Olaya Sanfuentes is a tenured history professor at the Pontificia Universidad Católica, Chile. She received her PhD in Art History from the Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona and her MA, from Georgetown University, USA. She teaches courses on sixteenth-century Latin America, Public History, and Critical Heritage Studies, as well as seminars on visual and material culture studies. She has written books, chapters of books, and articles in peer-review journals in addition to narratives for museums and videos. She has also written history books for children.

You know, I’m no patriot, but I love my fellow countrymen. A whole land, a Fatherland, is something abstract. But someone from the same part of the world is something concrete.

Joseph Roth, The Emperor’s Tomb

To some degree, nativity scenes are representations in miniature of a society at a given moment. Embracing the belief that the humblest of individuals participated in Jesus’s birth with their presence and their gifts alongside the wisest, Christians of every era have wished to display their own participation and contribution to this foundational Christian event. This article describes the ways in which a traditional, rural-inspired society like that of Santiago, Chile at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth centuries expressed itself through its nativity scenes.1 Foreigners passing through Chile left visual and literary records which also shed light on its population. The population of Santiago in the 1800s was characterized by its rural mentality and for the inclusiveness and shared experience of its celebrations in public space, reaching across different levels of society.

- 1The rurality in question is settled both in Santiago’s nineteenth-century mentality and imaginary. I am not quantifying rurality, nor contrasting urban versus rural, but referring to the countryside as an important character in cultural representations of the epoch. Despite the fact of an increasing urbanization process, poor families used to have orchards and rich families had huge estates. All depended on agricultural production. But most important for this paper, the religious experience was inspired by nature.

The origins of the nativity scene

The nativity or manger scene is a three-dimensional representation of Jesus’s birth in Bethlehem in a barn or, more precisely, in a manger. In the early days of Christianity, before Christianity was a majority religion, and in times of heresy and other obstacles for the Church, Christ’s mighty and victorious characteristics were emphasized to encourage belief. Over time, Christianity became a dominant religion, and the Church was seen as a distant institution so new strategies had to be found to make people feel a personal connection to Christ and the Church. In the thirteenth century, St. Francis of Assisi had a special fondness for the topic of the Incarnation of Christ, which was difficult to explain with words. He sought to promote devotion through emotional elements to help people experience this critical event for Christianity.1 Inspired by this interest, St. Francis revealed aspects of Christ that went beyond the victorious and powerful. St. Francis, as well as his contemporary, St. Bernard, focused on Christ the child, emphasizing his humanity and humility, someone who the gospels describe as worshiped by shepherds and the poor. This late medieval shift in Christocentric devotion invited the faithful of all walks of life to participate in the commemoration of Jesus’s birth. St. Francis pioneered the ritual of reenacting the events of Christ’s birth as a devotional practice in towns. Live presentations of the nativity allowed those who could not read to celebrate and learn. Actors, accompanied by shepherds and their animals, brought Jesus, Mary, and Joseph to life in nativity scenes enacting affectionate, popular celebrations of Jesus’s birth.

St. Francis’s teachings quickly spread throughout Europe and were brought to Latin America via the Spanish conquest and evangelization. Depictions of Christ’s birth also emerged in the visual arts, particularly painting and sculpture. Artists represented the Christ child as a typical newborn baby: naked, a symbol of his humanity. His humble nature was also asserted by the place chosen to shelter the Holy Family and the animals—an ox and a donkey—which accompanied him. At the same time, artists painted Christ as resplendently white or emanating light to suggest his divine nature. For contemporary viewers, the white color of the Christ child’s skin did not indicate a specific racial identity, but rather referred to his inner light, which transcended race. This representation derives from the Apocryphal Gospel of James, which describes Jesus as projecting a bright light at his birth, a light that emerged from and shone around the child himself. Medieval paintings of the nativity represented Christ as a divine being while also human, consecrating realism as a form of worship.2

The gospels and apocryphal accounts offer evocative descriptions of the other actors who shared nativity scenes alongside the Holy Family. Although the canonical gospels (Luke and Matthew) describe only the three main figures (Mary, Joseph, and Jesus), the shepherds, and wise men, the apocryphal narratives also include cows and donkeys, and characterize these animals differently. The apocryphal gospels describe the scenery and the climate of the scene as well: the Protoevangelium of James as well as the Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew, for example, offer information about the cave, the manger, and the light that surrounded Jesus at his birth.3 Many artists produced engravings, paintings and sculptures inspired by this description, such as the images by Theodor Galle (1566-1638). Galle produced many engravings which then migrated to Spanish America, inspiring local artists. In his Adoration of the Shepherds, a brilliant and eloquent light emanates from the newborn baby Jesus. The Protoevangelium of James also gives information on the nativity of Mary. Large nativity scenes frequently incorporate the birth of the Virgin to her parents, Anna and Joachim. Additionally, this gospel relays that Jesus was born in a manger of oxen, wrapped in swaddling clothes, and that he was born just before the Massacre of Innocents.

- 1Bonaventure, The Soul’s Journey into God, The Tree of Life, The Life of St. Francis, trans. Ewert Cousins (London: SPCR, 1978), 278-279.

- 2Leo Steinberg, La sexualidad de Cristo en el arte del Renacimiento y en el olvido moderno (Madrid: Hermann Blume, 1989), 25.Blume, 1989), 25.

- 3Aurelio de Santos Otero, Los evangelios apócrifos (Madrid: Biblioteca de Autores Cristianos, 1991), 159, 205, 256, 304.

Fig. 1 Peasant with a Fruit Basket from a Neapolitan Nativity Creche, second half of the eighteenth century, wire-frame figure lined with burlap that connects the extremities, carved in wood or in baked clay, height: 11 in. (28 cm). Museo de Historia, Madrid. Acessed via Digital Library Memory of Madrid - CC BY-NC.

Fig. 2 Baltazar Figure from a Neapolitan Nativity Creche, second half of the eighteenth century, wire-frame figure lined with burlap that connects the extremities, carved in wood or in baked clay, height: 13.8 in. (35 cm). Museo de Historia, Madrid. Acessed via Digital Library Memory of Madrid - CC BY-NC.

Fig. 3 Young Peasant with a Basket from a Neapolitan Nativity Creche, second half of the eighteenth century, wire-frame figure lined with burlap that connects the extremities, carved in wood or in baked clay, height: 7.8 in. (20 cm). Museo de Historia, Madrid. Acessed via Digital Library Memory of Madrid - CC BY-NC.

These gospels were the product of oral traditions that circulated among the first generations of Christians, but more extensive and fanciful folk narratives of Christ’s birth also developed in various Christian regions. Different cultures appropriated the biblical story and made it their own through the incorporation of idiosyncratic elements that have accrued over time and often represent anachronisms to the actual biblical period. European examples of this type are varied and artistically valuable; some of them are even famous. The nativity scenes created by Francisco Salzillo in Murcia, for example, are well known internationally, as are those of Portuguese artists such as Joaquim Machado de Castro and Antonio Ferreira. Neapolitan nativity scenes are similarly recognized globally. These European examples are the result of the spectacular eighteenth-century development of the nativity scene in the arts.1 The variety of characters to be found in these nativity scenes is almost infinite. Standing before these works of art—at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York or in Spanish and Italian convents during Christmas time, for example—one can spend hours observing all of the scene’s details, such as the little figure of the butcher cutting meat and the woman buying it, the baker putting dough in the oven, the pasta seller hawking his wares, children fighting and playing in the streets while the policeman tries to maintain order, couples flirting in a corner, etc. These nativity scenes were originally made to decorate royal palaces or the homes of noblemen and the wealthy, but poor families and communities also produced handmade popular versions composed of objects collected from nature such as shells, straw, flowers, and sticks. In these nativity scenes, the objects vary greatly in size and style. They demonstrate the popular passion, inventiveness, and care imbued in the genre (See Figs. 1-3).

Christmas nativity scenes made in the nineteenth and early-twentieth century in Santiago are examples of the more “popular” type, a term used to catalogue anonymous crèches, not associated with any particular family. These “popular” nativity scenes exist in juxtaposition to crèches with known owners, which would typically be composed almost entirely of polychrome wooden sculptures made in Quito of the so-called Quito School, characterized by the use of veristic glass eyes and naturalistic flesh tones. Even today some elite families own nativity scenes with eighteenth-century figurines made in Quito, and some museums, like the Museo Votivo de Maipú in Santiago, exhibit quiteño nativity scenes (Fig 4). In popular nativity scenes, by contrast, miniatures of different materials, origins, and sizes lived together.

In assembling “popular” nativity scenes, families complement statuettes with diverse objects from other places and times. For instance, a nativity crèche might have three figures representing of the Holy Family bigger in size than the surrounding objects, which would usually be little clay statuettes, wooden stalls and carts, and miniature straw baskets, all made by local artisans. They also had wheat sheaves, seashells, silk flowers, and eighteenth- and nineteenth-century filigree adornments. The eclectic quality resulting from the combination of figures from different eras and the diversity of people interacting with them over time guarantees the meaning and relevance of the genre and grants it a capacity for constant growth and change. Anyone can approach this space and participate with their personal gifts and talents in their own crèche. Participating in the preparation of a nativity scene allows everyone to be part of the divine mystery. Ian Boxall claims that the act of reading of the Gospel of Luke, with its description of the birth of Jesus, is an invitation to enter into the nativity and become one of its participants.2 Readers of the gospel, like the shepherds, thus transform from observers of the holy birth to proclaimers of the arrival of the Baby Jesus. If the mere act of reading the Gospel of Luke’s account invites the reader to enter the manger, the act of assembling a nativity scene brings the individual into the holy moment to an even greater degree. Creating a sacred space was a way to repeat and recreate God’s exemplary work.3 Once created, the contemplation of the crèche was also an invitation to experience the numinous. As Diane Apostolos-Cappadona writes, “through its natural action of capturing and freezing the meaning of a ritual or a religious experience, the visual arts promote a re-experiencing of the original encounter.”4

The miniature world of the nativity scene provides an opportunity for its viewers to imagine themselves within the holy narrative.5 Creators of nativity scenes represent themselves as contemporary participants within the historic event. The belief in the historicity of the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem allows the practices of bestowing historicity on the nativity scene to continue and to project into the future. Since a person from any era can insert themselves and their environment into the scenery of the nativity, the possibility of being part of this event is limitless. Furthermore, as the iconographic sources of the nativity scene are centuries old, they perpetuate and incorporate anachronisms. In 1877, the Santiago newspaper El Estandarte Católico defended the presence of anachronistic elements of contemporary life in scenes of the birth of Christ, arguing that “the greatest anachronisms only serve to expand the spirit: criticism retreats in the presence of such burning faith and simple, unpretentious virtue.”6 In this way, the spectator becomes convinced that this story could occur in their own time and that they has the opportunity to participate. Society puts itself on stage.7 Or as Arnaldo Pinto Cardoso has written of Portuguese nativity scenes, “he who beholds the nativity scene must think that the divine mystery is possible during his time and in his world; and for this reason not only are there contemporary, idiosyncratic personalities in nativity scenes, but all elements that affect human life are included: space, flowers, fish, mountains and homes, creating real pictures of popular customs.”8

- 1Arnaldo Pinto Cardoso, “Navidad lusitana,” Revista FMR 75 (2004): 20-25.

- 2Ian Boxall, “Luke’s Nativity Story: A Narrative Reading,” in New Perspectives on the Nativity, ed. Jeremy Corley (London: T&T Clark, 2009), 36.

- 3Mircea Eliade, Lo sagrado y lo profano (Barcelona: Paidós, 1998), 29.

- 4Diane Apostolos-Cappadona, “Visual Arts as Ways of Being Religious,” in The Oxford Handbook of Religion and the Arts, ed. Frank Burch Brown (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

- 5Giorgio Agamben, Infancia e Historia: destrucción de la experiencia y origen de la historia, trans. Silvio Mattoni (Buenos Aires: Adriana Hidalgo, 2007), 189.

- 6El Estandarte Católico was a conservative newspaper established in 1874 which represented the Church’s need to participate in politics through the press. The Church used it to face the growing secularization of society. The abundant appearance of this and other newspapers in this article explains how they were one of the most preferred media outlets to circulate ideas and information in the epoch under consideration in this article. El Estandarte Católico (Santiago), December 24, 1877. All translations from the Spanish by the author.

- 7Oscar Cornago Bernal, “La teatralidad como paradigma de la Modernidad: una perspectiva de análisis comparado de los sistemas estéticos en el siglo XX,” Hispanic Research Journal 6, no. 2 (2005): 159.

- 8Arnaldo Pinto Cardoso, “Navidad lusitana,” Revista FMR 75 (2004): 25.

Representation of society

Nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century nativity scenes from Santiago reveal the values of rural Chile both in terms of the scene on which they are staged and the personalities they contain. This was a traditional agrarian society that had just begun to modernize. Nevertheless, an important part of the population could not enjoy this modernity and still lived in the rural surroundings of Santiago; others could afford the benefits of modernity but still longed for those days of rural life.

Many items present in these scenes are taken from the countryside and appear as miniatures of different materials: wooden stirrups, straw baskets full of fruit and/or flowers, terracotta animals such as pigs, cows and donkeys, and real wheat. In a photograph from the beginnings of the twentieth century of a detail of a crèche, we can observe a space crammed with diverse objects which form a Chilean picture. In the foreground, collected seashells are displayed along with a straw basket, a wooden barrel, leaves and stones, and a clay miniature of a woman eating bread, among other objects. A little huaso (Chilean cowboy) seated on a wicker chair, close to a table with a white, crocheted tablecloth, calls our attention. Then we see Quinchamalí ceramics, characterized by black and white designs obtained by putting the clay directly into fire and named for the small town where they have traditionally been manufactured. In the background a pair of oxen and a farmer are crossing a bridge made of little sticks; cardboard is used to make a mountain, a form popular in other Chilean visual and literary representations as a way of situating the Nativity within Chile’s rugged terrain (Fig 5, see Figs. 6-8 for details of this and other similar crèches). A rural imaginary prevails in this composition. This does not mean that agrarian and urban settings should be studied as oppositional phenomena, quite the contrary; they come across visually as complementary ways of inhabiting the world. I will focus on the rural not as a mere stepping-stone to the urban, but rather as a dynamic way of life capable of ascribing meaning and living in tandem with other realities.

Fig. 6 Popular Chilean Nativity Creche, Santiago de Chile, early twentieth century, photograph. Archivo Fotográfico Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile.

Fig. 7 Popular Chilean Nativity Creche, Santiago de Chile, early twentieth century, photograph. Archivo Fotográfico Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile.

Fig. 8 Popular Chilean Nativity Creche, Santiago de Chile, early twentieth century, photograph. Archivo Fotográfico Universidad de Chile, Santiago de Chile.

Although Santiago supposedly transformed in the last years of the nineteenth century into a more modern and urban society, the rural continued to predominate in cultural production—or “representations,” to use Roger Chartier’s term. Chartier’s ideas about the confluences of the social reality and certain aesthetic forms of representation are enlightening. The French historian insists that “representations” (mental, literary, iconographic, etc.) participate entirely in the creation of their reality.1 Cultural representations begin with a reality they hope to represent, but they are also accomplices in producing and organizing the experiences they convey. Along these lines, Gisèle Freund, writing on photography and its relationship to the environment, argues that each society produces defined forms of artistic expression that to a great extent are simultaneously based on and reflect requirements or traditions.2

It is important to note that although nativity scenes are material and representational objects, they are not passive. In historiographical terms, these artifacts provide information about how society wanted to be depicted or interpreted itself when interpreting the birth of Jesus. In developing different performances with and around nativity scenes, the creators of these objects and those who interacted with the completed assemblages developed a unique way of partaking in the Christian celebration. Materiality is inherent to human experience and part of its context; it is therefore a fundamental aspect in the production of culture. In this sense, the material and the intellectual/spiritual are not opposing forces, but rather part of a continuous space of reception and production where both aspects are important.3 In this essay, understanding these ideas offers the possibility of implementing a methodology that looks for commonality among religion, social reality, literature, and forms of visual representation.

Melissa Calaresu makes use of a methodology similar to that described by Chartier to study eighteenth-century urban life in Naples and its relationship to popular etchings, travel literature by foreigners who visited the city, and the characters that appeared in eighteenth-century Neapolitan nativity scenes.4 Calaresu’s analysis of literature, travel narratives, and cultural “types” inspires my own analysis of nineteenth-century Chilean nativity scenes, in which I employ similar sources. She builds on the importance of foreign travelers’ voices and perspectives in shedding light on popular types and stereotypes that shaped the city’s identity and argues that, in the eighteenth century, the application of the concept of the picturesque moved from the landscape to cultural types.

Examination of nineteenth-century descriptions of Chilean nativity scenes, as well as other contemporary sources, demonstrates that the inhabitants of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century Santiago appreciated and clung to a traditional society very closely connected to the countryside. Period visual imagery—contained in photography, paintings, drawings, and ceramics, as well as the literary imaginary—poems and popular songs—was fed by characteristics of rural Chile, which left their mark on the country’s cultural manifestations, including in urban settings.5 Rural identity predominated in the imaginations of Santiago’s citizens.

The choice of so many characters and elements coming from the countryside has to do with the self-representation of a group of inhabitants of Santiago as well as the longing of other groups of society for a rural life in danger of disappearing. The latter is embodied in literature, paintings, and the creation of nativity scenes which exemplify costumbrismo and the picturesque as an aesthetic category.6 In broad terms, Latin American costumbrismo was a nineteenth-century artistic genre which sought to depict the national soul or identity through the representation of popular types drawn from everyday life and local traditions. Although there are differences between countries, some shared characteristics can be observed. Eighteenth-century casta paintings (a genre of painting made predominantly in Mexico depicting categories of racial mixing) and the visual production of European travelers coming to America during the colonial period served as precedents to be used later by Latin American elites longing for past epochs. Like casta paintings and European travelers’ representations, costumbrismo consistently reduced heterogenous realities to a limited iconography of select characters and virtues, focusing on the rural imaginary in the Chilean context. Costumbrismo was a way to see the world both from ideas and the visuality associated with those ideas. In a dialectical way, the visual and mental nourished each other: from the one side, an idealizing spirit approaching the countryside and its traditions and from the other side, their materialization in visual and literary forms. This may explain why rurality was widely valued, both by those individuals who directly experienced the countryside every day and by those citizens that longed for a past when traditions were important.

- 1Roger Chartier, “La Construcción estética de la realidad. Vagabundos y pícaros en la Edad Moderna,” Tiempos Modernos. Revista Electrónica de Historia Moderna 3, no. 7 (2002): 1-15.

- 2Gisèle Freund, La fotografía como documento social (Barcelona: Editorial Gustavo Gili, 1993), 7.

- 3A good essay and review of the new academic trends in studies of material culture can be found in Andrew Jones and Nicole Boivin, “The Malice of Inanimate Objects: Material Agency,” in The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture, ed. Mary C. Beaudry and Dan Hicks (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012).

- 4Melissa Calaresu, “Collecting Neapolitans: The Representation of Street Life in Late Eighteenth-Century Naples,” in New Approaches to Naples c. 1500-c.1800, ed. Melissa Calaresu (Farnham: Ashgate, 2013), 175-202.

- 5Although the district of Santiago was home to only 21% of the rural population, the rural was nonetheless present in imagery of the period.

- 6Pablo Diener argues that it is difficult to give a universally valued definition of the picturesque. At first, it was a category used in reference to painting; but then evolved to be a concept to describe what is entertaining for the sight and stimulating for the senses. Pablo Diener, “Lo pintoresco como categoría estética en el arte de viajeros. Apuntes para la obra de Rugendas,” Historia 40, no. 2 (2007): 285-309.

Rural popular types in the nativity scenes

The first sign of this rurality can be appreciated in the presence of certain rural character types in all of the era’s nativity scenes. One of them is the huaso, the typical character of the Chilean Central valley (Figs. 9-12). He was depicted among agricultural crops and handling cattle; his essential clothes consisted of a hat with a round rim, traditionally black but also could be light colored when they were made with straw, called a chupallas, knee-high leather boots with spurs at the heels, a short jacket, and a poncho covering the jacket.

The huaso is ubiquitous in other artistic media, alerting us to his pervasive presence in contemporary Chilean reality and imagery. Surviving huaso figurines attest to their use in nativity scenes of the era, as do references to the presence of huasos in nativity scenes in lira popular (a late-nineteenth–early-twentieth-century Chilean style of poetry) and press excerpts. A poem like the following, made to be recited in front of a nativity scene, places the huaso in the role of a visitor to the manger, bringing gifts for the Christ Child and his parents:

A wagon of fruit

I bring to you, said a huaso,

to you, doña María [the Virgin Mary],

to neutralize the grease.

Pears, figs and cherries

Mr. Moscoso has sent

So that you might take them

and share them with you husband.

Finally, I bring you diapers,

clothing and a hat

to bundle up as soon as possible.1

In 1897, the lay newspaper El Chileno described a nativity scene that incorporated three Chilean huasos riding horses while wearing colorful ponchos, large chupallas, sheepskin saddle mounts, lassos, and spurs.2 On January 7, 1898, the newspaper El Pueblo reported on Christmases past and described Mrs. Liberata’s nativity scene as having, among many other figures, three saddled horses at the ranch door and huasos with ponchos and spurs.3

- 1Juan Bautista Peralta, “Sobre el Nacimiento del Niño Dios,” La Lira Popular Núm. 35 (Chile: [Imprenta de La "Ilustración Militar"], [1901?]), Archivo de Literatura Oral y Tradiciones Populares/Colección Alamiro de Ávila, Biblioteca Nacional de Chile. Available at Biblioteca Nacional Digital de Chile http://hdl.handle.net/10079/2170f7cf-4c34-43e0-9cf1-328570ab8001. Accessed December 29, 2021.

- 2“La Pascua. Cuadros al pasar,” El Chileno (Santiago), December 25, 1897, no. 4149.

- 3El Pueblo, January 7, 1898, no. 332.

This popular Chilean archetype also appears in two-dimensional representations of the nativity scene. At the middle of the twentieth century, artists began painting a world that was slowly disappearing. When some groups were experiencing nostalgia for a traditional and rural life of the century before, they used the huaso as a tool for depicting that lost world. These groups were searching for their own version of authenticity, which was seen related with the rural world, its artefacts, its characters and traditions.

In the middle of the twentieth century, huasos began to disappear from the capital, increasingly becoming a symbol of the rural territories. Influenced by mid-century nostalgia for Santiago’s rural past, artists visually argued for the importance of rurality to Chilean national identity. As Ricardo Bindis has argued, the huaso in twentieth-century painting is a legendary proponent of the vernacular cause, interpreter of rural labor and of the beliefs, superstitions, and rituals of its people.1 The work of painter Arturo Gordon (1883-1944) is particularly representative of this trend.2 Gordon’s works portray the Chilean people as picturesque (Fig. 13).3 In one of his paintings, a group of women and children appear praying the Christmas novena (a nine-day prayer cycle) in front of a nativity scene, which, like contemporaneous press descriptions, perches atop a mountain made of cardboard and other domestic items. The main biblical characters are present. Behind them a group of huasos on horseback arrive to make offerings to the newborn baby.

- 1Ricardo Bindis, Pintura Chilena 200 años: despertar, maestros, vanguardias (Santiago: Origo, 2006), 181.

- 2Arturo Gordon studied drawing with Cosme San Martín, painting with Pedro Lira, composition with Fernando Álvarez Sotomayor, and sketching with Juan Francisco González. Gordon’s work is representative of the Generation of the Thirteen, which consisted primarily of students of the Spanish professor Fernando Álvarez Sotomayor. Sotomayor praised Gordon as the “Chilean Goya.” Three of Gordon’s works represented Chile in the 1929 Seville Exhibition. See Milan Ivelić, Pintura chilena: Colección Banco Central de Chile (Santiago: Banco Central de Chile, 2004).

- 3José María Palacios, Hernán Rodriguez Villegas, and Mario Fonseca, Pintura chilena 1816-1957: colección Roberto Palumbo Ossa (Santiago: Naker, 1998).

Fig. 13 Arturo Gordon, Novena del Niño Jesús (Novena of the Christ Child), early twentieth century, oil on canvas, 46 x 37 in. (117 x 94 cm). Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago de Chile.

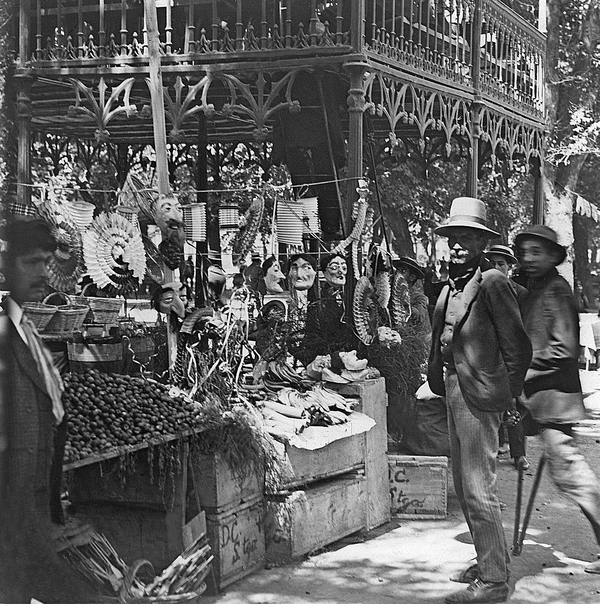

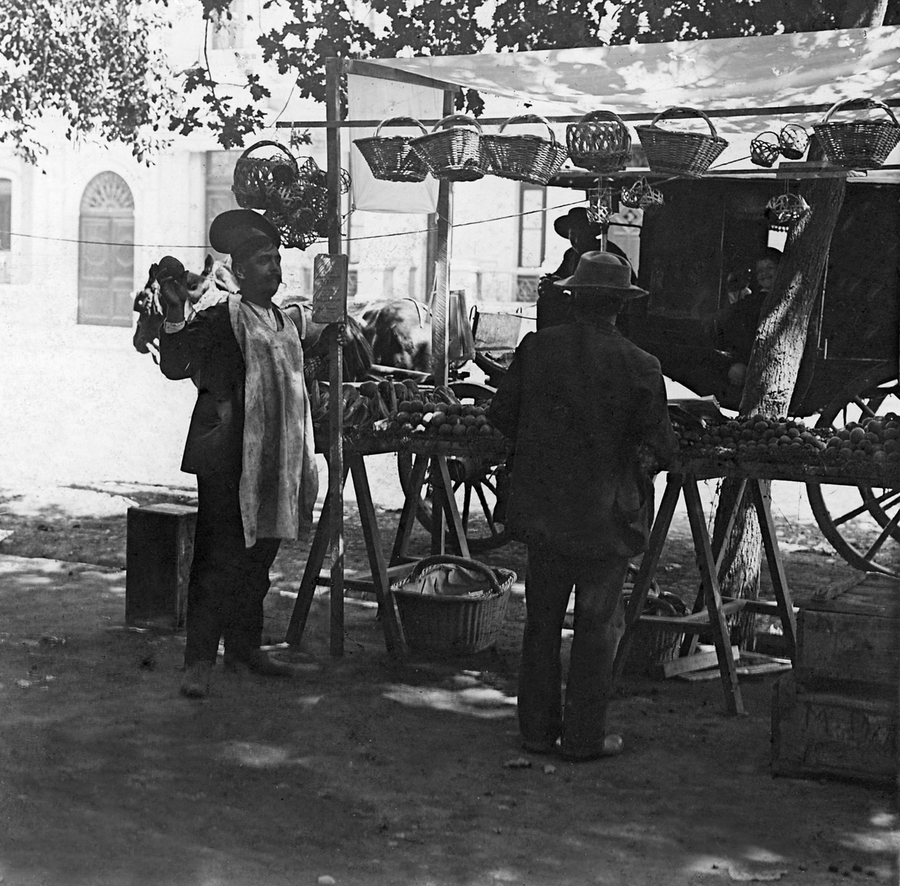

Photographs of manger scenes from the earliest moments of the twentieth century show huaso figures engaged in a variety of activities (Figs. 5-8). These photographs, along with written sources, paintings, prints, and surviving huaso miniatures, confirm the important role of huasos in nineteenth-century popular imagery. Clay huaso miniatures were sold at La Alameda, a central avenue surrounded by poplar trees that was converted into a boulevard at the beginnings of the Republican period. It crossed the entire city from west to east and was used for public promenades and festivities, such as Christmas markets. Some of these stands sold flowers, fruits, other comestibles, and clay figurines depicting popular characters (Fig. 14-15).

In Figure 14, for example, we see what appears to be a family, posing in front of the camera. They are formally dressed, adult men wearing hats and the boy donning a white garment. The youngest lady’s head is covered, in line with contemporary codes of etiquette. The family shows off the table they have spread with a white tablecloth and then set. The little figures they sell are put on the table in a scenographic way, using different levels in order to help the spectator-client view them all. Looking from top to bottom, we see a wicker basket, filled with percussion instruments called matracas is perched on a straw chair. Children used these popular instruments to run through the streets making noises during Christmas time. A level down we see a bull or a cow, followed by another with a dog and a group of huasitos riding horses; there are more floors with other animals and yet more huasitos.

The choice of some photographers to document the old-fashioned modes for celebrating Christmas can be appreciated in these unique early-twentieth-century photographs. The photographs give information on the different figurines sellers sold in their stands at this time (Figs. 16-17). Manuel Domínguez’s (1867-1922) photographs, for example, offer a record of Santiago street life during the Christmas season. His images of La Alameda show it lined with stands selling flowers, fruit, and fried food, as well as the figurines. One nineteenth-century photograph by Domínguez shows a fruit vendor and his stand surrounded by rural items that had traveled from the towns of Renca, Colina, and Quilicura north of Santiago to supply the capital city. The shopkeeper stands amid baskets of all types, also for sale.

The ceramic figurines sold at stalls on La Alameda were made by women artisans. They had inherited a unique tradition developed predominantly by the Franciscan nuns of the convent of St. Clare (Santa Clara) in Santiago, although others were created by unknown artists in the south of Santiago. Generally speaking, it is the ceramics made by the nuns of St. Clare, with their origin in the colonial period, that best represent the variety of personalities of the era’s society. The nuns were famous for their handmade crafts; they made both sweet pastries and ceramics. The nuns sold their wares at special stands along La Alameda on the days leading up to Christmas and the ceramics were also known as the “nuns’ little pots” or the “little clay figures.”1 According to a December 24, 1885 article in the Santiago newspaper El Mensajero, parents bought figurines to give to their daughters with this dedication: “This negrito [a reference to Balthazar, one of the three wise men, who is typically depicted as dark-skinned or African] is for you so you don’t forget your love [negrito]; this little horse is for you, so-and-so, so you will go dance; this little lamb is for you, so-and-so, so you will be less severe.”2

Other visual representations complement the information supplied by early-twentieth-century photographs, paintings by Chilean artists, and news stories from the period about nineteenth-century nativity scenes’ capacity to reflect the young nation’s identity. While aristocratic nineteenth-century Chilean painters produced bourgeois European-style landscapes and portraits and authors penned novels narrating the urban life of the European-descended elite, a new generation of artists who replaced them in the early-twentieth century moved away from this European-inflected style to focus on what was uniquely Chilean. These artists conveyed Chilean national identity in the form of criollo (creole) literature, costumbrista painting, and vernacular music. Instead of depicting the aristocracy and their foreign manners, this new generation of visual and literary artists valued customs coming from the people. This generation of artists and writers searched for the roots of an authentic Chilean identity, which they situated primarily within the rural world and its traditions. The diverse manifestations of cultural production of the era all present the same rural world that can be appreciated in the nativity scenes. The residents of Santiago inhabited this rural environment and experienced the nativity scenes within this context. Santiago’s inhabitants presented themselves before the nativity scene as rural persons, offering objects that embodied this rural quality.

Chilean artists were not alone in focusing on vernacular characters. Foreign artists who settled in Chile or came to visit also left documentation of their impressions in the form of paintings and drawings. It was not just the local eye that reflected the importance of the rural, but also that of the foreigner who came to Chile. The traveling artist came to the Americas to investigate a landscape perceived to summarize the singularities of the regional physiognomy, documenting individuals representative of a particular society, and the emblematic manifestations of their history and material culture. In sum, the foreign artist incorporated everything that allowed for the construction of a typical identification of a country or a region.

- 1On craftwork, see María Bichon, En torno a la cerámica de las monjas (Santiago: Imprenta Universitaria, 1947).

- 2“Este negrito para que usted no olvide a su negrito; este caballito para que usted, fulanita, vaya al resbalón; este corderito, zutanita, para que sea menos tirana.” El Mensajero (December 24, 1885).

Fig. 18 Johann Moritz Rugendas (Juan Mauricio Rugendas), El huaso y la lavandera (The Huaso and the Washerwoman), ca. 1835, oil on canvas, 11.8 x 9 in. (30 x 23 cm), 1835. Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Santiago de Chile.

One example is German painter Johann Moritz Rugendas, who depicted many characters and themes related to Chilean identity over the course of his prolific career as a visual artist.1 Popular Chilean figures, particularly the huaso, appear frequently in his work. Rugendas came to South America to capture typical landscape scenes and popular characters and customs of the newly-formed Latin American republics. Like many artists of his time, Rugendas initially came to South America as part of a scientific expedition. He accompanied Baron George Heinrich von Langdorf to Brazil and then proceeded to travel solo throughout South America, depicting its geography and characters. He liked Chile so much that he spent many years traversing the territory and working on prints, drawings, and canvases depicting its idiosyncrasies. Rugendas painted works such as El huaso y la lavandera (The Huaso and the Washerwoman) (Fig. 18) and Rodeo de huasos maulinos (Rodeo of Huasos from Maule), and several lithographs with huaso protagonists, such as La Topeadura (a topeadura is a contest in which two huasos on horseback attempt to unseat each other from their horses).These paintings became very famous in Chile and are part of the Chilean national imaginary, even appearing in school textbooks.2

Not all popular types appeared in as many varied forms as the huaso did. Nonetheless, there are also depictions of the singers, harpists, women who make bread in mud ovens, and vendors of mote (a sweet beverage made of boiled and husked wheat). As with the huaso figurines, nuns and other women made much-loved ceramic figures depicting these popular characters. Similarly, some Chilean artists represented these figures in two-dimensional form (Figs. 19-25).3

- 1The main and most important source to study Mauricio Rugendas in Chile is that of Pablo Diener, Rugendas su viaje por Chile, 1834-1842 (Santiago: Origo, 2013).

- 2Huasos appear in the work of many other foreigners as well, including works by Theodore Blondeau, Louis Francois Lejeune, and Alcides Dórbigny. For more information, see Pedro Ruiz Aldea, Tipos y costumbres de Chile (Santiago: Editorial Zig-Zag, 1947).

- 3Sylvia Dummer, “Los desafíos de escenificar el alma nacional. Chile en la Exposición Iberoamericana de Sevilla,” Historia Crítica 42 (2010): 92.

Harpists also appear in both ceramics and paintings. Harpists, usually from the countryside, are typical of Chilean history, since the harp is one of the most representative instruments of Chilean musical tradition.1 Originating among the bourgeois, during the nineteenth century the harp became the central instrument at fondas and chinganas—two kinds of popular celebrations involving dance, alcohol, and music. Harpists also play at rural festivals marking the agrarian cycle and at Christmas parties. In the central region of Chile, the harpist is consistently linked in iconography to the figure of a singer.2 As evidence of the importance of these popular types in the Chilean social imaginary of the period, ceramic figurines of singers and harpists made at the beginning of the twentieth century survive to this day and early-twentieth-century photographs show such figurines for sale on La Alameda. Photographs from the beginning of the twentieth century show harpists at popular fondas; caricatures from the time draw on familiar Christmas imagery to make social critiques.

Singers and harpists also appear together in Arturo Gordon’s paintings and, later, in works such as Marco Bontá’s 1929 La novena del Niño Dios (The Novena of the Christ Child) (Fig. 26). As mentioned above, Gordon participated in the movement searching for a rural and authentic Chile, painting works depicting Christmas celebrations in popular settings. Inspired by his longing for a rural and “authentic” Chile, he depicts what used to be typical and representative. In his paintings, Gordon portrays the same popular types that appear in manger scenes, popular songs, photographs, and lira popular. Another work by Gordon, La Zamacueca (zamacueca is a style of dance), incorporates popular types in action, among them harpists, guitarists, and huasos. Similar in theme and content is La Zamacueca by Manuel Antonio Caro (1835-1903). These works are further evidence of the presence of characters such as the harpist, guitarist, and huaso in the Chilean social and visual imaginary.

Offerings from the countryside

The offerings of seasonal fruits and flowers described in popular literature and the objects that appear in Christmas-themed photographs offer further examples of rural imagery. As I described in the photographs mentioned before, miniature wheat sheaves, fruit baskets, stirrups, and large and small animals all appear as part of nineteenth-century nativity scenes. Teams of oxen and small ceramic pigs typical of the village of Quinchamalí also appear in nativity scenes (see Fig. 5). The Christian belief in the dual nature of the Christ child imbues these offerings with new meaning. God, who becomes man and is embodied in the form of a small child, must be cared for, fed, and relieved of his poverty. The gifts form a bridge between two worlds, allowing God to live among his people. Everyone presents the best they have to give in order to participate in this human and divine coexistence. These practices insert themselves in the tradition of giving gifts to baby Jesus as the popularly interpreted tradition of the apocryphal evangelists and as the result of freely expressed religious piety felt by a people who participate in the mystery of this celebration, supplying a variety of elements from their surroundings.

In songs and Christmas carols, products of the land and their associated tools take on symbolic value as special gifts. These presents made to the baby Jesus elevate quotidian objects to a divine level, taking on supernatural meaning and becoming worthy of being given to God. Each of these offerings reflects the best that land—and its people—have to offer. When the highest quality fruits and vegetables of the season are put at the foot of the altar or the crib, they are given ritual treatment as a path toward the sacred; no longer are they mere objects, they have become spiritual gifts.

To be chosen, these objects must be culturally significant. Objects offered to the Christ Child must be carefully considered and evaluated; the choice of objects to symbolize nature and daily country life is not casual. For this reason, the verses, carols, and novenas from literature, and nativity scene decorations, representing the visual arts, are full of birds, suns, stars, flowers, fruits, and tools that allude to natural surroundings. Chilean nature was present in popular religiosity and, more precisely, in the veneration of the Christ Child. Many hymns sung to the baby Jesus incorporate fruit and flowers from the countryside as offerings to the child, employing a very Chilean vocabulary and language.

Chilean natural objects are also present in nativity scenes by way of small figures made from a variety of materials that symbolize the land and its products. They enter the sacred space of the nativity scene because they are also considered sacred. In the popular mindset of the epoch, these were containers for all the sacredness nature is able to contribute. The sheer number of fruits and vegetables in photographs alongside the jugs and tools, everything decorated with flowers and wheat sheaves, demonstrates the mundane nature of these objects and their ability to symbolize the special aura they have in a rural, traditional society (see, for example, the wheat sheaves in Fig. 5 or the character holding a basket in Fig. 7). As this verse of lira popular, created and sung by women and children in front of nativity scenes, demonstrates, religious media constantly referenced Chilean nature and seasonal fruits:

Good night Mariquita [nickname for Mary]

Although I am very late

I am bringing many gifts

For your beloved baby.

Apricots, cherries and pears

I bring you, Mariquita,

Blankets and diapers.1

- 1Juan Bautista Peralta, “Tonadas para el Niño Dios,” La Lira Popular Núm. 57. Preparativos i exijencias de las niñas para la Pascua. Choque de trenes (Chile: Imprenta “El Debate,” [1902?]), accessed December 29, 2021, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/ecde941a-5797-4d46-985c-2305924f4510.

Inventiveness out of poverty

The nativity scenes display the ingenuity and inventiveness of a stratified society. Some families could afford to buy pieces from Quito or Peru, where the most valuable and finely made sculptures of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century South America were produced. Most people, however, had little money, had not inherited imported nativity figurines, and lacked the resources to purchase them from Europe or buy them in the new, expensive stores in Santiago. Instead, they used regional materials to create colorful handmade nativity scenes full of local flavor. As one newspaper of the time claimed, the poorer the nativity scene, the more original it was.1 The anonymous author of a December 24, 1877 article in El Estandarte Católico elaborated:

Nothing is more poetic or more tenderly beautiful than a manger scene. I am not referring to the fancy versions of devout wealthy people, but to those holding places of honor in the shanties of humble people. Every aspect of these is special—the decor and figurines, the main actors and details, the baby, the wise men, Joseph, the Virgin, and the women of Bethlehem. Each one is fresh as if to say, “Eat me.” The first fruits of the year: the golden apricot lends its scent to its surroundings, almost envied by the flowers. The cherries offer their rich color; the fig covers its fiery heart under a black mourning veil; the peach whets appetites and the wheat’s first spikes grow in a modest jar, caressed by crystal fountain waters. Basil here, the tender sensitive [sic—sensitiva, perhaps the Mimosa pudica, known in English as “the Sensitive Plant”] there, lilies over here, roses and jasmine over there, the garden’s finest [plants] have been chosen to venerate the nativity scene that, as his cradle, honors the Savior of the world.2

The author describes what could be found in charming and novel nativity scenes as true poetry, where simplicity, as extreme as it may be, was no obstacle for composing a lovely assemblage.3

Each family created their nativity scene according to their means and enjoyed the simple pleasures of this tradition. Another description of the event in El Estandarte Católico evocatively describes—from a Catholic point of view—the variety of characters that might appear:

A manger scene is always novel and interesting, even when not entirely unique in its details. . . . of particular note are the wise men nestled among a deck of cards; they cross cork hills and fabric forests to worship the child. A fiery, robust Maritornes [an ugly character from Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quijote] converses with Joseph, the Virgin, and the Baby next to a black woman with white ivory teeth, red lips like smoldering iron and two eyes like chasms releasing sparks and flames, who is taking bread out of an oven with a paddle as big as her body. Among grey gauze clouds, a candle spouts smoke, representing the eastern star. The child is surrounded by cows, sheep, etc., who warm him with their breath and seem to be arguing about the best place to stand. There are always elephants as small as mice fiercely battling lambs the size of mastodons.4

This quotation conveys the inventiveness people developed creating their own nativity scenes. They gathered pieces from various sources to assemble the scenery. The result included pieces of different sizes and materials. This same effect can be appreciated in photographs from the beginnings of the twentieth century (Figs. 5-8). Miguel Luis Amunátegui—a nineteenth-century Chilean liberal historian and politician—described the public’s strategies for incorporating, alongside figures canonic to the event, popular characters and figurines made from a variety of materials, which to him even seemed grotesque.5 Housewives pulled cloth angels, fine figures, ceramics made by nuns, and wooden houses out of trunks, using their ingenuity to assemble manger scenes from the objects they had available to them.6 El Estandarte Católico highlights the value of simplicity, as well:

Wherever one goes, there are a limitless number of poignant and simple rustic scenes. Days ahead of time, children prepare their whistles, flutes, kazoos, tambourines, horns, and drums to celebrate the newborn baby. Echoes of their popular performances hit the air and make for an extremely lively night. On certain occasions, one can visit the famous nativity scenes, entirely novel and charming, where simplicity, as extreme as it may be, ensures that everyone experiences this true, noble poetry.7

As this source suggests, inventiveness and austerity exemplify the spirit of the era.

- 1El Estandarte Católico, December 24, 1875.

- 2“Noche Buena,” El Estandarte Católico, December 24, 1877.

- 3El Estandarte Católico, December 24, 1875.

- 4El Estandarte Católico (Santiago), December 24, 1875.

- 5Miguel Luis Amunátegui, Las primeras representaciones dramáticas en Chile (Santiago: Imprenta Nacional, 1888), 24.

- 6“Los Nacimientos,” El Charivari, December 23, 1867.

- 7“Noche Buena,” El Estandarte Católico (Santiago), December 24, 1875.

Final reflections and conclusions

Santiago’s late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century population prepared nativity scenes for Christmas that represented their own world—a miniaturization of their surroundings. Their imagery and resourcefulness were used in service of their faith to celebrate the most important event of the Christian calendar, the birth of Christ, as a historic event.

Strikingly, until the late-nineteenth century and the beginnings of the twentieth, there appears to have been no difference between the nativity scenes of the general population and those of the upper classes, in the sense that they all depicted their surrounding world and historical era with great fondness. Those not comfortable with what modernity brought longed for those days where authenticity and traditions were important. The distinction among nativity scenes was solely in the materiality of the figurines. Moreover, everyone could enjoy the nativity scenes of others: citizens welcomed the populace into their homes, priests and nuns unlocked the doors of their churches and convents. The openness of this Christmas ritual and its location in the streets, made it inclusive and “Chilean” in nature. Christmas was often compared to the September 18th national holiday, because on both dates the people went to La Alameda to celebrate with Chilean alcohol and traditional dances, costumes, and songs.1 We even have some sources describing people shouting “Viva Chile!” at Christmas, a phrase more commonly heard on national holidays celebrating freedom from Spain.2

In the nineteenth century, Christmas was celebrated in a shared and homogenous manner and in a shared space on La Alameda, but towards the end of the 1800s Christmas celebrations in the public space became increasingly less inclusive. This shift was probably due to what Elisa Silva describes as the elite’s growing separation from the customs of the general population, which they came to consider barbaric, resulting in a gap between the practices of the population at large and those of the elite.3 Upper class Chileans criticized the upheavals and drunken revelry of Christmastime.4 As the elite distanced themselves from popular customs, they began instead to hold private parties at exclusive clubs. Thus, while the upper class had shared their leisure time with the lower classes until the mid-1800s, by 1870 the inauguration of new entertainment establishments for the oligarchy solidified the marginalization of popular leisure activities.5

The wealthy began to purchase nativity scenes in the new stores that had opened in the capital, moving away from the popular nativity scenes that characterized the taste of society during the colonial period and early Republican years. These new nativity scenes imported from Europe brought European characters with them to worship the baby Jesus, such as soldiers with German flags or a little Napoleon.6 In 1897, the newspaper El Pueblo even described figures brought from Rome and designed by an Italian artist.7 Nothing could be more distant from the huasos, mote vendors, flower sellers, and harpists who had accompanied the baby in the Christmas scenes and celebrations of the past. Still, these traditional figures continued to appear in the nativity scenes of the poorest people over the following decades. Modernization with its new customs had not yet arrived in all Santiago homes in the late-nineteenth century. Many poor people continued their popular and Chilean worship for years to come.

- 1“Novedades,” Las Novedades, December 25, 1875, no. 63. Also in “Novedades,” Las Novedades, December 26, 1878, no. 372.

- 2“La Capital,” Los Tiempos, December 27, 1880, no. 969.

- 3Elisa Silva, “La Nochebuena en La Alameda. Descripción de una tradición en tiempos de modernización. Santiago de Chile, segunda mitad del siglo XIX,” Historia 45, no. 1 (2012): 199-246.

- 4Olaya Sanfuentes, “Tensiones navideñas: Cambios y permanencias en la celebración de la Navidad en Santiago durante el siglo XIX,” Revista Atenea 507 (2013): 149-163.

- 5Daniela Serra, “Hoy es Nochebuena y la ciudad está de fiesta: la celebración de la Navidad en Santiago, 1850-1880,” Revista de Historia Iberoamericana 4, no. 2 (2011): 13.

- 6“La Pascua. Cuadros al pasar,” El Chileno (Santiago), December 25, 1897.

- 7“Crónica,” El Pueblo (Santiago), December 17, 1897.

Research for this article was funded by Fondecyt Project 1200553, "Esculturas de Madera del Niño Jesús en Chile. Investigación y análisis de la objetualidad de un artefacto religioso desde los llamados Estudios de la Cultura Material."

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2022.1

1. Olaya Sanfuentes, "Models of a Bygone World: Popular Nineteenth-Century Nativity Scenes as a Representation of Chilean Society," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2021), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.1.

Sanfuentes, Olaya. "Models of a Bygone World: Popular Nineteenth-Century Nativity Scenes as a Representation of Chilean Society." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2021), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.1.