Laura Levitt is Professor of Religion, Jewish Studies, and Gender at Temple University. She is the author of The Objects that Remain (2020); American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (2007); and Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home (1997) and a co-editor of Impossible Images: Contemporary Art After the Holocaust (2003) and Judaism Since Gender (1997). She is currently writing about the offerings left at The Tree of Life Synagogue and at George Floyd Square while working on a book about the former East German writer Christa Wolf. https://lauralevitt.org/

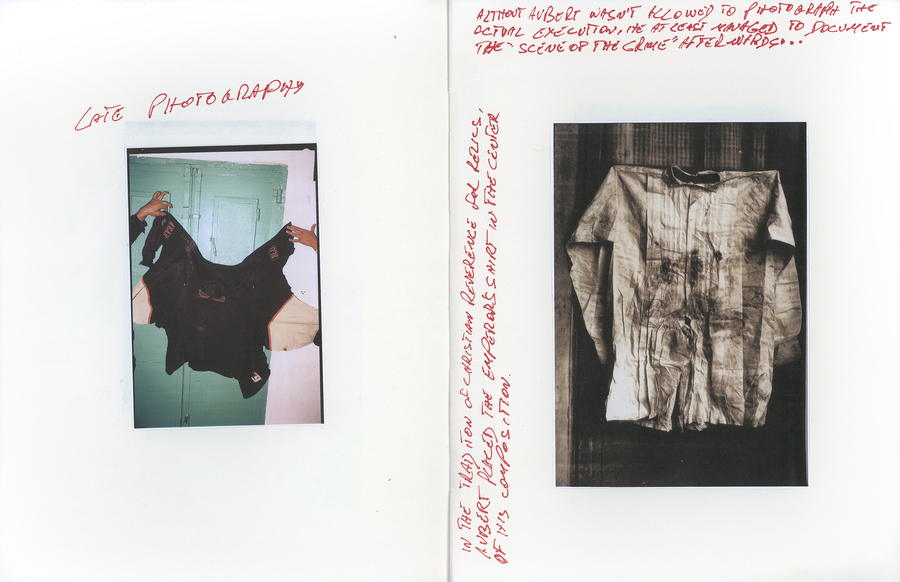

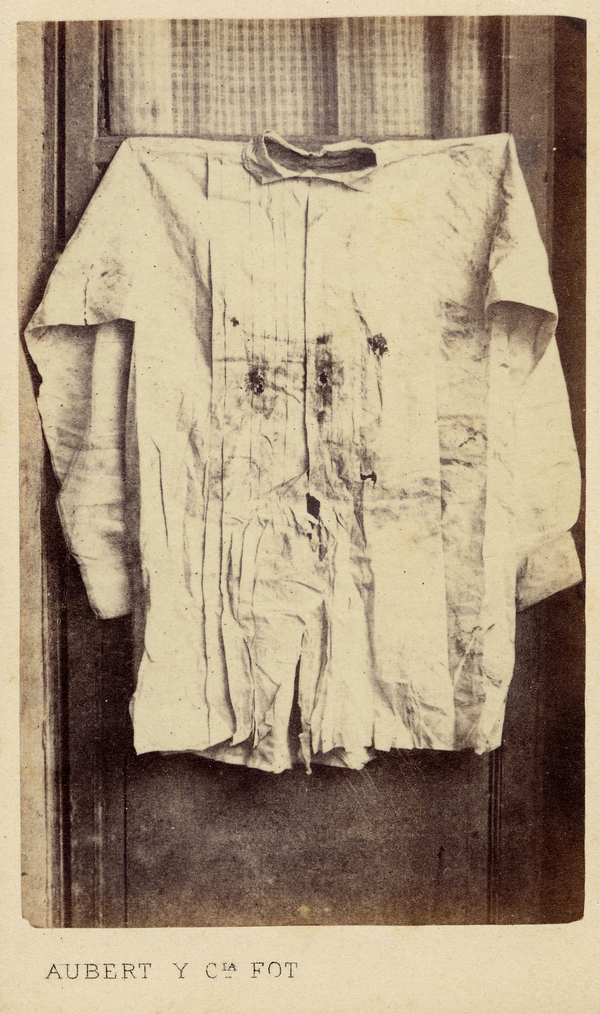

In her Object Narrative about François Aubert’s iconic Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt, Eleanor Laughlin describes vividly both its intimate and its wide-reaching allures (Fig. 2). As she explains, the carte-de-visite had political and commemorative powers “offering the living both visual and tactile connections to the deceased.”1 And, even as an object of mourning, it offered a broad international public access to this major political event. But even more than this she writes, it also “functioned in the Mexican religious context as a relic or object of reverence.”2 In The Resolution of the Suspect (Fig. 1), photographer Miki Kratsman builds on the reliquary nature and the transitive qualities of the carte-de-visite, creating a diptych: the historic image on one page of the centerfold and his own photograph of the bloody garment of a single unnamed Palestinian martyr on the other.3 Kratsman asks if a “Christian reverence for relics” might interrupt the pervasive indifference to Palestinian suffering in the present.4 He asks why it is so difficult to call attention to the violence that is contemporary Palestinian life and death under Israeli occupation. Not only does he build on the indexical nature of photography and its relation both to mourning and commemoration, Kratsman taps into the promise of contemporary photography as reliquary.

- 1Eleanor A. Laughlin, "Carte-de-visite Photograph of Maximilian von Habsburg’s Execution Shirt," Object Narrative, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016), doi:10.22332/con.obj.2016.1

- 2Ibid.

- 3Miki Kratsman and Ariella Azoulay, The Resolution of the Suspect (New Mexico: Radius Books/Peabody Museum Press, 2016).

- 4Ibid., 151.

As Laughlin explains, articles of clothing can absorb sacred presence, as in the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, transferred directly onto the cloak of Juan Diego, “saturating the cloth with the visible presence of the divine.”1 The carte-de-visite itself took on this reliquary function in remembrance of the executed emperor. The Resolution of the Suspect offers a range of haunting images about the horrors of Israeli occupation; as Kratsman’s collaborator and scholar of visual culture Ariella Azoulay explains in her introduction to Kratsman’s work, Kratsman’s photographs tell a terrible tale about “the drama of portrait-making in circumstances wherein certain people—an entire population of individuals—are doomed to appear under the resolution of the suspect.”2 Although Kratsman’s photographs include images of Palestinians marked for abuse and often death, the book centers on targeted subjects, shuhaded, martyrs whose stories can only be told, in some instances, through the soiled garments left behind.3

Kratsman’s diptych offers starkly contrasting images. The execution documented by the Aubert photograph was a major public event. It elicited responses from around the globe and resulted in significant consequences for the governance of Mexico. The photograph itself, as Laughlin points out, became part of this event and served as both a trophy and an object of mourning. By contrast, the Palestinians executed by Israelis often live and die in relative anonymity, commemorated only by their families and their communities through martyr posters.4 The global attitude towards Israeli aggression against Palestinians is largely one of apathy, and Palestinians themselves are disillusioned by the failure of so many images of suffering to garner international empathy, much less bring about change. Where Maximilian was a famous colonial emperor, the Palestinian referred to in Kratsman’s photograph, like all of those depicted in his book, are unknown, powerless over the fate of their lives and their homes.5

Kratsman’s color print appears at the center of the left side of the two-page spread. It depicts a level of violence that the carte-de-visite does not. The historical shirt is hung neatly, stoically, in sepia tones against a simple backdrop; the contemporary garment is distended, the fabric pulled in opposite directions. The quiet solemnity of the carte-de-visite contrasts with the too-bright flash in the Kratsman photo. The angle of the composition is awry as if done in a hurry.6

Kratsman carefully placed the two photographs together within the pages of his sketchbook, and then added his English annotations in bright red marker, re-photographing the open double-page spread. He barely annotated his own photograph. Just above it he wrote in capital letters “Late Photography,” a reference to the concept of the “late photograph,” an idea developed over the past decades to describe photographs taken in the aftermath of tragic events, which furnish evidence of violence, but offer minimal commentary.7 Here too there is no commentary. Even Azoulay neglects to mention this diptych in her introduction. Instead, this late photograph simply suggests the fate of all the other Palestinians depicted in this book.

The carte-de-visite occupies the opposite page, carefully reproduced. Its sepia tones echo the aging blood that stained Maximilian’s once-white shirt a rusty brown. These colors contrast sharply with both the contemporary photograph and Kratsman’s fresh red annotations. This text runs not only above the image of Maximilian’s shirt but also along its side, disturbing what is otherwise a more formal composition. In capital letters, Kratsman wrote, “Although Aubert wasn’t allowed to photograph the actual execution, he at least managed to document the 'scene of the crime’ afterwards . . .”8 An additional text runs down the inside seam of the page. To read this text one must turn the book ninety degrees or twist one’s head to see the words clearly. There, in the same shaky handwriting, Kratsman wrote, “In the tradition of Christian reverence for relics, Aubert placed the Emperor’s shirt in the center of his composition.”9 And Kratsman, echoing Aubert, placed this diptych in the center of his book.

Although the notion of the contact relic articulated by Laughlin originates in a Christian legacy of the reverence for objects and their representation, the allure of relics is much more pervasive.10 Part of what made the carte-de-visite of Maximilian’s shirt so powerful was an abiding sense of the sacred nature of both clothing and its representation as holders of vital matter. In the case of the carte-de-visite, the “portrait-like representation of the shirt” itself suggests, as Laughlin makes clear, “a transfer of power from the actual shirt to its image.” Kratsman’s overt invocation of this reverence brings the late photograph into contact with this legacy.

Describing Aubert’s nineteenth-century photograph, art historian Graham Smith writes, “Pinned to the crossbeam of a window, the shirt is presented like the target it was, and forms a bleak, artless image whose main purpose seems to be to inventory the bullet holes.”11 And yet, it is much more than this. Smith himself draws connections between the carte-de-visite photograph and not only the Emperor’s own self-fashioning as a martyr but the Christian iconography of the photographer. Smith shows how Aubert’s image draws on seventeenth-century Spanish artist Francisco de Zurbarán’s famous depictions of saints. In reference to one of these paintings, The Martyrdom of Saint Serapion, Smith writes, “Because Serapion’s head and hands are almost completely hidden in shadow, the habit becomes a surrogate for the saint and represents his martyrdom in much the same way that Maximilian’s shirt signifies the emperor’s execution” (Fig. 3).

- 1Laughlin, "Carte-de-visite Photograph.”

- 2Kratsman and Azoulay, The Resolution, 25.

- 3As he began work on this project in 2011, Kratsman explained that he wanted to “explore how Palestinians appear to the eye of the beholder, whether that person is a passerby, a newspaper reader, or an Israeli soldier.” He planned to include a cluster of different photographic interventions. Images of “Palestinians as targets, shot with a lens used by Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) unmanned aerial vehicles,” isolated “images of those identified as shahids or martyrs as portrayed on neighborhood posters or placards,” as well as images made in the spirit of “Francois Aubert's photograph of the shirt of Maximilian, ruler of Mexico, just after his execution in 1867” featuring “the last piece of clothing worn by a Palestinian before he was killed.” And finally, the book was to include what became a field study on Facebook where Kratsman revisited many of the photographs he has made over the past 33 years of Palestinians under Israeli occupation. This project would ask “Palestinians to mark his photos to indicate who is ‘wanted,’ a victim, or a shahid,” identifying those captured in the background of some of those photographs. perma.cc/4GLK-SV4L. It should also be noted that in this description the website uses the English form of the plural of “shahid” and not the Arabic “shuhadeh,” I thank one of my anonymous external readers for pointing out this error.

- 4On these posters, see Laleh Khalili, Heroes and Martyrs of Palestine: The Politics of National Commemoration (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), doi:10.1017/cbo9780511492235

- 5I thank one of the anonymous readers of an earlier version of this essay for the eloquent phrasing of this assessment.

- 6I again thank one of the anonymous readers for this important assessment.

- 7Kratsman and Azoulay, The Resolution, 150. On late photographs, see Simon Faulkner, “Late photography, military landscapes, and the politics of memory,” Open Arts Journal, no. 3 (2014), doi:10.5456/issn.2050-3679/2014s22sf Faulker writes that late photographs "are photographs that picture material remains left in the aftermath of events that often involve forms of violence. These photographs are usually high in detail, but formally simple, framing aftermath sites in ways that suggest the reservation of judgment and commentary upon the things they picture.” See also, David Campany, “Safety in Numbness: Some remarks on the problems of ‘Late Photography,’” in Where is the Photograph? ed. David Green (Photoworks/Photoforum, 2003). Online at: perma.cc/LS7B-C5XJ

- 8Kratsman and Azoulay, The Resolution, 151.

- 9Ibid.

- 10On the notion of the contact relic see Scott Montgomery, “Contact Relics,” in Encyclopedia of Medieval Pilgrimages (2012) doi:10.1163/2213-2139_emp_SIM_00235 As Montgomery describes, the term “contact relic” can describe, “two entirely different classes of relics”: secondary and/or tertiary relics. Montgomery writes, “Secondary relics are items that came into contact with a saint during his or her lifetime, such as the tunic of Francis Assisi. Tertiary relics are items that have come into contact with relics and thereby absorbed some of their power, becoming another form of contact relic, such as the strips of cloth (brandea) that were touched to the tombs of saints.” As Montgomery explains, this touching allows the power of the holy to spread.

- 11Graham Smith, “Francois Aubert’s Shirt of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico,” History of Photography 16, no. 2 (1992), doi:10.1080/03087298.1992.10442542, 172. I am also reminded of Pasolini’s bloody shirt. See Ara H. Merjian, “The Shroud of Bologna: Lighting Up Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Sensational Corpus,” in Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practices, ed. Sally M. Promey (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 447-458.

Kratsman’s explicit invocation of this Christian tradition serves as a connective tissue between the two portions of the diptych and his broader project. Together these conflicting images, an aging relic of an Emperor and the portrait of the jacket of a contemporary Palestinian shahid, ask us to reconsider this “reverence for relics.” What might it mean, Kratsman asks, to see this work in light of the Christian tradition of veneration that Laughlin and Smith each describe? By giving new life and new urgency to this legacy, Kratsman attempts to speak to a contemporary global audience about violence, vulnerability, and political power. His recirculation of the carte-de-visite challenges us to ask who gets to be a martyr and what a contemporary martyr looks like.

The author wishes to thank Emily Floyd for her deft editorial work on this essay. She is also grateful to Ruth Ost and the two anonymous readers for their suggestions and critical engagement.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2018.2

1. Laura S. Levitt, “Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect,” Object Narrative, in MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018), doi:10.22332/mav.obj.2018.2

Levitt, Laura S. “Miki Kratsman, Diptych from The Resolution of the Suspect.” Object Narrative. In MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018), doi:10.22332/mav.obj.2018.2