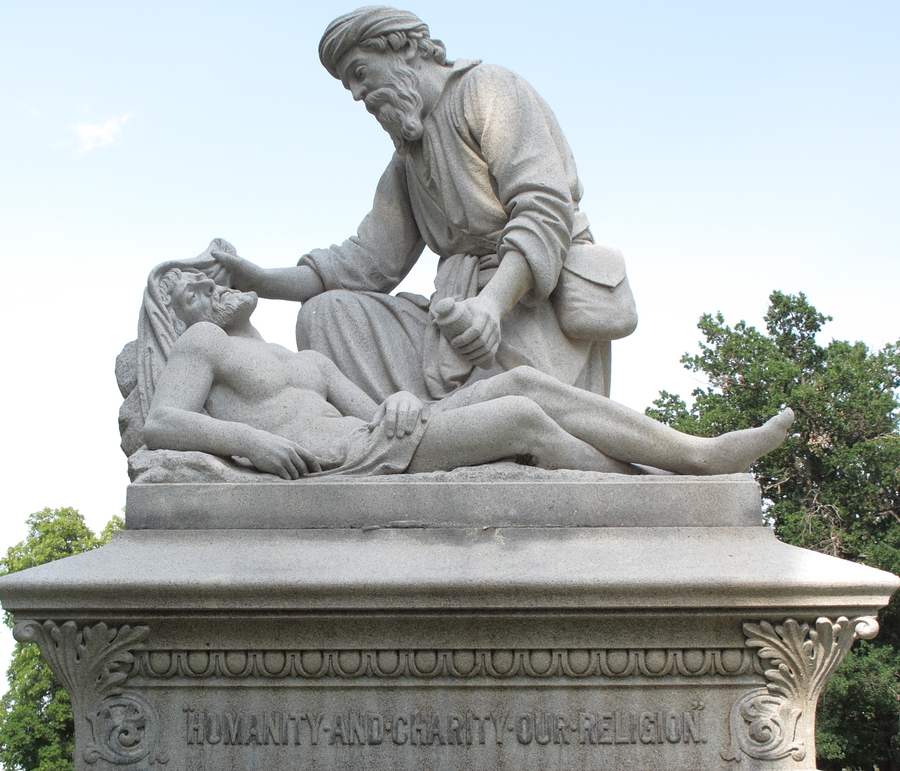

In the summer of 1900, Denver acquired an unusual sculpture to mark the last resting place of pioneer attorney Vincent Daniel Markham (1826-1895) and his wife Mary (ca. 1834-1893). Markham had chosen the plot and buried his wife two years before his own unexpected death from bronchitis following an operation for tongue cancer. According to instructions in the will he wrote shortly before his death, his executors chose a monument to illustrate the inscription “Humanity and Charity Our Religion.”1 Markham specified a cost of $5,000-7,000 to be “taken from my estate in priority of any other bequest or legacy,” from which we may judge the importance he placed on a permanent, public image of his and his wife’s religious creed. He left the form of the monument up to his executors, a probate judge, and an insurance executive, who held a competition and chose from over 30 proposals the entry of William Greenlee’s Denver Marble and Granite Company. Greenlee had submitted the subject of the Good Samaritan aiding the Israelite, a design he obtained from the New England Granite Company of Hartford, Connecticut. It was carved in the east, shipped by rail to Denver, and assembled by Greenlee’s firm. Markham’s friends apparently felt that this over-life-size figure group would best convey the Markhams’ faith.

Some clues to the monument’s meaning as a memorial may be found in tributes to Vincent Markham at the time of his death. His former law partner C.S. Thomas wrote: “His religion was the religion of humanity. He believed that the world was made for man, whose duty it is to improve and enjoy the resources of nature…”2 Markham was an avid gardener who had designed flowerbeds and plants for the monument and gave the cemetery $1,000 in endowment to maintain them. Thomas continued: “He believed that the man or woman who more nearly observes the precepts of the golden rule are more nearly perfect than others.” Following that rule himself, Markham “dispensed, in a quiet way, a great deal of money. He was always ready to divide his last dollar with any friend in need or any stranger he thought worthy.” Nevertheless, the Markhams’ charity focused on children and animals. Childless themselves, the couple contributed to orphanages and were described as “the father and mother of the neighborhood” where they lived. Mary Markham was godmother to many and was “prominent in all charitable work,” according to her obituary.3 A founder of the Colorado Humane Society, Vincent Markham allowed his pet deer, birds, and dogs to roam about their large house.

The Good Samaritan theme addresses neither children nor animals directly, yet speaks to the epitaph, “Humanity and Charity Our Religion,” in a personal way. According to the Christian scriptural book of Luke (10:25-37), Jesus told the story as a way of illustrating to an expert in Jewish law the meaning of the golden rule, “love thy neighbor as thyself.” In the story, a priest and a Levite passed by without helping an Israelite who had been attacked by robbers and left naked by the road. A Samaritan—a member of a rival ethnic and religious group—cared for the Israelite’s wounds and took him to an inn, paying all expenses. The story, as told by a Jewish Jesus, praised the Samaritan’s charity toward a stranger as superior to the lack of compassion shown by members of his own religious tradition who were too self-involved to stop and give aid.

Markham, born on his family’s Virginia plantation, as an adult practiced law from the family home until he was 32. During that time, his father owned a steadily increasing number of slaves, mostly children, and Markham may have become sensitized to their condition.4 In 1858 his mother died and he moved to the Kansas Territory where he was soon elected to the legislature that brought Kansas into the Union as a free state. At one time reported to support slavery, his will left bequests to his wife’s “colored” friends and their monument reminds all viewers that our neighbor is anyone in need. Renowned in Colorado for his legal scholarship as well as his charity, it was the latter that this lawyer sought to perpetuate.

The epitaph also suggests that established religion was decidedly not the Markhams’ religion. Judge P. J. Reed described Markham’s faith in this way: “Though not, in the popular acceptation of the term, a Christian, yet quietly and unostentatiously practicing the cardinal principles of Christianity as taught by our Savior—charity to all, and love for all created things endowed with life.”5 The Good Samaritan story demonstrated humanity and charity, the sentiment the Markhams most wished to contribute to the world they left behind.

Notes

Notes

1. Probate record 3948, Denver County Court. His age on the monument should be 69; the family Bible recorded his birth on 15 Febuary 1826, Library of Virginia, Richmond.

2. “Nestor of the Bar,” Rocky Mountain News (June 1, 1895), 1, 5.

3. “Death of Mrs. Markham,” Rocky Mountain News (September 19, 1893), 3.

4. Federal Census records of 1840 and 1850; Henry Dudley Teetor, “Hon. Vincent D. Markham,” Magazine of Western History 9, no. 5 (March 1889): 610-12.

5. “In Memoriam: Vincent D. Markham,” in T.M. Robinson, Reports of the Decisions of the Court of Appeals of the State of Colorado, vol. 6, (NY & Albany: Banks & Brothers, 1896), xxi-xxvii.

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.31

1. Annette Stott, "The Vincent and Mary Markham Monument," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.31

Stott, Annette. "The Vincent and Mary Markham Monument." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.31