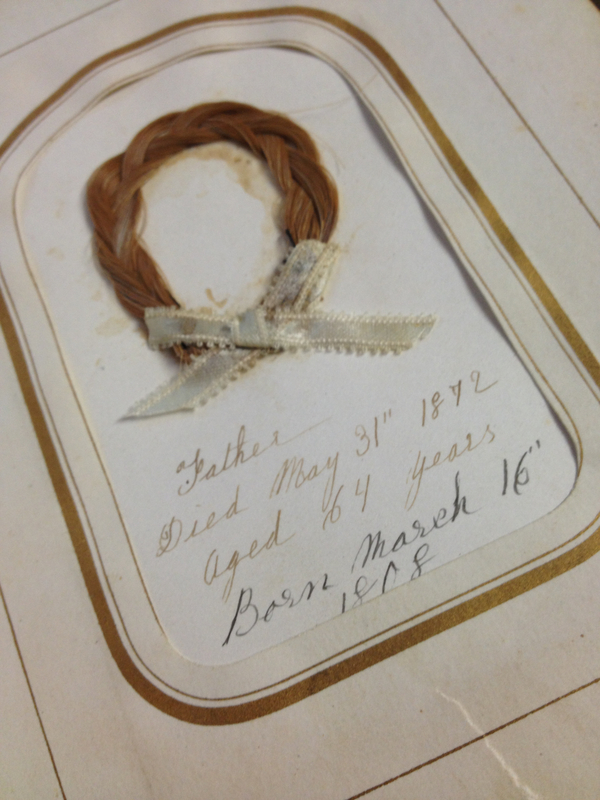

The primary reason I acquired this particular album was because, tucked inside the gallery of likenesses, it preserves two pieces of carefully worked hair arranged as if to frame absent faces. These are the only pages in the album that have any textual commentary: “Mother Died Dec 16'' 1867 Aged 56 Years” and “Father Died May 31'' 1872 Aged 64 years Born March 16'' 1808.” For nineteenth-century beholders, photographs and hair served a similar memorial operation. For more than half a century before the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, hair had been worked into patterns and painted miniatures as a token of affection as well as memento mori. In the 1840s and 1850s, tucks of hair were frequently preserved in daguerreotype cases, either behind the mirrored likenesses, in a kind of miniature tomb, or in more visible positions. Photograph albums like this one trained beholders how to curate, see, and interpret portraits—to anticipate compositional arrangements. The hair in this album is arranged within this compositional framework of portraiture; it no longer evokes life generally, but a face specifically, even if that face has been lost to time. To modern beholders the hair is quite certainly the punctum of the album; it is what grabs beholders and elicits reflection on the ordinary. But among the first beholders of the album, what was remarkable was that photographs had become a corporeal relic, a vehicle that connected the departed and the bereaved and that enabled the past to live into the present. The album demonstrates a moment in time when hair and photographs were entangled mechanisms of memory. Today we might find ourselves recoiling from an accidental brush with antiquated hair. And yet we continue to cherish photographs for their ability to nurture connections with those who populate the photographic image. This album testifies to a moment when photographs became living relics, when the divide between substance and shadow was bridged, when memory of the past punctured the beholder’s present. This way of understanding photography as not merely a document of the past but as a relic that conditioned continuous presence had profound consequences not only in portraiture but in the American religious imaginary as well. From portraits that testified to celestial reunion to photographs of Palestine that enabled American beholders to witness the Holy Land of the Bible, the visual habits that transformed photographs into relics intersected and shaped religious imaginaries throughout the nineteenth century.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.39

1. Rachel McBride Lindsey, "Carte de visite Photograph Album," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.39

Lindsey, Rachel McBride. "Carte de visite Photograph Album." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.39