Object Narratives explicate religious images, objects, monuments, buildings, or spaces in 1500 words or less.

Object Narratives

A special issue guest edited by Kambiz GhaneaBassiri and Anna Bigelow.

Ayat Al Kursi Round

Ayat Al Kursi Round

Crowned by the word “Allah,” a dense piece of Arabic calligraphy carved out of stainless steel wraps around an embellished center. The text is the ayat al-kursī, or “The Throne Verse,” a portion of the Qur’an (2:256) often recited before sleep or travel because of its reputation for spiritual and physical protection. While the Illinois-based company Modern Wall Art produces the above “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” at least six other businesses manufacture their own ayat al-kursī pieces in the same circular visual style. These pieces of Islamic decor appeal to different tastes in spite of the repetitiveness of their visual content. By attending to the specific production method and branding of “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” we can identify how the materialization of God’s words in wall art entangles Islamic ethics and the aesthetics of class formation.

The Black Cross

The Black Cross

Donald Jackson’s The Black Cross illustrates some of the ways contemporary calligraphic art engages sacred writ: through the interplay of word and image, recording the artist’s physical gestures, and making visible the divine.

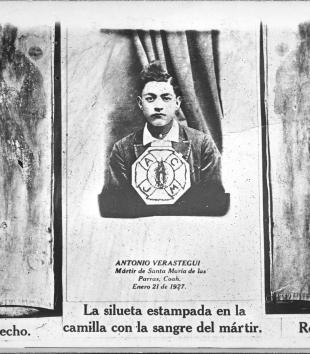

Photographic Postcard Commemorating Antonio Verástegui

Photographic Postcard Commemorating Antonio Verástegui

A postcard commemorating a young “martyr” of Mexico’s Cristero War named Antonio Verástegu engages the spectator in an act of witnessing that entails both religious and political consequences.

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Eve Hearing the Voice

Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Eve Hearing the Voice

In 1876, Moses Jacob Ezekiel, the first Jewish American artist of international stature, sculpted the world’s first woman, to which he gave the title, Eve Hearing the Voice.

Mural Paintings, Church of the Summer Residence of the Maronite Patriarch, Diman

Mural Paintings, Church of the Summer Residence of the Maronite Patriarch, Diman

Since its construction around the turn of the twentieth century, Our Lady of Diman has served as the summer residence of the Maronite Catholic Patriarch. The prestige of the building is everywhere apparent: in the inlaid marble floor, in the gold and blue panes of the stained-glass windows. The church’s most remarkable feature, however, is the ceiling over its nave, with frescoes completed in the late 1930s by celebrated Lebanese painter Saliba Douaihy (1913-1994).

A Stick of Wood, a Tree of Life

A Stick of Wood, a Tree of Life

This Ets Chayim, a Tree of Life, is obsolete, redundant, out of time and out of place. It is detached both from the Torah scroll for which it was made, and from its mate that once served that scroll’s other end. It is not supposed to be here anymore—here, that is, in a transformed, glass-sheathed, twenty-first-century Lower East Side, where the traces of immigrant life have been erased, sanitized, and gathered into museums, or commodified as “atmosphere” for an urban playground. Perhaps the act of marking it—noting its persistence beyond obsolescence, shorn of the text to which it was once an auxiliary, bereft of the hands that once grasped it and the congregation that once stood as it was lifted up—is a minor act of resistance in itself.

Fernando Brito and Héctor Parra, Judío

Fernando Brito and Héctor Parra, Judío

In Judío, photographer Fernando Brito attempts to find an ad-hoc visual representation for the Yoremem or Mayo Indians in his native state of Sinaloa, Mexico. This portrait pays tribute to the foundational value of the community’s ritual, which combines indigenous cosmology with seventeenth-century Jesuit influence, as crucial to its survival and cohesion.

A Dying House in Samarkand’s Jewish Neighborhood

A Dying House in Samarkand’s Jewish Neighborhood

Pagiel Leviyev’s house is very sick. Built in Samarkand over a century ago, the structure was designed as a mansion for a wealthy mercantile family. Today, it stands as a crumbling reminder of the Jewish community’s long and complex history in this unexpected spot of the world.

Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect

Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect

In The Resolution of the Suspect, photographer Miki Kratsman builds on the reliquary nature and the transitive qualities of the carte-de-visite, creating a diptych: the historic image on one page of the centerfold and his own photograph of the bloody garment of a single unnamed Palestinian martyr on the other.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Cross with Stars and Blue

Georgia O’Keeffe, Black Cross with Stars and Blue

In 1929, on her first visit to New Mexico, the American artist Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986) observed the animate potential of the region’s religious material culture.

MAVCOR began publishing Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion in 2014. In 2017 we selected a new name, MAVCOR Journal. Articles published prior to 2017 are considered part of Conversations and are listed as such under Volumes in the MAVCOR Journal menu.

An American Sufi Shrine, Bawa’s Mazar in Coatesville, Pennsylvania

An American Sufi Shrine, Bawa’s Mazar in Coatesville, Pennsylvania

An ethnically and religiously diverse spiritual community near Philadelphia founded by a Tamil teacher from Sri Lanka.

From Illuminated Rumi to the Green Barn: The Art of Sufism in America

From Illuminated Rumi to the Green Barn: The Art of Sufism in America

The role material culture has played in the introduction of non-Christian forms of spirituality into the United States as examined through Sufi art.

Virtual Meditation Cushion (Zafu)

Virtual Meditation Cushion (Zafu)

What does a virtual meditation cushion tell us about material and visual cultures of religion?

Ex-Votos, Shrine of St. Roch, New Orleans

Ex-Votos, Shrine of St. Roch, New Orleans

Ex-votos at the Shrine of St. Roch occupy a complex place within conceptions of New Orleans as the subject of Protestant fascination with exoticized material aspects of Catholic practice.

Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt

Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt

The carte-de-visite of Maximilian von Habsburg’s shirt satisfied a sensational interest in the political event and served as a mourning object, offering the living both visual and tactile connections to the deceased to aid in the grieving process.

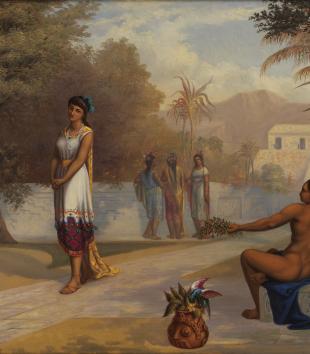

George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden

George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden

Utah artist George Martin Ottinger painted Aztec Maiden during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when numerous theories proliferated about the history and origins of indigenous American civilizations.

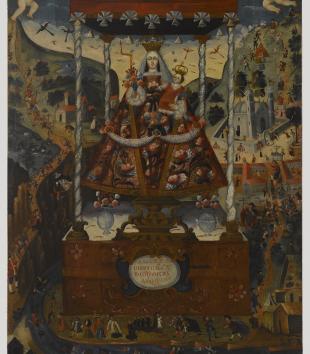

Our Lady of Cocharcas

Our Lady of Cocharcas

Material objects, including a group of documentary paintings of Our Lady of Cocharcas, recall the processes by which ancient Andean pilgrimage traditions became deeply integrated into late-colonial socio-religious consciousness.

Mask with Superstructure Representing a Beautiful Mother (D'mba)

Mask with Superstructure Representing a Beautiful Mother (D'mba)

What is the meaning of the word "spirit" in Africa?

William Vander Weyde, Leon F. Czolgosz, McKinley Assassin

William Vander Weyde, Leon F. Czolgosz, McKinley Assassin

Early debates around the use of the electric chair pivoted on the convergence of state and divine power.

The Balvanera Escudo

The Balvanera Escudo

Nun's badges worn in colonial New Spain not only articulated a woman’s religious affiliations, family fortune, and ethnic purity but also expressed her desire to influence political opinion.

Adonai/Adidas T-Shirt

Adonai/Adidas T-Shirt

The t-shirt’s appropriation of a multinational sportswear corporation’s logo into a sacred Hebrew name for God could be simply a clever play on words, but a more critical approach might take into account the commodification of this sacred name for the deity and its subsequent selling in the marketplace for profit.

C. C. A. Christensen, Joseph Preaching to the Indians

C. C. A. Christensen, Joseph Preaching to the Indians

Although LDS doctrine esteemed Native Americans as literal descendants of the peoples of the Book of Mormon, relations between Mormons and Indians in Utah grew increasingly strained as resources became scarce. Christensen’s work reflects this divided perspective.

Portable Altar of Countess Gertrude

Portable Altar of Countess Gertrude

The portable altar seems to have developed in the missionary world of the seventh century, to meet the Church's requirement that Mass be celebrated only on a consecrated altar—a requirement that strengthened the position of bishops, who alone could consecrate them.

Thomas Eakins, The Crucifixion

Thomas Eakins, The Crucifixion

In his 1880 The Crucifixion, Thomas Eakins, a reputed agnostic, crafted a realist interpretation of one of the central devotional subjects in Christian art, challenging the traditional iconography of the crucifixion by eliminating all signs of divine presence.