Samantha Baskind, Professor of Art History at Cleveland State University, is the author of five books on modern Jewish art and culture, and co-editor of The Jewish Graphic Novel: Critical Approaches. She served as editor for U.S. art for the 22-volume revised edition of the Encyclopaedia Judaica and is currently series editor of Dimyonot: Jews and the Cultural Imagination, published by Pennsylvania State University Press.

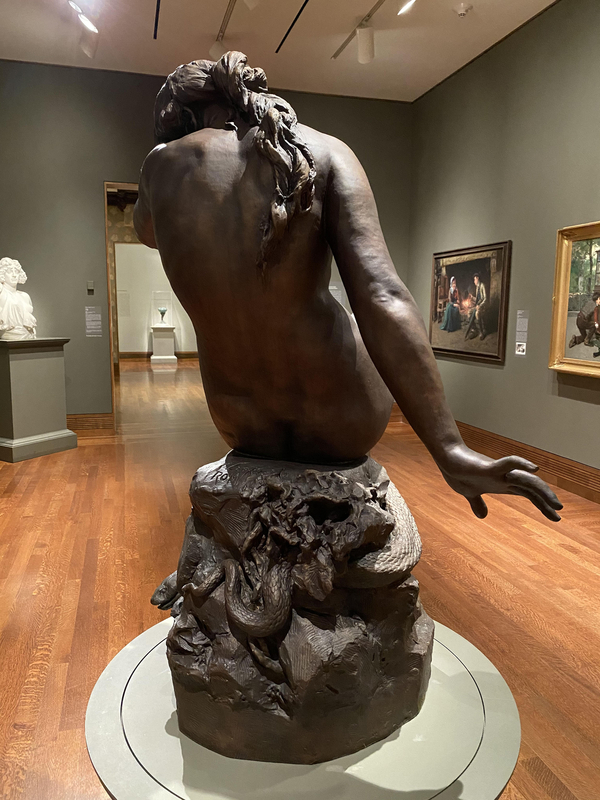

In 1876, Moses Jacob Ezekiel (1844-1917), the first Jewish American artist of international stature, sculpted the world’s first woman, to which he gave the unconventional title, Eve Hearing the Voice (Fig. 1). This life-sized bronze portrays a nude Eve after she has been tempted by the serpent, eaten from the Tree of Knowledge, and at the moment she suffers God’s rebuke. The naturalistically modeled Eve theatrically averts her head and painfully attempts to hide her face in the crook of her left arm, which partially covers her bare chest. She crosses her legs awkwardly, attempting to conceal her nudity. At Eve’s feet, the serpent coils menacingly around the rock upon which she cowers, and Eve’s bowed head looks downward at her tempter. Ezekiel took great care to delineate the textures of the serpent’s scales, just as he lavished attention on the thick hair that cascades gracefully down Eve’s muscled back and spirals over her face, down to her left breast (Fig. 2). These details, and Eve’s palpable despair, obscure the most novel feature of the sculpture: Ezekiel fashioned Eve, the only female nude he ever produced, without a navel.1

- 1For a short but excellent exhibition catalogue, with the most analytic assessments of Ezekiel to date, see Alice M. Greenwald, ed., Ezekiel's Vision: Moses Jacob Ezekiel and the Classical Tradition, exh. cat. (Philadelphia: National Museum of American Jewish History, 1985). See also David Philipson’s dated but crucial article, “Moses Jacob Ezekiel,” Publications of the American Jewish Historical Society 28 (1922): 1-62.

To convey a sense of Eve’s distress in the garden when her sinful act was revealed before God, Ezekiel enlisted her entire body. Less interested in classical stillness and more in the emotional and physical implications of Eve’s fateful choice, Ezekiel’s sculpture engages viewers, asking them to put themselves in Eve’s place, to imagine the unbearable regret of her impulsive act, and to suffer its consequences. Ashamed, she collapses into herself, unable to look toward the heavens. And then there is the missing navel. While conceiving Eve, Ezekiel turned to a close reading of the biblical text, which states that God fashioned Eve from one of Adam’s ribs. In his memoir, Ezekiel deliberately chronicles a conversation with a visitor to his studio about why he sculpted Eve as such: “I had made my Eve without an umbilicus. . . . it was very natural to do so since Eve wasn’t born, but created directly from one of Adam’s spare ribs.”1 An early clay model in Ezekiel’s studio shows her with a navel, the crucial element that he discarded (Fig. 3). The absence of the navel reminds the viewer that Eve is unlike us. She is not a woman with parents and a family. She is the first woman and she has no mother. All Eve has is Adam and God, both of whom she betrayed, and the snake who she trusted, but who she now realizes betrayed her as well. The missing umbilicus is part of the dramatic story that Ezekiel tells in bronze.

No critic has pointed out or commented on Eve’s nonexistent navel nor the sculpture’s inventive title. Doing so sheds light on an unexpected variation of a popular theme in the history of western art, precipitated by the artist’s engagement with the original source – compelled by the strength of his observant Jewish upbringing.

Nineteenth-century sculptors, American and otherwise, also favored Eve as a subject, for the emotional possibilities of her story and the freedom to depict a female nude in a socially acceptable way. Unilaterally, these sculptors included her navel, as did most painters.2 Especially celebrated for his neoclassical statue The Greek Slave (first version 1844), which toured the United States to high acclaim, Hiram Powers labored over and reworked his conceptions of Eve for years. Eve Tempted (modeled 1839-42, carved 1873-77) and Eve Disconsolate (Fig. 4) show Eve at two pivotal moments: when she prepares to eat the forbidden fruit and her reaction after she has been castigated by God. Powers’ delicate Eve Disconsolate is quiet in its reflective sorrow compared to Ezekiel’s dramatic, less idealized bronze, a function of the differing medium as well as presentation. Indeed, Powers’s sculptures of women were idealized, an interpretation Ezekiel resisted in favor of one that he hoped would show Eve, he wrote, as “perfectly human.”3

As a fellow American expatriate in Italy, Ezekiel very well may have visited Powers’s Florence studio and viewed versions of Eve there. At the very least, he was likely to have seen photographs of them, and perhaps even heard about the sculptures from friends in Cincinnati, the city from which Powers stemmed and Ezekiel lived for a number of years, retaining strong ties. Always aiming for novelty and authenticity (as least as he perceived it, and here vis-à-vis a precise reading of the Hebrew Bible), Ezekiel departed from the norms by conceiving an agonized, as yet unrepentant Eve without a navel.1

- 1In a letter to sculptor Edward Valentine, Ezekiel modestly points to Eve’s novelty: “It has at least the merit of originality among its many faults.” Letter from Moses Jacob Ezekiel to Edward Valentine, May 1, 1876, Valentine archives, Richmond, Virginia. John A. Phillips traces understandings of Eve’s story in western culture from biblical times to the present in his intellectual history, Eve: The History of an Idea (San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984).

Ezekiel briefly referred in his memoir to the moment he chose to depict, “When she hears the voice of God in the garden and is ashamed,” a description that closely resembles the work’s title: Eve Hearing the Voice.1 Accordingly, Ezekiel did not name his bronze with a standard, identificatory title as did nineteenth-century American contemporaries: the aforesaid Powers’s Eve Tempted and Eve Disconsolate, and Edward Sheffield Bartholomew’s Eve Repentant (1858-59, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford).2 Nineteenth-century Europeans also employed terse, broad titles; for instance, Eugène Delaplanche’s Eve After the Fall (1869, Musée d’Orsay) and Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux’s Eve Tempted (1871, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes), both stemming from France and carved in marble. Ezekiel originally titled his sculpture Eve After the Fall, which represents a decidedly Christian theological understanding of the creation story that he purposefully changed.8 Instead he settled on a title that hewed to the biblical verse: “And they heard the voice of the LORD God walking in the garden toward the cool of day; and the man and his wife hid themselves from the presence of the LORD God amongst the trees of the garden” (Gen. 3:8; author’s italics).3

By choosing such a specific title, directly connecting the sculpture to its textual source, Ezekiel aimed to shape viewers’ experience of, and response to, the work. He narrowed down the interpretive possibilities to one exact moment. Eve is tempted over the course of several verses, and is fallen or disconsolate over a number more. But she only first hears the voice in a few words, experiencing that initial horror of God chastising her for her disobedience. Eve attempts to muffle what Ezekiel imagined as God’s thunderous reproach, her thick hair covering her right ear almost entirely and her left nearly pressed on her shoulder. Ezekiel’s conception of Eve calls attention to that very instance, and he ensured his intentions by picking a deliberate title. As John Fisher aptly observes: “When an artwork is titled, for better or for worse, a process of interpretation has inexorably begun.”4 Moreover, the title opened up a conversation to curious visitors, which allowed Ezekiel to explicate his sculpture, to offer a “lesson” in a very public space, his popular studio in the ancient Baths of Diocletian where artists, musicians, politicians, and tourists came to view his art.5 The large clay sketch for Eve, not cast until around 1904, remained on view in his atelier for decades, a constant stream of guests voicing their admiration. Ezekiel once wrote of “turn [ing] my statue of Eve for my visitors to see” during a concert by Franz Liszt in his studio.6 Ezekiel’s title is fundamental to the work in a way that a more generic title would not be. It provides a point of entry into the sculpture by steering viewers to the foundational words of the Bible (“And they heard the voice of the LORD God”) that served as Ezekiel’s springboard rather than broadly referencing Eve’s powerful but well-worn story.

- 1Ezekiel, Memoirs, 179.

- 2Powers labored over the names of his sculptures, indicating the importance of titling in the day. Before settling on Eve Tempted, he called the work Temptation of Eve and Eve Before the Fall. Eve Disconsolate was once more poetically titled Paradise Lost and the more standard Repentant Eve and Eve After the Fall. See Richard P. Wunder, Hiram Powers: Vermont Sculptor, 1805-1873, Life, vol. 1 (Newark: University of Delaware Press, 1991), 182, 305-306.

- 8Ezekiel, Memoirs, 179.

- 3https://www.mechon-mamre.org/p/pt/pt0103.htm. Accessed July 27, 2020.

- 4John Fisher, “Entitling,” Critical Inquiry 11, no. 2 (December 1984): 298.

- 5Ezekiel was so famous in his lifetime that guidebooks for tourists to Italy listed the address to his studio, Piazza delle Terme 118. See K. Baedeker, Italy: Handbook for Travelers: Central Italy and Rome, tenth revised edition (Leipzig: Karl Baedeker, 1890), 116. He often welcomed eminent Americans to his studio, including patriots Ulysses S. Grant, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Taft. Among European royalty, Ezekiel counted Queen Margherita of Italy, King Victor Emmanuel III, and Kaiser Wilhelm II, as friends and visitors.

- 6Ezekiel, Memoirs, 261.

Ezekiel crafted Eve early in his career, when he was particularly attracted to biblical matter and before he became famous across the western world for his portrait busts and large public monuments. As a boy in Richmond, Ezekiel first made work of a biblical nature, turning to those narratives that he knew best. He executed a large drawing in crayon titled The Revolt of the Children of Israel in the Desert and the Stoning of Moses (ca. 1857), one of only a few childhood works mentioned in his memoir. His earliest amateur efforts as a sculptor include Cain Receiving the Curse of the Almighty (ca. 1857) and Moses Receiving the Law on Mount Sinai (ca. 1857). Ezekiel’s submissions for a prize from the Royal Academy of Art in Berlin, where he studied for two years, were biblical in theme: an allegorical bas relief titled Israel (1873, lost; 1904 smaller replica, Skirball Museum, Cincinnati), which earned him the award, and Adam and Eve Finding the Body of Abel (ca. 1873, lost). Later he modeled several more biblical works, including but not limited to a marble torso of Judith (ca. 1880, Cincinnati Art Museum), a lost bust of Esther (ca. 1890), and at least three sculptures of Jesus: a reclining Christ in the Tomb (1896) donated by a patron to the Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Consolation de Paris, built in remembrance of a fire that claimed the lives of 130-some people at an annual charity event; a bronze torso showing Jesus bowed with a heavy beard and pronounced crown of thorns (ca. 1886-89, Cincinnati Art Museum); and another bronze torso (after 1891, lost), mentioned in Ezekiel’s autobiography, made as a gift for Lady Sherbrooke, who placed it in her home in Surrey.1 Christ in the Tomb and the extant bronze torso also aimed for authenticity; Ezekiel presented Jesus with Semitic features.

Jewish holidays, traditions, and learning suffused Ezekiel’s life. His Orthodox grandfather petitioned the Virginia Military Institute, where Ezekiel trained as the school’s first Jewish cadet, to grant his grandson a furlough to come home for the High Holidays and Passover—unprecedented requests that were approved.2 In a letter to his mother from Berlin, the young sculptor writes of missing his family, particularly during the High Holidays.3 Even after his parents moved to Cincinnati and affiliated with Reform Judaism, Ezekiel remained observant. Living in Italy as a bachelor for over forty years, a much less auspicious environment to practice Judaism than with his family in Richmond or Cincinnati, the cities of his youth, Ezekiel kept the Sabbath and attended synagogue frequently.4 When news of his mother’s death reached him in Rome, Ezekiel sat shiva in his studio, and went to morning and evening minyan. In correspondence home to his father, Ezekiel wrote of studying the Zohar and Kabbalah, and Ezekiel goes out of his way to note in his memoir that his father owned all of Moses Maimonides’ writings. Other written material further demonstrates the sculptor’s command of Hebrew scripture.

Certainly there is nothing specifically Jewish about a lack of umbilicus, and over the ages rabbinical commentators did not weigh in on Eve’s navel. Rather, it is Ezekiel’s careful textual reading, lifelong fascination with the Holy Writ, and connection to Jewish tradition that set his sculpture apart from his non-Jewish predecessors. To be sure, Ezekiel’s enduring sympathy for his religiocultural heritage, and keen awareness of both the sacred book and Jewish thought, is demonstrated by some of his works’ iconography, including Eve without her bellybutton.

Ezekiel’s sculpture of Eve was greatly appreciated in its own day. In 1904, Eve Hearing the Voice was exhibited at the St. Louis World’s Fair, where it won the Silver Medal. A smaller replica in marble was ordered in 1884 by John J. Harjes (partner of J. Pierpont Morgan), who gifted the piece to Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany in 1902.5 Soon after, the Emperor placed the piece in the Bildergalerie (Picture Gallery) in Potsdam, a building near the Sanssouci Palace in Sanssouci Park.6 A different patron, a banker named M. M. Lowenstein, also purchased a marble Eve.7 Cast in gilded bronze, a small statuette of Eve was modeled at some point; this may be an Eve that Ezekiel gifted to his friend, physicist Alfonso Sella, on the occasion of his marriage.8 Ezekiel, and his sculpture of Eve, were so venerated that American novelist Mary Agnes Tincker based a character on him in her book, The Jewel in the Lotus (1884). That fictional sculptor worked in the ancient Roman thermae and was laboring on sculptures of Judith and “a large pallid Eve [who] shrank away from the curse, one perfect hand pushed out.”9 Dutch author Carel Vosmaer also based a character in his novel The Amazon (1881; English edition 1884) on Ezekiel. The artist in that story similarly lived in the Baths of Diocletian and was hard at work on a sculpture of Eve “crouching on the ground in shame, and huddling herself together as if to hide her figure, her one hand seeming to ward off Adonai, who has come to demand an account of her deed.”10 Vosmaer, like Tickner a non-Jew, almost surely learned the word “Adonai,” one of the Hebrew words for God, from Ezekiel during his visit to the artist’s studio. Yet again, Ezekiel demonstrates his Jewish perspective—and unabashed revealing of it in Catholic Rome—as well as his knowledge of the Hebrew Bible, in which God is referred to over four hundred times as “Adonai.”

Ezekiel’s oeuvre mostly comprises large-scale monuments, portraits, and biblical works, many noted here. Eve Hearing the Voice deserves special attention as much for its one-time celebrity as for the fact that it is, by all accounts, the first known sculpture of Eve by a Jewish artist, and in both iconography and name significantly deviates from the standard produced by Christian artists.

- 1Ezekiel, Memoirs, 298.

- 2Letter from Moses A. Waterman to VMI Superintendent Francis H. Smith, August 21, 1862. Moses Jacob Ezekiel papers, MS-0010, Virginia Military Institute archives, Preston Library, Lexington, Virginia. Letter from Moses A. Waterman to VMI superintendent Francis H. Smith, April 10, 1864, in ibid.

- 3Letter from Moses Jacob Ezekiel to Catherine Ezekiel, August 27, 1869, reprinted in Ezekiel, Memoirs, 456.

- 4Letter from Virginia DiBosis Vacca to Zebulon Hooker, February 10, 1950. Moses Jacob Ezekiel papers, MS #44, box 1, folder 6, American Jewish Archives, Cincinnati, Ohio.

- 5Catalogue of Mr. Henry C. Ezekiel’s Private Collection of Sculptures and Pictures (Cincinnati: Traxel Art Company, 1930), 13; “Art Notes,” New York Times (April 19, 1903): 8.

- 6Author, personal conversation with Silke Kiesant, Ph.D., Curator, Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation, Berlin-Brandenburg, February 9, 2021. In 1929, the marble Eve was moved to a theater in Potsdam, which was destroyed in the last days of World War II, along with everything in it. The marble was a little less than four feet tall, in comparison to the bronze at four and a half feet.

- 7“Sir Moses Ezekiel,” Cincinnati Enquirer (November 30, 1913): B8.

- 8Small statuette mentioned in Catalogue of Mr. Henry C. Ezekiel’s Private Collection, 13. Gift to Sella discussed in Ezekiel, Memoirs, 419.

- 9Mary Agnes Tincker, The Jewel in the Lotos (London: W. H. Allen and Company, 1884), 216.

- 10Carl Vosmaer, The Amazon (New York: William S. Gottsberger, 1884), 69.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2021.2

1. Samantha Baskind, "Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Eve Hearing the Voice," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2021.2.

Baskind, Samantha. "Moses Jacob Ezekiel, Eve Hearing the Voice." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), doi:1 0.22332/mav.obj.2021.2.