These glass eyes, set in a gilt silver frame, with black and red paint on the back of the glass, are arresting. They seem to look back intently at the viewer, seizing the viewer’s attention. This is precisely what they are intended to do by the Shvetambar Murtipujak Jains of western India who purchase glass, crystal, or enamel eyes, and install them on the faces of their three-dimensional temple icons. It is also precisely why the Digambar Jains of western India strenuously object to them, and do not install eyes on icons.1

Scholars of the Jains who focus on texts and doctrines understand that the two main sectarian traditions of the Jains, the Shvetambar and the Digambar, have been divided for at least a millennium-and-a-half over several fundamental doctrines. Should the true Jain monk be naked (dig-ambar, literally “sky-clad”), or is he permitted to wear simple white clothes (shvet-ambar, “white-clad”)? Can women become true monks? Is a soul capable of attaining liberation in the body of a woman? Does the enlightened but not yet liberated Jina (the enlightened and liberated teachers of the Jain dharma, who are worshipped and venerated by Jains in iconic form in temples and home shrines) still engage in normal bodily functions of speech, consumption, and evacuation? Are the Shvetambar scriptures authentic? They also disagree on details of the biographies of the twenty-four Jinas of this era.

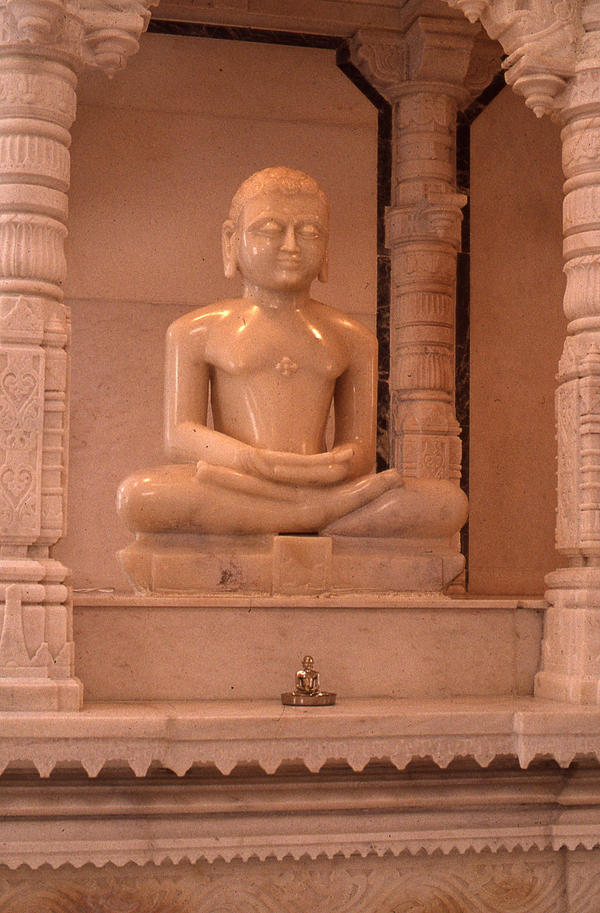

These are not, however, the differences that a visitor to a Jain temple in India (or to the several dozen Jain temples now in North America, Europe, East Africa and Japan) will first notice. Instead, someone who visits both a Shvetambar and a Digambar temple will quickly observe that the stone or metal icons in a Shvetambar temple have prominent, oftentimes outsized, eyes affixed to them, whereas the icons in a Digambar temple do not. (Another readily observable difference is that many Shvetambar icons are often elaborately ornamented, whereas Digambar icons are intentionally unadorned.2) Since most people in the icon-worshipping Jain sects (there are also non-icon-worshipping sects among both the Shvetambars and the Digambars) go to a temple on a regular and even daily basis, this distinction in icons is a cardinal difference between the sects.3

According to both Shvetambar and Digambar theology, the liberated Jina resides at the top of the universe in perfect knowledge, perception, bliss, and potential. The Jina cannot be present in any real sense in a temple icon here on earth. Furthermore, the very nature of the Jina’s perfection means that the Jina lacks any desire to act in the world, even to act compassionately, and so does not in any way respond to worship. According to orthodox theologies of the icon, therefore, the worshipper does not worship the Jina in or through the icon. Instead, the worshipper engages in a form of reflexive meditation. By gazing on the icon as a three-dimensional symbol of spiritual perfection, the worshipper reflects upon his or her own imperfections. The worshipper strives to reduce and eliminate those imperfections, and to allow the innate perfections of his or her own soul—perfections occluded by the physical karma that due to past bad actions has stuck to the soul—to gradually come to the fore.

If Shvetambars and Digambars agree that, according to orthodox understanding, the Jina cannot be present in the icon, and so agree that the icon is only a symbol of spiritual perfection, why have they disagreed about attaching external eyes to temple icons for so many centuries, perhaps a millennium? Shvetambars say that the eyes allow the worshipper, through an act of meditative projection, to imagine that she or he is actually in the presence of the living Jina. The eyes provide a powerful “as if” experience, and thereby enhance the worshipper’s efforts to achieve a state of perfection similar to that of the Jina.

Digambars disagree. They argue that by attaching the eyes, and thereby imagining the Jina to be present, the worshipper mistakenly focuses on the external, material world. This is precisely what binds the soul and keeps it in a state of ignorance and suffering.Instead, say the Digambars, by gazing upon an icon of the Jina that lacks external eyes, the worshipper is encouraged to gaze inward and reflect upon the potential for perfection of his or her own soul.

Many people in North America or Europe will only see a Jina icon in a museum. It is rare for a Shvetambar Jina icon to come on the art market with eyes still attached. If it did, it is likely that the museum would remove the eyes as part of the accession process. Conservators would object to the resin used to affix the eyes. Curators might also object to the eyes, as a form of unnecessary ornamentation that detracts from the “original” stone or metal icon. The difference between a Shvetambar and Digambar icon, therefore, is minimized in a museum setting. Only by visiting a Jain temple, or viewing photographs of Jina icons in their temple settings, will the non-Jain viewer be able to see this crucial difference between the Shvetambar and Digambar temple cultures.

Notes

Notes

1. This short essay is based on a longer forthcoming essay: John E. Cort, “God's Eyes: The Manufacture, Installation and Experience of External Eyes on Jain Icons,” in Sacred Matters: Material Religion in South Asian Traditions, eds. Corinne Dempsey and Tracy Pintchman (Albany: SUNY Press, forthcoming).

2. On the Jain ornamentation of temple icons more generally, see John E. Cort, "Dios como rey o asceta," in La Escultura en los Templos Indios: El Arte de la Devoción, ed. John Guy (Barcelona: Fundación "la Caixa," 2007), 171-79.

3. For overviews of Jain temples, icons and worship, see Lawrence A. Babb, Absent Lord: Ascetics and Kings in a Jain Ritual Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996); John E. Cort, "Installing Absence? The Consecration of a Jain Image," in Presence: The Inherence of the Prototype within Images and Other Objects, eds. Rupert Shepherd and Robert Maniura (London: Ashgate, 2006), 71-86; John E. Cort, "World Renouncing Monks and World Celebrating Temples and Icons: The Ritual Culture of Temples and Icons in Jainism," in Archaeology and Text: The Temple in South Asia, ed. Himanshu Prabha Ray (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010), 268-95; John E. Cort, Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.23

1. John E. Cort, "External Eyes on Jain Temple Icons," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.23

Cort, John E. "External Eyes on Jain Temple Icons." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.23