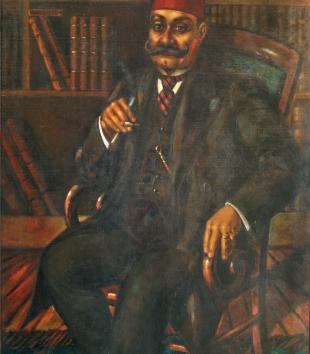

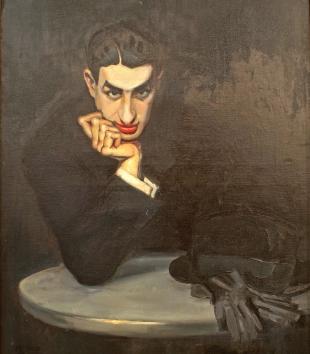

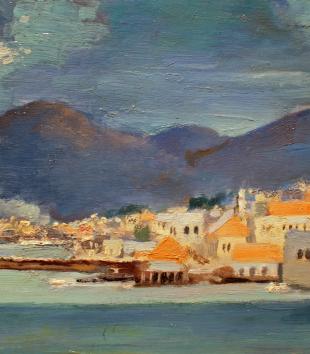

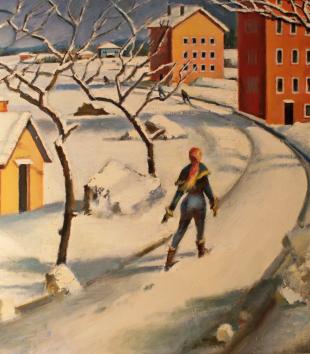

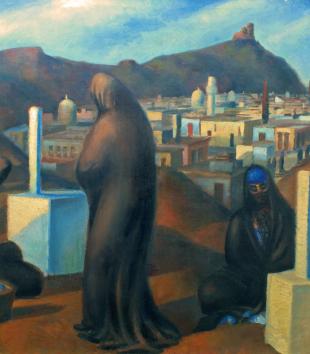

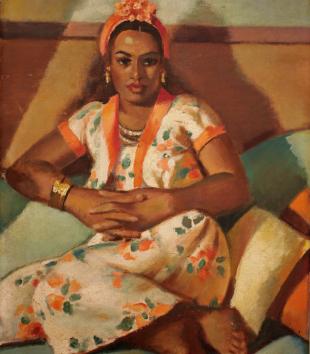

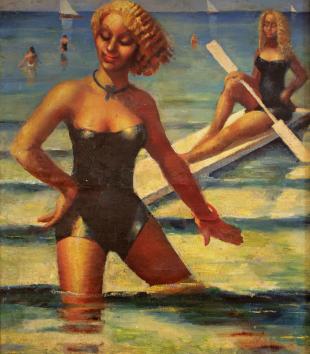

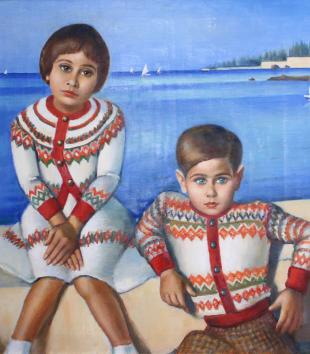

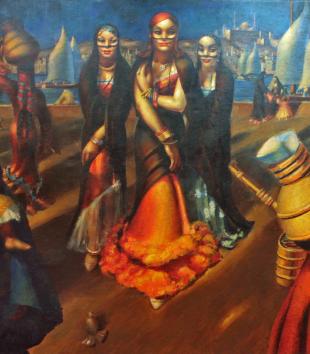

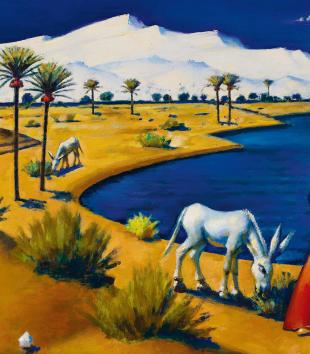

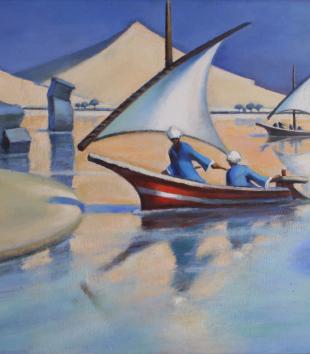

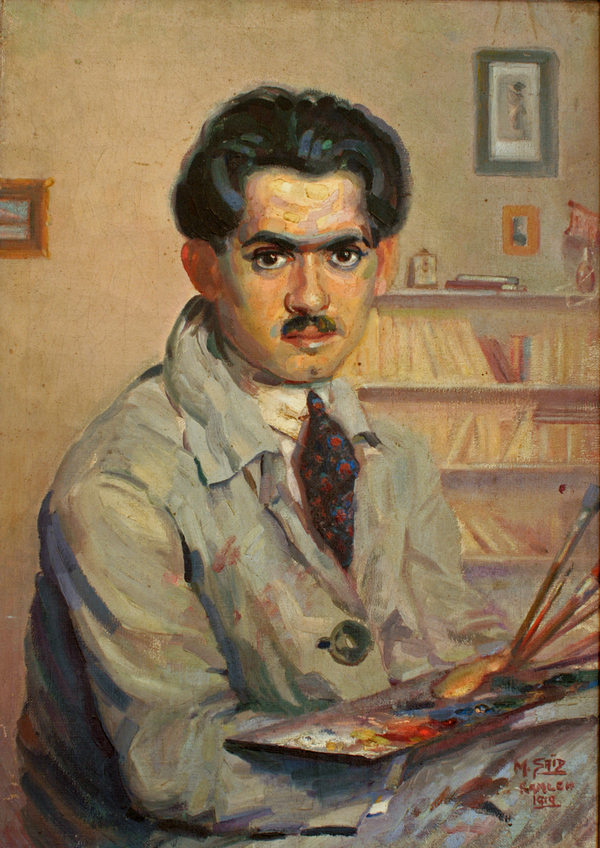

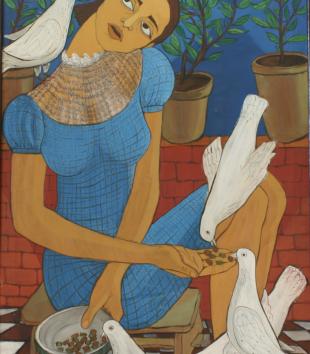

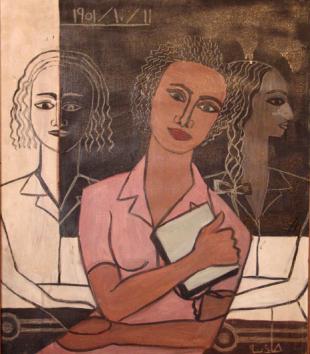

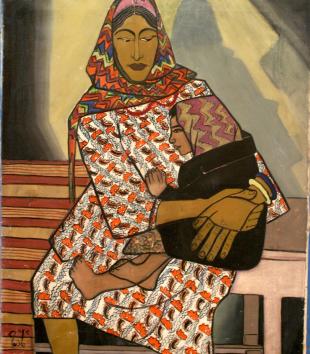

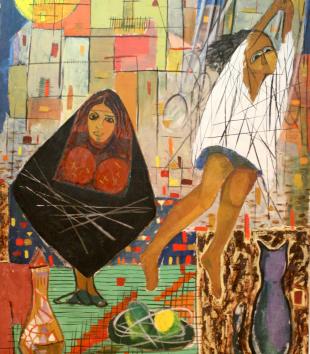

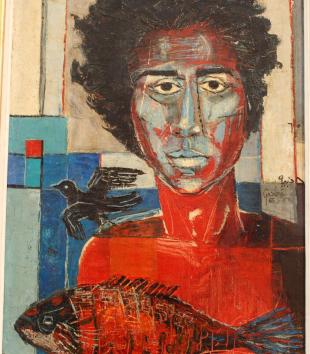

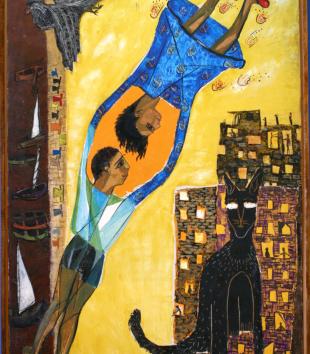

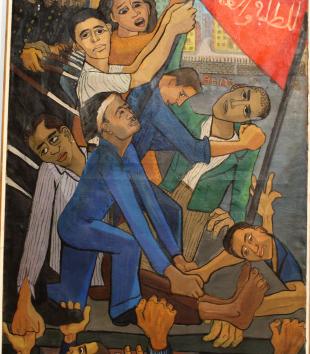

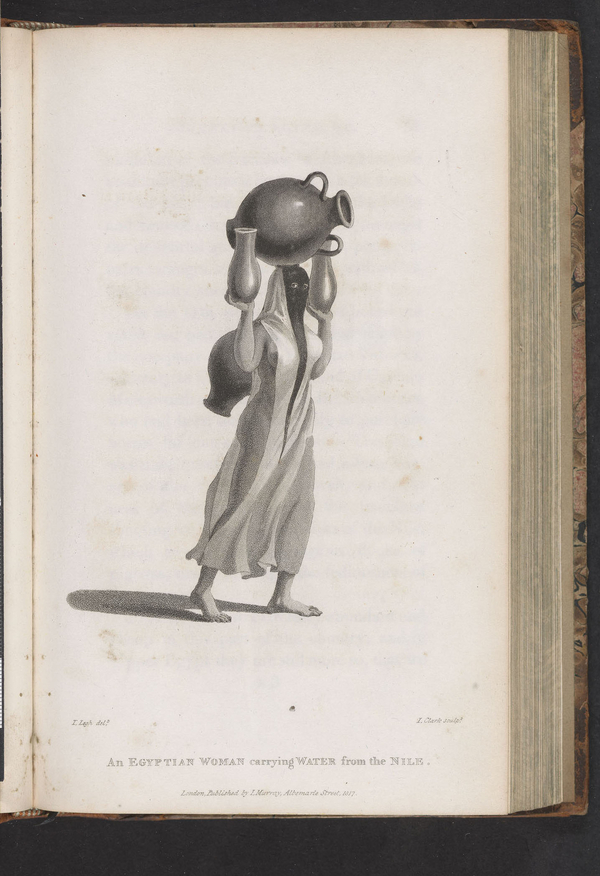

My book, Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt between the Islamic and the Contemporary analyzes the modernist art movement that arose in Cairo and Alexandria from the late-nineteenth century through the 1960s. By incorporating the previously undervalued artists of this understudied region into the modernist canon, I challenge the prevailing understanding that modern art is largely a Euro-American phenomenon. As such, this book serves as post-colonial critique, providing new ways of understanding Egypt’s visual culture, as well as modernism, as a global phenomenon. In what follows, I introduce my reader to the problematic intellectual paradigms of modernism in art history and detail the new approach that I develop in my book for modern Egyptian art. I then analyze a selection of artworks, which are not included in the book, and present how they relate to the overarching themes detailed below.

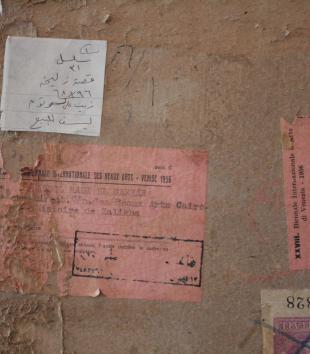

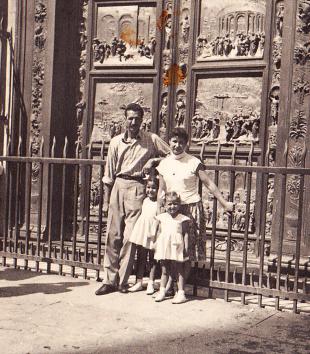

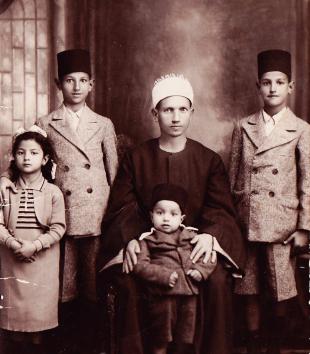

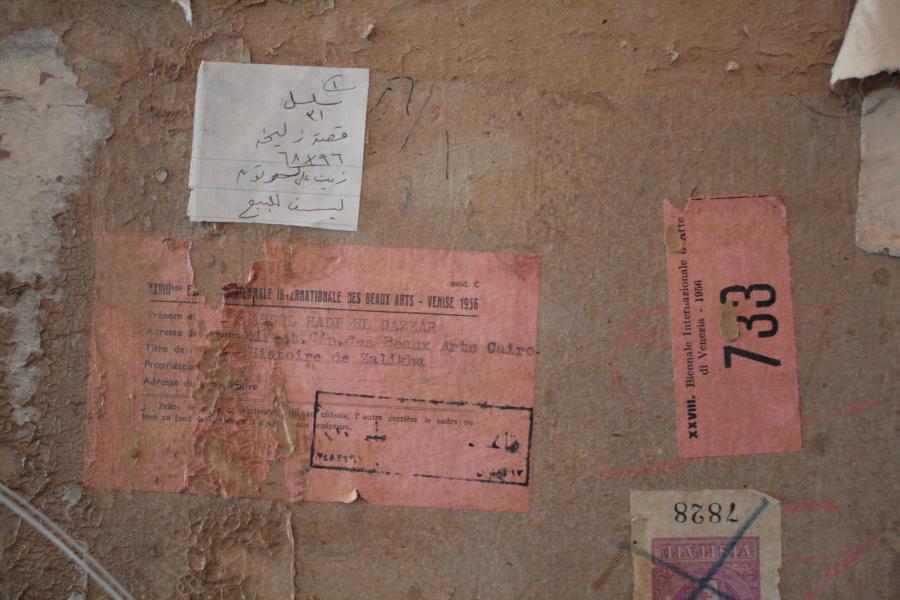

The paucity of knowledge about modern art produced outside of Western Europe and America prompted me to take a deep dive into the art history of modern Egypt. Over the last ten years, I have located and evaluated primary sources such as state correspondence, art criticism, and physical artworks, approaching them as part of the global phenomenon of modernism. Admittedly, studying this corpus of visual art has often proved challenging, as Egypt does not have thorough artist archives. The families of the artists analyzed in the book provided essential information and resources.

Why focus on the Egypt’s modernist art movement? Egypt played a central role in twentieth-century networks of politics, trade, and culture. However, Anglophone scholarship has largely overlooked Egypt’s agency in the creation of modernity. As such, Egypt’s modernist art movement provides a powerful argument for the importance of Muslim networks to global modernism. To be clear, however, I am not suggesting that Egypt is more important to the creation of modernity than any other nation that Eurocentric understandings of global history have similarly ignored. Rather, my book argues that if we take diverse modernist histories more seriously, we will have a richer understanding of the visual cultures of the world we inhabit.

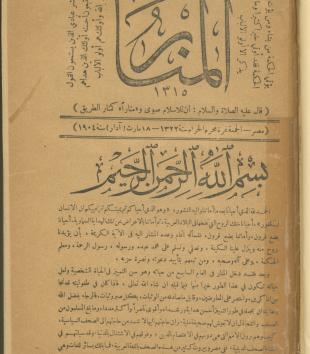

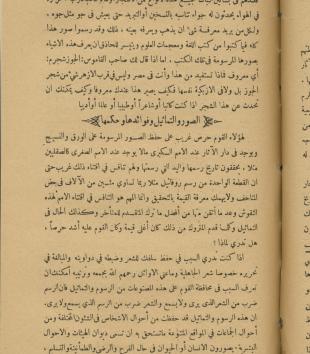

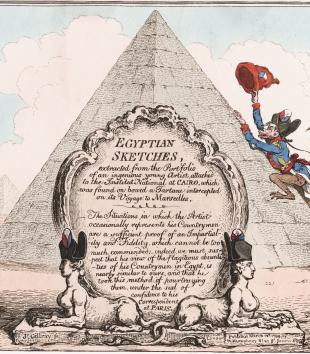

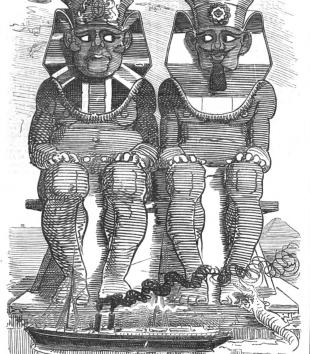

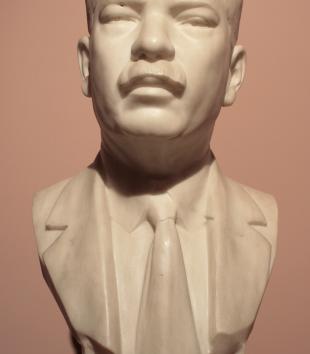

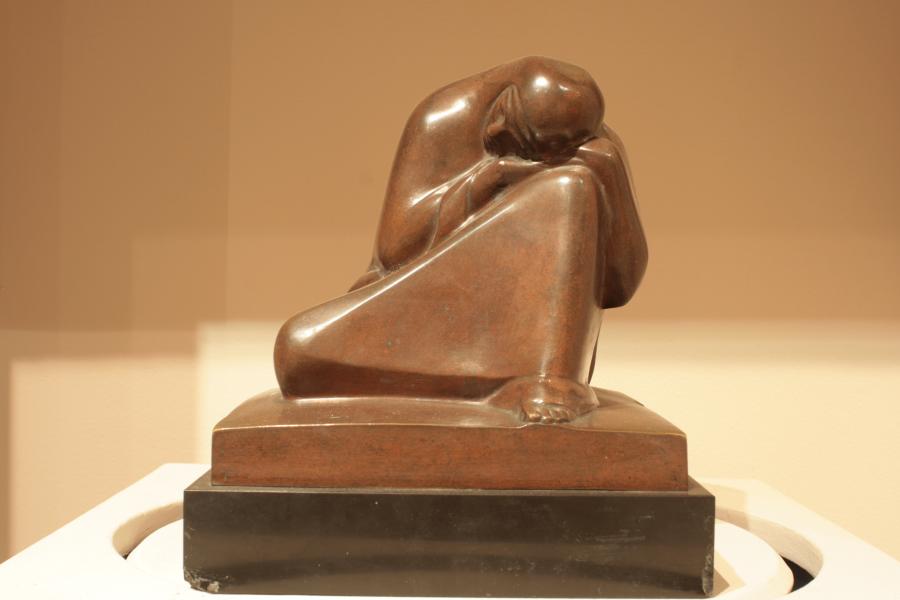

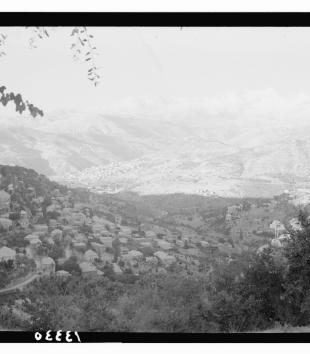

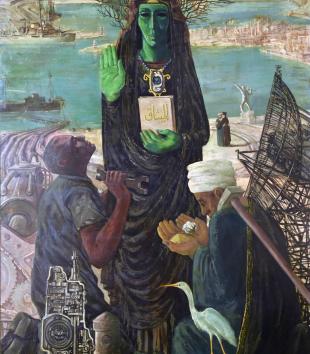

Several factors came together to make Egypt a particularly vibrant site for the rise of modernism. Due in large part to the Suez Canal, which opened in 1869, Egypt’s twentieth-century economy was robust. This robust economy fostered the institutions and markets that cultivated communities of professional artists in Cairo and Alexandria. Cairo was also a capital of the Nahda, the renaissance movement of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries that positioned art institutions as crucial to society’s progress. Moreover, Egypt’s world-famous ancient art and monuments, from the Pyramids of Giza to the magnificent 1922 discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun, gave Egypt’s artists a level of recognition abroad that artists from other non-European regions may not have had. As I demonstrate in Chapter 2 of the book in relation to the artist Mahmoud Mukhtar, this association with ancient Egypt impacted artists’ career trajectories and their aesthetics.

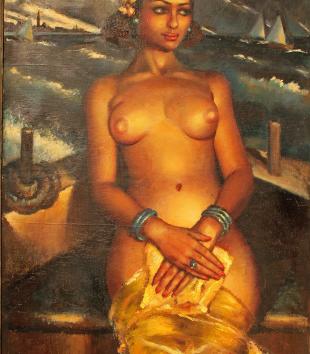

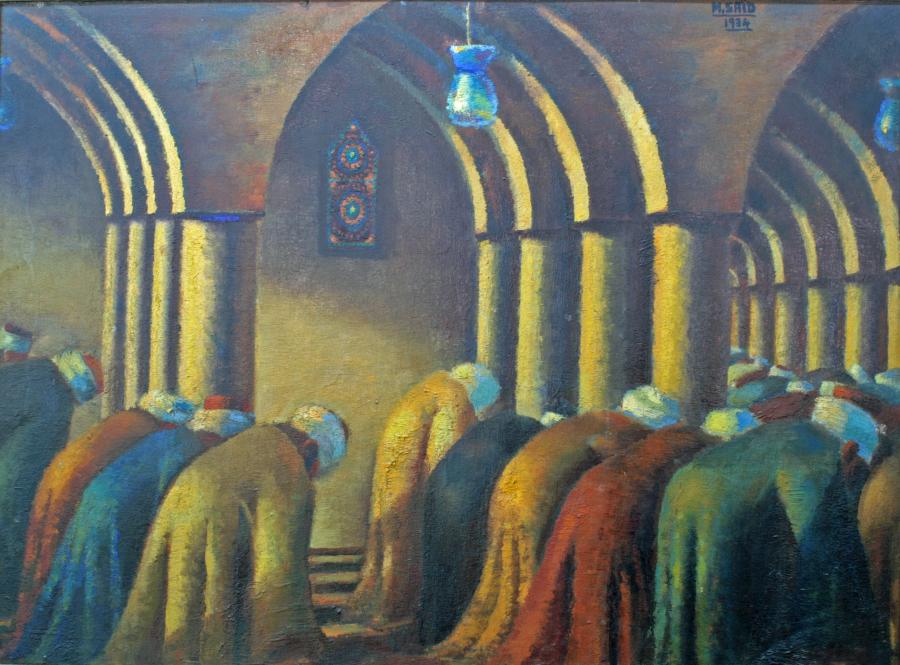

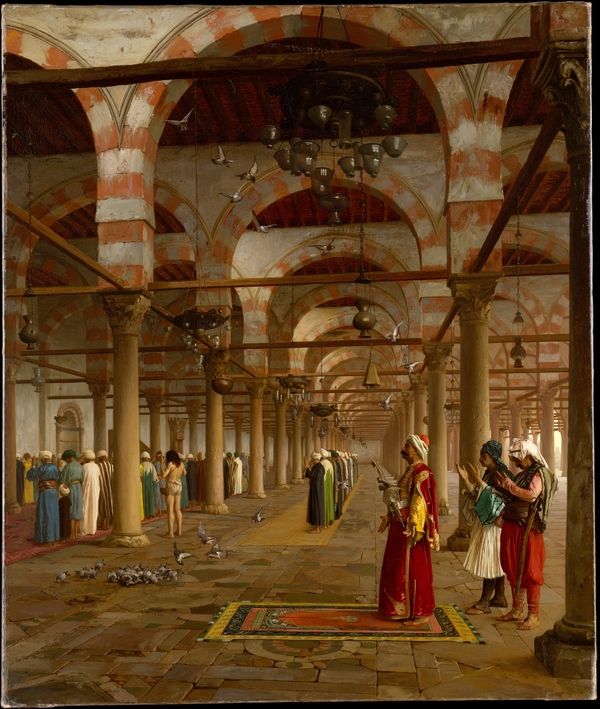

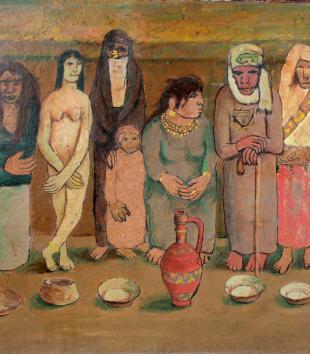

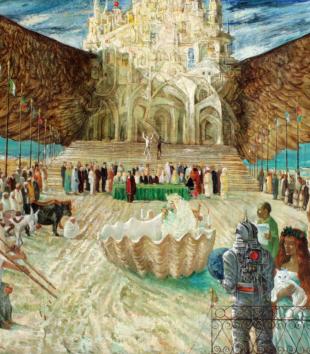

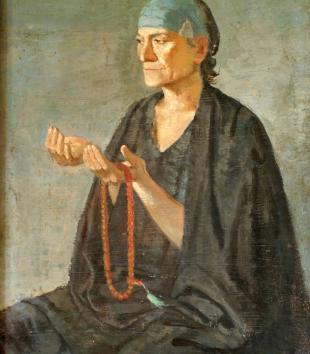

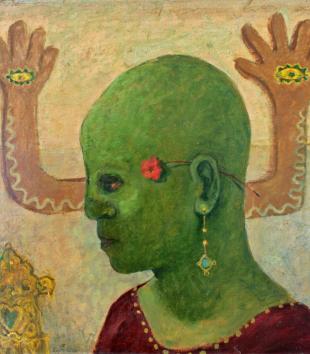

As I lay out in the book’s introduction, Islam was a factor, but not the defining factor, of modernism in Egypt. Often, it is expected that art from a predominantly Muslim country will be primarily concerned with religion, but this is not the case for Egyptian art in this era. Islam played an important, but not central, role in the Egyptian modernist art movement. Artists neither rejected nor enshrined religion—it was just one aspect of many in their artistic lives. The majority of the artworks presented in the book are non-religious in purpose, content, and execution. Moreover, the artists that I discuss were not particularly religious and many were avowedly non-religious in their writing and artworks. Although I evaluate these artists’ incorporation of issues related to Islam, religion, or spirituality, as relevant, often they were much more concerned with other social issues, from feminism to the space race, than they were with religion. Islam was only one of the many connections that Egyptian modernist artists acknowledged in their work.

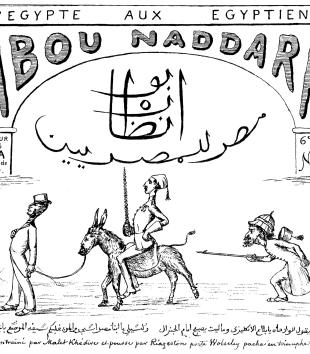

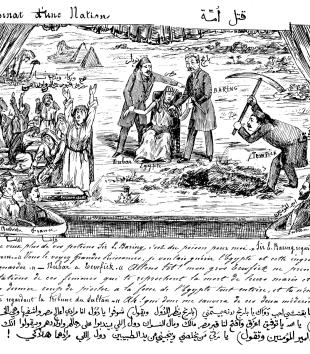

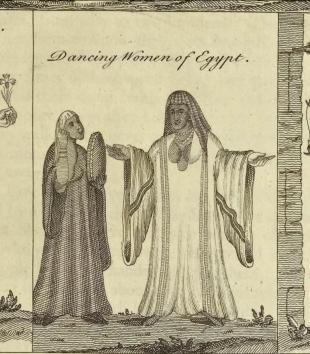

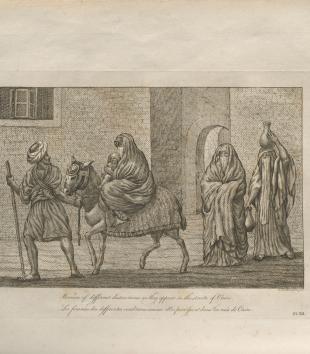

The history of global modernity is entangled with colonial histories, which continue to inculcate the identities of colonizer and colonized. The existing methodological approaches to non-Euro-American modernist art movements risk perpetuating colonial narratives. Many scholars have rightly challenged the view of modernism as solely Euro-American. However, expanding modernism’s geography does not sufficiently change the scope of modernism or redefine what modernism means. Instead, it risks contributing an additive, alternative story that upholds the paradigm of peripheral modernity. According to this conception of global modernism, non-western actors, such as Egypt, are understood as having a less central role in the creation of modernity than Europe. Moreover, many of these non-western actors, in fact, believed that modernity originated in the West. To challenge the problematic narratives of modernity, perpetuated by both traditional and emergent approaches to modernism, I develop a new paradigm through which I analyze Egyptian modern art. I call this new approach to global modernism “constellational modernism.”

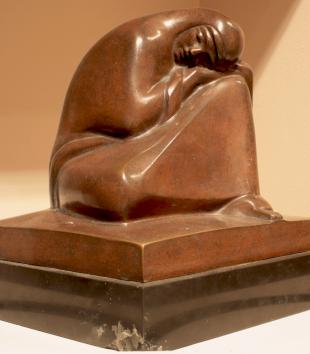

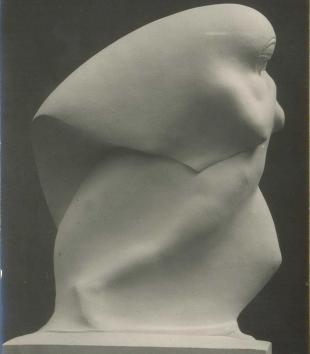

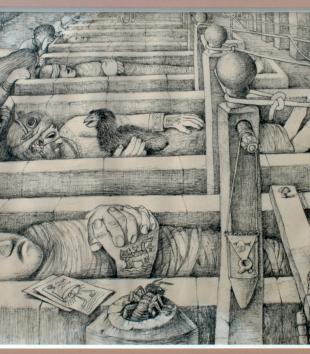

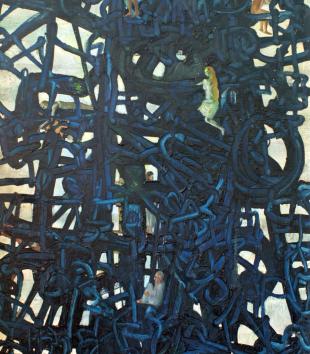

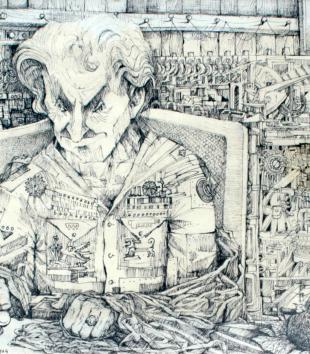

Constellational modernism more accurately describes the movement and aesthetics of Egyptian artworks than does a vision of a generalized, hyper-connected web of contemporary globalization. My approach builds on yet differs from Jessica Winegar’s ethnography of contemporary Egyptian art and Patrick Kane’s political framework for Egyptian modern art in that my method privileges the artworks and their aesthetics. Furthermore, rather than simply reflecting the social or political context of Egypt, I argue that these artworks and this art history are significant for all of global modern art history. Modern Egyptian art and artists circulated in distinct constellations, which encompassed finite local and transnational relations. The artists discussed in my book actively participated in global modernism, and as such were keenly aware of the dominance of European trends on the international art market. They were cognizant both of the competing histories of the French academic style in which most were trained, and of local Egyptian, Arab, and Islamic visual traditions. Their artworks visually map out a constellation of connections to diverse visual sources: embedded in the artworks’ aesthetics, they acknowledge and/or point to these references. The Egyptian sculptor Mahmoud Mukhtar exemplifies how Cairo and Alexandria’s modern artists circulated in distinct constellations. Born in Cairo in 1891, Mukhtar studied classical Greco-Roman sculpture at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Embedded into his sculptures are complex references to his Parisian training, Egyptian origins, and classical forms.

I dubbed this phenomenon “constellational modernism” because the constellation of connections I map for each artist and in each work is made up of a series of distinct and finite points, resembling the recognizable pattern of a celestial constellation. Constellational modernism also refers to the aesthetic characteristics that these connections make—not simply to the physical locations of movement, but also the way in which these references to diverse visual sources are imaged in the artworks. My hope is that other art historians and cultural theorists apply the concept of constellational modernism to other modernisms, both as a way to rethink the canon of modernism, and also to bring the diverse stories of global modernism into conversation with each other.

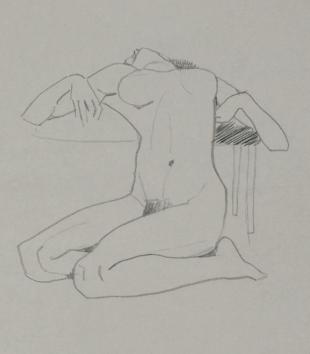

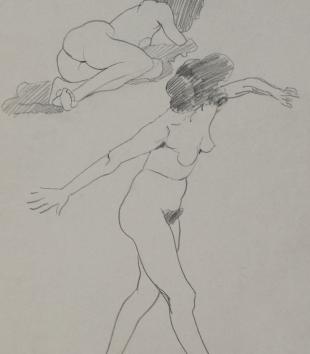

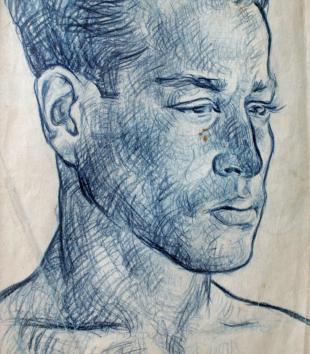

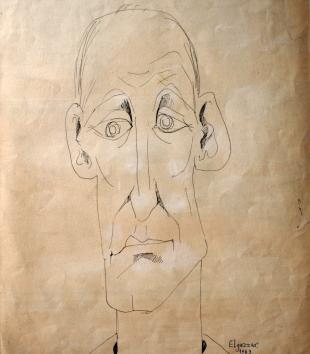

In what follows, I introduce and analyze a selection of artworks connected that are not included in the book, and elaborate on how these works relate to the overarching themes I have outlined above.