Francois de Menil is an award-winning architect and designer of the Byzantine Fresco Chapel, Houston, Texas. Olivia Hillmer (MAVCOR Graduate Affiliate, 2011) has a Masters of Arts of Religion from the Institute of Sacred Music at Yale Divinity School where she studied eastern and western medieval liturgical art and architecture. She is currently Curatorial Assistant for Exhibitions at the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University. Parts of this piece were originally presented by Francois de Menil at MAVCOR's 2011 conference Sensational Religion: Sense and Contention in Material Practice.

Francois de Menil:

After the Turkish invasion of Northern Cyprus in 1974, thieves removed fresco images from the dome and apse of a small abandoned votive chapel outside of Lysi, Cyprus. They did so by cutting the images into thirty-eight pieces. This act launched an almost thirty-year story of rescue, restoration, reassembly, transposition, relocation, and (one might even argue) transcendence.1 In 1983 those who stole the fresco fragments offered them to the Menil Foundation in Houston, Texas, claiming they were from a chapel in Turkey. The Menil Foundation, suspecting that the frescoes were looted artworks, sent letters to seven countries from which the frescoes might have originated. Cyprus returned proof that the frescoes were the same ones removed from the walls of the small Lysi chapel. Ultimately the Church of Cyprus and the Menil Foundation signed an agreement authorizing the foundation to acquire the frescoes on behalf of the Church, restore them, and build a consecrated chapel, the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, in Houston, Texas, to exhibit them.2 In exchange for this work of preservation, the Church granted the foundation a long-term loan of the frescoes.

Now, twenty-eight years later, the frescoes are scheduled to revert to Cyprus in accordance with the terms of the agreement. Regrettably the artworks cannot yet be returned to their original location; they will be displayed, instead, in the Archbishop’s museum where they will appear as art objects in a very different context.3 This not quite circular arc, at all points along its trajectory, raises many questions. These questions concern, among other things, the nature, production, and maintenance of sacred space; and the relationship between museum display, religious tourism, and liturgical arts and artifacts. Perhaps most succinctly, one might ask whether religious objects can be desecrated, restored, transported to a new location (or two new locations), and then returned to their original site, all while retaining their spiritual power. What happens to them along each step of this process? What are the poetics and politics of this story?

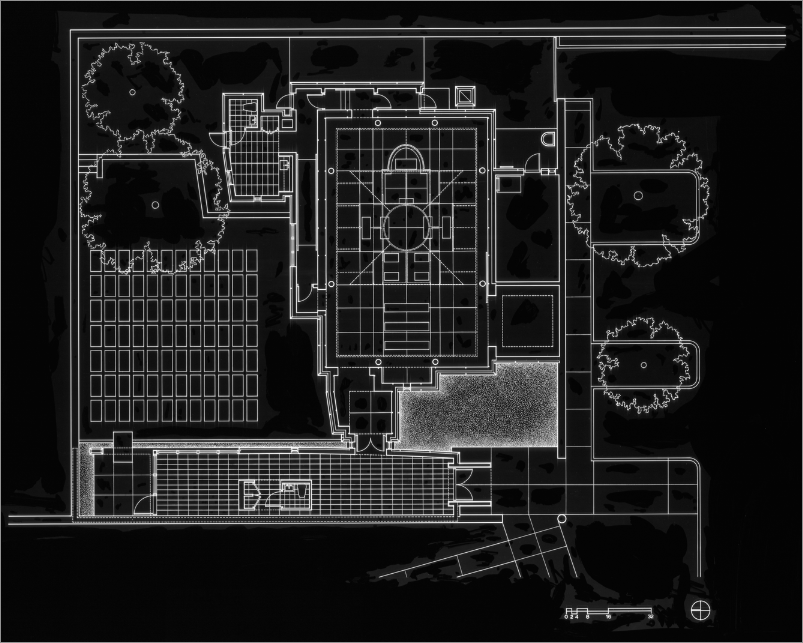

Early on we decided our chapel/museum design would be a contemporary building, but one that told the tragic story of the frescoes—a building that would be at once a lament and a celebration. We researched ancient painted churches in Cyprus, and were struck by the plans of two churches in particular. Both consisted of an older structure with a typical Byzantine shallow cruciform plan that was enclosed within a larger rectilinear protective shell. This larger protective shell appeared to have been added later. These plans seemed appropriate as models because they simultaneously anchored our project back to the time of the frescoes and seemed adaptable to the late twentieth century. From these images we developed the notion of a “free plan” organization for the project. We designed a stand-alone chapel structure that would give context to the frescoes and set this within a light-and-climate-modulated envelope. The envelope was layered into two parts: an outer skin and an inner liner or lifted box. A continuous two-foot-wide skylight space between layers would allow daylight to wash down all four walls of the building. The simplicity of the rectangular shape suggested a reliquary box, a vessel that contains sacred fragments.

Olivia Hillmer:

The frescoes from Cyprus needed contextualization to make them comprehensible, so that they would embody more than just battered pigment. This is how a reliquary functions: it protects tiny, inscrutable fragments of body, or items that have had direct contact with such sacred bodies, and gives them meaningful context. For the artworks in question here, some of this recontextualization occurred in the restoration process, but the new Houston building itself also played an important role. The reliquary that is the Byzantine Fresco Chapel contained and protected the fragile remnants of the Cypriot chapel.4 Simultaneously, it memorialized the iconoclastic action that ultimately resulted in the frescoes’ presence in Houston. The architectural reliquary at once dissolved and perpetuated the act of violence on the painted bodies.

Relics in various Christian contexts past and present have frequently been the subjects of such deep admiration that thieves have stolen them and “translated” them, moving relics from one city to another.5 Motivations for this translation have varied over time and have often differed in important regards from the Cyprus/Houston example. Nonetheless, the frescoes, like so many other relics, were the victims of exchange, changing hands and homes. The difference in materials between the “envelope” and the frescoes themselves, as well as the opposition of light and darkness, create a visual and sensory contrast that draws attention to this exchange. Although the chapel enclosed the frescoes in a new context, their very enclosure acknowledges that they are not at home.

This aspect of the frescoes’ lives as mobile relics might fruitfully be considered in relation to their return to and exhibition in Cyprus. Will the frescoes be more—or less—whole? They will be at once closer to their original home and farther from the place that gave them refuge. What will be the response of the communities of Houston and Lysi when the frescoes return to Cyprus?6

Francois de Menil:

The Houston freestanding chapel structure is based on the plans and measurements of the original chapel in Lysi—only pulled apart. As architects, we intended this breaking down of the surface into planes to evoke the way in which the frescoes were cut out of the original chapel into panels. The metal clips holding the glass panels together represent the “stitching back together” of the restoration process. The chapel structure had to create context for the frescoes, reestablishing the spatial relationship between dome and apse, and it had to have a material expression whose presence would be both surrogate for all that was missing (the floor to dome wall paintings that were present in the Lysi cathedral and were not stolen by the thieves) and yet not overpower what remained (the dome and the apse). We needed what I called at the time a “surface presence.” Etched glass presented itself as the ideal material: the immateriality of the glass intensified the absence/presence of Lysi. It created a mystical union and historical arc between past and present, between Cyprus and the United States, through an inversion of body and soul. The soul, which is typically ephemeral, became opaque in the restored frescoes, while the body of the original chapel, which is opaque, became ephemeral in the fragmented glass chapel.

Olivia Hillmer:

The intentional breaks in the glass of the “pulled apart” chapel re-imaged the excision of the frescoes, especially from an exterior view. From outside the chapel the spaces between panes of glass allowed for only fragmented views of the frescoes. The etched glass, which was translucent but not transparent, largely prevented the frescoes from being seen by visitors until they had actually entered the reconstructed chapel. Only slivers of faces or drapery could be seen from the outside, visible through the spaces between glass panels. Some of the fractures in the illumined glass of the chapel formed cross shapes. The crosses invoked theological and liturgical interpretations of acts of violence: the breaking of Christ’s body on the cross, the breaking of the bread at the Eucharist. The breaks in the glass might also remind one of the political turmoil in Cyprus, including the so-called “green line” dividing northern Turkish Cyprus from the southern Greek area.7

Visitors to the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, however, were able to cross the exterior architecture’s boundaries and breaks. Once the visitor entered the chapel space, the opaque glass no longer obscured the frescoes; instead, it illuminated them. The paintings became whole again. The visitor’s body, traveling from exterior to interior, was central in revealing the “soul” of the restored frescoes as de Menil has re-imagined it. The visitor’s bodily motion told the story of the frescoes' movement from “concealment” within the Cypriot chapel, to victim of destruction (illustrated by the re-imaging of the broken frescoes through the breaks in the glass), to refuge in Houston. The final complete view of the frescoes, surrounded by an architectural reminder of their origin, gave the chapel’s body and soul hope for reunion. Activated by the visitor, the architecture of the Chapel imagined the reunification of the frescoes and their restoration to their home country.

Francois de Menil:

The most difficult issue was the question of what constitutes spiritual space. Hanging the frescoes in empty space did not make the space spiritual. Something more was needed. We found the “something more” in the dialogue created between multiple elements: the frescoes, the glass chapel and the absence it represented, the lifted metal liner box, and the light. The starkness of the space in conjunction with the simplicity of the materials combined with the effect of the light to create the spirituality of the space. The dialog between the frescoes and the glass chapel established the historical arc from Lysi to Houston—the dislocation, relocation, and transcendence through time.

Olivia Hillmer:

But the space claimed more than purely religious import. The joint chapel-museum nature of the space brought together two aspects of the frescoes: their spiritual significance for particular audiences, past and present, and their role as works of art. The tension and fluidity of both possible views of the frescoes was clear in the unofficial nomenclature of their enclosure. The chapel was situated among the other museums and galleries housing the Menil’s collection of art, and was grouped with these other buildings on the Menil Foundation’s informational maps and webpages, perhaps suggesting a secular space to to visitors. Even the use of seating in the space was ambiguous. In this urban Texan cultural context, the row of low benches recalled both church pews and seating in modern museums. Historically, no pews existed in Byzantine chapels. They were left unoccupied by furniture so that those present could stand. The seating in the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum, then, may have followed museum conventions more closely than religious ones. Still, the suggestion of pews, enhanced by their arrangement along a central aisle, probably helped American visitors to interpret the space. The chapel-museum remains ambiguously bi-identified.

Changes made to an artwork's context affect the viewer’s sensory experience of the object. Museum spaces normalize silence, odorlessness, and minimal visual distraction as appropriate ways to experience art objects. In doing so, they differ greatly from functioning chapels. The original chapel of Lysi was likely filled with the music of chanting, the shuffling of moving bodies, and possibly the sounds of liturgical implements such as censers being filled and swung. The Houston chapel maintained silence. Incense probably filled the Lysi chapel with its scent and smoke, and more images would have filled the original space; the Houston chapel did not receive all of the interior frescoes. Although in general the Houston chapel functioned as a museum space, removing much of the sensory context for the frescoes, from 1998 to 2002 various local church leaders led the Greek Orthodox liturgy of the Paraclesis Supplicatory to the Virgin Mary on a weekly basis.8 The chapel-museum openly wrestled with entangled tasks. By maintaining a generally more sterile museum-like environment, they recognized the importance of the frescoes as aesthetic and historic objects. Implementing weekly services of the Paraclesis Supplicatory allowed them to simultaneously preserve the frescoes' spiritual function. The space regularly transformed the frescoes and itself. It acted as both chapel and museum despite disparities between the two spaces.

Francois de Menil:

In this case, the use of a modern architectural idiom displaced place-specific and time-specific understandings and allowed the visitor to enter the experience of the artwork from “any time.” To understand the work and be able to interact with it, it was crucial to have a place that was Byzantine in shape, but not necessarily specifically Byzantine. The chapel provided an envelope of space for the viewer to be in and to have not only a visual experience, but also a sensory experience—feeling the frescoes in their space. Visitors walked into a complete environment, which evoked a range of senses beyond that of just looking. It was a charged space where the glass chapel structure continually forced the viewer to arc back and forth between Houston and Lysi. I noticed a physical sense of respect in the bodies of the people who walked into the space. They reacted to the whole dynamic environment, not just the paintings.

Now that the frescoes are going back to Cyprus, I imagine them being returned to the small chapel at Lysi, and I imagine their return involving yet another inversion/reversion of body and soul.9 The return to Lysi would be the opposite of the inversion of the project in Houston. The opaque protective envelope would become a transparent glass envelope allowing the visitor to experience the chapel in its context and environment, but bringing the life supporting quality of conditioned air to the chapel. We would reestablish the bond between senses and religion playing together, by constructing a series of compression/decompression spaces that the viewer would pass through on their route to the chapel space. These spaces would be tantamount to a preparation ritual, like the washing of hands, before entering the sacred domain. There would be an intense bond between the art and the body of the senses.

Notes

Notes

1. The use of the word transcendence here relates to the idea that the frescoes, having been stolen and cut into pieces, then restored and returned to spiritual function in a consecrated chapel in Houston, Texas, thousands of miles and across two seas from Cyprus, have now been imbued with that history and therefore become something other than what they were initially. Their story has radically changed them and, even if they are reinstalled in the original chapel, they will never be the same.

2. The circumstances of the acquisition are related in Anemarie Weyl Carr, A Byzantine Masterpiece Recovered, the Thirteenth-Century Murals of Lysi, Cyprus (Menil Foundation and University of Texas Press, 1991). In brief, the frescoes were offered to the Menil Foundation by an English art dealer on behalf of the thief Aydin Dikman. The foundation, suspecting the frescoes were stolen, inquired about their provenance through the Department of Antiquities of a number of possible countries of origin. Cyprus submitted proof that the frescoes had come from Lysi. The Church of Cyprus, the Republic of Cyprus, and the Menil Foundation came to an agreement that would to allow the Menil Foundation to rescue and restore the frescoes on behalf of the Church. The thief Aydin Dikman was apprehended and sent to jail (although for other thefts, not for the theft of these specific frescoes).

3. Francois de Menil's understanding is that they will be displayed in the Archbishop’s Museum until it is possible to return them to Lysi. This unfortunately may never happen unless Cyprus were to be reunified under Greek rule. The de Menils investigated the possibility of having the frescoes returned to Lysi through UNESCO, but were told that it wasn’t possible to guarantee their safety if they were returned.

4. Indeed, the frescoes depict holy bodies—the very people whose bodies are said to be found within reliquaries in Orthodox churches. The presence of these holy bodies resonates with Francois de Menil’s vision of the American chapel as a reliquary for the Cypriot icons.

5. See Patrick Geary, Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990).

6. As of March 2012, the frescoes have been returned to the Archbishop’s museum in Nicosia. In honor of the frescoes' departure from Houston, Archbishop Demetrios, Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church in America, celebrated a special service. The people of Houston were saddened by the departure and flocked to the chapel to see the frescoes during their last days. In Cyprus there were celebrations and the return was covered on the local news. It was an occasion both joyous and political.

7. The “green line” runs along the United Nations Buffer Zone in Cyprus. This demilitarized area simultaneously provides a welcome respite from armed conflict and serves as a reminder of the division of the nation.

8. The liturgy of the Paraclesis Supplicatory articulates humanity’s sinfulness and directly requests Mary to intercede on its behalf.

9. de Menil's thoughts here are hypothetical. At this time there is no provision for further involvement on the part of the Menil Foundation or the architect, Francois de Menil. As de Menil writes, “The idea of the further or last inversion/reversion was an idea that, it seemed to me, would be appropriate. The small chapel in Lysi—not climate controlled—would need to become a safe and conditioned environment for the frescoes. So I thought that the inverse of the chapel in Houston would be appropriate gesture and design strategy.”

Imprint

10.22332/con.ess.2014.4

1. Francois de Menil and Olivia Hillmer, "Transforming Absence: Perspectives on the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum," Essay, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.ess.2014.4

de Menil, Francois and Olivia Hillmer. "Transforming Absence: Perspectives on the Byzantine Fresco Chapel Museum." Essay. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.ess.2014.4