In 1802 Mary Lyman’s parents died and she was put under the guardianship of Bezaleel Howard, pastor of the First Church of Christ in Springfield, Massachusetts. Thereafter Mary attended a girls’ school in Boston where she completed a mourning piece, a type of needlework.1 The Rev. Howard displayed the mourning piece in his home and it attracted visitors from neighboring towns. Mary’s mourning piece served as visual and material evidence of her education, participation in mourning practices, and her religious and social formation.

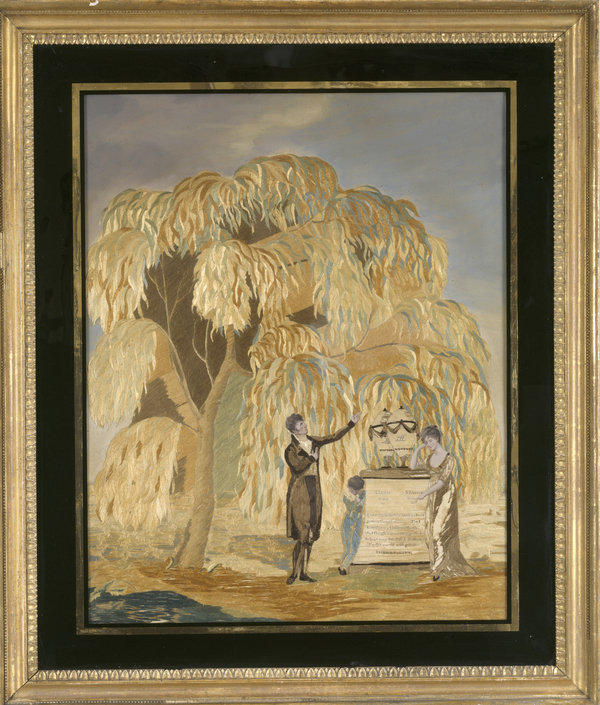

Abbey Wright, a schoolmistress from South Hadley, viewed Mary’s mourning piece and recorded her thoughts about it in a letter to her sister. In 1805 Wright wrote, “We called at the Rev. Mr. Howard’s…principally to see a piece of needlework lately executed at a celebrated school in Boston. It was an elegant piece and well executed…The piece I refer to was wrought by a Miss Lyman in memory of both her parents. It consists of a large willow, a monument and two urns, the figure of a lady and gentlemen and a little boy.”2 Mary’s mourning piece was a visual reference to a prestigious school in Boston. It also served as evidence of Mary’s training in accomplishments—needlework, good manners, taste, and refinement—which were expected of young women, particularly young women of means, at this time in American history.

Mary’s mourning piece also transmitted information about nineteenth-century mourning practices. The neoclassical funerary motifs in this piece of needlework, and others like it, inspired Mary’s contemporaries to feel and enact the specific sort of grief required in mourning. The figures signified the demeanor—solemn reverence and contemplation—and dress required of graveside mourners. But more than modeling proper demeanor and sartorial etiquette, the figures in the piece served as visual evidence that Mary and her brothers were Protestants who actively embraced these graveside practices. In all likelihood, then, the figures represent Mary and her brothers3 engaged in exemplary mourning behavior.

In her letter, Abbey Wright also suggested that Mary’s mourning piece was a memorial. It helped viewers do the cultural work of mourning in the comfort of domestic spaces. The funerary motifs and figures urged viewers to contemplate the elder Lymans’ deaths. Then, the figure of Mary directed viewers’ attention to the epitaph: “Leave thy fatherless children. I will preserve them alive. For I know that my Redeemer liveth. And though worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God. For this mortal must put on IMMORTALITY” (Jer. 49:11; Job 19:25-26; 1 Cor. 15:53). These bible verses asserted the Lymans’ Christian faith and assured viewers of the Lymans’ future resurrection. This assertion and assurance then encouraged viewers to contemplate their own mortality and life after death, making of the mourning piece a memento mori. This memento mori, however, suggested that belief was not enough for spiritual preparation. Mourners needed to participate in the visual culture of mourning through mourning pieces that directed the proper religious formation of viewers’ minds and bodies.

Mourning pieces were also expressions of wealth and social formation. Wright noted: “I have pieces in my school which I should not blush to compare with it if the expense of each might be admitted in the comparison. But people are not apt to do this…The expense of drawing and painting the faces [on Mary’s piece] was eight dollars and six months spent in Boston in working it. Comparing this with the labor of six or eight weeks in the country by a country girl without the assistance of a limner we might expect as great a contrast as we find.”4 Add to this expense Mary’s other materials: silk thread, silk satin ground, framing glass, and gilded frame.5 The time and money invested in the piece were essential to its production, display, and reception.

In 1917 Mary’s mourning piece came to the attention of historians when Isabelle Robinson found it in her attic in Dorchester, Massachusetts.6 Robinson wrote to William Appleton, founder of Historic New England,7 and noted, “As I have just sold our old Homestead built by my grandfather in 1757, I found an old, framed ‘mourning piece,’ dated 1802.” Robinson enquired, “Would it be of any value to the Society, if so I would gladly present it?”8 Appleton accepted the piece. It was stored in Maine from the 1930s to the 1980s when it was moved to storage in Boston. Needlework historian and author Betty Ring saw the piece in Boston in 1987 and connected it to Wright’s letter.9 Today, Mary’s mourning piece is stored at the Collections and Conservation Center in Haverhill, Massachusetts.10

Robinson’s question, “would it be of any value,” accentuates the multiple meanings attributed to mourning pieces in American history. Some nineteenth- and twentieth-century Americans treasured the pictures as family relics and material links to a personal past. Others consigned mourning pieces to family attics and forgot about them. Today, Americans consider the pieces to be collectibles. In 2012 Sotheby’s auctioned mourning needlework in Betty Ring’s collection for $2,250 to $62,500.11 The "value" of Mary’s mourning piece, and others like it, is multi-faceted. For Mary and her contemporaries, mourning pieces also derived value from their situation in the American tradition of visual display associated with nineteenth-century bourgeois Protestantism.

Notes

Notes

1. Betty Ring, Girlhood Embroidery: American Samplers & Pictorial Needlework, 1650-1850, Vol. I (New York: Alfred A. Knope, 1993), 80, 82-83, 85; Charles Wells Chapin, Sketches of the Old Inhabitants and Other Citizens of Old Springfield of the Present Century (Springfield, MA: Press of Springfield Printing and Binding Company, 1893), 259.

2. Abbey Wright Allen, Letter to her sister, 3 August 1805, in “Abbey Wright Allen: A Record of her Letters, etc., 1795-18442,” Microfilm at Mount Holyoke College Library, South Hadley, MA, 75-76.

3. Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 85, Fig. 83a.

4. Abbey Wright Allen, Letter to her sister, 3 August 1805, 76-77.

5.For other materials see: Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 80, 83; “Needlework Picture: GUSN: 27443,” Historic New England, Accessed September 26, 2012, perma.cc/0VpzRpcmeTd.

6. It is unclear how Mary’s mourning piece made its journey from Springfield. Genealogical evidence suggests it may have travelled with Mary’s children who settled in Dorchester. See entries for Mary’s children, Mary Lyman and Charles Emery, in Benjamin Woodbridge Dwight, The History of the Descendants of John Dwight, of Dedham, Mass, Vol. 2 (New York: John F. Trow & Son, Printers and Bookbinders, 1874), 945-46.

7. Then known as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.

8. Isabelle Robinson, Letter to William Appleton, 23 June 1917, Courtesy of Historic New England. Gift of Mrs. Isabelle H. Robinson, 1917.284.

9. Eleanor H. Gustafson, ed., “Collector’s Notes: Memorial Miraculously Materializes,” The Magazine Antiques, September 1988, 412; Ring, Girlhood Embroidery, 80, 82-83, 85.

10. Nicole Chalfant, e-mail message to author, September 19, 2012. I would like to thank Nicole Chalfant for all of her help in tracking Mary’s mourning piece and notifying me of Isabelle Robinson’s letter.

11. “Important American Schoolgirl Embroideries: The Landmark Collection of Betty Ring,” Sotheby’s, Accessed July 27, 2013, perma.cc/0J1arH5agzh. See Lots 538, 573, 580.

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.15

1. Jamie L. Brummitt, "Mary Lyman’s Mourning Piece," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.15

Brummitt, Jamie L. "Mary Lyman’s Mourning Piece." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.15