Ashley Makar is the Outreach Coordinator for IRIS--Integrated Refugee & Immigrant Services, in New Haven, CT. She's been working to engage faith communities in refugee resettlement since completing her Masters in Divinity at Yale in 2013. She is a former MAVCOR fellow and graduate student in Religion and the Arts at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music (ISM). Makar is also a writer, with essays in The Washington Post, Tablet, and Killing the Buddha.

This conversation about spirituality happened in the home of Aparajita Guha in Rexford, New York, on June 20, 2012. Guha, a practicing Hindu, is a family friend of Ashley Makar, who is a practicing Christian. Ashley Makar's opinions as expressed in this interview are her own and do not reflect those of MAVCOR.

Aparajita Guha, a project manager for a multi-national company, grew up in her family home in Calcutta, India, where she studied philosophy. She is an avid reader and a freelance author. She writes children’s stories and poems, drawing inspiration from her life with her grandchildren. She lives in Upstate New York.

Ashley Makar: What is your spiritual background?

Aparajita Guha: My spiritual background, I would say, is the way I grew up with my father, practicing not religion per se, because we felt very secular—you know, believing in all faiths. But he always recited the whole Gita, which is seven hundred and twenty-eight couplets, I think. That’s the eighteen chapters. He knew it by heart. He did it before going to work, or after coming home from work.1

Ashley Makar: Each day?

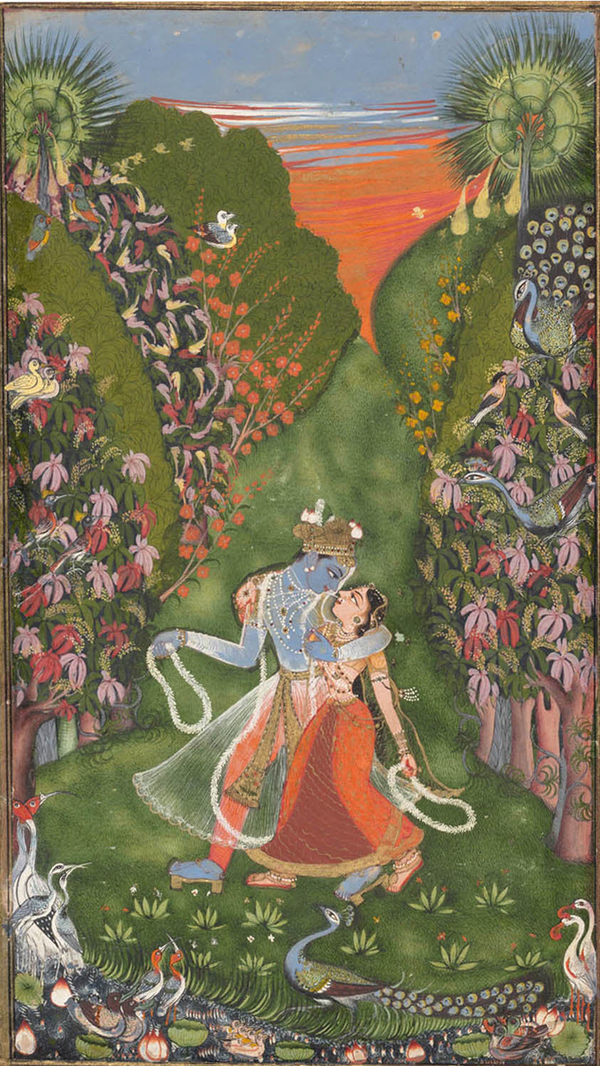

Aparajita Guha: Each day. It was amazing. It’s in Sanskrit. I remember just listening. And then he had the icon that we had and we grew up with. I find so much solace in that, because I grew up with it. It’s of Krishna.2

I later realized that they say, like even for meditation, focus on something you love. Just that one thing, whatever you pick. Somehow it became that my source of energy and the positive in everything was always from Krishna. That’s from my father’s meditating daily. He didn’t go to temples. He said, “You don’t have to go anywhere. You can just do it in your home.” So that’s part of where I think my associating my spirituality with that image of Krishna came from.

Ashley Makar: Right.

Aparajita Guha: Krishna imparted the lessons to Arjun and the Gita is those lessons. Have you read the Mahabharata?3

Ashley Makar: No, only parts.

Aparajita Guha: The Mahabharata isn't just a great epic (you know, it’s the longest and biggest), but the narrative, it’s almost like, I say, whole life’s lessons in there. About ethics, about politics, about everything. It’s 3,000 years—more than that, I think—old. It became spiritual, obviously, later.

There are many images of deities in Hinduism, but I always, because I grew up with Krishna . . . My father was very positive about everything. He would say, “If you are open to the universe, everybody has that potential. It’s there, and you just have to be ready to receive and open your heart.” I always find you cannot reason the existence of God, if you call it God, or the universe or some superior power. It’s something beyond reason.

Ashley Makar: When he was reciting the Gita, did you know the stories? Did you understand the Sanskrit?

Aparajita Guha: Yeah, I did. Later on—in high school—I took Sanskrit. In college I took Sanskrit. Sanskrit is like Latin. It’s not used as a conversational language, but Sanskrit is the root of a lot of Indian languages, just like Latin is for European languages. It was a language of the scholars, just like Latin was. So I did understand.

The Gita has eighteen chapters, and the first six are divided in three divisions: “Work”—what you do—, and then “Knowledge,” and then “Devotion.” The Devotion section is actually in the middle. I always found chapter 12 stuck with me, for some reason.

Ashley Makar: It was a Devotion chapter?

Aparajita Guha: Yes. It was. I found it very easy to remember. Just from listening I would always know it by heart, that chapter. It’s not that I agree with everything in the Gita, but I find a lot of wisdom and profound statements. And I have a lot of questions that I wish I could ask somebody—just to talk. Most of it is amazing. Some of it I say, I don’t think Krishna said those things. You know, they get changed. In any religion, you find contradiction. If they’re saying this, then how can they say that? Spirituality. How do you define spirituality?

Ashley Makar: I’ve thought about that a lot, and I have a lot of trouble with that. I think it has to do with a sense of the sacred, some sort of experience of the sacred, and maybe some sort of practice around that. But I think it’s very hard to define.

Aparajita Guha: Yes. I have the Gita and what I do everyday, yoga and meditation. I don’t read the entire Gita all in one day. I just do one new shloka, or couplet, and then I think about that. And then I have five or six, my favorite ones, and I recite them.

Ashley Makar: Those are the same each day, and the others?

Aparajita Guha: Yes. The six are the same each day, and then the others—I just start from the beginning and go to the end, in a circle. Then I do my yoga and meditation. I always find that I feel—when I see, especially the wars, and the people not agreeing—I feel, if everybody had a sense of spirituality…

We talk about being diverse—I find it to be a very static concept. Because I think, in order to be dynamic, we need a sense of spirituality, so that we can discuss our deepest differences with difference.

Ashley Makar: Right, and to acknowledge those differences.

Aparajita Guha: To acknowledge and then still to be able to sit across the table and discuss. Then, you can have peace. I don’t know why that can’t happen.

Ashley Makar: It’s disappointing. I’m interested in interfaith dialogue, but then anytime I go to a lecture or an event that’s supposed to be interfaith dialogue, it doesn’t feel substantive. I think it’s because people are afraid to talk about differences. Those who are there want to talk about what’s common. But then it’s not productive.

Aparajita Guha: Yes, exactly. That’s what you have to do. With respect, you discuss the deepest differences respectfully . . . I don’t know if you have heard of Vivekananda. He’s a Bengali monk who started a center in the nineteenth century. He was born in Calcutta. His guru was Ramakrishna. He [Ramakrishna] was also a saintly man. He died when he was fifty. But his was the devotion . . . Vivekananda went to him and just asked directly “Have you seen God?” And he said “Yes.” See, that’s the faith. And Vivekananda is the one who took Hinduism all over the world.

Ashley Makar: Oh, really?

Aparajita Guha: He died at the age of 39. He came to North America, and the first place he landed was Vancouver. There was this parliament of religions; they had a conference in 1893 in Chicago. He represented the Hindu faith.

Ashley Makar: Ok. I have heard a little about him.

Aparajita Guha: I used to carry in my purse a little book of his three-day lecture series, what he said. If anybody asks me about Hinduism, that’s what I tell them to read. It’s just amazing. He addressed everybody as brothers and sisters of America, and so they just broke into huge applause. And then he said, “God forbid. I’m not asking anyone to become a Hindu.” Because all faiths, you know, go to the same place. You call God Allah, Christ, whatever you call God. I just love his lectures and what he wrote. That’s, I think, the essence of Hinduism, more a philosophy. And it becomes ritualistic. I definitely think that helps. Some people can do it on that intellectual level and some cannot: they need an object or a picture or an image. And that’s fine. Like I said, even when I am anxious, I just close my eyes, and I visualize Krishna. And then it sort of becomes all one. But just even saying, thinking that name.

Ashley Makar: Why do you think your father was most connected to Krishna?

Aparajita Guha: I think because he lost his parents when he was very little. So he just took to Gita and Krishna. And I got that from him. My father used to have tremendous positive force in him. He would say, “Oh, that’s going to happen. You’re not going to be sick.” It had so much strength and energy, positive energy. I would see that work. I believe in that, and I believe in prayer. There’s amazing strength in prayer, I think.

Ashley Makar: I do, too. I wish that the medical community would appreciate that more. Because, even if you’re not expecting a miracle to come of prayer, it actually makes me stronger to do it.

Aparajita Guha: I do believe—miracles have no explanation, but you have to have that. I don’t find it as contradictory to the rational part of our brain, or whatever, the human being as a rational animal. I find it’s very important. Even now you see things happen you really cannot explain by reason. And that’s when it tells you, everything cannot be explained by reason. The power of prayer and your belief in something, it’s main thing is that positive energy pulling from all directions, it can only help.

Ashley Makar: Can you talk about any image—in addition to the Krishna image, any other images or objects that are significant to you? It can be in the home, or maybe at a particular temple.

Aparajita Guha: Ok, I see. But everything sort of becomes that One. I do have Kali. They’re all different forms, it’s sort of like whether you use the cross or Christ. I sort of feel that they are all—Krishna and Christ—they’re all the same. I feel that they’re just different times. I feel that, as soon as you’re born, I think you’re limited by the body. Even as close to perfection as one can be. That’s what we think of gods: as all perfect, but still they are limited, because they are born. They are born to suffer and help save humanity, but still they are also limited. That’s why, when we read about them, we see . . .

Ashley Makar: The flaws.

Aparajita Guha: Yes, the flaws. That’s part of them. But you also see how evolved they are, so you can aspire to be—like we say namaste, what it means is “I salute the divinity in you.” I always feel that everybody has that divinity. And as much as you have, you can go up or you can go down. So the baser elements are—call it whatever, demonic, devil, whatever. But I always just pray that if everybody would just go upward, toward the divinity, there wouldn’t be any problems.

Besides Krishna—there are many gods. Like Durga, Durga is the goddess that Bengalis celebrate with the biggest festival, Durga Puja. Durga is a symbol of strength. And she’s a woman. I have images of Durga. I have images of Kali. I have Hanuman, Ram. But, I grew up with Krishna.4 That is what it all comes down to. And I know that that’s because of my father. That’s what stayed with me.

Ashley Makar: And it sounds like, with Durga, you can see the significance.

Aparajita Guha: Yes, cultural community, to the Bengalis. It’s more of a festival. Yes, it’s fun, but I find more peace and tranquility and calm in meditation. You know, you want to get to that place, and that I get from . . .

Ashley Makar: From Krishna?

Aparajita Guha: Yes, I think we all need something. What’s yours?

Ashley Makar: You know, actually, although I’m not Catholic, I’ve been learning a lot about the Catholic saints. I think it’s very similar: different saints having different attributes. So, for example, recently there was a feast day for St. Anthony of Padua, who is the patron of lost things. And I was thinking about lost things—both, like, very small, something silly that I lost, but then also larger things. I was reading about what people do for his feast day. They said that one of the practices is to make bread and donate it. I don’t think anyone does this anymore, but in the past, people would make bread the weight of someone who was lost, which, obviously, I can’t do. But I actually had lost a book in Jerusalem a couple of years ago.

Aparajita Guha: Oh!

Ashley Makar: I got it at a used bookstore. You know, sometimes you buy a book in a foreign place, and it’s really special to you. I think I lost it on the street. So I was trying to make bread the weight of that book.

Aparajita Guha: St. Anthony. Is there a—I’m thinking of St. Christopher. Is there a medal?

Ashley Makar: Yes, I think there are medals for almost all the Catholic saints. So there’s not a particular image of divinity that I focus on, but I think I like to have different periods in my life where I focus on one or the other. In fact, recently—I volunteer at a yoga studio in New Haven, and one of the teachers at the studio gave me a graduation gift. She gave me a framed picture of Saraswati.

Aparajita Guha: Oh, yes, the goddess of learning.

Ashley Makar: Right, and so, I put it over my bed. I really love her—you know, she’s with the lute, and she’s on a swan.

Aparajita Guha: Right, right. The swan is her transport.

Ashley Makar: And I would love to learn about her and then find a mantra. You know, for me, I’m a Christian mostly culturally, but I believe that . . .

Aparajita Guha: All faiths . . .

Ashley Makar: So I’m actually really interested in learning more about other deities, and I sort of organically find a prayer practice to do that. So, like with St. Anthony, baking the bread, while the dough was rising I was saying certain prayers to St. Anthony. And so, if I learn more about Saraswati, I could do some devotion to her.

Aparajita Guha: Right. Because we, also, I remember, in our home, Krishna was like a daily practice, but when it was Durga Puja, we had the worship of Durga. Durga’s daughter is Saraswati. Durga has two daughters: Lakshmi, she’s the goddess of wealth and beauty, and Saraswati’s the goddess of learning. There are specific days when you do Durga Puja. She’s the autumn deity, so it’s the autumn festival. It’s not the same like the twenty-fifth of Christmas. It will be autumn, but we follow the lunar calendar, so, each year, the almanac will say which four days this year will be the Durga Puja.

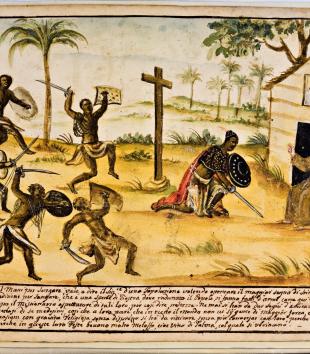

In Durga’s story there is a demon, he’s called the buffalo demon, because he could take different forms, and he was wreaking havoc. All the deities, the demi-gods, we say, the saints, they are in trouble, so all of them got together. The trinity we have is Brahma, the Creator, Vishnu, the Preserver, and Shiva, the Destroyer. For the cycle, you need all three. And so, with each one’s strength, they created Durga.

Durga has four children: Ganesh,5 whose head is the elephant head, and Kartikeya; Lakshmi and Saraswati are the daughters. Ganesh is the wisdom, he was the scribe who wrote the Mahabharata, which the sage Vyasa dictated, created. Kartikeya is the warrior. Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and Saraswati, the goddess of learning. I remember both of them were worshiped during that time. After Durga Puja, I think after one month, within a month, is Lakshmi Puja. Then after two, three months, in the winter time, is Saraswati Puja. Because she is the goddess of learning, all schools and colleges would celebrate. The school I went to was a secular school, so we didn’t do any particular worship, but all the communities would do Saraswati Puja. At our home, we did. And there are prayers you offer to Saraswati in Sanskrit.

Ashley Makar: I would love to learn some of them.

Aparajita Guha: I can email you the prayer and the English translation.

Ashley Makar: I would love that. I actually like knowing the meaning, but saying the prayer in the sacred language.

Aparajita Guha: I can transliterate it: Saraswati Mahabhage Vidye Kamalalochane| Vishwaroope Vishaalaakshi Vidyam dehi namostutey. So, what it’s saying is, Saraswati Goddess, I am imploring you to give me knowledge.6

Ashley Makar: Thank you.

Aparajita Guha: Sure, those we know by heart. Lakshmi, also, I know the prayer of Lakshmi. Thursday is supposed to be the Lakshmi day. Usually you do the prayer and you offer fruits. My husband will be doing it now, usually for Thursday.

All the stories are so much fun. In the story of Durga, she must control this buffalo demon who is wreaking havoc. Durga was given ten hands, one for each weapon, each by one of the deities, one of the gods (we call them devas, so they are more demi-gods). Finally she was able to kill the buffalo demon. But, for daily practice, I stay with Krishna.

Because Krishna is dark, he’s called the blue god. A contemporary scholar wrote a book on Krishna, the blue god: he took a couple of shlokas and gave the divine explanation of them—Krishna was born a man, with his flaws. Here is the divine and the human.

Ashley Makar: What’s the book called?

Aparajita Guha: The Blue God.7 One of my friends called and said, “The human part with flaws, that’s almost pornography.” I said “What?!” Because he’s known to be a lover of all women, all these gopis, we call them, the milkmaids. They loved him. Everybody loved him. He would play the flute, and then everybody would fall in love with him.

Ashley Makar: He was human.

Aparajita Guha: That’s right, human traits. Divine and human. I did not find it the way my friend saw it. Yes, there were parts when the author, Ramash Menon, was talking about the gopis, the milkmaids, the stories that we read, but it was very literary. But my friend said, “I didn’t think that.” The divine and the human, I thought, that’s a very unique way that Krishna addressed life. So full of wisdom. Not everything, I agree. When I find something that strikes a discordant note, I think, Krishna didn’t say that. I’m sure that was something else. You know, you say something to someone, they say it to someone else, how it changes.

Ashley Makar: What role does physical space play in your practice? Like in the room where you do puja. Or anything in nature. Or in the temple.

Aparajita Guha: I remember the sages and the saints, they would find their favorite spots, like Buddha under his tree, under the bodhisattva tree.8 For me, I used to carry a little book, but now I know the prayers that I do. If I’m home, then I have a room, but I’m not confined to that room. I can do it any place.

I used to carry a picture of Krishna, but I misplaced it. In my bag, actually, I have—I try to be very adaptable—somebody gave me a picture of Kali. I know that Krishna, Kali, it is how you are calling and how you are seeing. It’s all the same. I know the divinity, really it has no form. I believe in that.

I have that Kali image, that picture, in my purse. It’s not Krishna’s picture that I have, but to me it’s the same. Because finally, it has no form. It blends into that—whether it’s om, or . . .

Ashley Makar: But we need the form, to access it.

Aparajita Guha: I cannot speak for everybody, but form helps me to get to the formless. Yes, that’s why, even though I get my strength and all through Krishna, I have Kali. I’m not going to go crazy that I don’t have Krishna’s picture. I know that actually they are all blending into the formless divine. Everybody calls it differently, whether you call it God, whatever you want to, or Raman.

Ashley Makar: Have there been any teachings in spiritual communities that you’ve been in about images or objects? Or sensory experiences that have been significant to you?

Aparajita Guha: Sometimes when I go to temples, there are certain songs, devotional songs. Some songs would give me a feeling, I wouldn’t say a feeling of ecstasy, but it is a feeling of something. Not in the same place or from the same song always. But sometimes there is a sensation. It’s something very different. Different in the sense, it’s a joy. I don’t know if it’s euphoria. It’s a joy, that’s what you feel.

That reminds me, one of my favorite, favorite pieces is Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” When I listen to that it totally takes me somewhere. I mean it’s just, I cannot describe it. It just takes me somewhere. There is one, Krishna’s one song, there is this singer, who has an amazing voice. He’s eighty now, his chanting, that would take me. So they are two completely different sources, but that tells you: ultimately, they go beyond any geography or culture. Spirituality or the divine that you are seeking, you can tap into that anywhere. It doesn’t have to be any specific something.

Ashley Makar: It can be through sound, through image.

Aparajita Guha: Through sound, through image. Also, in different languages. One is from India. I get the same feeling, it’s like something divine, I feel. Of course, it’s connecting with you in certain ways, but also, if you see or hear an almost-close-to-perfect something—music, an image, a painting. I always find that one chant and “Ode to Joy” do that.

Ashley Makar: Yes, actually, I took a class on theology and aesthetics. We looked a lot at Plato. He said something about the idea that the soul knows the music of the heavens, or the music of the spheres, and then comes to earth and isn’t aware of it. But when they hear it again, they recognize it.

Aparajita Guha: I’m getting goose bumps.

Ashley Makar: Yes. They recognize it. One of my teachers, who is a Catholic theologian, he says this kind of recognition is like a way of being reminded of God. It’s interesting how sound seems to have a special way of doing that.

Aparajita Guha: Yes. More than visual. Auditory, and more music, I think. Actually, another chant that I thought of is the Gregorian chant. Again, just thinking of it, I’m getting goose bumps. It just absolutely does something. And the same way, there is a chant in Sanskrit that . . . It’s just something else, incredible.

Ashley Makar: Does movement play a role in your spiritual practice?

Aparajita Guha: Like swaying or dancing or something like that?

Ashley Makar: Or yoga.

Aparajita Guha: I find yoga is grounding you, helping you get focused, because your mind, it goes everywhere, then my way of getting back, to be on focus, is again via Krishna. Then there is nothing. That’s the goal. First Krishna, then from there you go to the formless, which is hard to do. Still, I have to try everyday in the morning. There will be days when it is very short, not half an hour, but I still have to—even if I skip the yoga part, I have to still do the prayer part.

Ashley Makar: And since it’s in your heart, you can do it anywhere.

Aparajita Guha: Yeah, anywhere. Right. But that, definitely yoga—I didn’t think of that as movement, but that definitely helps. Very relaxing, actually.

Ashley Makar: I find myself, if I get anxious about something, if I just do even one posture, like a forward fold or something, it helps a lot.

Aparajita Guha: Right, gesture. Yes, I have a regimen. I started yoga, which my father did, when I was seven or eight. Then I went to a yoga school in India, and I did it for many years. When I came here I was twenty, and then I didn’t do it for a long time. Then I said, you know, this is something I know, and it really helps. So I took it up again in Cleveland. Since then I have been doing yoga. I was in a class here, and I loved the teacher. She moved to California, and then I said, you know, I’ll just do it at home. Whatever I learned, I can do everyday on my own. That definitely helps. Besides really helping with your physical limitations, like arthritis and whatever I have . . . That’s definitely a movement, like you said, yoga, because I do that every day.

Ashley Makar: And you do that before your meditation?

Aparajita Guha: My routine is, I do the Gita—one new couplet and then my six regular. And then I do the meditation and then the yoga. Yoga is the last, and I end with shavasana, the corpse pose. I love that. When I was little and doing yoga I couldn’t wait for shavasana to come and to relax. But that teacher in Cleveland was so good. She would speak about the philosophy of yoga. She used to say—many would start snoring, because you’re so relaxed. She said, you have to be awake, but not thinking of anything. They say, relax your forehead and when your mind is going somewhere else, just focus on the breathing. You’re up and awake, but relaxed.

Ashley Makar: Is there anything you would want to add to this conversation about images and objects or sensory experience in your spiritual practice?

Aparajita Guha: I know what I practice, and it works for me. Everybody has to choose his or her spiritual practices. I just feel blessed that I am getting what I’m getting from my practice. And I think the images, they definitely, for everybody, whatever image they pick, that’s helping you get to the next level. Yes, I just feel lucky that it’s helping me practice. Krishna, get to the formless. And when I feel the joy from the sounds, those experiences are just incredible.

Ashley Makar: Also with Krishna, it helps you feel connected to your father, too.

Aparajita Guha: It does. That’s his gift to me. My parents passed away pretty early. My father was 63 and I’m 62 now. My mother, I always say that she’s the intellectual half of my parents. He was, too, but he was more spiritual. I grew up with my aunt. She was a widow, and she stayed with us, and she was like a second mother. She just passed away, just before my husband’s surgery. And I still feel she’s there. She was an amazing woman: Gave all her life, just loved us like children.

Ashley Makar: A lot of my spiritual practices often are somehow related to people I love who have died, like my aunt and uncle from Egypt. I know that the Virgin Mary was very important for my aunt and I have her little Arabic Bible. Even if I don’t initially feel connected to Mary, if I pray with an image of Mary, then I feel like I’m connected to my aunt.

Aparajita Guha: There is something, like you said, the soul, when you hear something, and you feel that connection, that’s the recognizing. You’re not always aware, but you hear something or you see something, and then suddenly . . . I think the soul is old. And it’s evolving.

Ashley Makar: A friend and I talk a lot about the appreciation of beauty, like in nature or music or art. We often joke about—she definitely thinks of herself as very secular, and I identify as religious, but I actually have more spiritually in common with her than I would with a lot of more traditional Christians. It’s funny, because she and I will be seeing something, or hearing something, and I know that we’re feeling the same thing, except that I attribute it to God and she doesn’t. That’s the only difference. It’s a big difference, but it’s also so much closer in terms of values and ethics and aesthetic experience than, honestly, what I feel when I go to most churches.

I have a question about Hinduism. So, I know in Islam and Judaism, there’s an idea of sacred sound: If you’re a Muslim, say, in Bangladesh, and you don’t know Arabic. You can’t understand Arabic, but you do the prayers in Arabic, because there’s something sacred about the utterance of the sacred language. Christianity doesn’t have that. They want the Bible to be translated in all different languages. Is there something similar in Hinduism, in that there’s something sacred just about making the sounds, the Sanskrit sounds?

Aparajita Guha: The om, I know that sound is supposed to be the origin of all sounds. The om, that’s why when they chant, and I think a-ou-m—I think those three, how the om forms. I don’t know the history or why. I just know that’s supposed to be the origin of all sounds, and that’s sacred. Sanskrit is the original language, but, you can do it in Hindi, Bengali—there are Bengali translations of the Gita, Hindi translations, so there are all language translations, like the Bible. Even though Sankrit is what is used in temples (the priest would always, when you are offering prayers, it’s always in Sanskrit). It’s definitely considered the sacred language.

I do the original Gita. It doesn’t have to be. There is a Bengali translation, but because I grew up with it, I do it in Sanskrit. And the prayers, like I said, the Saraswati prayers, are in Sanskrit, but it’s not that it has to be in Sanskrit. Like in churches, it’s not done in Latin, but in some at Christmastime, they do Latin masses. It has such a beautiful sound. Why does it do that? It does something, Sanskrit and Latin, that you don’t . . .

Ashley Makar: Have with your native language.

Aparajita Guha: Yes, and whether it’s just the way we think . . . is it by some outside conditioning, or . . . ?

Ashley Makar: I think it could be that, if it’s in our native language, then we’re more in our mind thinking the meaning. Whereas if it’s in a language that you don’t know, or it’s not your spoken language . . . You hear the sound and the sound is poetry.

Aparajita Guha: The sound to your higher something, to give you that joy.

Ashley Makar: And maybe taking the mind out of it.

Aparajita Guha: Yes, that sounds like a good explanation. But it does, when you hear it in Latin, it does something. And that could be because you’re not distracted by the meaning; you’re focusing only the sound, and you’re connecting. Good.

Ashley Makar: Well, thank you so much.

© Ashley Makar

Notes

Notes

1. The Gita refers to the Bhagavad Gita (Sanskrit: “Song of the Lord”), a renowned Hindu scripture, probably written in the second century BCE. See Jeaneane D. Fowler, Hinduism: Beliefs and Practices (Sussex Academic Press. Brighton, UK: 1997), 14.

2. Krishna is an avatar (incarnation) of the Hindu god Vishnu. Krishna is represented variously as a god-child, divine hero, prince and counselor, lover of women, trickster, and supreme being. Fowler, Hinduism, 32.

3. The Mahabharata is a Hindu epic that dates back to the ninth century BCE. It tells the story of a power struggle between two royal families. The Baghavad Gita is the sixth part of the Mahabharata, but the Gita is often used separately. In the Gita, the power struggle reaches a climax in a battlefield scene. The warrior prince Arjun tells his chariot driver to halt the chariot when he recognizes his family, friends, and teachers on the battlefield. The chariot driver is revealed to be Krishna, who teaches Arjun about divinity, good, and evil. Fowler, Hinduism, 15.

4. Puja (worship), is the core ritual of Hinduism, which can be performed in a temple or in the home. In Hindu temples, puja tends to be an event of tremendous sensual impact. Sacred texts are chanted, bells rung, incense burned. Participants smell sandalwood, jasmine, and roses as they behold devotional images covered with bright silks, gold, and silver. In the home, puja is more restrained. The person doing puja sets an offering of food and water before the image of a deity and may burn incense. The image may be adorned with jewelry and flowers. “Puja, at its heart, is the worshipers’ reception and entertainment of a distinguished and adored guest. It is a ritual to honor powerful gods and goddesses, and often to express personal affection for them as well; it can also create a unity between deity and worshiper that dissolves the difference between them.” C. J. Fuller, The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 67.

Kali is a Hindu goddess who embodies a duality of cosmic energy. She is an all-compassionate Mother, as well as a force of destruction and death. See Lynne Foulston and Stuart Abbot, Hindu Goddesses: Beliefs and Practices (Sussex Academic Press: Portland, 2009).

Hanuman, depicted with the physical features of a monkey, is a major deity in North India, where he is renowned as a monkey-god who propitiates against evil. See Sumanta Sanyal, “Hanuman,” in Encyclopedia Mythica from Encyclopedia Mythica Online.

5. Ganesh is the Bengali pronunciation of the god whose name is pronounced Ganesha in other Indian languages.

6. Guha sent Makar the translation by email, as follows:

O, the great Goddess Saraswati, who has eyes like lotus and who represent knowledge.

O, Goddess with large eyes, who takes the form of whole universe, I pray to you, bless

Me with knowledge that rids of ignorance.

7. Ramash Menon, Blue God: A Life of Krishna (Lincoln, NE: Writers Club Press, 2000).

8. Guha is referring here to the tree, also known as the Bodhi tree (the “tree of awakening”), described in accounts of the life of the Buddha. The Buddha resolved to sit under the Bodhi tree and meditate until he attained complete awakening. See Rupert Gethin, The Foundations of Buddhism (Oxford University Press, 1998).

Imprint

10.22332/con.int.2014.3

1. "Aparajita Guha: Conversation about Contemporary Hindu Spiritual Practice," by Ashley Makar, Interview, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.int.2014.3

"Aparajita Guha: Conversation about Contemporary Hindu Spiritual Practice." By Ashley Makar. Interview. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.int.2014.3