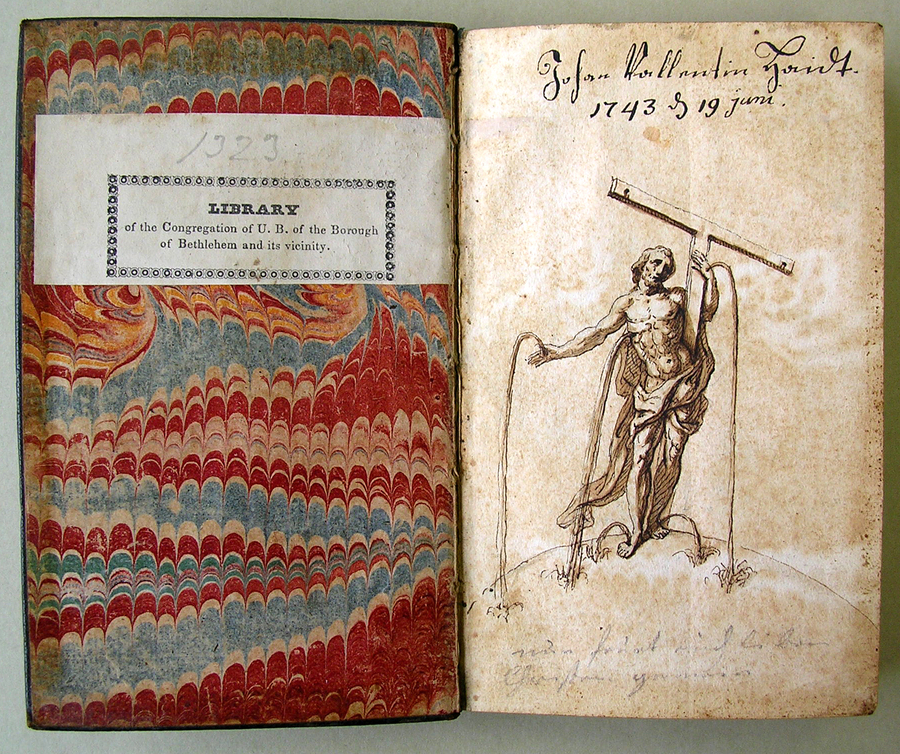

This is the only known drawing by John Valentine Haidt, the most important Moravian artist of the eighteenth century. It appears at the opening of a small black-leather-bound hymnal that belonged to Haidt, upon a sheet of paper lightly stained and speckled with rusty spots. The page is vertically oriented, with the statuesque body of a contrapposto Christ splitting the sheet into two equivalent halves. The artist inscribes his signature in heavy black ink at the top of the page, “Johan Vallentin Haidt,” with a date just below, “1743 19 juni.” Toward the bottom of the paper we see a hard-to-read notation in soft lead pencil (in another hand, probably applied later), perhaps a quotation from the writings of Martin Luther.1

Blood pours in bunched lines from Christ’s five wounds. It springs from his right hand in three long and wiggling lines and from his left in an even lengthier and steadier stream. It flows in tight arches from his feet and gushes forcefully from the dark slit of his spear-pierced right side. The arcs echo and intersect the similarly bowed and slightly sloping line below—a schematic representation of the earth—which spans the width of the page. The intersecting curves create small cross forms. The lines that figure the falling blood connect the colossal Christ and his image to the earth.

Christ’s singular image is distributed multiply across the globe. However paradoxically, Christ’s blood, an index of the trauma he experienced during the passion, buttresses his broken body. The forms spurting from his hands also call to mind the shepherd’s crook. The preponderance of unmarked space surrounding the image of Christ adds to the feeling of his singularity; he is the sine qua non of both existence and representation. He stands on top of a virtually featureless earth and marks it with his blood. In addition to the empty areas of the sheet, the lack of any indication of realistic location or narrative also signals Christ’s supra-contextualism.

Born in Gdansk, Prussia in 1700, as a young man Haidt studied drawing at the Royal Academy of Arts in Berlin. He later moved to England, where he worked as a goldsmith. While there he converted to Moravianism and began painting for the church, relocating in 1754 to the Moravian settlement in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where he lived until his death in 1780. Haidt was a lay preacher as well as a painter, though he concentrated on painting in the later part of his life. The Moravian tradition is rooted in a pre-Reformation-era reform that occurred in fifteenth-century Bohemia; a revival of this tradition, the modern Moravian Church originated in what is now Germany in the early eighteenth century, under the leadership of Nicolaus Ludwig, Count von Zinzendorf. The Moravians were actively involved in missionary work, with outposts ringing the Atlantic world, from mainland Europe to the Ohio frontier, from Greenland to West Africa and the Caribbean. Haidt supplied missions both near and far with oil paintings.2

In the eighteenth century the Moravians held a special devotion to Christ’s blood and wounds. Haidt’s other extant works are religious paintings or portraits of Moravian sitters, and the best-known of these all focus, like this drawing, on the bloodied and beaten body of Christ. Haidt’s drawing is directly related to late medieval and early modern fons vitae imagery, which depicts a bleeding Christ as the fountain of life. But the drawing is, more significantly, a summation of the role a Christocentric visual culture played in Moravian missionary practice during the eighteenth century.

A sinking resignation inflects Christ’s facial expression, the essential articulation of the classical body in pain. His eyes roll heavenward, a reference to the significance of vision for the Moravian Brethren, of sight as a sense that can bring God nearer. Christ’s eyes rotate upward and to the right, toward Haidt’s surname, connecting the source of bodily vision to the artist himself. Also of significance, Christ’s eyes look in the direction of the almost completed mathematical sign of infinity [∞] in the German script H in “Haidt.” Is Haidt suggesting that he approaches infinity or Christ through the making and distribution of pictures of him? Or, more radically, that Christ approaches infinity through Haidt’s pictorial constructions of him? This drawing is a kind of self-portrait of Haidt, or an image that summarizes his artistic practice. Haidt’s name at the top of the drawing, in a sense in its sky space, is allied with heaven, not the world. The name is an interlingual pun—the artist is here both “Haidt” and “height.”

The slanting beam of the tau-cross contains Christ. Haidt alludes to the strong relation of incarnational theology and Christian image theory by means of the conflation of the letter-form cross and Christ’s fleshy left side and leg. The leg eclipses the lower portion of the T, and the base of the T and Christ’s left foot come to rest upon the global arc in the same place. The Book of John (1:14) describes the coming of Christ: “the Word was made flesh.” This scriptural passage, above all others, was the key to explicating the permissibility of artistic representation in Christianity. The clever combination of letter and leg may also be a reflexive reference by Haidt to his own artistic practice, which he described as “preaching in pictures.” Haidt depicts Christ with an extended right arm, an oratorical posture important to classical sculpture. One might also read the upper section of the T as nesting in Christ’s side or issuing from it. In these ways, Haidt underlines the interdependence of word and image, and their twin embeddedness in the body of Christ.

Although Christ extends only one of his arms, he is nevertheless nearly a T. The two points on (representing holes in) his hands match the two points on (representing holes in) the cross. The letter and the body share a relative symmetry. The arms of Christ and the arms of the cross rhyme, and they stretch, to the left and right, toward the edges of the page. This extension is a bestowal, the sacrifice of Christ on the cross a reaching out to the world. Christ and the cross intertwine, and in conjunction they figure a large diamond, an evocation of the heavenly riches purchased for believers through his voluntary suffering and death.

Facing the drawing, the inside of the book’s cover bears marbled paper, which was made by pressing prepared paper on ink or paint floating in thickened water. It radiates and swirls in energetic waves of red, pink, orange, tan, and blue-green, and this abstract chromatic mixture speaks to the content of the drawing, in which the body and blood of Christ are spreading across the seas by means of the Moravian missionary project. The drawing is a missionary metapicture—an image about the place of corporate imaging in processes of early modern globalization. Indeed missionary imagery of the body of Christ in this era is the primary model from which the modern culture of the globalized corporate image is derived.

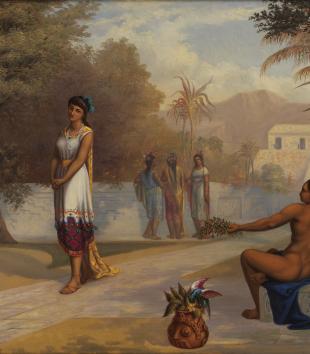

Haidt’s best-known composition, the Erstlingsbild (First Fruits), which exists in several versions dating to the late 1740s, dialogues remarkably with Coca-Cola’s famous “Hilltop” Ad of 1971.3 In both cases we find a corporate image (either the body of Christ or Coca-Cola) uniting people from all over the world. In the drawing, the streams of Christ’s blood are reminiscent of both liquid sweetness pouring from a soda fountain and McDonald’s golden arches. While the Moravians themselves may have viewed their missionary practice and its attendant image culture in the utopian terms of that well-known Coke jingle (“I'd like to buy the world a home and furnish it with love, / Grow apple trees and honey bees, / and snow white turtle doves. / I'd like to teach the world to sing in perfect harmony…”), the realities of the Moravian missions’ cultural effects were more akin to the violence figured in Cold-War-era nuclear ballistics diagrams—with their arcing missile paths crisscrossing the globe—which the drawing’s forms also peculiarly portend.4

The Moravian missionary project was predicated upon the dissemination of missile-like images of the body of Christ to distant locales. What the Moravian minister Johann Langguth writes to the Moravian painter Johann Jakob Müller in a birthday poem of 1744 might be said of all Moravian artists, including Haidt: “we only paint one Man, that piece is indeed the best / … / [a]nd wherever possible we try to eradicate the other pictures.”5 The places where Christ’s blood impacts the ground in the drawing, choppily rendered and short and scraggly, evoke the clouds of dust and debris that accompany a disordering act of destruction. Like today’s globalized corporate image, the missionary image constructs a fantasy of cultural concord but is an instrument of cultural discord. Haidt’s drawing dreams of a totalized Christian civilization while at the same time indexing the militant cultural imperialism of Moravian missionary activity.

Notes

Notes

1. I thank Paul Peucker for pointing this out to me.

2. For a newly published treatment of Haidt’s life and work, see Vernon H. Nelson, John Valentine Haidt: The Life of a Moravian Painter, ed. June Schlueter and Paul Peucker (Bethlehem, PA: Moravian Archives, 2012).

3. On Haidt’s Erstlingsbild, see perma.cc/0HbxkVs6out. On Coca-Cola’s “Hilltop” Ad, see perma.cc/0Nb3XhW3qyH.

4. For one such diagram, see perma.cc/0nE9Xt2S5NF.

5. Johann Langguth, quoted in Paul Peucker, “A Painter of Christ’s Wounds: Johann Langguth’s Birthday Poem for Johann Jakob Müller, 1744,” in The Distinctiveness of Moravian Culture: Essays and Documents in Moravian History in Honor of Vernon H. Nelson on his Seventieth Birthday, ed. Craig D. Atwood and Peter Vogt (Nazareth, PA: Moravian Historical Society, 2003), 28.

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2014.4

1. Jason David LaFountain, "John Valentine Haidt, Christ with a tau cross standing on top of the world and bleeding from his five wounds," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.4

LaFountain, Jason David. "John Valentine Haidt, Christ with a tau cross standing on top of the world and bleeding from his five wounds." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2014.4