Jonathan Homrighausen, a doctoral candidate in Hebrew Bible at Duke University, teaches in Judaic Studies at the College of William & Mary. His research explores the intersection of Hebrew Bible, calligraphic art, and scribal craft. He is the author of Planting Letters and Weaving Lines: Calligraphy, The Song of Songs, and The Saint John’s Bible (Liturgical, forthcoming) as well as articles in Religion and the Arts, Image, Teaching Theology and Religion, Transpositions, and Visual Commentary on Scripture.

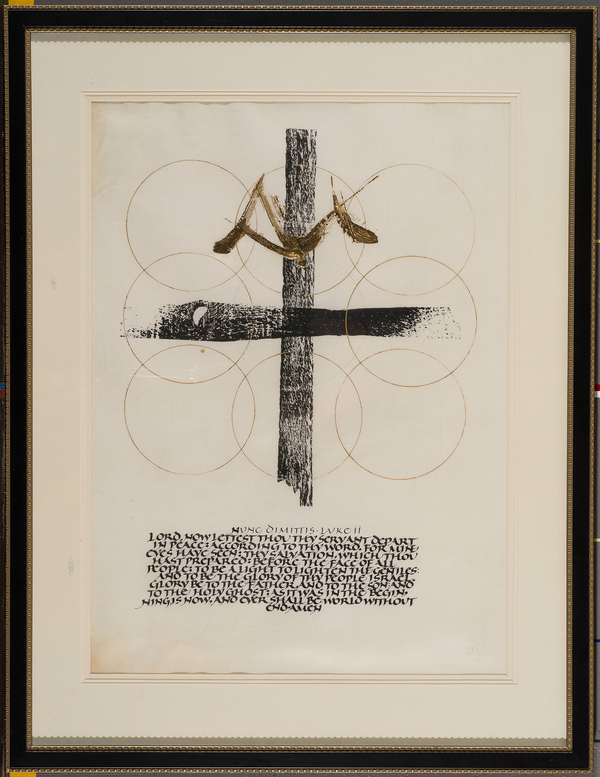

Bold, risky, and brash seem like unlikely tributes for a calligrapher’s work. The practice often evokes repetitive scribing of wedding invites, craftspeople rather than artists creatively playing with their texts. British calligrapher Donald Jackson’s The Black Cross invites you to look again.1 When it appeared in 1984, the British calligraphy and lettering arts scene was opening up to more expressive forms of text art alongside traditional lettering tasks. Today this piece resides at Saint Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral in Minneapolis, where it hangs prominently in the parlor. Looking back in 2021, Jackson described this piece as one of the most meaningful works of his career.2 It illustrates some of the ways contemporary calligraphic art engages sacred writ: through the interplay of word and image, recording the artist’s physical gestures, and making visible the divine.

The Black Cross began with a commission to create a piece based on the Nunc Dimittis (“Now, Lord, you may dismiss your servant”), Simeon’s canticle in the Gospel of Luke (2:29-32), traditionally prayed by monks during their day’s end Compline service. Jackson employs the translation in the 1662 Anglican Book of Common Prayer, with the Gloria added:

Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace : according to thy word.

For mine eyes have seen : thy salvation;

Which thou hast prepared : before the face of all people;

To be a light to lighten the Gentiles : and to be the glory of thy people Israel.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son : and to the Holy Ghost;

as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be : world without end. Amen.3

Jackson includes the prayer book’s verse breaks for chanting. This cues the viewer to think of the Lucan text along with its intended liturgical and musical performance during bedtime prayer, an hour evocative of death.4 The elderly Simeon had been promised that he would see the Messiah before his death. When he beheld the Christ Child in the Temple in Jerusalem, he sang this prophetic canticle and willingly surrendered his life. Jackson’s black cross imagery responds to these hallowed words.

- 1The Black Cross was commissioned for, and first published in Michael Taylor, ed., Contemporary British Lettering: A Collection of Newly Commissioned Work (London: Michael Taylor Rare Books, 1984). The artist has discussed it in Donald Jackson, Painting with Words: The Calligraphy of Donald Jackson (St. Paul, MN: The Minneapolis Institute of Arts, 1988), cat. no. 20; Donald Jackson, “Earning and Luck” (lecture, The Society for Calligraphy, September 4, 2021), hhttp://hdl.handle.net/10079/6438e7bd-f432-4b25-800c-4dca1b5bcc87. Jackson himself has shifted in how he refers to this piece. In his 1988 retrospective Painting with Words, he called it Nunc Dimittis and Gloria (emphasizing the text); in the 2021 lecture, he referred to it as The Black Cross (emphasizing the image).

- 2Jackson, “Earning and Luck.”

- 3The Church of England, “Nunc dimittis,” Common Worship: Services and Prayers for the Church of England, 2000, https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-re….

- 4Leonel L. Mitchell and Ruth A. Meyers, Praying Shapes Believing: A Theological Commentary on the Book of Common Prayer, rev. ed., Weil Series in Liturgics (New York: Seabury Books, 2016), 59.

Words and Wood: Word and Image

Calligraphic art often plays with word and image—indeed, for the lettering artist, words are images. Jackson writes these Gospel lines in closely packed capital letters in a script he describes as “Uncialish,” evoking the wide, round capital letters most associated with early medieval Latin Bibles. I often suggest contemplating calligraphy upside down so the viewer can consider the visual texture of the letterforms without being distracted by reading them. Jackson weaves these words together in a dense block leaving little space between lines and characters. This imposes a kind of visual volume for a liturgical proclamation in the present tense. Jackson’s letters convey Simeon’s joy at seeing his life’s end fulfilled.

Those black and triumphant letters, present-tense affirmations, contrast with the shadowy cross. Jackson tells the story of how he made The Black Cross: he had created the lettering but put off completing the artwork.1 On the day the piece was due to the client, he walked into his yard, chopped a few fragments off a spare apple box, brought them to the studio, inked them, and pressed them onto the page, fading away at left and right. It strongly resembles the evanescent marks traced on the foreheads of the faithful on Ash Wednesday. This cross is crude and rectilinear compared to the elegant, rounded letterforms beneath.

Jackson’s choice of cheap, rough wood suggests the coarseness of death by crucifixion. Unlike the elegant, fine-grained wooden crosses in churches around the globe, the wood of the actual cross was not meant to display beauty. It was a torture device for a public spectacle of state power. It was utilitarian and discardable, like Jackson’s apple box. The artist captures that brutal sentence more evocatively by using actual wood than if he had used a brush to paint a simulacrum of wood.

Just as medieval illuminated manuscripts generate interplays of word and image, so Jackson’s work sparks a conversation between cross and the nunc dimittis. After his joyful prayer, Simeon turns to Mary and warns her that her son is “a sign that will be opposed” (2:34), that “a sword will piece your own soul too” (2:35). Even this early in Luke, even when Jesus is a mere baby, his torturous execution looms ahead. Later Christian exegetes such as John of Damascus and Bonaventure would link Simeon’s words more explicitly to the passion.2 The shadowy cross visually foreshadows death.

- 1Jackson, “Earning and Luck.”

- 2Arthur A. Just, ed., Luke, Ancient Christian Commentary on Scripture: New Testament 3 (Downers Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 20), 50–51; Bonaventure, Commentary of the Gospel of Luke: Chapters 1-8, ed. Robert J. Karris, Works of St. Bonaventure 8, part 1 (St. Bonaventure, NY: Franciscan Institute Publications, 2001), 188–89.

Creation and the Body: The Artist’s Gestures

When Jackson stamped the wood against the vellum, he had already penned the letters and there was no time for a do-over. He took a gamble. This piece’s intuitive process, its risky execution, make its meaning as much as the visuals. Jackson echoes Simeon’s own tension: the tension between the “peace and light” of the canticle and the “sword and suffering” of the warning to Mary.1 Jackson’s tension lies between the slow, careful quill strokes and the quick, bold placement of wood on vellum.

When speaking about calligraphy as an artform, Jackson often invites his audience to look at the writing and mentally follow in the movements of the scribe. The viewer can perceive a scribe who writes slowly, with caution and care for how he knits the letters and words together. He writes with intention. He is completely focused, like Simeon who is wholly devoted to “the consolation of Israel” (2:25). Upon holding the child, Simeon proclaims peace and light. He can now die consoled. Though the text does not name his age, Christian tradition often imagines him as an old man.2

After the careful lettering, Jackson chopped wood and laid its shards on his page, drawing inspiration from the seventeenth-century Japanese sculptor Enku who carved 120,000 wooden statues of the Buddha with confident, spontaneous cuts.3 As Jackson explained how he made this cross: “It just came . . . I felt that I just had a baby.”4 Jackson’s metaphor echoes Mary, mother of Jesus, who in Luke 1 quickly accepts Gabriel’s call even as events in Luke 2 underscore the risk and anguish of her fate. Here the violence of chopping wood recalls other forms of death required for this art, not least the calf upon whose skin this piece was written.5 The process of creation echoes the text: Jackson snaps wood and plops it on the page. Enku carves his Buddhas with knife strokes. Likewise, a sword will pierce the heart of Mary because of this child (2:35).

Jackson made this work at a time when Western calligraphers increasingly turned to East Asian styles, drawing inspiration from their counterparts’ emphasis on gesture, line, and movement.6 Kazuaki Tanahashi, a Japanese Zen teacher and calligrapher who came to the United States in the 1970s, played a key role. Tanahashi taught alongside Jackson at a major conference in 1984, and Jackson later wrote a glowing cover blurb for Tanahashi’s 1990 work Brush Mind which introduced Zen calligraphy to many Western scribes.7 Jackson may have encountered Enku’s work through Tanahashi’s 1982 book about the sculptor.8 The flow of calligraphic inspiration from East to West has grown immensely since 1984; The Black Cross marks an earlier point in that story. From Tanahashi and Enku, Jackson may have gained a deepened appreciation of movement, intuition, and risk.

Like the pianist who spends months preparing for a concert only to find unplanned creative touches happening on the scheduled day, the calligrapher performs and improvises on the page with body, rhythm, and breath. As Jackson said of this piece and companion works when they were exhibited in 1988, “Our hearts as well as our minds are involved in our response to letters and their arrangement.”15

- 1François Bovon, Luke 1: A Commentary on the Gospel of Luke 1:1-9:50, ed. Helmut Koester, trans. Christine M. Thomas, Hermeneia (Minneapolis: Fortress, 2002), 104.

- 2Bonaventure, Commentary of the Gospel of Luke, 193.

- 3Jackson, Painting with Words.

- 4Jackson, “Earning and Luck.”

- 5Jonathan Homrighausen, Planting Letters and Weaving Lines: Calligraphy, The Song of Songs, and The Saint John’s Bible (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2022), 121–28.

- 6Nicolette Gray, Lettering as Drawing (New York: Taplinger, 1982), 1–2; William Gunderson and Charles Lehman, The Calligraphy of Lloyd J. Reynolds, 2nd ed. (Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society Press, 1989); Ewan Clayton, The Calligraphy of the Heart (Brighton, UK: self-published, 1996).

- 7Kazuaki Tanahashi, Brush Mind (Berkeley: Parallax Press, 1990).

- 8Kazuaki Tanahashi, Enku, Sculptor of a Hundred Thousand Buddhas (Boulder, CO: Shambhala, 1982).

- 15Jackson, Painting with Words.

Gold and Light: Seeing the Divine

After laying down the cross, Jackson created the golden circles and brush strokes around it. He calls these strokes “angels’ wings.” He crafted these wings by painting gesso (the binding agent which anchors gold leaf to vellum) with a coarse brush. Jackson’s use of gilding to depict angelic figures is a hallmark of his style, dating back at least as early as his 1976 Fear God and Give Glory to Him; many more appear in The Saint John’s Bible.1 By gilding the shape of an angel, Jackson both reveals and conceals their presence: the gold shines loudly on the page, but avoids anthropomorphic depictions of divine beings which can easily slide into kitsch. Just as the careful black letters contrast with the bold black cruciform, the golden circles’ perfect geometry balances the chaotic angels’ wings.

As with the letters and the cross, the reader can imagine how Jackson moved his arm as he painted the gesso. Bonaventure goes so far as to say that Simeon was dancing for joy at sight of the Christ child.2 One can imagine the choreography of Jackson’s arm and brush, the upward flicks under the gold, the strokes which convey motion through their diagonal slants. As the viewer moves and light shines off these angels at different slants, the gilding appears to flicker like flame. The angels come to life.

Simeon proclaims he has seen God’s salvation; this piece visually presents redemption in the form of light. Simeon’s “light to lighten the Gentiles” draws on Jewish scriptures’ imagery of God as light, especially Isaiah: “Arise, shine; for your light has come” (60:1).3 Later in Luke, John the Baptist echoes Simeon when he declares that “all flesh shall see the salvation of God” (3:6). Biblically, seeing is believing; that which can be seen can also be a public sign “in the presence of all peoples” (Luke 2:31).4 For today’s Christian who cannot literally hold the infant Jesus like Simeon did or baptize him like John did, the gold in this composition makes shifting light visible in ways that inert ink and pigment do not.

The Black Cross has shone forth since its 1984 creation. Fourteen years later Jackson would commit to his career-defining commission, The Saint John’s Bible, an illuminated manuscript of the whole Catholic canon created under the direction of the Benedictine monks of Saint John’s Abbey in Minnesota, completed in 2011.5 The Black Cross presages the visual tropes of the massive Bible, especially Jackson’s use of gold and tendency toward abstraction. Further, the piece now lives in a cathedral, a liturgical space rather than an art museum. Parishioners sit near it as they meet and consult, and perhaps pause to read its words. People walk by it and see its gold from different angles. The Black Cross continues to make its light visible.6

- 1Jonathan Homrighausen, “Words Made Flesh: Incarnational, Multisensory Exegesis in Donald Jackson’s Biblical Art,” Religion and the Arts 23 (2019): 240–72, https://doi.org/10.1163/15685292-02303003.

- 2William Hyland, “Why Is Simeon Dancing? The Unity of Exegesis, Theology and Devotion in the Work of Bonaventure,” Spiritus: A Journal of Christian Spirituality 19, no. 2 (2019): 271, 278, https://doi.org/10.1353/scs.2019.0031.

- 3See also Isaiah 60:19, 42:6-7, 49:6, 49:8-9, 51:4-5. Bovon, Luke 1, 102–3; John T. Carroll, Luke, New Testament Library (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2012), 78. On the metaphor of God as light more generally in the Hebrew Bible, see William P. Brown, Seeing the Psalms: A Theology of Metaphor (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2002), 81–104, 197–99.

- 4Brittany E. Wilson, The Embodied God: Seeing the Divine in Luke-Acts and the Early Church (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021), 201, 205–6; Yael Avrahami, The Senses of Scripture: Sensory Perception in the Hebrew Bible, LHBOTS 545 (New York: T&T Clark, 2012), 225–32.

- 5On The Saint John’s Bible, see Christopher Calderhead, Illuminating the Word: The Making of The Saint John’s Bible, 2nd ed. (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 2015).

- 6I would like to thank George Greenia and Christopher Redmon for their comments on a draft of this article. I am also indebted to Mitch Rossow and to Linda Schelin of Saint Mark’s Episcopal Cathedral, Minneapolis, for arranging for me to have print-quality images of the piece.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.7

1. Jonathan Homrighausen, "The Black Cross," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.7.

Homrighausen, Jonathan. "The Black Cross." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.7.