Rolando Estévez Jordán, a visual artist, and Alfredo Zaldívar, a poet, co-founded Cuba’s Ediciones Vigía (Watchtower Editions) in 1985 to create an open forum for writers, musicians, and artists.1 They began by creating single-sheet flyers to advertise meetings, but their venture soon evolved into a publishing house that now produces limited edition handmade books and journals. Typically designed by Estévez and assembled by artisans, the publications are celebrated for the sophisticated interaction of word and image, the use of repurposed and recycled materials, the presence of flaps, pop-up illustrations, pull-down scrolls, and movable parts, and the active and multi-sensory engagement they demand of reader-viewers.

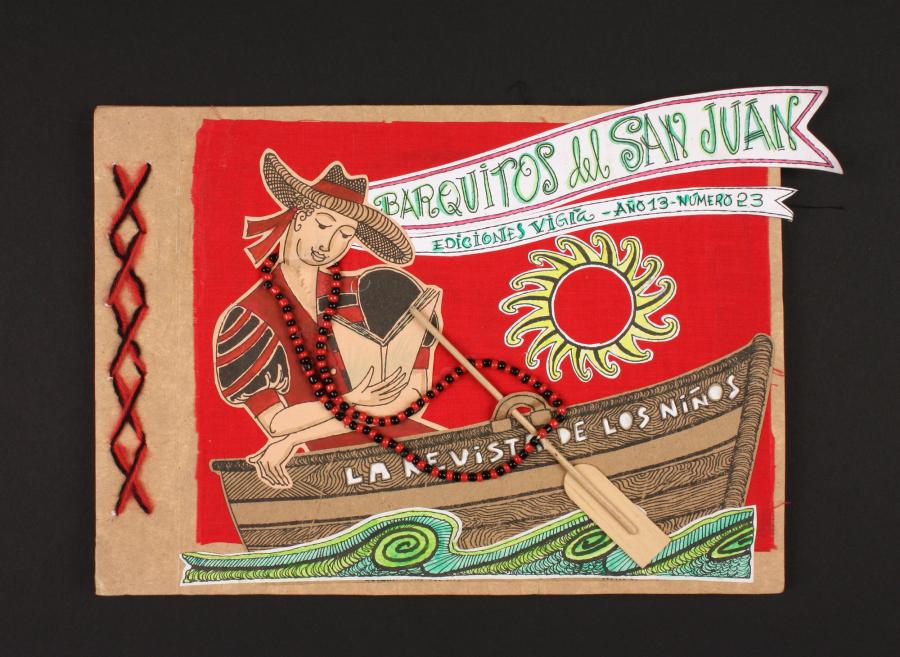

A 2007 issue of Vigía’s magazine for young people, Barquitos del San Juan, features a young man reclining in a rowboat wearing a red and black striped tunic with exaggerated short sleeves, one striped, the other solid. The young man’s fine facial features suggest that he is Afro Cuban and his attire, recalling that of a medieval jester, identifies him as Elegua, one of the most important orishas2 in la regla de ocho (the rule of eight), a religious worldview and practice popularly known as Santería.3 Elegua is the god of the threshold and the crossroads, a paradoxical figure who embodies openings and closings, life and death, light and dark, day and night. He is also irascible, testing people’s faith, playing childlike pranks, and tripping up unsuspecting travellers.4

The use of Elegua for a children’s magazine is particularly appropriate since the orisha’s most popular Roman Catholic counterpart is El Santo Niño de Atocha (the Holy Child of Atocha).5 The two share similar mythologies—they guide and protect travellers—and iconographic features— they are depicted as children with wide-brimmed hats, ornate and often ruffled clothing, and staffs. In addition to serving as a point of identification with young readers, Elegua’s reputation as a mischievous trickster emphasizes the playfulness and humor of many of the poems, riddles, and short stories that fill the issue’s pages.

Estevéz contributes to the issue’s focus on Elegua by employing the orisha’s ceremonial roles and familiar attributes to shape the reader-viewer’s interaction with the magazine.6 Elegua, the first orisha to be invoked at initiation rituals, summons the reader-viewer into the issue through his appearance on the cover. Just as the orisha stations himself at entryways and unlocks doors, so he introduces each new section of the magazine. Finally, Elegua’s constant vigilance leads him to peak out from behind the outer edge of each manuscript page, waiting for an opportunity to test the reader-viewer and offer alternatives that might bring good fortune but could also result in adversity.

By using Elegua as a ritual evocation, as a structural element, and as a repeating motif, Estevéz links critical reading and viewing to Elegua’s watchfulness and to the vigilance he elicits in believers. Estevéz intimates that this issue of the magazine “hosts” Elegua, as well as the chicanery he embodies, by christening the boat on the cover “La Revista de Niños.” He more broadly identifies the press with Elegua on the back cover, where the orisha lies sleeping in a rowboat. Here the boat is named “Ediciones Vigía Mantanzas Cuba,” and the orisha is juxtaposed with the press’s symbol, the oil lamp. In this way, Estevéz avows that both Elegua and Vigía are perpetually vigilant; they provide a light and guide the way. Neither guarantees, however, that the route they suggest is the right one to take. Like practioners of Santería, reader-viewers of this issue of Barquitos del San Juan should be wary; Elegua is not always a trustworthy guide.

Estevéz’s equation of Vigía and Elegua underscores the continuing impact of the press’s origins in the 1980s on its convictions regarding art’s cultural work. While Cuba’s “stagnation period” in the 1970s was marked by the marginalization of artists, the cultural renaissance of the 1980s was celebrated for the production of art that searched for Cuban and Afro-Cuban identities, embraced popular culture, engaged in social critique, and challenged the production-consumption model of art.7 Vigía continues to call its reader-viewers to be critical, yet contribute to Revolutionary ideals, to be independent, yet participate in community, to be global, but attend to national concerns, and to be attentive, always, to the possibilities that can lead alternately to repression or to freedom.

Notes

Notes

1. On Ediciones Vigía, see María Eugenia Alegría, Rolando Estévez, and Alfredo Zaldívar, “Vigía: The Endless Publications of Matanzas” in Michigan Quarterly Review, ed. Ruth Behar and Juan Leon, vol. 33, no. 4 (Fall 1994): 828-835; Linda S. Howe, Cuban Artists’ Books and Prints / Libros y Grabados de Artistas Cubanos: 1985-2008 (Winston-Salem, NC: The Cuba Project, Wake Forest University, 2009); and Kim Nochi, “Ediciones Vigía Books in Art and Cultural History,” MA Thesis, University of Missouri, 2012.

2. Orishas, most often interpreted as spiritual beings or dieties, are emissaries to the Yoruba supreme being, Olodumare. Like saints in Roman Catholicism, they are dramatic figures whose legends are encapsulated in iconographies familiar to initiates. Philosophy and religion scholar Nathaniel Samuel Murrell writes that “the most obvious and common creole feature of Yoruba in Cuba is the paralleling of African divinities with Catholic saints, represented by chromolithographs and New World rituals.” Murrell, Afro-Caribbean Religions: An Introduction to Their Historical, Cultural, and Sacred Traditions (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2009), 101.

3. Santería is a transcultural religious system that combines the Yoruba worldview that African slaves brought with them to the New World with the Spanish Catholicism imposed upon them when they arrived in Cuba. On Santería, see Joseph M. Murphy, Santería: African Spirits in America (Beacon Press, 1993) and Working the Spirit: Ceremonies of the Africa Diaspora (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995); David Brown, Santería Enthroned: Art, Ritual, and Innovation in an Afro-Cuban Religion (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003); and Murrell, Afro-Caribbean Religions).

4. This summary of Elegua’s characteristics comes from: Miguel “Willie” Ramos, “Afro Cuban Worship,” in Santería Aesthetics in Contemporary American Art, ed. Arturo Lindsay (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1996): 62; and Brown, Santería Enthroned, 173.

5. Although Elegua is also associated with St. Anthony of Padua, his association with El Niño de Atocha is more common.

6. The magazine opens with a short history and description of Elegua by Agustina Ponce, the director of Barquitos del San Juan. It concludes with a pull-out poem by Míriam Rodríguez entitled Guerreros (Warriors) which characterizes the four orishas that are received first by Santería initiates: Elegua, Oggún, Ochosi, and Ozun.

7. The contemporary Cuban art critic, Gerardo Mosquera, identifies these characteristics in his essay, “Plastic Arts in Cuba,” in Being América: Essays on Art, Literature, and Identity from Latin America, eds. Rachel Weiss with Alan West (Fredonia, NY: White Pine Press, 1991). See also: Linda Howe, Transgression and Conformity: Cuban Writers and Artists after the Revolution (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004); and Rachel Weiss, To and From Utopia in the New Cuban Art (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011).

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.40

1. Kristin Schwain, "Barquitos del San Juan: La Revista de los Niños, Year 13, No. 23, 2007," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.40

Schwain, Kristin. "Barquitos del San Juan: La Revista de los Niños, Year 13, No. 23, 2007." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.40