Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Adjunct Associate Professor in the History of Art at the University of Pennsylvania, has combined teaching and museum curatorial work, most notably as Acting Head of the Sculpture Department at the National Gallery of Art in the early 1990s. A nineteenth-century French specialist, she has produced major museum exhibitions, catalogues, articles, and books on various topics. Among the most recent are Edgar Degas Sculpture (National Gallery of Art, 2010), co-authored with Daphne S. Barbour and Shelley G. Sturman, and her own Funerary Arts and Tomb Cult—Living with the Dead in France 1750-1870 (Ashgate, 2012), one of her various publications on French funerary issues (including for MAVCOR) since her 1983 dissertation on the subject. The present essay marks her new inquiry into deathways and funerary arts beyond France.

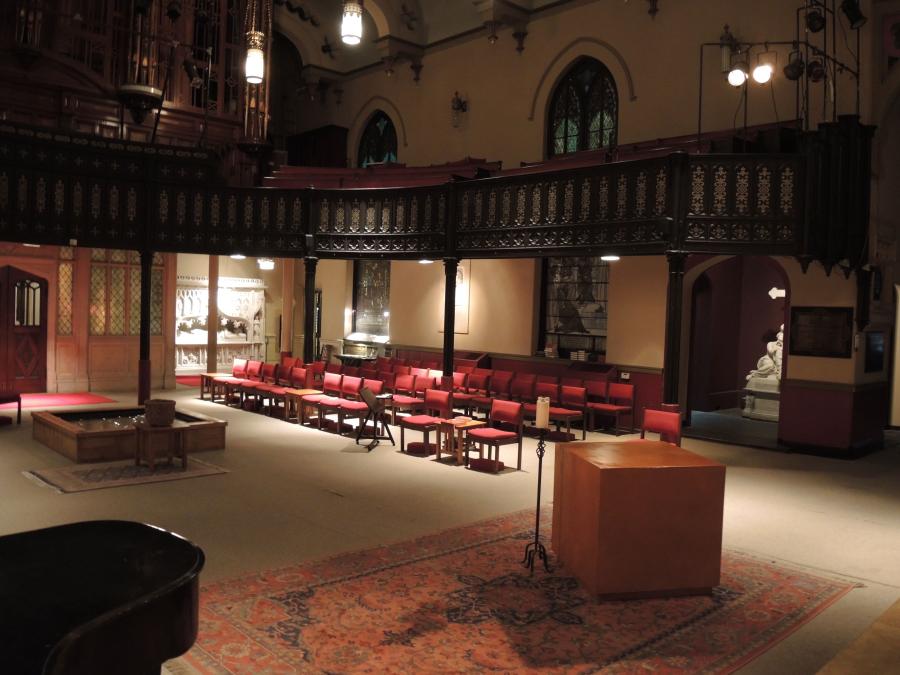

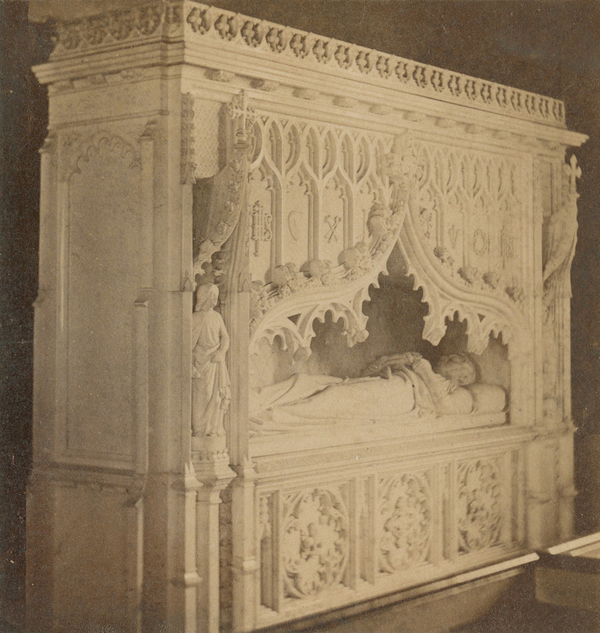

Passing through the north door of the inner vestibule at St. Stephen’s Episcopal church in Philadelphia leads to a startling encounter. Just past the door at left looms a white-marble Gothic-style monument.1 We are first struck by its proximity, only inches away as we enter, but continue to respond to its sheer presence. The form is more arresting than physically massive. At almost nine feet high by ten and a half feet long and about thirty inches deep, the monument is only a few feet taller than we are. Nevertheless, it commands the intimate space under the organ loft, insisting on our attention even without the artificial light that now floods its face.

Walking toward or standing in front of the monument triggers subtle forms of haptic awareness.2 Mind and gaze join gut, bones, muscles, nerves, and skin to explore the confrontation.3 All faculties focused, we probe masses and space which shape and animate this environment and engage us: the floor which supports and links us with the marble; the wall which anchors the monument jutting towards us; the expansive flat ceiling under the organ loft which compresses the surrounding space; the ample nave at our back; and the marble’s nearness, volumes and cavities, its ponderosity and temperature. We enter into gravitational tension with the ensemble as a form of subtle contact without touch.

At this close range, in such strong light, the marble displays its compressed crystalline matter as well as its elaborate carving and finish, traces of both dynamic nature and a judicious human mind and hand. The architectural frame is formally sophisticated, masterfully managing energy and space. It stretches horizontally from the vestibule door as an elegant rectangle, its profile animated by two corner tabernacles with nodding ogee arches that curve upward, tight against the mass. The surface ripples with gracefully ordered ornament: a cornice of delicate openwork, small figures in the corner tabernacles, and emblems in shallow relief within tracery. Delicacy gives way to the drama of the sweeping central canopy that presents a recumbent statue just within the raised niche.

We sense the heft and presence of that effigy, resting at waist height within easy reach. Yet the framed niche that displays the figure also withholds it. A Latin inscription across the plinth, incised in Gothic script, indicates the image embodies a devout Christian whose life spanned the late-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries: M. S. Eduardi Shippen Burd. Nat. octav. Kal. Ian. A. D. M.DCC.LXXIX. Ob. decim. quint. Kal. Octob. A. D. M.DCCC.XLVIII. In croce spes mea [Mr. Edward Shippen Burd. Born January 8, 1779. Died October 15, 1848. My hope is in the cross].4 The sculpture invites close scrutiny. Body, facial features, lush hair in decorative S-curves, and undulating fabric are powerfully modeled and pliant, credible as life forms while they impress as finely-worked marble. The human form and scale (seventy-eight inches) also grip us viscerally and psychologically as we contemplate the figure.

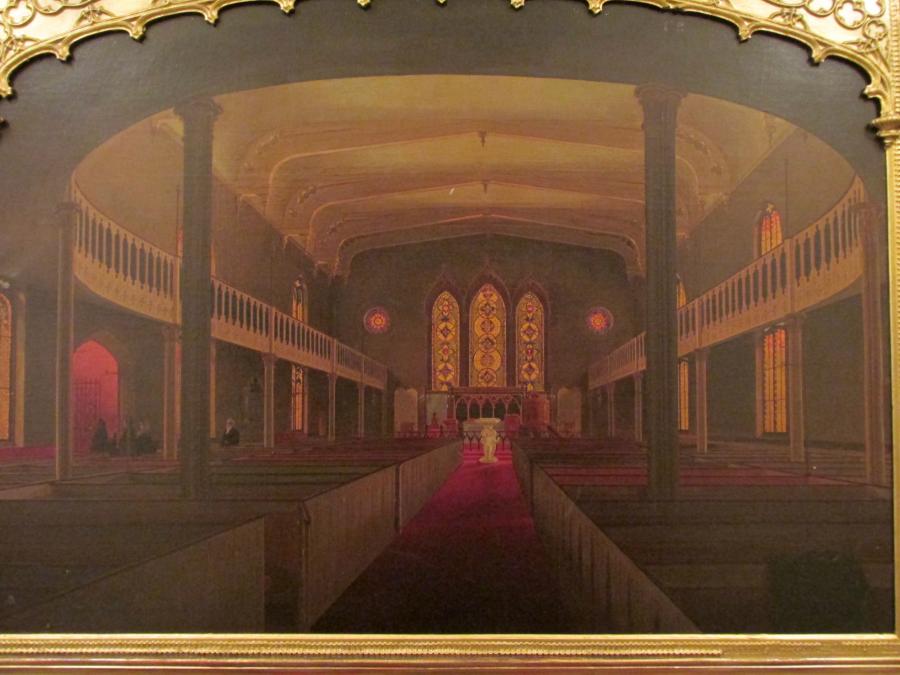

The statue faces forward as we approach but then presents a profile view when we stand in “front” of the monument. It embodies a handsome, mature man, rendered historically specific in the coiffure and muttonchops fashionable around the 1830s, yet removed from “then” by the neutral robe and drape across the lower body. Though the statue represents Mr. Burd in death, it suggests ease and awareness: the eyelids are partially open, the gaze focused forward (Fig. 2). The body appears in a startlingly un-Gothic posture that we might adopt while resting: the hands are intertwined on the chest and the feet are crossed under the drape. Looking at the architectural and sculptural ensemble from the chancel (Fig. 3), we become aware that the building embraces this luminous presence under the organ loft, featuring it at the very entrance as the sanctuary’s compelling spokesman about the afterlife.

- 1Using the same rhetorical device of a simulated promenade familiar in travel guides, the opening description of St. Stephen’s in Roger W. Moss, Historic Sacred Places of Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 132, similarly notes the impact of the monument upon entering. The formal analysis to follow builds on my training as a sculptor and later readings: Herbert Read, The Art of Sculpture (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1956); Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception, trans. Colin Smith (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962); a range of discussions of phenomenology and three-dimensional form in space, but particularly Kent C. Bloomer and Charles W. Moore with a contribution by Robert J. Yudell, Body, Memory, and Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977); F. David Martin, Sculpture and Enlivened Space: Aesthetics and History (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 1981); and Mark Paterson, The Senses of Touch: Haptics, Affects and Technologies (New York: Berg, 2007), doi:10.5040/9781474215831

- 2The term haptic (from the Greek “relating to tactile sensation”) appears in Aristotle’s work. Though it is most familiar as referring to direct contact, it has since evolved, with study from different perspectives, to more broadly signal an integrated system of bodily experience within an environment at varying distances. See, in particular, Paul Schilder, The Image and Appearance of the Human Body: Studies in the Constructive Energies of the Psyche (New York: International Universities Press, 1950; first published in 1935), doi: 10.4324/9781315010410; James J. Gibson, The Senses Considered as Perceptual Systems (Boston: Houghton Mifflin 1966); and Bloomer and Moore, Body, Memory, and Architecture.

- 3Martin, Sculpture, 53.

- 4Both life dates deviate from official records. Parish registers give Burd’s birth date as December 25, 1779, not January 8 (Christ Church Registers; Christ Church Historical Collections Online). A newspaper reports Burd’s death on September 17, 1848, not on October 15 (“Deaths,” North American [September 19, 1848]: 2).

Our experience within the church provides a glimpse of the original vision for this memorial. Completed in the 1850s, it formed a vital element of the building as a material, ritual, and symbolic entity that connected the divine and human. The architect of the Burd tomb, Frank Wills (1822-1857), emphasized this multi-faceted concept as his guiding principle for modern church design. Wills described it as such in his most important publication, Ancient English Ecclesiastical Architecture and Its Principles Applied to the Wants of the Church at the Present Day (New York: Stanford and Swords, 1850), a key treatise, then and today, adapting a variety of contemporary sources for use in modern Anglo-Episcopal America.1 The church, he argued, should be a site in which myriad material forms enabled the interaction of the divine and human. Architecture, monuments, liturgical objects, candles, chimes, and texts all functioned as manifestations of the Christian mystery, fusing the walls, ceiling, doors, and floor into a potent symbolic whole:

Christianity laid the broad foundation of its lengthened aisles, bade arch soar above arch, and all point up to heaven; wrote the incomprehensible doctrine of the Trinity on its front, and taught the same awful mystery in every part of the edifice; bids man when he crosses the threshold, humble himself to the dust, and awed into adoration, prostrate himself before his God.2

Wills’s imagined human engagement with the church is emphatically body-centered, biokinetic, and multi-sensory, fusing body, mind, and emotion. Signaling the importance of a memorial like the Burd monument within such a paradigm, the architect gave special prominence to the departed within the community of worshippers, and to funerary monuments within the church. In so doing, he challenged a phalanx of Americans hostile to such memorials as expressions of undemocratic elitism and un-Christian vanity in the modern American House of God, including a major contemporary authority on church architecture, the Episcopal Bishop of Vermont John Henry Hopkins, Jr.3

Wills promoted church monuments beyond their traditional roles as individual tributes and memory prompts. The interior monument, for Wills, inserted the departed within the sanctuary among the living. Church memorials, he maintained, “shall be ever before us,” a “connecting link between us who live . . . and those . . . who sleep in their quiet graves.”4 Wills, furthermore, upheld the Burd monument as a model for how such memorials might serve as vital components of the church’s doctrinal fabric and as teaching resources for emerging generations. Wills argued that the Burd memorial, employing one of the most elaborate types of church monument (an effigy tomb framed by an architectural canopy), gave commanding form, within the sanctuary, to Christian beliefs about death and the afterlife.5 In its prominence and inclusion within the fabric of the building, its message became that of the church. This particular American monument may even present an understudied alternative vision of the afterlife—one incorporating an intermediate phase just after death—that runs through Protestant and Anglo-Episcopal sources and can be linked, as a lived belief, directly to Wills’s patron and to the rector of St. Stephen’s.

By advocating the interplay in church architecture between the material and the human, present and departed, Frank Wills participated in a broader campaign to reassert an ancient Christian doctrine: to present the sacred invisible to the senses. The architectural pursuit of that goal, by adapting principles of Gothic architecture and medieval devotion, formed part of the mid-nineteenth-century phase of the Gothic Revival, a movement in which Wills played a central role in both England and America.6 He was a founder of, as well as official architect, critic, and theorist for, the most prominent organ of church architectural reform in the United States, the New York Ecclesiological Society (NYES), established in 1848. Originally from Exeter, England, Wills had been a member of the initial group of reformers around Cambridge, England who convened in 1839 and eventually took the name “Ecclesiologists” to signal their pursuit of “ecclesiology,” a term they invented for the study of church architecture, its meaning, and use.

Ecclesiologists sought to give architectural form to select principles promoted by scholars at Oxford, often dubbed the Oxford Tractarians for writings on the Anglican Church published from 1833 through 1841.7 They and their adherents sought to rebalance doctrines selected by the Church of England from those of earliest Christianity and the Reformation to provide a middle course between the perceived sins of Roman Catholicism and the austerities of the Calvinist Protestant camp. The group’s published arguments exacerbated tensions within the Protestant Anglo-American community that had developed since the secession of the Anglican Church from the Roman Church in the sixteenth century, with the evolution of high-church camps (advocating certain pre-Reformation traditions) and “low,” Protestant, or evangelical camps (adhering to a wide spectrum of Reformation positions).8

Much of the conflict pivoted on the perceived relationship between the sacred invisible and mundane visible in Christianity. The most radical evangelicals favored the invisible and interior, whereas high-church advocates and Tractarians supported Augustine’s justification of the visible. For Augustine, the visible (or material) rendered the invisible grace of God and the Church through the visible sacrament. Clergy descended from Christ’s apostles performed that sacrament, whose materiality affirmed the authority of the physical as sacred symbol and manifestation of divine presence, engaging participants bodily and emotionally. Chief Tractarian John H. Newman argued that the Church should be understood as a nexus of both visible and invisible that interweaves the divine, sacraments, and the faithful.9 Scripture, he wrote, makes the existence of a Visible Church a “condition of the existence of the Invisible,” a means to an end (salvation) through the sacraments. The physical church is simultaneously the symbolic body of Christ, the door to salvation, a material environment for the performance of the sacraments, and a community, a standing body of the baptized faithful gathered by the clergy. The visible, maintained Newman, is as necessary as the invisible, an extension and celebration of the incarnation of the Son of God as Christ for human salvation. The body, employing its senses to apprehend and participate in church rites, is as essential for salvation as the soul that animates it.

The architectural manifestation of these views was the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century English Gothic or Pointed-style church and its decoration, an historical ideal that, for Wills, incorporated the dead among the faithful through funerary effigies. Likenesses of the exemplary departed, argued Wills, also provided vital moral lessons to the living from their own community. The striking three-dimensional recumbent statues of the clergy and nobility, their hands clasped in prayer, joined figurative floor and wall slabs commemorating the same elite to present models of the good Christian death for the living: resting in piety and humility before God and the Last Judgment.10

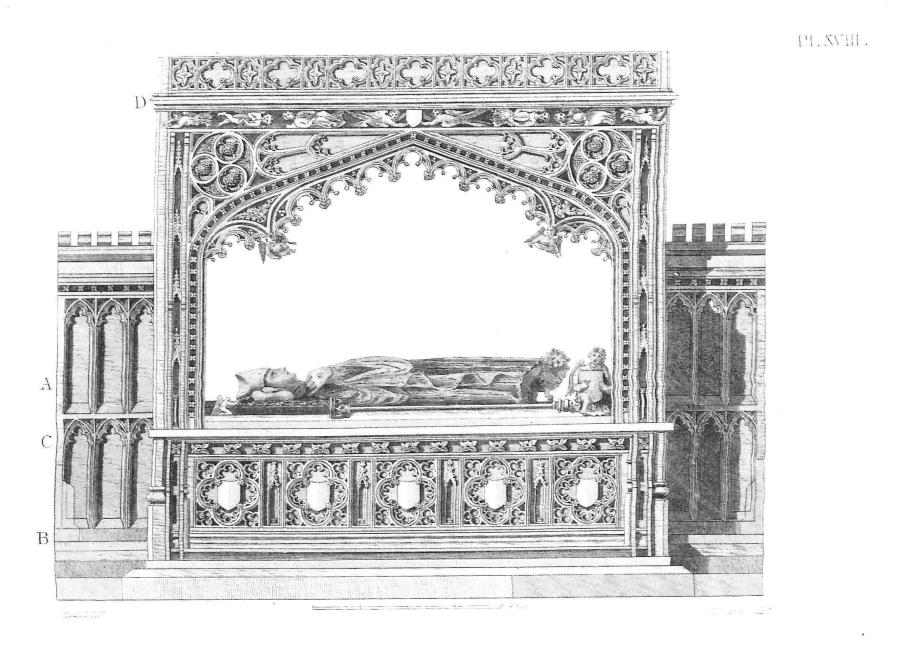

By placing a memorial to this distinguished congregant among the worshippers, the Burd canopy tomb inserted a departed member of the community among the living across time and provided a highly visible lesson in the good Christian life and death within the sanctuary. The monument thus broadly fulfills its architect’s ideals for funerary monuments within the modern church. Specifics of its design and setting, however, grew out of discussions among the architect, patron, and administration of St. Stephen’s. Mr. Burd’s widow, Eliza Howard Sims Burd (1793-1860) signed a contract with Frank Wills in October 1849, a year after her husband’s funeral and months after the vestry approved the request by St. Stephen’s rector Dr. Henry William Ducachet (1797-1865), on Mrs. Burd’s behalf, for a wall monument to her husband’s memory within the church.11 Why Mrs. Burd, the rector, and the vestry selected Wills, newly arrived in New York from Canada, is not clear, but the commission launched the project into the Anglo-American Ecclesiologist orbit. Wills had designed a canopy tomb for an English Ecclesiologist vicar’s wife (Christiana Medley) in 1842 that, together with a thirteenth-century canopy tomb for Bishop Branscombe, was the English Ecclesiologists’ top model for modern projects (Figs. 4-5).12 A comparable tomb might have seemed fitting for St. Stephen’s, a church by eminent American architect William Strickland which, after its completion in 1823, a Philadelphia critic applauded as a “highly bold and impressive” Gothic structure.13 By then Gothic idioms in church architecture were closely identified with high-churchmanship even in the United States, which further suited St. Stephen’s, founded as a high-church congregation in 1820s Philadelphia amidst new and established evangelical counterparts at a time when doctrinal differences were becoming increasingly polarized.14

- 1The unsigned canopy tomb was attributed for many years to Carl Steinhäuser, a German sculptor who executed two other signed marbles at St. Stephen’s, to be mentioned further in the text. Roger W. Moss and Sandra Tatman may be the first to return the project to Wills, in their description of “the Burd Family Monument for St. Stephen Church” in Roger W. Moss and Sandra L. Tatman, “Wills, Frank (c. 1822-1856[sic]),” hdl.handle.net/10079/06d134de-27ff-4005-b834-3357d7ca4790. For discussions of Wills’s writings, see Phoebe Stanton, The Gothic Revival & American Church Architecture: An Episode in Taste 1840-1856 (Baltimore: The John Hopkins Press, 1968), 191-93; James Patrick, “Ecclesiological Gothic in the Antebellum South,” Winterthur Portfolio 15, no. 2 (Summer 1988): 117-38, doi:10.1086/495943; and Elizabeth Ann McFarland, “The Invisible Text: Reading Between the Lines of Frank Wills’s Treatise, "Ancient English Ecclesiastical Architecture," M. A. Thesis, Cornell University, 2007. I use the term “tomb” merely to identify its generic monumental type; technically, the monument is a cenotaph (bodiless tomb), with Burd’s remains buried nearby, in the family vault along the north wall, under the children’s memorial chapel to be discussed further in the text.

- 2Frank Wills, Ancient English Ecclesiastical Architecture and Its Principles, applied to the Wants of the Church at the Present Day (New York: Stanford and Swords, 1850), 9.

- 3John Henry Hopkins, Essay on Gothic Architecture . . . (Burlington: Smith & Harrington, 1836), 14.

- 4Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 93.

- 5Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 100.

- 6Stanton, Gothic Revival, 31-211; James F. White, The Cambridge Movement: The Ecclesiologists and the Gothic Revival (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979); and Malcolm Thurlby, “Wills, Frank,” Oxford Art Online.

- 7Examples within the vast literature are Rev. John S. Stone, The Mysteries Opened . . . (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1844); Robert Bruce Mullin, Episcopal Vision/American Reality: High Church Theology and Social Thought in Evangelical America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986), 149-215; and Peter Benedict Nockles, The Oxford Movement in Context, Anglican High Churchmanship, 1760-1857 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994). For another facet of Tractarianism, see Ayla Lepine, “Fabric of Devotion: William Quillen Orchardson’s The Story of a Life and Women Religious in Victorian Britain,” Essay, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015), doi:10.22332/con.ess.2015.3.

- 8Hereafter, I will use the most common term for low-church Anglican groups, “evangelical,” from the Greek for “good news” (the Gospel).

- 9The following discussion largely paraphrases Newman’s arguments in Tract 11, published on November 11, 1833, as “The Visible Church.” (Letters I and II); see, among other places, Project Canterbury. Tracts for the Times, hdl.handle.net/10079/a2215f23-8fe2-4ced-b41f-399120fe33a4.

- 10Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 22.

- 11Henry W. Ducachet [hereafter HWD], letter dated June 18, 1849, to the vestry, transcribed in the Vestry Minutes 1849-1867 (hereafter VM); Archives, St. Stephen’s Church, Philadelphia, PA; contract dated October 13, 1849, between Frank Wills and Eliza Howard Burd [hereafter EHB]; Burd Family Papers, Special Collections, University of Delaware Library, Newark, DE, MS 379 (henceforth BFP): Ser. 3, F35. All subsequent mentions of the Burd-Wills contract derive from this source. The Burd monument appears to have been installed after 1852, date of a published guidebook that does not mention the project (R. A. Smith, Philadelphia as it is, in 1852 . . . [Philadelphia: Lindsay and Blakiston, 1852], 286-87), and by October 1860, date of a commercial stereograph (Fig 12). It is not clear if Mrs. Burd saw her husband’s memorial before her death in April 1860.

- 12For instance, James Haywood Markland, Remarks on English Churches . . . (Oxford: John Henry Parker, 1843), 71-72. Early sources reveal various spellings of Branscombe’s name. Malcolm Thurlby drew my attention to the affinities between the Branscombe tomb and those by Wills.

- 13“Description of St. Stephen’s Church, Philadelphia,” The Casket, n. s. 9 (September 1828): 409.

- 14Mullin, Episcopal Vision/American Reality, 76; Deborah Mathias Gough, Christ Church, Philadelphia: The Nation’s Church in a Changing City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1995), 211-12.

Yet a Gothic Revival canopy tomb was not the only elaborate Ecclesiologist design available for such a church. Months before, Mrs. Burd and church authorities chose a radically different plan, by Wills’s Ecclesiologist rival, architect Richard Upjohn, for a memorial to three of Mrs. Burd’s children, as specified in her husband’s will. Upjohn’s proposal was more ambitious and involved a different format: a side chapel to feature a freestanding multi-figural group commemorating the children, a separate commission given to German sculptor Carl Steinhäuser (Fig. 6). The small addition was to project into the churchyard on the church’s north side, to surmount a new burial vault for the Burd family’s gathered remains. Furthermore, the sculpture featured in each monument was identified with a contemporary artistic movement that has yet to be studied in relation to the Ecclesiologist architectural reform, Nazarene painting. These dissimilar architectural plans for the Burd family at St. Stephen’s reveal the range of Ecclesiological design while simultaneously demonstrating, in their sculptural centerpieces, reformers’ efforts to incorporate kindred activity in religious art elsewhere.1

- 1I will briefly discuss the effigy’s perceived affinities with the work of the Nazarenes, a German circle of painters in Rome, further in the text. An early study of Steinhäuser’s links to the group while in Rome is Dagmar Kaiser-Strohmann, Theodor Wilhelm Achtermann (1799-1824) und Carl Johann Steinhäuser (1813-1879): Ein Beitrag zu Problemen des Nazarenischen in der deutschen Skulptur des 19. Jahrhunderts (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lanb, 1985). I am preparing an integrated study of the Burd projects for publication.

The church administration may have been responsible for placing the canopy tomb at the church entrance, the site specified in the contract. Mrs. Burd, through Dr. Ducachet, had first proposed to the vestry that it be installed on the nave’s south wall to face the children’s memorial and family vault to the north.1 Like most Episcopal memorials of those years, which sought Christian humility even in tributes to exemplary individuals, both Burd projects avoided the traditional location for monuments in honor of important congregants: near the altar, locus of divine grace. Siting Mr. Burd’s canopy tomb at the church entrance on the west wall offered distinct alternative advantages. It prevented the wall monument—specified as to protrude from the structural wall rather than to recede into it, as was typical—from crowding the small, pew-filled interior along its length. That setting also situated Mr. Burd’s memorial closer to his children’s chapel and the family vault (Fig. 3). Furthermore, in so doing it placed the commanding monument at the church entry, becoming the first element congregants met if they turned north at the door.

Wills engaged a collaborator for the project, described in the contract as “Mr. Brown, the sculptor of New York,” who was to execute a six-foot recumbent figure of Mr. Burd seen in profile. Though unsigned, “Mr. Brown’s” statue can be attributed to American sculptor Henry Kirke Brown (1814-1886), whose correspondence of the period discusses the project.2 Recently back from years in Italy, Brown was an emerging notable with a powerful champion (the Episcopal Bishop of Pennsylvania Alonzo Potter); an effective professional network; a rising professional reputation; and commissions in many sculptural categories.3 Several additional factors may have appealed to a patron of an American church monument like Mrs. Burd and the administration of St. Stephen’s. At the time of the Burd project, Brown had intensified his declared mission to forge an authentic modern American art that, for him, included Christian subjects as part of American culture and its soul.4 The sculptor himself was also reportedly devout and closely linked his work to his own Christian background.5 During the 1840s he produced a number of religious subjects and allegorical sculpture for tombs, although nothing like his recumbent figure of Burd for the canopy tomb at St. Stephen’s, which also deployed his established skills as a portraitist.6

Mrs. Burd’s request to place family memorials within the church was apparently unusual for St. Stephen’s in 1849; at that point the twenty-six year-old congregation had few such, if any, to parishioners inside the sanctuary.7 The Burds easily met the traditional qualifications for such commemoration since both had provided exceptional service to the church. As the extraordinary scale of the interior memorials suggests, however, the couple also came from and embodied privilege. Both were white, Protestant, affluent, prominent, well-traveled members of families that had counted among the leaders and elite of Pennsylvania since the colonial period.8 Edward Shippen Burd, a successful entrepreneur and investor, contributed to southeast Pennsylvania’s rapid modernization through the 1840s and amassed considerable wealth on his own. Nonetheless, little about the couple might have foretold such an ambitious artistic undertaking as the memorials. Rather than designing their own home, they lived grandly in inherited or purchased properties.9 They were visible at cultural events but neither seems to have been a major art patron. Mrs. Burd’s watercolor miniatures, which were admired enough for her inclusion in modern biographies of artists, provide the rare hint of any artistic interests.10

According to George Sidney Fisher, one of Philadelphia’s most familiar observers who saw the Burds regularly, the couple was extravagant by their class standards in Philadelphia that condemned ostentation, even in funerary mode. Fisher, a member of that elite who repeatedly expressed a bias against conspicuous wealth, claimed that the 1844 funeral for the Burds’ twenty-five-year-old daughter Margaret typified their love of display.11 He disparagingly noted six pallbearers, a long line of private carriages for the procession between the house and the church only three blocks away, and a daytime church service with blacked-out windows and interior lit by funerary lamps.12 Even the press in distant regions derided Mrs. Burd for the “folly” of the amount of gold on her coffin—including solid gold screws and handles—visible when she was buried with considerable pomp.13 Still, early family funerary projects were not as elaborate or innovative as the two Mrs. Burd commissioned for her husband and children. For instance, there are no known church memorials to their families at their former congregation, Philadelphia’s historic Christ Church. Markers for family burials in Christ Church’s churchyards were large but typical: flat, horizontal tablets for Sims relations and a chest (or high) tomb for Mr. Burd’s mother and sister.

The extraordinary church memorials commissioned by Mrs. Burd nonetheless do reflect the couple’s most often-mentioned priorities, their extended family and the Episcopal Church. They deeply grieved the early death of their eight children, an exceptional loss even for a period famous for high child mortality at all socio-economic levels. Their respective birth families were active in the Episcopal Church during its transition in Philadelphia into a semi-independent branch of the Anglican Church, a restructuring triggered by the United States’ separation from England in the 1780s that severed church and state in the new republic.14 Both families belonged to Christ Church, famous as the birthplace of the Episcopal Church, but the young couple left to help found St. Stephen’s, where Mr. Burd served repeatedly on the vestry from its inception.15 Mrs. Burd grew up in the highest Episcopal circles. A family intimate, Rev. Dr. William White, became the first bishop of the Episcopal diocese of Pennsylvania, with its seat at Christ Church where he was rector, as well as presiding (senior) bishop of the new American denomination who codified its doctrines and governance. Mrs. Burd was especially close to St. Stephen’s second rector, Dr. Ducachet, and his wife. For the years following her husband’s demise, when she withdrew into relative seclusion, Eliza Burd was the congregation’s most consistent and generous donor, culminating in a famous asylum and school for white, legitimate orphaned girls (preferably daughters of Episcopal clergy) that she founded and endowed at her death, to be administered by St. Stephen’s.16

Virtually unknown today, the Burd memorial struck American historian Thompson Westcott in 1875 as “the finest canopied tomb in this country.”17 The marble holds a special place in the history of American funerary arts, as possibly the only example in the United States of this architectural and sculptural ensemble to be returned to its traditional setting, a church.18 In contrast, the first American versions, dating only a few years before the Burd tomb, were neoclassical variants designed for the new garden cemeteries. Introduced in the 1830s as adaptations of France’s innovative public urban cemeteries, which first opened in 1804, garden cemeteries sat outside city walls to provide healthier, picturesque burial grounds free of church control.19 The earliest known American canopy tomb appeared in the first garden cemetery in the United States, Boston’s Mount Auburn, less than a decade after the cemetery’s founding in 1831: a ca. 1840 “shrine” to four-year-old Emily Binney, with architecture by stonecutter Alpheus Cary and a recumbent effigy by sculptor Henry Dexter.20 Dexter and Cary may have modeled the Binney tomb after a specific, popular Gothic-style monument: the assemblage of medieval and new fragments dedicated to the tragic twelfth-century couple Héloïse and Abélard, located in the largest and most famous of Paris’s new cemeteries, Père-Lachaise.21 In the elegiac setting of the new American garden cemetery, the shrine in Doric mode honoring the simplicity and innocence of the dead child, rendered as a pathos-laden, life-size recumbent effigy, struck a congenial emotional and psychological chord. Though soon badly eroded and today known only through prints, the Binney tomb was an instant critical and public success, inspiring many others across the nation—many without the Binney tomb’s architectural frame. Another famous memorial to a child, Alfred Miller, in Philadelphia’s first garden cemetery, Laurel Hill (founded in 1836), is one of the earliest canopy tombs to still survive, though it is now also eroded (Fig. 7). Designed by St. Stephen’s architect William Strickland and executed between 1840 and 1844, with a marble effigy by German sculptor Ferdinand Pettrich, the monument shelters the child sleeping on his side like a slumbering infant Cupid, a celebrated classical type.22

- 1HWD, letter dated June 18, 1849, to the vestry [transcribed], VM.

- 2For instance, Henry Kirke Brown, letter dated November 26, 1849, to Elizabeth [sister of his wife Lydia]; Henry Kirke Brown papers, 1836-1893, Archives of American Art, Washington, D.C. Brown’s correspondence mentions the full-size plaster model (present location unknown) but no other preliminary works are recorded.

- 3Alonzo Potter, undated letter to HWD, BFP, Ser. 3, F34; Octavia Hughes, “The Early Work and Development of Henry Kirke Brown,” M.A. Thesis, Columbia University, 1960, 13-16, figs. 4-5. Karen Lemmey made this source available to me. For discussion of Brown and his work, see N [Nehemiah]. Cleaveland, “Henry Kirke Brown,” Sartain’s Union Magazine of Literature and Art 8, no. 2 (February 1851): 135-38; Wayne Craven, “Henry Kirke Brown in Italy, 1842-1846,” The American Art Journal 1, no. 1 (Spring 1969): 65-77, doi:10.2307/1593855; Craven, “Henry Kirke Brown: His Search for an American Art in the 1840s,” The American Art Journal 4, no. 2 (November 1972): 44-58, doi:10.2307/1593932; Karen Lemmey, “Henry Kirke Brown and the Development of American Public Sculpture in New York City, 1846-1876,” Ph.D. dissertation, City University of New York, 2005.

- 4Craven, “American Art,” 48-49.

- 5Craven, “American Art,” 48.

- 6Among recorded examples of Brown’s religious subjects, most of which are unlocated, are St. John Preaching for Troy, New York; a known religious funerary project is his bronze Angel of the Resurrection (ca. 1850, Hogg tomb, Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh). Brown also competed unsuccessfully for the Burd children’s memorial. See “Brown’s Studio,” Bulletin of the American Art-Union 2, no. 3 (August 1849): 18. Karen Lemmey directed me to this text. An example of Brown’s earlier portraiture in marble is his bust of Asher B. Durand (1847, National Academy of Design, New York).

- 7Fig. 11 shows a wall plaque on the north wall at left that cannot be identified among surviving examples.

- 8John Frederick Lewis, The History of an Old Family Land Title . . . (Philadelphia: Patterson & White, 1934), 113-18; and Harrold E. Gillingham, “Notes on the Burds of Ormiston, Scotland and Philadelphia,” Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Publications 13 (1941): 173-92.

- 9The Burds bought their famous, elaborately furnished townhouse, designed by prominent Philadelphia architect Benjamin Latrobe, from Mrs. Burd’s uncle and guardian Joseph Sims. Mr. Burd inherited their summer home Ormiston (now one of the historic houses in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park) from his father, who purchased it.

- 10For various references, see Anita Jacobsen, ed., Jacobsen’s Biographical Index of American Arts . . . (Carrollton, TX: AJ Publications, 2002) 1, Book 1: 475.

- 11A Philadelphia Perspective. The Diary of Sidney George Fisher . . . Nicholas B. Wainwright, ed. (Philadelphia: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1967), 164-65. According to Fisher, Margaret died of tuberculosis.

- 12Though Fisher omitted this fact, after the funeral, the procession transported Margaret’s coffin for interment in one of Christ Church’s two burial grounds, one about six blocks east of St. Stephen’s; the other at Christ Church itself, about eight blocks east of the church.

- 13“Things in General,” New Hampshire Statesman (London) (April 21, 1860): n. p.

- 14Among the many studies of the history of the Episcopal Church: James Thayer Addison, The Episcopal Church in the United States 1789-1831 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1951); and David R. Contosta, ed., This Far by Faith: Tradition and Change in the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2012).

- 15Gough, Christ Church; Rev. Washington B. Erben, “The Protestant Episcopal Church,” in J. Thomas Scharf and Thompson Westcott, History of Philadelphia 1609-1884, 3 vols. (Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co., 1884), 2: 1351.

- 16“Editors’ Table: A True Benefactress. Burd Orphan Asylum of St. Stephen’s Church, Philadelphia,” Godey’s Lady’s Book and Magazine 64 (March 1862): 295. Mrs. Burd started the boarding school in buildings near her townhouse before she bequeathed funds to build a celebrated complex just outside Philadelphia (since demolished). Though she dedicated the asylum to her husband, it became effectively a memorial to her; she is otherwise unacknowledged within the church itself, unlike a later woman patron, Miss Anna J. Magee.

- 17Thompson Westcott, The Official Guide Book to Philadelphia: A New Handbook for Strangers and Citizens . . . (Philadelphia: Porter and Coates, 1875), 288. I learned of the Burd projects through William H. Gerdts’s brief account of them in his essay, “American Memorial Sculpture and the Protestant Cemetery in Rome,” in Irma B. Jaffe, ed., The Italian Presence in American Art 1860-1920 (New York: Fordham University Press, 1992), 133.

- 18Gothic-style effigy tombs without architectural frames are more ubiquitous in American nineteenth-century churches or chapels. Among early examples are Edward V. Valentine’s celebrated effigy tomb for Robert E. Lee (1871-1883; Lee Chapel, Washington and Lee University, Lexington, VA); William Wetmore Story’s effigy tomb for university founder Ezra Cornell (1885, Sage Chapel, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY); and that by an unknown for the Bishop of New York Horatio Potter (c. 1921; Cathedral of St. John the Divine, New York, NY, which Bishop Potter founded).

- 19Richard A. Etlin, The Architecture of Death: The Transformation of the Cemetery in Eighteenth-Century Paris (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1984).

- 20Blanche Linden-Ward, Silent City on a Hill: Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1989); Joy S. Kasson, Marble Queens and Captives: Women in Nineteenth-Century American Sculpture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990), 109-13, fig. 34; and Elise Madeleine Ciregna, “Museum in the Garden: Mount Auburn Cemetery and American Sculpture, 1840-1860,” Markers 21 (2004): 111-14. I follow the redating of the Binney tomb to 1840 from 1842 in Ciregna, “Museum in the Garden,” 112.

- 21Etlin, Architecture of Death, 268, 344; fig. 252. This monument was designed by archaeologist Alexandre Lenoir for the Elysian gardens, a prototype for the later municipal cemeteries, around his Museum of French Monuments in central Paris. When the complex was dismantled in 1816, the monument to Héloïse and Abélard was among several in the gardens to be transferred to Père-Lachaise. Following its style and setting, Gothic Revival cemetery canopy tombs in the United States are Karl Muller’s celebrated monument to John Matthews (ca. 1870, Green-Wood Cemetery, Brooklyn, New York) and the tomb of Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnson, with an effigy by Elisabet Ney (1905, Texas State Cemetery, Austin).

- 22Guide to Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia: Laurel Hill Cemetery, 1844), 38; R. A. Smith, Smith’s Illustrated Guide To and Through Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia: W. P. Hazard, 1852), 112.

Despite Wills’s praise of the canopy tomb for Edward Shippen Burd, his description of the monument itself is curiously uninformative. The passage merely notes that the monument consists of a “richly panneled Tomb, on which lies the effigy of the departed” and a “richly wrought canopy over the tomb flanked by figures of Faith and Hope.”42 The monument likewise lacks an epitaph or any other form of explanation for the extravagant tribute within the church, of the sort that often appears on Episcopal church memorials. Wills’s text, however, describes Burd as a benefactor of the American church where the memorial would be placed, tacitly giving us the subject’s munificence and piety as reasons for the scale, prominence, and program of the enterprise. Wills also claimed he designed the monument to honor the spirit of “ancient, religious art.”43 Yet his discussion tells us nothing about the meaning of the architecture and its nonfigurative decoration.

Through the architectural type (canopy effigy tomb) and setting, Wills’s memorial for Edward Shippen Burd recruits an elaborate medieval church monument to similarly claim the intimate bond between this modern departed faithful and his religion. Towards this end, the densely detailed architecture and simple sculpture of the memorial complement one another. As Wills described it, Mr. Burd’s effigy is flanked on the canopy corner tabernacles by sculptural personifications of theological virtues, Faith and Hope. The horizontality of the figure formally echoes the linear arrangement of the Christological emblems across the canopy. Christograms flank emblems of the Passion.1 The alignment of these symbols with the effigy, as a form of dialog or embrace, may signify both Burd’s faith and Christ’s blessing. The cherubs, whose heads appear on the arched canopy sheltering the effigy, reinforce the sense of divine favor. Burd’s dynastic guise and personal biographical data become absorbed into the overall Christian message. Even the family motto, employing as it does the first-person singular (“spes mea [my hope]”), becomes less a display of dynastic pride than an individual affirmation of faith in the cross.

When compared to Wills’s Medley tomb of 1842 and the thirteenth-century monument to Bishop Branscombe, the Burd memorial reveals how it relates to each of the earlier projects, and how it does not.2 In its overall design and architecture, the Burd canopy tomb is nearly the mirror image of Wills’s Medley memorial (Fig. 4) and kin to the earlier monument to Bishop Branscombe (Fig. 5). All three share distinctive horizontal architectural frames and both the Medley and Burd tombs appear to be variants of an unsigned elevation plan justifiably attributed to Wills (Fig. 8).3 The Medley tomb closely follows the elevation except for the overall ornament. The Burd tomb, in contrast, reverses the order of the Christological emblems in the elevation and adds the heraldic devices of the Burd family in Scotland: its fleur de lys in the cornice and the two panels of the chest tomb, with the full coat of arms on the screen behind the effigy. The motto “In croce spes mea [my hope is in the cross]” also derives from Mr. Burd’s Scottish forebears.

- 42Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 100.

- 43Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 100.

- 1The Passion is the cycle of Christ’s life and death that encapsulates Christian belief in Christ’s birth for self-sacrifice (through trial, torture, and crucifixion) to provide entry into Heaven for a humanity tainted by original sin. IHS is a monogram of the Greek spelling of Jesus’ name, overlaid by the cross.

- 2Their materials and surface treatment emphasize differences not visible in the engraving of the Branscombe tomb (Fig. 5). Where the Burd effigy tomb was executed in white marble and the Medley tomb in gray stone, the Branscombe tomb, also in stone, was given a gilt polychrome surface.

- 3Like the two Wills tombs, the Branscombe tomb bears a decorated cornice that does not appear in the print. This elevation is likely the one in the “Public Archives of Canada” identified as for the Medley tomb by Douglas Richardson in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, 8: s. v. “Wills, Frank;” perma.cc/QL8U-78JS

Brown’s effigy of Burd follows Gothic precedents in its supine position and forward orientation. Its simple jewel-necked garb could be the masculine counterpart to Christiana Medley’s veiled medievalizing garb. The iconography of the sculpture otherwise departs markedly from that of Mrs. Medley and of Bishop Branscombe. Unlike the other two, the Burd statue bears no attributes of status or emblematic animals; such symbols appear solely on Wills’s architectural frame. The figure’s relaxed posture, with crossed hands and feet, also distinguishes it from the Medley and Branscombe effigies with their traditional poses, praying hands, and legs extended. Indeed, Brown’s effigy’s positioning mirrors Christian Daniel Rauch’s celebrated tomb effigy of the sleeping Prussian Queen Louise (ca. 1810-14), which updates, with singularly charming informality, the crossed-legs pose of sleep or death evidenced by many classical mythological or allegorical figures (Fig. 9).

The head in Brown’s effigy broadly resembles a known portrait of Edward Shippen Burd in his maturity (Figs. 2,10), conveying a strong sense of human presence within equally strong artistic controls. The handling of the marble softens physiognomic fact and harmonizes features and hair in rhythmic volumes and lines that continue in the drape on the body. Such a subtle combination of modern features, gently naturalistic rendering, and historical references places Brown’s unfamiliar figure of Burd among celebrated effigies for European church tombs from its own decades. All similarly develop a sculpture based on a Gothic prototype that iconographically and stylistically falls midway between Gothic formality and extreme modern naturalism. The modernity and naturalism that distance Brown’s figure of Burd from the very Gothic Medley effigy instead recall Richard Westmacott’s more pliant Crusader-like draped figure of Christopher Jeaffreson (late 1820s, Dullingham, Cambridgeshire).1 The same qualities relate the portrait statue of Burd to most of the effigy tombs commissioned by the duc d’Orléans (later King Louis-Philippe of the French) for his family, beginning with that for his brother, the Duc de Montpensier, at Westminster Abbey (1829-30).2 As a canopy tomb effigy, however, Brown’s figure of Burd adheres more to the Gothic model than to Vincenzo Vela’s highly realistic monument for the Countess d’Adda (1851-53, Cappella Vela, Villa Borromeo d’Adda, Arcona). Vela’s monument to the Countess transforms the canopy tomb into a startlingly modern deathbed scene; he places the dying woman in a spectacular canopied bed within the space of the family chapel, the heavens opening to receive her.3

- 1Nicholas Penny, Church Monuments in Romantic England (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1977), 121, fig. 91.

- 2Suzanne Glover Lindsay, Funerary Arts and Tomb Cult: Living with the Dead in France, 1750-1870 (Farnham: Ashgate, 2012), 119-50 (identical pagination in the Routledge 2016 paperback edition).

- 3Nancy Jane Scott, “Vincenzo Vela (1820-91),” Ph. D. dissertation, New York University, 1978, 147-52.

For Frank Wills, these blended formal qualities identified Brown’s effigy of Burd with yet another highly regarded artistic community in Europe. The figure’s dignity and naturalism, united to the “purity of art,” claimed Wills, were signs of Brown’s successful study of the work of Johann Friedrich Overbeck (1789-1869).50 In the early nineteenth century, Overbeck was the leader of a circle of mostly German painters in Rome informally called Nazarenes for piety, long hair, and “biblical” dress that invoked images of Jesus of Nazareth. These artists sought to revive true spirituality in modern Christian art using medieval models rather than the classical ones that had dominated from the High Renaissance onward. In the mid-nineteenth century, Overbeck himself remained a much-acclaimed exemplar of the modern Christian artist and his work an influential standard for modern Christian art in England and the United States.51 While in Rome, Brown had openly admired Overbeck’s paintings and considered their lessons for his own pursuits.1 Wills’s association of Brown’s sculpture of Burd with Overbeck’s paintings and prints suggests the architect believed Brown had finally rejected the “pagan” antique that many in the 1830s and 1840s saw as compromising Christian sculpture after the Middle Ages.2 The simple robe that Brown gave his effigy may be an iconographic motif borrowed from Overbeck’s paintings to signal the sculpture’s adherence to Nazarene principles.3

Wills reports Brown’s characterization of Mr. Burd in the effigy as rendered “sleeping not dead, waiting in hope of heaven” (emphasis in original), a description revealing of Brown’s perception of the monument’s funerary function.55 This familiar description of death—dating to antiquity but also found throughout Scripture—is more complex and vexed than it seems. In early passages of his book, Wills presented the basic Christian belief that when the soul leaves the body at death, the body then sleeps and disintegrates in the tomb until the two are reunited at the Resurrection.4 Anglicans and Catholics both embraced this concept of the body slumbering at death, suggested in the recumbent pose of the effigies of Mrs. Medley and Bishop Branscombe (Figs. 4-5). Their effigies become idealized images of their buried bodies, symbolically invoked by the chest tombs underneath; Brown’s figure of Burd may follow suit.

Although Roman Catholics and Anglicans agree on what happens to the body after death, a vast gulf emerges in the two Churches’ divergent beliefs about the post-mortem destination of the soul.5 Simply put, Catholic souls, like that of Bishop Branscombe, went to Purgatory (an ill-defined and much-debated posthumous state or zone for most mortals) as penance for remaining sins. The only souls to avoid time in Purgatory were the worst sinners, who went directly to Hell, and the saints, who went directly to Heaven. The living could relieve the suffering of a soul in Purgatory through papal pardons, indulgences (the lessening of posthumous punishment with lifetime actions prescribed and granted by the Church), masses, and prayers. Adherents to the Reformation and subsequent evangelical Anglo-Episcopalians excoriated the practice of intervention by the living on behalf of the dead as usurious, denying direct accountability to God, and rejecting Jesus’ loving sacrifice on their behalf.

The evangelicals’ bitter hostility to the doctrine of Purgatory and intercession by the living encouraged a binary vision of the afterlife that eclipsed other options. For them, the soul of the departed went directly to its permanent destination: the wicked to Hell and the blessed to Heaven, where each awaited reunion with its regenerated body at the Resurrection. Ambiguities in the Scriptures otherwise led either to dismissing the question of an intermediate afterlife as part of the great Christian mystery—or to prolonged debate. One alternative that surfaced repeatedly, fomenting strong resistance, attempted to answer the question: if there is no Purgatory and the direct Heaven-Hell option seems implausible, where does the soul go at death, and in what state of awareness if, as Scripture indicates, it is awakened at the Last Trump for the Last Judgment and assignment to eternal fate?6 Often arguing against sects that believed the soul died or slept insensate until Judgment Day, divines including Reformer John Calvin (Psychopannychia, 1534) and seventeenth-century Anglican moderates like Bishop Jeremy Taylor (Rules and Exercises of Holy Dying, 1651) took another route. They contended that Scripture indeed supported the view that the soul moved to rest, conscious, in a temporary place of bliss for the blessed and of misery for the damned. Their arguments sank into obscurity, however, partly because evangelical Anglicans felt this concept still evoked Roman Catholic Purgatory.

Nevertheless the doctrine of the intermediate state of the conscious resting soul surfaced again in Anglo-Episcopal circles in the nineteenth century. One of the most detailed and thoughtful versions came from the high-church American theologian and Episcopal bishop John Henry Hobart (1775-1830) who was well known in Philadelphia, where he was born and raised, and at St. Stephen’s, where he was friend and mentor to the first rector and delivered the consecration sermon in 1823 to publicly advertise the congregation’s high-church position.7 First presented in a sermon at the memorial service for his predecessor as Bishop of New York in 1816, Hobart’s proposal was published repeatedly thereafter with an extensive scholarly apparatus.8 Without rebutting the dominant Anglican version, Hobart claimed his was the first systematic Anglo-Episcopal treatise on the afterlife, drawing on sources from earliest time through a range of modern British Protestant divines, from Presbyterians to the Anglican Bishop Taylor.

Hobart’s arguments provided a middle course through many of the debated issues while emphatically distinguishing his concept of an intermediate state from Roman Catholic Purgatory. Hobart contended that Anglo-Episcopalians’ chosen lives after baptism and confirmation, when they acted (or not) upon promises made at those rites to pursue a life devoted to Christ’s teachings, determined their afterlife. Upon the body’s demise, all souls traveled to an invisible zone divided into the dwelling of those who had lived in sin, where they experienced a foretaste of Hell, and Paradise (often called the Bosom of Abraham), the home of the faithful who enjoyed a foretaste of Heaven in the custody of Christ and the angels alongside the Church fathers, saints, and infinite worthies.

Although Scripture described this state for both body and soul as sleep, Hobart argued the soul was necessarily aware, merely resting awake, able, unlike the body, to experience its postmortem condition. The Last Trump eventually reunited everyone with their regenerated bodies to send them to their corresponding destinies at the Last Judgment. Later—and wider—support for this concept can be seen in at least one Anglican text dating close to the Burd project, an 1845 book on Anglican prayers for the dead that affirms an intermediate afterlife of rest for the blessed who are still helped by requests to God, sole authority in such matters, for their repose before the Resurrection.9

Although founded as a Hobartian high-church congregation, St. Stephen’s position vis-à-vis this doctrine at mid-century is difficult to fix. Dr. Ducachet’s sermons were apparently never published and no recorded interpretations of the Burd memorial by congregants have emerged. Yet there are signs of the doctrine in parish documents relating to Mrs. Burd. Dr. Ducachet used the language of the aware, resting soul in a handwritten note on her burial in the parish register: “Her body lies in the crypt beneath the monument to her three children—her soul rests in hopes!"10 Moreover, iconographic cues link Brown’s effigy of Burd to Hobart’s version of the resting virtuous soul. Hobart’s physiognomic index for the conscious soul enjoying its intermediate state while it anticipates the full bliss of Heaven is the embodied spirit in repose, with eyes open to savor the pleasures of Paradise. Similarly, the figure of Burd is unusually relaxed and the eyes are slit, focused vaguely forward, unlike Mrs. Medley’s closed eyes, which suggest the effigy represents the young woman’s body sleeping in death as she awaits the Last Judgment.

The facial difference between the two figures reinforces the prospect of reading Brown’s statue in Hobartian terms as Burd’s embodied soul, resting in contented enjoyment of Paradise while awaiting reunion with his improved, resurrected body at the Last Trump for entry into Heaven. If so, the Burd effigy provides a radically different image of the soul after death from typical ones on Anglican funerary monuments. As Nicholas Penny has argued, Anglican examples usually represent the separation of body and soul at death, the soul rising heavenward, alone or accompanied by angels, as in John Flaxman’s monument to Agnes Cromwell (ca. 1798-1800, Chichester Cathedral).11 Penny defended these as images of the ascending soul, rather than of the resurrected body, by pointing to Matthew Cotes Wyatt’s monument to Princess Charlotte (1817-24, St. George’s Chapel, Windsor Chapel) that represents her soul rising from her draped recumbent body.12

The alternative view of Burd’s resting figure as his soul in Paradise proposed here then inflects the interpretation of the entire ensemble. The canopy framed by cherubs, Hope and Faith, which typically serves as the body’s sanctified shrine in other Protestant monuments, instead gives architectural form to the soul’s immaterial temporary zone of bliss—an unworldly domain physically inserted into that of living congregants. The attributes of the Passion on the canopy emphasize Christ’s custody of Burd’s soul in Paradise. The signs of the Passion and various forms of family heraldry, linked by the family motto, emblematically place Burd among his forebears in Paradise who also hope for Heaven, thanks to the gift of immortality through Christ’s Passion.

During the negotiations and planning for the Burd canopy tomb in 1849, the chosen location of this self-contained memorial, representing Burd’s soul resting in Paradise, allowed the monument to fulfill one aspect of Wills’s vision for the ideal Christian church: to bring together generations of the faithful, living and dead, in shared community. As Wills proposed, St. Stephen’s structure otherwise limited the monument’s interaction with its setting, even though at its birth the church had been applauded as an American Gothic architectural gem. What in 1828 struck a Philadelphia critic as a “correct specimen of the Gothic Architecture of the middle ages” did not conform to Wills’s vision drawn from thirteenth- and fourteenth-century English pointed-style churches.13

Instead of Wills’s lengthy aisles, for the congregation’s reverential passage from the entrance to its pews in the nave, and from there to the chancel railing for Communion (a key sacrament linking the faithful to the divine), and instead of arched walls soaring heavenward to the lofty vaulted ceiling, St. Stephen’s offered Gothic ornament on the walls and flat ceiling of the wide, galleried “auditory” Protestant structure, designed to maximize the number of congregants who, clustered close to the chancel, could pray together and hear the Gospel delivered at the pulpit, a plan adopted in many Episcopal churches through the 1820s that drew on designs by seventeenth-century English architect Christopher Wren and eighteenth-century Scottish architect James Gibbs.14 All attention focused forward with little value given to symbolic physical progression throughout the space or to the contributing symbolism of all walls and zones. As an Ecclesiologist reformer, Wills cared about the integrated, three-dimensional whole, yet was remarkably tactful about the shortcomings of existing structures in his published arguments. His book criticizes poor or alternative design without mentioning specific culprits, evokes an ideal with various examples, real and imagined, and applauds executed elements as models for inclusion in his ideal church (windows, towers, and monuments) without regard to their actual setting.15

As the Burd canopy tomb was executed and installed, St. Stephen’s underwent an aesthetic, ritual, and symbolic transformation intended to bring it closer to Wills’s published ideal. In 1850, Mrs. Burd proposed to make St. Stephen’s “conform to ancient ecclesiastical usage” at her expense.16 By 1853, under Richard Upjohn’s guidance, the church administration elevated the chancel by three steps to further distinguish it from the nave, added a reredos, renovated the pulpit, updated the colored-glass windows, and installed a nine-bell chime in the tower. Contemporary stereographs and a painting suggest what the interior looked like by the 1860s, before new radical changes beginning in the 1870s took the church in other directions. The painting (Fig. 11) represents St. Stephen’s interior with medium-value gray-green walls accented by light-colored gallery railings, colonnettes, and ceiling. The canvas suggests a space whose muted atmosphere emphasized the contrasting light and hue from colored-glass windows. One unidentified critic, writing soon after the modifications, applauded the new windows which “glowed on a sunny morning like tinted lamps,” creating a “dim religious light, eminently in harmony with all around."17 This account may register an observed effect, but the rhetoric virtually paraphrases Wills’s published description of light within the historical ideal that he sought in modern churches: “The glowing sun streams through the pictured windows, bathing the whole edifice in a flood of the richest ‘dim, religious light.’”18

- 50Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 100.

- 51Cordula Grewe, Painting the Sacred in the Age of Romanticism (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009), and The Nazarenes: Romantic Avant-Garde and the Art of the Concept (University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2015). A subject that invites deeper study, admiration for Overbeck and the Nazarenes as models for modern religious art (mostly painting) permeates the writings on the reform of modern Christian art in the United States and England led by architect Augustus W. R. Pugin. See his Contrasts, or a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Middle Ages and Corresponding Buildings of the Present Day: Showing the Present Decay of Taste, 2nd ed. (Edinburgh: John Grant, 1898), 18; first published in 1836.

- 1Craven, “Brown in Italy,” 69, 71.

- 2Just Mathias Thiele, The Life of Thorvaldsen, collated from the Danish by Rev. M. R. Barnard (London: Chapman and Hall, 1865), 139-239; David Bindman, Warm Flesh, Cold Marble: Canova, Thorvaldsen and Their Critics (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014), 46-50, 155-56. Sculpture produced during these years in Rome, under the continuing influence of Canova and Thorvaldsen after their death, differs strikingly from French sculpture of the same period which offers various neo-medieval and neo-Renaissance approaches acclaimed by French progressives as Romantic. A seminal early study of this body of French sculpture is Luc-Benoist, La Sculpture romantique, Isabelle Leroy-Jay Lemaistre ed. (Paris: Gallimard, 1994; first published 1928).

- 3A good example of this apparel is in Overbeck’s group portrait of the Lukasbund (the given name of the brotherhood of German painters forging the new Christian art who were later nicknamed Nazarenes) within his Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (1824, oil on canvas, destroyed), a key manifesto painting that adapted Fra Angelico’s Christ’s Entry into Jerusalem (1450, oil on canvas, Museo di S. Marco, Florence). Since destroyed, Overbeck’s painting became well known through lithographs of it. See Grewe, Painting the Sacred, figs. 1.1-2. Overbeck’s own effigy, by Karl Hoffman for his 1871 niche tomb in S. Bernardo alle Terme, Rome, offers some of the same formal qualities as Brown’s figure of Edward Shippen Burd despite a more elaborate robe.

- 55Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 100.

- 4The Resurrection refers to the raising of the souls and restored bodies of the dead at the end of time for Final Judgment and ascription to Heaven or Hell, an event that the apostle Paul described as heralded by the Last or Final Trumpet (poetically described in English as “Trump”) See 1 Corinthians 15:52

- 5Penny, Church Monuments, 90-97, 108-18; Paul Binski, Medieval Death: Ritual and Representation (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1996), 93-94; Peter Marshall, Beliefs and the Dead in Reformation England (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003), especially 47-231, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198207733.001.0001; and Peter Sherlock, Monuments and Memory in Early Modern England (Farnham: Ashgate, 2008), especially 41-127.

- 6Briefly mentioned in Marshall, Beliefs, 193-94, but developed through the seventeenth century in William M. Spellman, “Almost Final Things: Jeremy Taylor and the Dilemma of the Anglican View of the Dead Awaiting Resurrection,” Anglican and Episcopal History 63, no. 1 (March 1994): 35-50.

- 7The Washington Theological Repertory and Churchman’s Guide 4 (May 1823): 312; Alfred W. Price, The Rich Heritage of St. Stephen’s: Some Highlights of History (Philadelphia: St. Stephen’s, 1948), 5, 11-12.

- 8John Henry Hobart, A Funeral Address Delivered at the Interment of the Right Rev. Benjamin Moore . . . [with] an Appendix on the Place of Departed Spirits, and the Descent of Christ into Hell (New York: George Long, 1816).

- 9W. F. W., “Preface,” Prayers for the Dead, for the Use of Members of the Church of England . . . (London: James Toovey, 1845), v-xxxiv. The Church of England neither officially condoned nor condemned such prayers then but evangelists abhorred them as Roman Catholic intercessions that denied God’s direct authority. Newman’s Tract 90 of 1841 claims various early doctrines propose a judgmental fire, a painless purgation, or progressive sanctification for even the blessed after death. Newman’s arguments nonetheless so offended evangelists, as support for the Roman Catholic Purgatory, that he was “hounded” out of Oxford. See Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church (London: Adam & Charles Black, 1966), 1:184.

- 10Annotation signed “H. W. Ducachet,” April 10 [1860], Parish register 1823-1865, Archives, St. Stephen’s Church.

- 11Penny, Church Monuments, 91-97, fig. 70; other examples of tomb imagery of the ascending soul appear in figs. 68-73. This vision of the virtuous soul rising from the body to Heaven at death can be found in contemporary Anglican hymns often sung at funerals, such as one titled “How blest the righteous when he dies!,” inspired by a popular poem by Anna Laetitia Barbauld (1743-1825). The relevant verse is: “Life's done, as sinks the clay/Light from its load the spirit flies/How blest the righteous when he dies!”

- 12Other Anglican monuments with a relief of the spirit of the departed rising from a recumbent effigy (for instance Joseph Edwards’s monument to Charlotte White, Berechurch, Essex) represent, according to Penny, the dying woman’s vision of her imminent transition. Penny, Church Monuments, 92-93.

- 13“Description of St. Stephen’s Church.”

- 14G. W. O. Addleshaw and Frederick Etchells, The Architectural Setting of Anglican Worship (London: Faber and Faber, 1948).

- 15Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 44, 46, 49-62, 91-99.

- 16EHB, letters from June 17, 1850-December 19, 1853 to the vestry [transcribed]; VM.

- 17“St. Stephen’s Church," Illustrated News [New York, NY] 2, no. 28 (Saturday, July 9, 1853): 14.

- 18Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 21. The quoted “dim, religious light” is a topos repeatedly applied to Gothic Revival churches during the mid-nineteenth century that appears, as Wills notes (p. 59), in John Milton’s Il Penseroso (1645-46), a pastoral poem that includes the thoughtful walker’s meander through an abbey church during services.

With the structural changes to the east wall and its atmospheric nave, St. Stephen’s came closer to Wills’s vision of even the humble parish church, as a multi-faceted symbolic whole that included the dead, something American opponents like Bishop Hopkins would have condemned. As Wills described interior memorials, the Burd canopy tomb unites generations of worshippers, living and deceased, at its very entrance. Through the 1860s, there was apparently no inner vestibule, allowing the memorial to project even more forcefully from the west wall, as we see in this photograph of 1860 (Fig. 12).1 Arriving for and leaving after services, congregants contemplated this monumental representation of the path to Heaven that jutted toward them as they moved through the tight space between the entrance and pews. Children might study the monument as part of their catechism inside the church on Sunday afternoons during Lent.2

- 1The current vestibule (the result of an added decorative “screen”) reportedly replaced a wooden version in 1918. See Carl E. Grammer, Order of Service at the Presentation of Alterations and Decorations by Miss Anna J. Magee (Philadelphia: St. Stephen’s Church, 1918), n. p.; www.philadelphiastudies.files.wordpress.com.

- 2“Report of the Rev. Henry W. Ducachet . . . ” Journal of the Proceedings of the 62nd Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the State of Pennsylvania (May 19-21, 1846): 75. Lent is the liturgical period of preparation for Easter, the holiday which celebrates Christ’s resurrection after his crucifixion and burial.

The memorial’s proximity to the entrance also plays a symbolic role within the entire church. The main entrance (usually on the west wall, as at St. Stephen’s) was the canonical site of the baptismal font, the ritual form that participates in the Christian’s symbolic birth into the Church.1 Thus the canopy tomb is adjacent to the physical entrance that is also the symbolic portal to the first stage of life in Christ. Together, the tomb and font embody thresholds of life in the Church as the font finds its sequel in the canopy tomb, the material rendering of the invisible place beyond. Here, the departed faithful rests pleasurably in Christ’s custody, the promised first reward for a life of worship within St. Stephen’s. The sanctuary that extends eastward from the west wall embodies and enables that life of worship between baptism and death: the nave, domain of the lay faithful preparing for Heaven who, in their pews, hear the Gospel and Word delivered at the pulpit; who then traverse the carpeted floor to commune with God at the elevated chancel railing, the border of the domain of the “church triumphant” (Heaven on earth), with the altar as the climax of the building.2 A symbolic whole of complementary parts, where each zone and component participates in the Church and path to Heaven, including death and the departed.

Finally, the affective materiality of the Burd monument comes into play as well. Absorbed into the overall fabric, the canopy tomb lends its own weightiness and gravitational tug to that of the church. As Wills’s book maintains, the strong, heavy mass of the building’s simple walls and towers embodies the dignity and resilient strength of even a small parish church battered by the storms of life.3 Through its symbols, imagery, and weighty physicality, the funerary monument proclaims the good news of the afterlife and enhances the doctrinal strength of the entire site. Joining the vibrant power of chimes, organ, and choral music, and the visible, audible, and biokinetic sacrament performed by clergy and congregants at the chancel or font, the Burd canopy tomb forms part of the complex entity that is the Church for advocates of the visible/material. The monument places the dead among the living with a bodily force as persuasive as its doctrinal assertions, and gives eloquent material form to the promised initial bliss for the faithful who, immediately across the mortal threshold from the living, await Christianity’s highest gift, eternal life in Heaven.

- 1The site of the font at St. Stephen’s in the 1850s is problematic. According to the “Description of St. Stephen’s Church,” the original font stood where Steinhäuser’s monumental lidded font is shown in Fig. 11, near the chancel, a location favored by many Episcopal and Anglican churches so the congregation could witness baptisms during services. However Mrs. Burd donated the font on the proviso that the original one continue to be used, if desired, until a worthy mission church needed it (EHB, letter dated December 20, 1859, to the vestry [transcribed], VM). Especially if encouraged by Ecclesiologist architects, the administration of St. Stephen’s likely placed that original font (current location unknown) in the canonical site by the entrance to the south of the doors, where Mrs. Burd’s font resides today.

- 2Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 50-55; 60-62.

- 3Wills, Ecclesiastical Architecture, 61, 88.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2017.1

1. Suzanne Glover Lindsay, "The Canopy Tomb of Edward Shippen Burd," Essay, in MAVCOR Journal 1, no. 1 (2017), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2017.1

Lindsay, Suzanne Glover. "The Canopy Tomb of Edward Shippen Burd." Essay. In MAVCOR Journal 1, no. 1 (2017). doi:10.22332/mav.ess.2017.1