Utah artist George Martin Ottinger painted Aztec Maiden during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, when numerous theories proliferated about the history and origins of indigenous American civilizations. French antiquarian Charles Brasseur de Bourbourg, for instance, drew extensive parallels between Maya and Egyptian religious beliefs and proposed the lost continent of Atlantis as a common cultural source, whereas Désiré Charnay, a French émigré working under American patronage, posited a migration theory that traced Toltec cultural origins to northern Europe. Ottinger, an aspiring history painter and local lecturer on pre-Columbian subjects, was familiar with these and other theories of cultural diffusion.1 Aztec Maiden participates in this cultural debate, signaling the artist’s adherence to then-current Latter-day Saint interpretations of indigenous ancestry. By portraying indigenous Mexicans wearing classicized garments and inhabiting an orderly, stage-like setting, Aztec Maiden advocated hemispheric Lamanite identification, or a belief that native populations throughout North and South America are blood-descendants of ancient Book of Mormon peoples. Ottinger’s imagery also reflects late-nineteenth-century LDS interest in Mexico as a region for colonial and spiritual expansion.

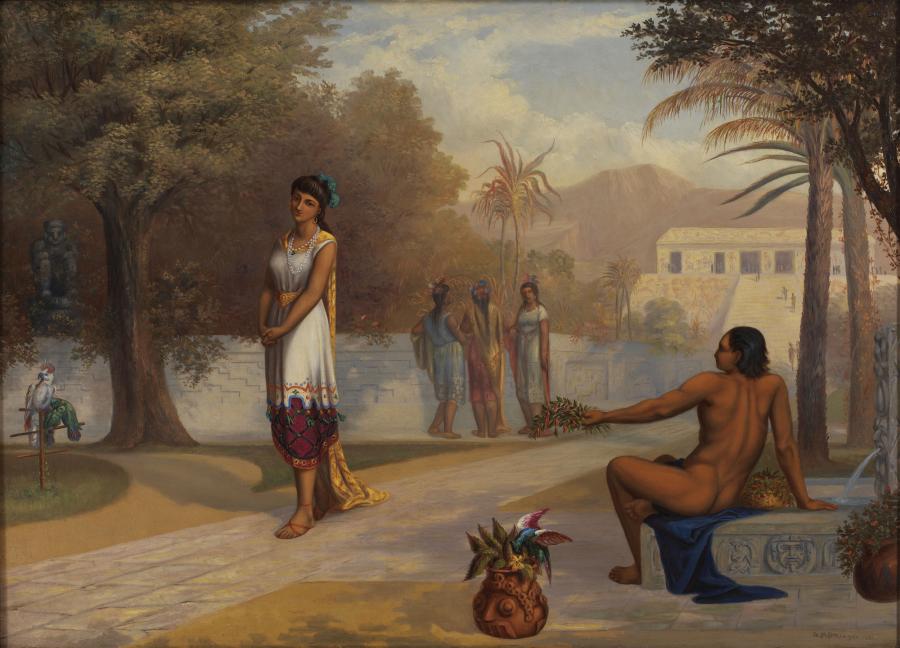

Aztec Maiden was one of nearly thirty “Old America” paintings that Ottinger produced between 1867 and 1892. The painting typifies the peaceful and idealized appearance of indigenous American cultures in these works. Walking down a stone path, the title figure demurely considers the flowers being offered to her by a young man. She wears a tunic-style dress reminiscent of Roman garb, and turquoise blossoms adorn her plaited hair. The young man rests on the ledge of a fountain with a basket of flowers beside him. Although nude, he exudes grace and refinement in a semi-reclined pose redolent of ancient Greek statuary. In the background three women gather beside a carved stone wall; the neatly manicured enclosure provides a serene and spacious setting for their afternoon leisure. Domesticated parrots, potted plants, mature shade trees, and sculptural works add to the ordered appearance of the garden, while a distant temple, luminous against lush tropical foliage and mountainous terrain, stands as further testament to the cultural sophistication and civic order of ancient Aztec people.

Ottinger’s idealized portrayal of an Aztec subject reflects the esteem that LDS church authorities accorded indigenous American civilizations at this time. From ca. 1830 throughout the nineteenth century, LDS Church leaders preached that indigenous Americans were descended from Israelites who had migrated to the Americas to escape the Babylonian conquest of Jerusalem. The task of LDS missionaries was to bring the gospel to American Indians and thereby restore their ancestral covenant with God. Once converted, Native Americans would assume a leading role in building a New Jerusalem in the Americas.2 Hemispheric Lamanite identification extended these ideas to include native populations throughout the Americas.3 Ottinger adhered initially to Apostle Orson Pratt’s hemispheric proposal of Book of Mormon geography, which encompassed the entirety of North and South America and gained quasi-official status when it was added as a footnote to the 1879 edition of the Book of Mormon.4 As historical knowledge about Mesoamerican traditions improved, he refined his geographical interpretation of Book of Mormon passages to focus exclusively on the pre-Hispanic cultural regions of Mexico and Central America.

Ottinger’s approximation of the Maya Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque, Mexico in Aztec Maiden opens the interpretative possibility that he intended this painting to depict a post-scriptural view of an ancient Book of Mormon city called Zarahemla. Like other exponents of hemispheric Lamanite identification, Ottinger pored over recent archaeological studies in an effort to coordinate scriptural descriptions of topographical features and architectural styles to known Mesoamerican sites.5 The conflation or even outright substitution of geographical labels and Mesoamerican site names for the Book of Mormon’s more vague terminology became common practice during this period. Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula began to replace “Land of the Bountiful” in unofficial LDS publications, while the Isthmus of Tehuantepec became synonymous with the Book of Mormon’s “Narrow Neck of Land.” Ottinger contributed to this verbal slippage when he posited a precise correlation between Zarahemla, an important city in the Book of Mormon, and Palenque, a Classic Maya city-state located in Chiapas, Mexico. Writing for the LDS periodical Juvenile Instructor, he speculated that “[t]hose remarkable and world-famous ruins known under the name Palenque may yet be proven to be the remains of that ‘great city and religious center’ of the [Book of Mormon] aboriginals, called Zarahemla."6

Visual affinities in Ottinger’s oeuvre, particularly among works representing Mesoamerican and Book of Mormon subject matter, attest to the religious resonance that paintings such as Aztec Maiden held for nineteenth-century LDS viewers. Among the first artists to paint historical episodes from the Book of Mormon, Ottinger had no artistic precedent to guide his visual renditions of LDS scripture. The resulting imagery is a cultural composite, blending ancient Maya architecture and other motifs from different Mesoamerican groups with Roman-style clothing to approximate biblical-era Israelite civilization in the Americas.7 Aztec Maiden employs a similar pictorial strategy to suggest cultural and genealogical continuity between ancient Israelites in the Book of Mormon and their descendants, the pre-Hispanic Aztec civilization identified in the painting’s title. As in Ottinger’s religious history paintings, the principle figures in Aztec Maiden wear Roman-style tunics and cloaks that signify their Old World heritage, while their surroundings contain Mesoamerican motifs and architectural signatures that locate the scene in the New World. In addition to the Maya-inspired temple, Aztec Maiden includes references to the so-called Aztec Calendar Stone on the base of the fountain, the Aztec deity Tlaloc on a clay flower pot, and a generalized Mesoamerican step-fret motif on the garden wall. Yet in spite of his extensive library on pre-Columbian topics, Ottinger incorporates these elements with little regard for their cultural meaning or historical context. He may have felt it unnecessary to distinguish between various Mesoamerican traditions since LDS doctrine teaches that all native populations share a common Israelite lineage.

Another impetus for this painting was the LDS Church’s proselytizing campaign south of the border. During this period, the LDS Church established colonial settlements in northern Mexico and dispatched missionaries to proselytize in and around Mexico City. Ottinger painted Aztec Maiden in 1881, the same year that Apostle Moses Thatcher dedicated Mexico for missionary work on behalf of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Held atop the sacred Aztec volcano Popocatépetl near Mexico City, Thatcher’s ceremony at once celebrated the successful baptism of enough members to organize a second Mexican branch of the LDS Church in Ozumba, a small community at the base of the volcano, and announced the church’s desire for further expansion through “the redemption of Lamanites in that land.”8 By depicting indigenous women modestly dressed and engaged in peaceful activities, Aztec Maiden highlights cultural traits that may indicate the presence of “believing blood,” a nineteenth-century phrase that referred to Latin Americans’ apparent receptivity to the tenets and mores of LDS faith.9

Aztec Maiden advocates the nineteenth-century theory of hemispheric Lamanite identification. In so doing, the painting inserts a distinctly LDS perspective in larger cultural debates about pre-Columbian cultural origins. It also helped to establish a religious iconography for paintings depicting Book of Mormon narratives and provided an intentionally positive image of Mesoamerican civilization during an era of LDS colonization and proselytization in Mexico. Yet while the painting emblematizes LDS belief in the esteemed heritage and providential destiny of indigenous Americans, there remains an undercurrent of primitivism. The fundamental premise of hemispheric Lamanite identification centers on the belief that native peoples had forsaken their ancestral covenant with God and fallen into cultural decay. Complicating matters further, the term “Lamanite” had acquired derogatory racial implications based on LDS settlers’ frontier conflicts with Utah tribes.10 While Ottinger foregrounds pre-Columbian architectural achievement and advanced social order in the painting, he also maintains potent symbols of wilderness – tropical parrots, thick foliage, male nudity, and dark skin – that reveal the then-current bifurcated perspective of indigenous Americans as both noble and savage, sacred and profane.

Notes

Notes

1. For a biography of George Martin Ottinger, see Heber G. Richards, “George M. Ottinger, Pioneer Artist of Utah,” Western Humanities Review 3 no. 3 (July 1949): 209-218; Richard G. Oman, “Outward Bound: A Painting of Religious Faith,” BYU Studies 37, no. 1 (1997-1998): 75-81; and Vern G. Swanson, Robert S. Olpin, and William C. Seifrit, Artists of Utah (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith Publisher, 1999), 185-189. Ottinger’s journal is preserved in the Western Americana Division, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

2. This narrative is drawn from the First and Second Books of Nephi in the Book of Mormon, as well as in Third Nephi, chapter 21. For greater analysis of these themes in LDS theology, see Armand L. Mauss, All Abraham’s Children: Changing Mormon Conceptions of Race and Lineage (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003).

3. When Joseph Smith, the founder of the LDS Church, and other early church leaders spoke about the need to reclaim the Lamanites, they typically referred to American Indians living in the United States and its Western territories. An expanded geographical approach grew in popularity in the middle decades of the nineteenth century and was well-established in LDS thinking by the time Ottinger joined the church in 1858. See John-Charles Duffy, “The Use of ‘Lamanite’ in Official LDS Discourse,” Journal of Mormon History (Winter 2008): 118-167; Thomas W. Murphy, “From Racist Stereotype to Ethnic Identity: Instrumental Uses of Mormon Racial Doctrine,” Ethnohistory 46, no. 3 (Summer 1999): 451-480; and Ronald R. Walker, “Seeking the ‘Remnant’: The Native American During the Joseph Smith Period,” Journal of Mormon History 19, no. 1 (Spring 1993): 1-31.

4. Orson Pratt, December 27, 1868 and February 11, 1872, Journal of Discourses (Liverpool and London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854-1886), 12:337-46; 14:323-35. The 1879 and 1911 editions of the Book of Mormon contain numerous geographical references that were removed in subsequent editions.

5. Probable identifications of Book of Mormon geography developed in tandem with Mesoamerican studies, which reached new heights in the nineteenth century. Against this backdrop, LDS adherents began looking to Mesoamerican archaeological evidence to corroborate the historical narrative told in the Book of Mormon. Elder Charles Blancher Thompson, for example, published Evidence in Proof of the Book of Mormon (1841) in an effort to provide an ecclesiastical framework for American explorer John Lloyd Stephens’ and English artist Frederick Catherwood’s bestselling travelogue, Incidents of Travel in Central America, Chiapas, and Yucatan (1840).

6. George Martin Ottinger, “Votan, the Culture Hero of the Mayas,” Juvenile Instructor (March 1, 1879): 58.

7. Noel A. Carmack, “‘A Picturesque and Dramatic History’: George Reynolds’s Story of the Book of Mormon,” BYU Studies 47, no. 2 (2008): 115-141.

8. Rey L. Pratt, Conference Report of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, April 1930 (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, semi-annual), 127. For more on LDS settlement in Mexico, see F. LaMond Tullis, Mormons in Mexico: The Dynamics of Faith and Culture (Logan: Utah State University Press, 1987).

9. The concept of “believing blood” also applied to LDS converts of European and Polynesian descent. See Mauss, All Abraham’s Children, 17-40.

10. On the development of LDS cultural relations and attitudes toward native populations in Utah, see Jared Farmer, On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008); Mauss, All Abraham’s Children, 58-68; and Nathan Rees, “C.C.A. Christensen, Joseph Preaching to the Indians,” Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), http://mavcor.yale.edu/conversations/object-narratives/c-c-christensen-joseph-preaching-indians

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.obj.2015.3

1. Breanne Robertson, "George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2015.3

Robertson, Breanne. "George Martin Ottinger, Aztec Maiden." Object Narrative. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015). doi:10.22332/con.obj.2015.3