Lucy O'Sullivan is a Lecturer in Latin American Studies at the University of Birmingham. Her first book, entitled Diego Rivera and Juan Rulfo Post-Revolutionary Body Politics 1922-1965 is forthcoming with Legenda. Her current research centres on visual production relating to Mexico's Cristero conflicts and the Sinarquista movement.

Fig. 1 Photographic postcard commemorating Antonio Verástegui, created by the Asociación Católica de la Juventud Mexicana (Catholic Association of Mexican Youth) undated, Gelatin silver on paper, black and white. Size: 5.5 x 3.5 in (13.97 x 8.89 cm) IISUE/AHUNAM/Fondo de Aurelio Robles Acevedo/ Sección: Asociacion Catolica de la Juventud ACJM/ARA-0126.

This postcard (Fig. 1) commemorates a young “martyr” of Mexico’s Cristero War (1926-1929) named Antonio Verástegui and the miraculous contact relic associated with his death. When in 1926 President Plutarco Elías Calles introduced a penal code enforcing the anticlerical provisions of Mexico’s revolutionary constitution of 1917, the Catholic hierarchy suspended religious services across the country in protest and a national revolt was called by an umbrella body of Catholic lay organizations known as the Liga Nacional Defensora de la Libertad Religiosa (National League for the Defense of Religious Liberty - LNDLR). The resulting confrontation between federal forces and Catholic activists, whose battle cry of “Long live Christ the King!” (“¡Viva Cristo Rey!”) inspired the originally pejorative epithet of “Cristeros," devastated Mexico’s central-western states and seriously threatened the stability of the nascent regime. Religion was an important factor motivating Catholics to take up arms against the state and they relied on religious symbols and structures to articulate their activism.1 Cristero fighters set out for combat carrying scapulars, rosaries, and flags of the Virgin of Guadalupe and Christ the King and compared their plight to the earliest persecuted Christians, framing Calles as a tyrannical, modern-day Nero.2

Verástegui was a member of the Asociación Católica de la Juventud Mexicana (Catholic Association of Mexican Youth - ACJM), a lay Catholic organization founded by the French Jesuit Bernardo Bergöend in 1913 that later operated under the LNDLR. Post-revolutionary anticlericalism fostered the radicalization of this youth movement during the 1920s and in 1926 its members answered the League’s call for armed rebellion.3 Verástegui participated in the first waves of military action initiated by the ACJM in Coahuila and was executed in the town of Santa María de las Parras on January 21, 1927 at the age of just sixteen.4 In this commemorative postcard, likely produced between 1927 and 1929, a central portrait of Verástegui displaying the ACJM logo on his chest is flanked by two photographs depicting stained sheets of cloth. Although its specific origin is unknown, the image of Verástegui neatly dressed and groomed against a curtain background was likely produced for an ACJM membership card. Verástegui’s youthful appearance contrasts sharply with the spectral quality of the death shroud presented in the two accompanying photographs. A caption in the lower part of the composition states that these images depict “the outline imprinted on the stretcher by the martyr’s blood.” According to a handwritten note also held in the AHUNAM archive in Mexico City, these photographs display the cloth used to carry Verástegui’s corpse which miraculously retained the blood-stained impression of his body after it was washed. It claims that the textile was preserved as a relic by Verástegui’s grandfather and visited by over three thousand pilgrims.5

- 1Matthew Butler underlines the Cristeros’ religious commitment, while acknowledging other motivating factors such as ethnicity, land ownership, and other economic considerations. Jennie Purnell emphasises political and material motivators such as the defence of traditional forms of land tenure against post-revolutionary agrarian policies. Matthew Butler, Popular Piety and Political Identity in Mexico’s Cristero Rebellion: Michoacán, 1927-29 (New York: British Academy and Oxford University Press, 2004); Jennie Purnell, Popular Movements and State Formation in Revolutionary Mexico: The Agraristas and Cristeros of Michoacán (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999).

- 2Julia G. Young, Mexican Exodus: Emigrants, Exiles, and Refugees of the Cristero War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 27.

- 3David Espinosa, “‘Restoring Christian Social Order’: The Mexican Catholic Youth Association (1913-1932),” The Americas 59, no. 4 (2003): 459.

- 4Asociación Católica de la Juventud Mexicana, Fondo Aurelio Robles Acevedo, Archivo Histórico de la UNAM.Cabinet 2, File 8, Document 125.

- 5Ibid.

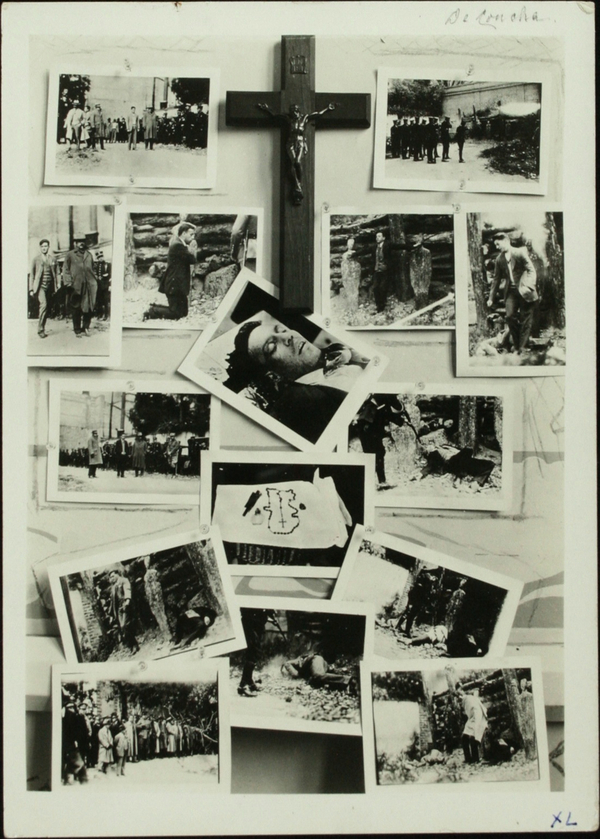

Along with this contextual information, the postcard provides insight into the first decades of the twentieth century in Mexico as a phase of religious as well as sociopolitical upheaval. While anticlericalism generated new forms of militant Catholicism, the closure of churches encouraged lay actors to embrace experimental modes of piety such as spontaneous peregrinations to sites of purported miracles and unofficial martyr cults.1 Lay Catholic organizations such as the ACJM not only diverged from canonical definitions of martyrdom by venerating militant Catholics but also adapted methods of martyr memorialization to the age of mechanical reproduction. During the conflict and its aftermath, photographs of Cristero “martyrs” circulated widely in Mexico, the United States and Europe.2 These images, which ranged from funerary-style photographs of dead priests and combatants lying in repose to graphic portrayals of executions and mutilated corpses served an important religious purpose by establishing an audience for the suffering of these martyrs while also functioning as sensational forms of anti-state propaganda.3 The most durable example of this photographic tradition relates to the Jesuit priest Miguel Pro who was executed in 1927 for his alleged involvement in a plot to assassinate former president Álvaro Obregón. The photograph of Pro with his arms outstretched in the form of the crucifix as he faced the firing squad remains the defining image of the conflict and is still sold as a collectable print at the Sagrada Familia Church in Mexico City where his shrine is located. A photograph held at the CEHM Archive in Mexico City dating from 1927 shows this iconic image of Pro (located to the right of the crucifix’s shaft) and other martyr photographs assembled in the form of a makeshift altar, confirming that they possessed a strong devotional value. It is important to acknowledge however, following Matthew Butler, that religion and revolution were not “monolithic and irreconcilable” concepts, but were rather interlinked in complex ways.4 Just as Catholicism was “revolutionized” as a result of these decades of conflict, revolutionary action often assumed sacred dimensions.5 Emiliano Zapata, who was also posthumously celebrated as a martyr, led his soldiers into battle under Guadalupan banners and post-revolutionary politicians frequently appropriated religious concepts to articulate their transformative societal vision.6

- 1Matthew Butler, “Trouble Afoot? Pilgrimage in Cristero Mexico City,” in Faith and Impiety in Revolutionary Mexico, ed. Matthew Butler (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008), 149-163.

- 2As with most martyr images, the geographical circulation of this postcard is poorly documented. We know however that other images memorializing Verástegui preserved in the AHUNAM archive were printed in Barcelona. Others are held in the Knights of Columbus archive in New Haven, Connecticut.

- 3As Tessa Rajak explains, martyrdom “demands a public, a response, and a record. In the Christian tradition, the terminology itself is a clue, for the deaths of the martyrs bear witness (martureisthai) to their faith in front of an assumed audience immeasurably greater than the immediate one at the scene.” Tessa Rajak, “Dying for the Law: The Martyr’s Portrait in Jewish-Greek Literature,” in Portraits: Biographical Representations in the Greek and Latin Literature of the Roman Empire, ed. Mark J. Edwards and Simon Swain (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997), 40.

- 4Matthew Butler, “Introduction: A Revolution in Spirit? Mexico, 1910–40,” in Faith and Impiety in Revolutionary Mexico, 2.

- 5Butler, “Introduction: A Revolution in Spirit? Mexico, 1910–40,” 11-18.

- 6For historical context on the mobilization of the Virgin’s image for political purposes, see Jeanette Favrot Peterson, “The Virgin of Guadalupe: Symbol of Conquest or Liberation?,” Art Journal 51 (1992): 39-47. An example of the iconography that developed around this revolutionary martyr cult is Diego Rivera’s mural Blood of the Revolutionary Martyrs Fertilizing the Earth (1927) at the National School of Agriculture at Chapingo. On the use of religious metaphors to visually articulate the redemptive nature of post-revolutionary educational and agrarian reform, see Lucy O’Sullivan, Diego Rivera and Juan Rulfo: Post-Revolutionary Body Politics 1922-1965 (Cambridge: Legenda, forthcoming), 159-204.

The postcard dedicated to Verástegui belongs to a rarer variety of martyr image that communicates martyrial sacrifice through the presentation of a relic, rather than a corpse or execution scene.1 The image encapsulates the religio-political concerns of the ACJM, functioning as both a form of contact relic and a piece of visual propaganda. Verástegui’s bloodstained textile evokes a long-standing Christian tradition of contact relics bearing miraculous bodily imprints dating back to the Turin Shroud, St. Veronica’s veil and, most notably in the Mexican context, the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe (Fig. 3) who appears in the ACJM logo at the center of this composition. According to the legend, when Mexico’s first archbishop Juan de Zumárraga demanded that the Nahua shepherd Juan Diego provide proof of the Virgin’s apparition on the hill of Tepeyac in 1531, she projected her luminous image onto the peasant’s tilma (cloak). The photographs of Verástegui’s burial shroud serve a comparable function by authenticating a miraculous event. The forensic quality of these grainy close-up photographs and the captions identifying the “front” and “rear” views of its surface underline their evidentiary purpose, encouraging the viewer to read the photograph as a mechanically produced “vera icon.”2 In harnessing the medium’s documentary power to register death, these photographs recall the grisly images of executions, mutilated corpses, and remnants of war that circulated in the illustrated press and in postcard form during the revolution as proof of the conflict’s latest casualties. Particularly striking comparisons can be drawn between the content and testimonial purpose of the postcard’s imagery and a photograph of Agustín Víctor Casasola and other photojournalists holding forth the blood-stained clothing of the recently assassinated Francisco Madero and José María Pino Suárez in February 1913.3 As in the case of acheiropoieta (images not crafted by human hands) such as the Guadalupan tilma, the photograph’s claim to authenticity derives from the assumption that it is produced by the indexical agency of light rather than the creative intervention of an artist. In El guadalupanismo mexicano (1953), art historian Francisco de la Maza explicitly compared the creation of the Guadalupana to the photo-chemical process of photography (literally “drawing with light”), likening the Virgin to a camera and Diego’s cloak to film.4

- 1Another example of this variety of martyr image is a photograph depicting the perforated heart of José de León Toral, another ACJM member who was sentenced to execution in 1929 for assassinating Álvaro Obregón.

- 2In its photographic imagery and dual functions as relic-like memento and evidentiary document, this postcard powerfully recalls the Carte-de-visite photograph depicting the execution shirt of Maximilian von Habsburg who ruled as Emperor of Mexico between 1864 and 1867. See Eleanor A. Laughlin, “Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt,” Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016), doi:10.223322/con.obj.2016.1.

- 3Laura Levitt suggests that such evidentiary traces which are “bound up in visceral bodily connections” and offer testimony to violent traumas already function in a manner akin to contact relics. Laura Levitt, The Objects that Remain (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2020), 4. On the relic-qualities of this photograph from the Casasola archive and that of Maximilian’s execution shirt, which is specifically mentioned by Levitt, see Andrea Noble, Photography and Memory in Mexico: Icons of Revolution (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2010), 90-91. On photography and the Mexican Revolution, see also Olivier Debroise, Mexican Suite: A History of Photography in Mexico (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2001) and John Mraz, Photographing the Mexican Revolution: Commitments, Testimonies, Icons (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2012).

- 4Francisco de la Maza, El guadalupanismo mexicano (Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1953), 58.

The indexical and metonymic aspects of the relic find a parallel in the ontological condition of the photograph which has been conceptualized by theorists as an “emanation” or “material vestige” of its referent.1 This perception of the photograph as a conduit of presence underlay ritual uses of post-mortem photographs in Mexico, as in other parts of the world, during the nineteenth century. In the case of the ACJM image, the impression of physical contact generated by the indexicality of the photographs is enhanced by the material form of the postcard which demands an intimate form of looking mediated by touch. As Martin Lister explains, physical photographic images are “as important to hold, touch, feel and check as it is for us to see, and which we sense has literally touched something that exists but is absent or has existed but is no more.”2 In the commemorative postcard, the viewer’s perception of the image as a point of contact with the shroud, and by extension, the martyr’s body, is encouraged by the prominent photographs of the cloth, which activate the form of haptic visuality conventionally associated with pictorial representations of celebrated acheiropoieta. This multisensory form of visual perception is exemplified in paintings such as such as Francisco de Zurbarán’s La Santa Faz (1631) (Fig. 4), where the use of chiaroscuro and the accentuated volume of the drapery create a trompe l’oeil effect that blurs the boundaries between vision and touch. Similar optical-tactile qualities can be detected in the photographic components of the postcard. The creased, uneven quality of the bloodied cloth, combined with the exaggerated folds of the half-drawn curtain behind Verástegui, encourage a similar visual association between the surface of the postcard and the textures of fabric that invite the beholder to engage with this visual object as a material trace of the absent martyr.3

Attention to these visual and tactile features sheds light on how the postcard functions as a form of contact relic and, by extension, its powerful affective appeal as a form of political propaganda. This visual artifact works within familiar iconographic frameworks of devotional experience but also exploits the particular capacity of photographic tactility to “participate in and create relationships and communities,” as Margaret Olin has shown.4 Given its postcard design, this portable image was likely intended to be passed from hand to hand, establishing a physical chain of contact not just between beholder and absent martyr but also with other viewers, creating an imagined community of witnesses connected through shared experiences of vision and touch. Beholding (a verb which, as David Morgan notes, captures this intimate connection between sight and touch) this postcard engages the spectator in an act of witnessing that within the Christian tradition inevitably entails both religious and political consequences.5 By creating an audience for Verástegui's suffering, the image looks to consolidate and legitimize this unofficial martyr cult but also, following Tertullian’s maxim “the blood of the martyrs is the seed,” to foster community bonds and perhaps even inspire imitation of his exemplary sacrifice.

- 1Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photograph, trans. Richard Howard (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 81; Susan Sontag, On Photography (London: Allen Lane, 1978), 154.

- 2Martin Lister, “Photography in the Age of Electronic Imaging,” in Photography: A Critical Introduction, ed. Liz Wells (London: Routledge, 2004), 332.

- 3Citing Graham Smith, Levitt notes a link between the metonymic function of Maximilian’s execution shirt and the habit of the martyr depicted in Zurbarán’s The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion. Levitt, “Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect,” Object Narrative, in MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018), doi:10.223322/mav.obj.2018.

- 4Margaret Olin, Touching Photographs (Chicago: University of Chicago, 2011), 17.

- 5Rubén Rosario Rodríguez, Christian Martyrdom and Political Violence: A Comparative Theology with Judaism and Islam (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 5; David Morgan, The Embodied Eye: Religious Visual Culture and the Social Life of Feeling (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 111.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2021.7

1. Lucy O’Sullivan, "Photographic Postcard Commemorating Antonio Verástegui," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), 10.22332/mav.obj.2021.7.

O’Sullivan, Lucy. "Photographic Postcard Commemorating Antonio Verástegui," Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), 10.22332/mav.obj.2021.7.