Beverly Lemire is Professor and Henry Marshall Tory Chair in the Department of History, Classics & Religious Studies, University of Alberta. Her work examines intersecting areas of material culture, gender, race and fashion from c.1600-1900 in British, imperial and comparative global projects. A recent volume offers a bottom up examination of early modern globalism: Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures. The Material World Remade, c. 1500-1820 (Cambridge University Press, 2018). She led a collaborative interdisciplinary team in the “Object Lives” project (2014-2018): www.objectlives.com, with a newly published collection: Object Lives and Global Histories of Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion, c. 1780-1980 (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

The concept of early modernity is shaking off its old Eurocentric connotations as historians of other regions and peoples find “common threads in the worldwide experience” of these centuries, most specifically in the “worldwide diffusion of new commodities.”1 This era is notable for more intensive and sustained interactions, including the translation of highly esteemed goods arising from Indigenous North American, African, Arabian and Asian cultures, moving to far flung world centers through the entanglement of people, goods, and political circumstance.2 Understanding these changes is better achieved through investigations outside privileged realms, including with media like tobacco and the material meanings that ensued with its travels. Studies, such as this one, open vital historical vantage points, where subaltern knowledge and agency figure in singular ways. Marcy Norton is prominent among the new generation of historians who place Indigenous American and African peoples at the center of early modern Atlantic world events.3 These histories reveal the porosity of European and Euro-colonial societies and the dependence of elite Europeans on material cultures that can be incorporated into the term Indigenous technology (whether arts, material culture, or processes of use). These materialities spread through colonial and metropolitan polities and cultures.4 Norton argues for the term “technology” as a means to encapsulate tangible media—including tobacco pipes —which also includes the wisdom, cultural, and spiritual facets of things arising from the Indigenous Americas. Directing particular attention to the myriad of “subaltern technologies” that distinguished these works, systems of knowing and doing that ultimately revised wider material worlds, Norton delivers a riposte to the historic denial of “imperial and colonial dependence” on these technologies.5 The tobacco pipe was a powerful translational tool. Its look and shape, feel and function footnote the transformational features of the early modern Atlantic world: landscapes of exchange. My focus is the multiple iterations of the pipe within the wider Atlantic basin arising from Indigenous forms, media that came to define this period, its solitary reveries and diverse sociabilities, systems of power, and deft resistances.

The history of technology originally focused on chronologies of western innovations—the term “technology” defined by Thomas Parke Hughes as part of a “human-built world.”6 More recently shifts in fields such as the history of science and technology, along with the developing field of the history of knowledge, manifest a far more capacious view of knowledge and applied knowing—itself a kind of technology.7 Simone Lässig, a social and cultural historian of Central Europe, observes:

Only in the last decade or two have scholars developed a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between knowledge and power that centers on the complexities and ambiguities of knowledge production and circulation in contexts of asymmetrical power relationships. This new understanding is reflected in the growing interest in topics such as subversive knowledge practices, the preservation of traditional knowledge, and the incorporation of subaltern knowledge within hegemonic knowledge.8

These subject areas lend themselves to the overarching rubric of subaltern technology, taking explicit account of the materiality through which knowledge was expressed, including by Indigenous populations, non-elite women and men, and later colonizing and colonized peoples of the Atlantic world. Norton notes that: “Deploying the term [subaltern technology] in its more capacious sense assists in moving away from cultural-evolutionary assumptions and approaching hegemonic and subaltern cultures without judgments about hierarchies of values.”9 Alfred Gell offers further insight into the meanings of technology more generally. He urges us to understand “technology, in the widest sense [as]… forms of social relationships which make it socially necessary to produce, distribute, and consume goods using ‘technical processes.’"10 Finally, Norton emphasizes, “Technology is at once process and product."11 She references “the early modern era,” a chronological term once considered irredeemably Eurocentric, but now accepted in non-European precincts precisely because of the newly shared materialities of this period and their significance.11

I consider the tobacco pipe from these perspectives, exploring entangled goods and peoples that generated new rituals, expectations, and habits in Atlantic communities. Exploring what objects do in discrete cross-cultural colonial environments, Nicholas Thomas has successfully deployed the term ‘entangled’ in respect to Pacific peoples, material culture, and colonialism.12 The notion of entanglement effectively captures complex colonial events, foregrounding active material culture and the communities that fashioned these ways. The pipe, a preeminent tobacco technology, reshaped Europe and its Atlantic colonies, materially and culturally, in diverse and quotidian ways. Feeding these pipes initiated critical new habits and processes, defining regions and peoples.

- 1James Grehan, “Smoking and ‘Early Modern’ Sociability: The Great Tobacco Debate in the Ottoman Middle East (Seventeenth to Eighteenth Centuries),” American Historical Review 111, no. 5 (2006): 1353; Sanjay Subrahmanyam, “Connected Histories: Notes towards a Reconfiguration of Early Modern Eurasia,” Modern Asian Studies 31, no. 3 (1997): 735-62.

- 2Beverly Lemire, Global Trade and the Transformation of Consumer Cultures. The Material World Remade, c. 1500-1820 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018); Giorgio Riello, Cotton: The Fabric that Made the Modern World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); Rebecca Earle, The Body of the Conquistador: Food, Race and the Colonial Experience in Spanish America, 1492-1700 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- 3For example, Judith Ann Carney, Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2001); Judith Ann Carney and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff, In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009); Jace Weaver, The Red Atlantic: American Indigenes and the Making of the Modern World, 1000-1927 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2014); Coll Thrush, Indigenous London: Native Travellers at the Heart of Empire (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2016); Molly Warsh, American Baroque: Pearls and the Nature of Empire 1492-1700 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

- 4See Beverly Lemire, Laura Peers, and Anne Whitelaw, eds. Object Lives and Global Histories in Northern North America: Material Culture in Motion, c. 1780-1980 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2021).

- 5Marcy Norton, “Subaltern Technologies and Early Modernity in the Atlantic World,” Colonial Latin American Review 26, no. 1 (2017): 18-38; Sacred Gifts, Profane Pleasures: A History of Tobacco and Chocolate in the Atlantic World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008).

- 6Thomas Parke Hughes, Human-Built World: How to Think about Technology and Culture (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005).

- 7For example, Peter Burke, What is the History of Knowledge? (Oxford: Polity Press, 2015); Simone Lässig, “The History of Knowledge and the Expansion of the Historical Research Agenda,” Bulletin of the German Historical Institute 59 (2016): 29-58. I thank Rita Nayer for her discussions of the history of knowledge.

- 8Lässig, “The History of Knowledge,” 37.

- 9Norton, “Subaltern Technologies,” 26.

- 10Ibid, 26.

- 11Ibid, 26.

- 11Grehan, “Smoking,” 1353-1354.

- 12Nicholas Thomas, Entangled Objects: Exchange, Material Culture, and Colonialism in the Pacific (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1991), 8-9; “The Case of the Misplaced Ponchos,” Journal of Material Culture 4, no. 1 (1999): 5-20.

The Smoking Pipe: Translation and Inauguration

Over the course of the sixteenth century, coastal and riverine encounters along the American continents became routine, with tobacco eliciting bafflement, curiosity, and then obsession among Europeans. Norton has explored this trajectory for the Spanish empire, revising previous histories of tobacco’s globalization to emphasize the importance of Indigenous American tobacco culture. Historians are in large part dependent on written accounts of tobacco transactions, though archaeological and other material evidence demonstrates the early and rapid adoption of Indigenous tobacco in the sixteenth century, including on the West African coast—pipes, pipe pieces and artistic works mark interactions and adaptations.1

Certainly, written records referencing tobacco are more commonplace in northwest Europe after the mid-sixteenth century. André Thevet (1516-1590), eventually cosmographer to the king of France, was among the first to record cigar smoking by Indigenous people in Brazil in 1557, following a two-year sojourn. He noted that Brazilians considered tobacco to be “wonderfully useful for several things.”1 Thevet later claimed first-hand knowledge of the use of tobacco among the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) peoples along the Saint Lawrence River; importantly, he employed the terminology of perfuming to make the smoke comprehensible to his readers.2 Europeans were deeply versed in the uses of incense and burning herbs for religious, ceremonial, and functional purposes. Thevet’s metaphor was important as an indication of the context in which this herb was placed.3 The aroma of tobacco likely scented the air of European Atlantic ports, as the plant was already notable among seafaring peoples, and became commonplace across a wider geography generations later, even as Thevet announced the arrival of this substance to literate elites. Jean de Léry (1536-1613), a Protestant missionary, added further to formal tobacco lore. Confirming tobacco’s martial value, he claimed that the Tupinamba of Brazil “will go three or four days without nourishing themselves on anything else” following the ritual ingestion of tobacco smoke.4 De Léry also observed tobacco use in Carib ceremonial contexts, recounting that smoking men encircled dancers, blowing smoke into their faces.5

Tobacco rituals marked daily, seasonal, and exceptional events in the Americas.6 Well-read Europeans gradually assembled information on these and other rites. Bit by bit, European-based elites caught up with the hard-won knowledge of unlettered seamen with firsthand accounts of Indigenous practice. Tobacco instruction and use permeated maritime communities. Intermediaries trained in explaining the use of tobacco fitments familiarized new generations with this resonant herb; European cognoscenti followed these leads.7

In the following decades, tobacco apprenticeships took place within countless communities in the eastern reaches of the Atlantic and beyond, as mariners, merchants, and missionaries transmitted their first-hand experiences of this leaf and its rituals in diplomacy, hospitality, and sociability. Their embodied knowledge, along with Indigenous accouterments like pipes, circulated along sea lanes. Tobacco translation ensued, a multi-generational process, imbrications of “process and product,” challenging initiates to slot this technology into local categories of meaning. Europeans and Africans witnessed tobacco’s roles, recognized its potential, and tested its properties in many milieus. The commercial possibilities were clear. Translations were repeated endlessly through embodied practices—hand-to-hand, mouth-to-mouth—and recontextualized by an array of common peoples for a variety of different purposes.

European ties to commoditized tobacco began in the Caribbean in the early-sixteenth century, and local colonists soon understood the potential markets and profits to be had. They also seemed to learn the ways tobacco could be used in the lives of the enslaved, including on Santo Domingo. One account speculated on tobacco’s value to those forced to perform heavy labor: “they say that when they [the enslaved] stop working and take tobacco their fatigue leaves them.”8 Decades before the 1490s, West Africans interacted with Iberian seaborne merchants.9 Little wonder, then, that in the aftermath of these transatlantic voyages, Africans, along with Europeans, were among the earliest outsiders to experience tobacco’s power. African seamen are confirmed among Columbus’s crew on his second foray to the Caribbean in 1494 and, doubtless, thereafter.10

The utility and potential profit from this leaf led to European investments in Venezuela, Brazil and Mexico.11 The preeminent value of this crop was evident to plantocrats, as well as to seafarers of all nations who traded for rations of this herb with Indigenous peoples wherever they could. Systematic colonial cultivation ensued with attempted small-scale farms and larger plantations, even as Indigenous farmers produced for this new market.12 Dutch and English privateers siphoned off Iberian cargoes or bought directly from Indigenous or Iberian settler farmers, despite legal prohibitions. Contraband traffic continued unremittingly, bringing tobacco into the calloused hands of many ranks and ethnicities. This was a matter of world significance, not a top down, but a bottom up adaptation of Indigenous tobacco technologies by predominantly Atlantic based folk, translating and globalizing a key facet of Indigenous American culture.13

The multi-pronged processes of adopting, adapting, and spreading tobacco technology drove the subaltern technology of the tobacco pipe. The pipe, itself, gradually became entangled with massive colonial land seizures and the highly capitalized enslavement of predominantly African populations. These two profoundly important European policies sustained the development of complex, capitalist commodity systems that moved tobacco in bulk to world markets and ensured vast European profits.14 The tobacco pipe evolved in this context, with innovations and manipulations in European, Euro-colonial, and African contexts. As tobacco pipes burgeoned, European tobacco consumers were also instructed in the racial hierarchies foundational to these systems. The use of tobacco pipes and instruction in racial hierarchies were sequential, part of “process and product,” which I discuss below.

A slim 70,000 pounds of tobacco was officially imported into the Spanish city of Seville in 1608—a figure that does not account for the informal traffic with Indigenous and settler farmers, nor with the private trade of ships’ officers and elite passengers, all of which must be recognized as significant.15 The sort of small scale traffic that crisscrossed eastern Atlantic waters included, for example, an English West Country ship in 1609, which transported six bags of pepper, one “pack” of calico, and two hundred weight of tobacco from Lisbon to Bristol.16 Like many ports, Bristol’s waterside taverns were frequented by those familiar with smoking, as well as would-be initiates. My interest here is not to track the timeline of colonization and the development of capitalist markets for this plant, but rather to offer a summary with a few simple numbers to illustrate the pace of change. By 1613, the cargo reaching Seville hit 404,554 pounds.31 “By 1619, Virginians’ sales equaled Spanish sales in London. By 1620, they were twice that.”17 Tobacco plantations flourished in the Chesapeake region of Virginia through African labor, some with experience of tending tobacco in African farms and gardens, now forcibly relocated.18 Between 1686-1688, approximately 36,352,000 pounds of tobacco were imported into England.19 Brazilian tobacco plantations were out-produced by the Chesapeake’s plantations, whose product dominated the key Amsterdam tobacco market. Portugal also received substantial quantities of this commodity from their colony, reaching 4 million pounds annually in 1672.20 The resulting imperial structures provided the foundation for the intersection of material systems and the genesis of new rituals of consumption as Atlantic World populations created and sustained tobacco rituals, an interwoven narrative with few equals.21 Underlying these processes was the might of imperial powers, which drove production of this leaf and built the networks of exchange that intersected lives and cultures. Common people of different ranks and ethnicities, gender and age, innovated within this system, resisting and revising, devising symbolic and spiritual meanings through pipe practice.

- 1a1bArlene B. Hirschfelder, Encyclopedia of Smoking and Tobacco (Phoenix: Oryx Press, 1999), 297.

- 2Marcel Trudel, “Thevet, André,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Vol. 1, accessed Febuary 29, 2016 (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003); André Thevet, “Singularitez de la France antarctique,” in André Thevet’s North America: A Sixteenth-Century View, trans. and ed. Roger Schlesinger and Arthur P. Stabler (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1986), 10-11.

- 3I emphasize this perspective on tobacco as “perfume” in contrast to European writers’ established analysis, which has focused on the medicalization of this plant as an explanation for its popularity among Europeans. In fact, Thevet’s assessment suggests the far wider contextualization among Europeans, not least from the influence of Indigenous practice. For the medicalization of tobacco see Jordan Goodman, Tobacco in History: The Cultures of Dependence (London: Routledge, 1994). For a critique of the medicalization paradigm, Marcy Norton, “Tasting Empire: Chocolate and the European Internalization of Mesoamerican Aesthetics,” American Historical Review 111, no. 3 (2006): 660-689.

- 4Peter C. Mancall, “Tales Tobacco Told in Sixteenth-Century Europe,” Environmental History 9, no. 4 (2004): 653.

- 5Ibid, 655-656.

- 6Johannes Wilbert, Tobacco and Shamanism in South America (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 13-16, 107-108.

- 7For example, Arthur J. Ray, An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native People. I Have Lived Here Since the World Began, 4th ed. (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2016), 36; Joseph C. Winter, “Traditional Uses of Tobacco by Native Americans,” in Tobacco Use by Native North Americans: Sacred Smoke and Silent Killer, ed. Joseph C. Winter (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2000), 9-58; Marcy Norton and Daviken Studnicki-Gizbert, “The Multinational Commodification of Tobacco, 1492-1650,” in The Atlantic World and Virginia, 1550-1624, ed. Peter C. Mancall (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 254-256.<

- 8Norton and Studnicki-Gizbert, “Multinational Commodification”, 256.

- 9Geoffrey V. Scammel, The First Imperial Age: European Overseas Expansion, c. 1400-1715 (London: Routledge, 2004), 38-40.

- 10Christopher C. Fennell, “Early African America: Archaeological Studies of Significance and Diversity,” Journal of Archaeological Research 19, no. 1 (2011): 8-9.

- 11Lawrence A. Peskin and Edmond F. Wehrle, America and the World: Culture, Commerce, Conflict (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012), 21.

- 12Lemire, Global Trade, 199-200.

- 13Ibid, 193-201; Goodman, Tobacco in History, Table 6.1, 143. It is crucial to note that Indigenous Peoples continued and continue to use tobacco in ceremonial practices.

- 14William Darity, Jr. “British Industry and the West Indies Plantations,” in Joseph E. Inikori and Stanley L. Engerman, eds. The Atlantic Slave Trade: Effects on Economies, Societies and Peoples in Africa, the Americas, and Europe (Durham: Duke University Press, 1992), 247-282.

- 15Norton, Sacred Gifts, 143.

- 16“The discourse of Captaine Downes,” The liues, apprehensions, arraignments, and executions, of the 19. late pyrates Namely: Capt. Harris. Iennings. Longcastle. Downes. Haulsey. and their companies. As they were seuerally indited on St. Margrets Hill in Southwarke, on the 22. of December last, and executed the Fryday following. (London, 1609), np (Image 25).

- 31Norton, Sacred Gifts, 143.

- 17Kenneth Pomeranz and Steven Topic, The World that Trade Created: Society, Culture, and the World Economy, 1400 – the Present (Armonk: M.E. Sharpe, 1999), 99.

- 18Anthony S. Parent Jr., Foul Means: The Formation of a Slave Society in Virginia, 1660-1740 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), 60-62.

- 19Robert C. Nash, “The English and Scottish Tobacco Trade in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Legal and Illegal Trade,” Economic History Review 35, no. 3 (1982): 356; Joyce Lorimer, “The English Contraband Tobacco Trade in Trinidad and Guiana, 1590-1617,” in The Westward Enterprise: English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic, and America, 1480-1650, eds. Kenneth R. Andrews, Nicholas P. Canny, and P. E. H. Hair, David B. Quinn (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1978), 124-150; Michael Kwass, Contraband:Louis Mandrin and the Making of a Global Underground (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014), 22-23.

- 20James Lang, Portuguese Brazil: The King’s Plantation (New York: Academic Press, 1979), 111.

- 21The French government made the taxation of tobacco the foundation for state finances, which encouraged wholesale smuggling of this commodity into the country. Kwass, Contraband, 44-53.

The Smoking Pipe: New Tobacco Alliances

Easily pocketed, stored in sea chests and readily breakable, tobacco pipes trickled around the Atlantic over the sixteenth century in unknown numbers—a multi-site circulation. The modest dimensions of some pipes and the range of potential Indigenous American and early colonial sources mark this ephemeral, subaltern technology. However small, this slight thing had disproportionate value to its owner. West African artistic renderings of pipes and the stylistic similarities they share with Floridian Gulf of Mexico and West African pipes suggest the early-sixteenth-century traffic in these wares, doubtless an informal exchange.1 With rising plantation production, consider the steady flow of pipes from hand-to-hand, and the countless initiations that ensued at each port of call, as plebeian sea-borne cognoscenti demonstrated the filling of the pipe bowl, application of fire to set the tobacco leaves alight, and settling to the comfort and reflection of the pipe. All those who endured hard labor—civilian or military—treasured its power.2 Of course, merchants, officials, and churchmen also learned and indulged. Was it the intimacy and immediacy of the pipe that quashed the loud (elite) critiques of “Indian tobacco”? We must take seriously the deep unease in some quarters, as colonial engagement with Indigenous Americans and the vast enslavement of Africans built new concepts of race.3 Some commentators agonized over tobacco and its creolizing potential, equating pipe smoking with sexual congress with an “Indian whore,” and seething against becoming “Indianized with the intoxicating filthie fumes of Tobacco.”4 A coterie of elites sustained objections, including King James of England and Scotland (1566-1625), who wrote of “the dislike Wee had of the use of Tobacco, tending to the general and new corruption both of mens bodies and maners.”5 In 1604, James asked “what honour or policie can move us to imitate the barbarous and beastly maners of the wilde, godlesse, and slavish Indians, especially in so vile and stinking a custome?”6 The peril of Indian-ness defined his disquiet. Fearing the corruption of European men’s bodies, James saw tobacco as a potential pollution that might undo their manliness—a theme repeated in European kingdoms engrossed in American colonization.7

Protests over tobacco use resounded. Yet the pipe persisted. Its increased presence contrasts sharply with the objections voiced by the high-rank echo chambers where written objections were bruited; complaints in those realms differed sharply with the ship-board, harbor-side, street-level, tavern-based personal encounters with the pipe—experiences that included well-placed elites. Dining rooms and private libraries were eventually populated by pipe-lovers. A wonderfully gestural device, hand-held pipes were smoothly warm to the touch and issued cycles of physical sensation that came with the glow of the coals and the evanescence of the smoke. Every treatise against tobacco issued from the sixteenth century onwards faced, as a counterpoint, the challenging and pervasive materiality of the pipe.

Leora Auslander argues for the particular importance of objects “that are not just seen, but also felt and touched. These goods . . . carry special weight in essentially all societies . . . used in everyday, repetitive embodied activities . . . not simply functional.”8 She continues with the succinct observation that “Artifacts, therefore, are differently informative than texts even when texts are available; texts, in fact, sometimes obscure the meanings borne by material culture.”9 Tangible and multi-sensory, the intimacy of smoking devices, and their rapid proliferation from the late-sixteenth century, effectively contested intellectual retorts against “the drinking of smoke.” Though friable, the clay pipe held enormous power.

Clay pipes were the ultimate early modern subaltern technology, as evidenced by Atlantic-world landscapes of exchange. They served as vehicles of cross-cultural translation with repeated processes of domestication and were ultimately made in vast quantities in countless settings throughout Europe, its colonies, Africa, and other Atlantic world locales. Though sometimes differently gendered, among different ranks, and in different locales, these ubiquitous cultural tools impacted early modern populations. There is typically a multi-step process that precedes a new manufacturing venture: seeing and understanding the foreign (Indigenous) model, identifying processes of replication, experimentation, and then putting small-scale works in action. Tobacco was commonly grown “about every mans [sic] house,” reported an English seafarer visiting Sierra Leone around 1600. African-made clay pipes were a familiar sight in West Africa by the mid-sixteenth century. Around 1600, these long-stemmed pipes were reportedly “made of clay well burnt in the fire . . . [with] both men and women drinking the most part down [of the smoke].”10 Material translations took various forms as they moved across cultural spaces.11

- 1Lemire, Global Trade, 202-4; John Edward Philips, “African Smoking and Pipes,” Journal of African History 24, no. 3 (1983): 307-8.

- 2Norton, Sacred Gifts, 30. Spanish troops possibly introduced tobacco smoking to the Low Countries during the Dutch Revolt (1568-1648). Woodruff D. Smith, Consumption and the Making of Respectability, 1600-1800 (New York: Routledge, 2002), 161-162; Wim Klooster, “The Tobacco Nation: English Tobacco Dealers and Pipe-Makers in Rotterdam, 1620-1650,” in The Birth of Modern Europe: Culture and Economy, 1400-1800. Essays in Honor of Jan de Vries, eds. Laura Cruz and Joel Mokyr (Leiden: Brill, 2010), 21. Tobacco also became central in coercive systems of consumption, employed to discipline and control key labor force—a subject addressed elsewhere. Lemire, Global Trade, 223-232.

- 3Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004); “Accounting for ‘The Most Excruciating Torment’: Gender, Slavery, and Trans-Atlantic Passages,” History of the Present 6, no. 6 (2016): 184-207.

- 4John Deacon, Tobacco Tortured, or, The Filthie Fume of Tobacco Refined (London: Field, 1616), 10, quoted in Sabine Schülting, “‘Indianized with the Intoxicating Filthie Fumes of Tobacco’: English Encounters with the ‘Indian Weed,’” Hungarian Journal of English and American Studies 11, no. 1 (2005): 110.

- 5By the King [James I], A Proclamation for restraint of the disordered trading for Tobacco, (London: Robert Barker, and John Bill, printers to the Kings most Excellent Majestie,1620).

- 6King James I of England, A Counterblast to Tobacco (London, 1604).

- 7Rebecca Earle argues for the importance ascribed by Spanish colonizers to the European foodstuffs they ate as a way to mitigate the new environment of the Americas, “in the construction and maintenance of the colonial body.” Complications ensued as diets changed. Earle, The Body of the Conquistador, 11.

- 8Leora Auslander, “Beyond Words,” American Historical Review 110, no. 4 (2005): 1016-1017.

- 9Ibid, 1016-1017.

- 10Observations of William Finch, Merchant, Taken Out of His Large Journall. I. Remembrances Touching Sierra Leona, in August 1607, in Samuel Purchas, Purchas His Pilgrimes. In Five Bookes (London, 1625), 415; Barbara Plankensteiner, “Salt-Cellar,” in Exotica: The Portuguese Discoveries and the Renaissance Kunstkammer, eds. Helmut Trnek and Nuno Vassallo e Silva (Lisbon: Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, 2001), 93-94.

- 11Tobacco pipes were also a subject of curiosity for Richard Jobson. He ascended the Gambia River in 1620, travelling many hundreds of miles to arrive ultimately to the Tenda region in what is now Senegal. Among his observations are comments regarding the ubiquity of the tobacco pipe inland. He writes, “Few or none of them [men and women] . . . doth walke or go without.” The bowls of the pipe were also decorated “very handsomely, all the bowles being very great, and for the most part will hold halfe and ounce of Tabacco [sic].” Richard Jobson, The Golden Trade: Or, A discovery of the River Gambra, and the Golden Trade of the Aethiopians (London: Nicholas Okes, 1623), 122.

Fig.1 Clay tobacco pipes, London, England, 1580-1590. Courtesy of the Science Museum, London. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

The Wellcome Collection holds clay pipes dated from 1580-1590 London, expressing the pervasiveness of pipe smoking in that time and place, decades before England emerged as an imperial power (Figure 1). What was termed a “Mexican” tobacco pipe apparently inspired English artisans and investors, pointing to webs of exchange that transected formal imperial networks. The pipes in Figure 1 likely shared features with eponymous pipes from Indigenous Americans that travelled along the trade routes from Iberia, or, indeed, from the Caribbean or eastern North America. Regional pipe workshops opened in London in the 1570s and later in ports like Bristol, Chester, Hull, Newcastle, and Gateshead. Edinburgh and other centers in Scotland also hosted this trade, as did Dublin, Limerick, and Cork in Ireland from the 1660s onwards; by this time, the Netherlands and areas of France stood as a major pipe-making centers.1 Importantly, clay pipes left a substantial physical record around the margins of the Atlantic basin, markers of early modern material entanglement.2 Few subaltern technologies bequeathed such robust physical evidence and engaged the energies of so many archaeologists and amateur enthusiasts, while demonstrating ubiquity so emphatically.3 A pipe-making oven was even part of the early English colonial venture in 1607 Jamestown, Virginia.4 Settlers did not want to depend on proximate Indigenous peoples for essential tools.

Recall, once again, Norton’s observation that “Technology is at once process and product.”5 The pipe was an appliance that both introduced and sustained tobacco smoking, ultimately a synonym for the plant itself and its colonial exploitation. Pipe making advanced in scale from the late 1500s, across a broad geography, enabling personal rituals, endlessly repeated, with ever more numerous participants, a critical addendum to imperial systems, embodied and reified. Pipe smoking was infinitely replicable while allowing for idiosyncratic innovations. Local practices, outside metropoles, demonstrate the penetration of this technology. For example, in the Atlantic-facing port of Galway in western Ireland, pipe smoking was pervasive by at least 1600, and essential for routine sociability. Galway’s investment in the colonial Caribbean helps explain this phenomenon in this northwestern region of the European archipelago.6 In what follows, I will return to the particularities of tobacco use in Ireland that subsequently evolved, moving from secular to sacred.

- 1Klooster, “The Tobacco Nation,” 28; Dennis Gallagher, “William and John Banks; Evidence Relating to the Early Manufacture of Clay Tobacco-Pipes in Edinburgh,” Society for Clay Pipe Research Newsletter 3 (1984): 1-13; Ruairí Baoill and Paul Logue, “Excavations at Gordon Street and Waring Street, Belfast,” Ulster Journal of Archaeology 64 (2005): 106-319; Bob Will and Tom Addyman, “The Archaeology of the Tolbooth, Broad Street, Stirling,” Scottish Archaeological Journal 30, no. 1/2 (2008): 111, 116, 134; David R. Perry, Castle Park, Dunbar: Two Thousand Years on a Fortified Headland (Exeter: Short Run Press, 2000), 171-172; Also see The Society for Clay Pipe Research http://scpr.co/ for detailed examples of pipe makers and archaeological findings.

- 2Naseema Hosein-Hoey, “Clay Tobacco Pipes (Bowls and Stems)” in Encyclopedia of Caribbean Archaeology, eds. Basil A. Reid and R. Grant Gilmore (Gainesville: University of Florida, 2014), 105-106; Robert H. Pritchett III and William K. Selinger, ARS Shipwreck Projects Dominican Republic, Vol. 1 (Never Mind Publishing, 2010), 129-130.

- 3A. Oswald, Clay Pipes for the Archaeologist (London: British Archaeological Reports, 1975), 28; Alexandra Hartnett, “The Politics of the Pipe: Clay Pipes and Tobacco Consumption in Galway, Ireland,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 8, no. 2 (2004): 133-147; Klooster, “The Tobacco Nation,” 17-34; for example, Andrew Sharp, “William and John Banks; Evidence Relating to the Early Manufacture of Clay Tobacco-Pipes in Edinburgh,” Society for Clay Pipe Research Newsletter 3 (July 1984), 1-6; Diane Dallal, “The Tudor Rose and the Fleur-de-lis: Women and Iconography in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Clay Pipes found in New York City,” in Smoking and Culture: The Archaeology of Tobacco Pipes in Eastern North America, eds. Sean Rafferty and Rob Mann (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2004), 207-239; for archaeological findings of clay pipes in seventeenth and eighteenth century Newfoundland, see: https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/pipemarks-introduction.php; Ivor Noël Hume, “Hunting for a Little Ladle: Tobacco Pipes,” CW Journal (Winter 2003-2004) https://www.history.org/foundation/journal/winter03-04/pipes.cfm; for examples from the United Kingdom, see Sarah Newns, “Appendix 3: Excavations in 2014 at Wade Street, Bristol - a documentary and archaeological analysis,” Internet Archaeology 45 (2017), https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.45.3.4.

- 4Jeffrey L. Sheler, “Rethinking Jamestown,” Smithsonian 35 (2005): 48-55.

- 5Norton, “Subaltern Technologies,” 26.

- 6Hartnett, “The Politics of the Pipe,” 133-137. See also, Joe Norton, “Pipe Dreams: A Directory of Clay Tobacco Pipe-Makers in Ireland,” Archaeology Ireland 27, no.1 (2013): 31-36.

Englishmen apparently transplanted pipe making to the Netherlands in the early 1600s as an adjunct of war and the provisioning of troops; of the seventeen pipe makers in Amsterdam before 1620 ten were Englishmen. Gouda flourished as another pipe making center and the port of Rotterdam thrived in supplying other European markets with this gear, along with African and wider Atlantic trade.1 Where production numbers survive, they show the striking measure of manufacture. Daily output from individual pipe makers in the city of Gouda ranged between 1000 to 1500 pipes, with 80 members of the pipe makers’ guild in 1665, 223 members in 1686, and 611 members in 1730, each heading his or her own works.2 Even a conservative estimate confirms the tens of millions of pipes made annually, solely by the Dutch, by the mid-seventeenth century.

- 1Klooster, “Tobacco Nation,” 17-34; Society for Clay Pipe Research Newsletter 3 (July 1984); Joan Thirsk, Economic Policy and Projects: The Development of a Consumer Society in Early Modern England (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1978), 6, 111; Dallal, “Tudor Rose,” 212.

- 2Jan De Vries and Ad van der Woude, The First Modern Economy: Success, Failure, and Perserverance of the Dutch Economy, 1500-1815 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 309-310.

Given the simple composition of this device and the extensive manufacturing, pipes were cheap. A 1694 English report outlined the price range: “Ordinary Pipes are sold for Eighteen Pence the Gross and Glassed ones for Two or Three Shilling.”1 Thus, the cheapest pipe cost half a farthing, or an eighth of a penny, bringing pipes to the lips of all but the poorest man, woman, or child. Even beggars were expected to have their own pipes in eighteenth-century France.2 And the respectable working poor in early modern Amsterdam, who did not have the means at hand, used shop credit to secure essential tobacco pipes.3 All European oceanic shipping carried stocks of pipes and so, too, did the grocers, chandlers, tobacconists, tavern-keepers, and peddlers in situ. Peddlers funneled tobacco pipes through rural byways and city lanes, like the Lincolnshire peddler, in the northeast of England, who had half a gross of tobacco pipes at the time of his death in 1613, worth a fraction of a penny each.4 A late-seventeenth-century Nuremburg shopkeeper who supplied regional peddlers had Dutch and Spanish tobacco in stock, among many other necessaries.5 European peddlers in various regions, both with shops and on foot, carried precisely those goods most in demand—tobacco and its accessories fit the bill.6

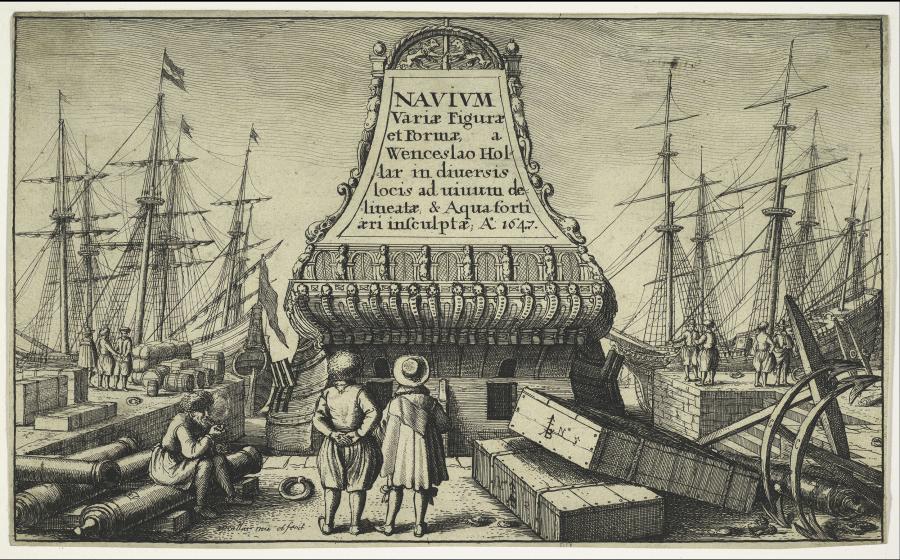

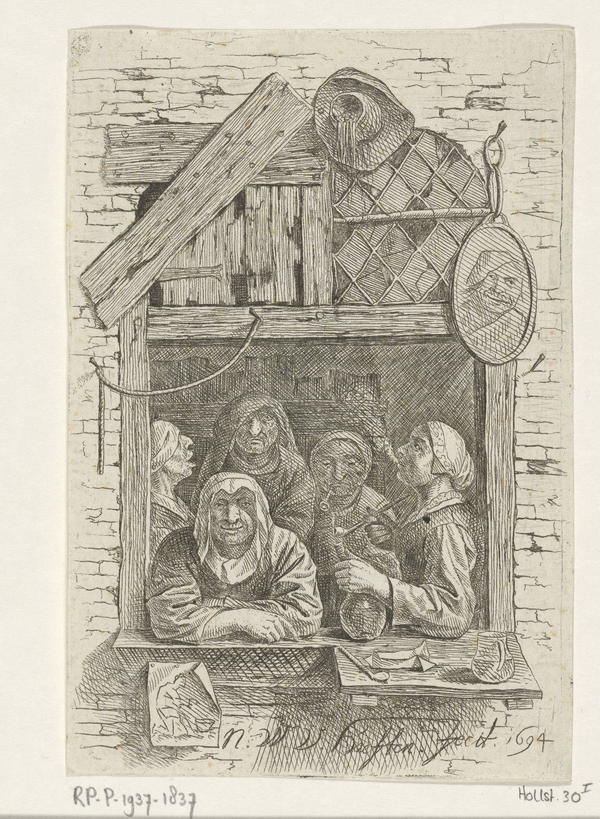

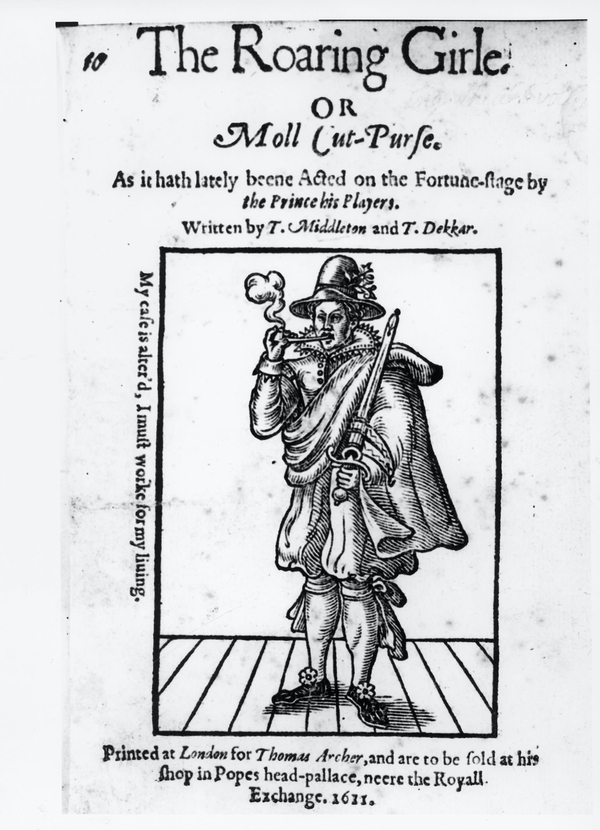

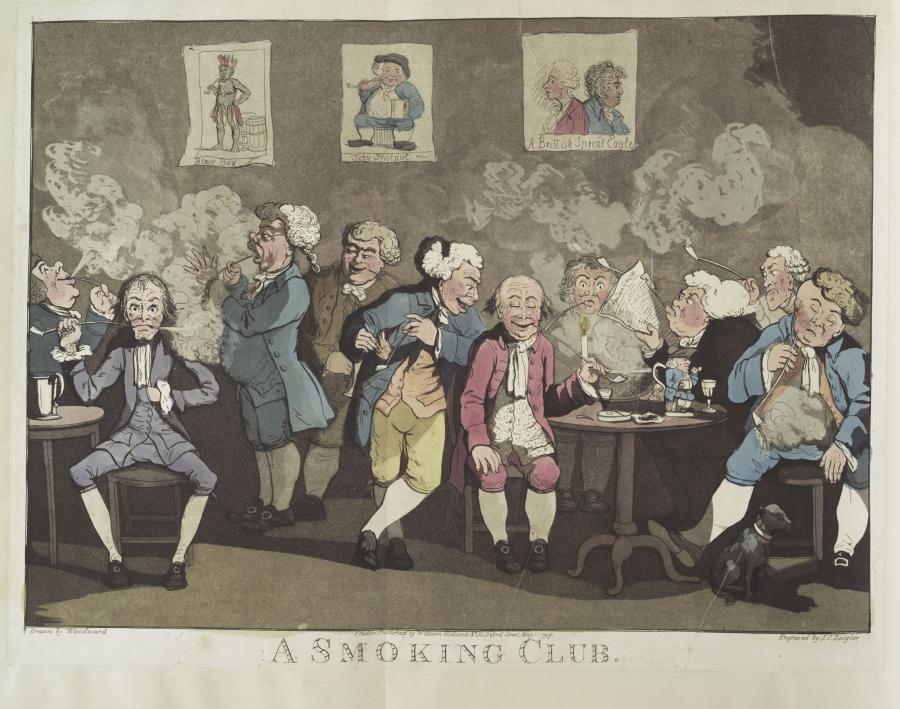

European artists often mingled with common folk, rural and urban, recording and interpreting their surroundings and its characters for patrons or wider print sales. Collections of paintings and prints from the late 1500s and 1600s feature countless scenes of tobacco-infused repose: a well-earned rest by hard-working men or the louche indulgences of pocket-poor ne’er do wells. Artists from the Low Countries were especially active in these genre scenes. The tobacco routinely inhaled, the pipe stems touching smokers’ lips, were leitmotifs of this era, recorded in fine art or cheap prints in ever-greater forms, adding to visual tropes of the smoking figure. Figure 2 is a detail from the title page of a volume celebrating Dutch ships and shipping. The left-hand figure exemplifies this age. Pipe in hand, he sits taking his ease on a cannon, ready to be loaded on board. The cannon and the man were both essential to protect and preserve the tide of tobacco shunted across the Atlantic. Artists like David Teniers captured a scene with less obvious imperial associations. In Figure 3, for instance, Teniers illustrates bricklayers marking the day’s end with pipes in hand. A pipe with a broken stem lies on the floor by the bricklayers’ tools. Five Women in a Window (Fig. 4) offers a differently gendered depiction of working women’s relaxation, with jug, pipes, tankard, and smoke fuming the air. While laboring men are more commonly the subjects of artistic works of this theme, women also embraced the possibilities that came with feeding the pipe.

Everyday actions make meanings in ways as important as grand pageants. The spread of Indigenous novelties, like tobacco and tobacco pipes, sparked new gestural lexicons marking the age. Note the ways pipes are held in careful balance, the bowl sometimes askew. There is a profound relationship between gestures, culture, and associated tools. As French historian of science Luce Giard observes, this is a process that “involves not only the utensil or tool and the gesture that uses it, but the instrumentation relationship that is established between the user and the object used.”7 Men and women learned the glassy feel of warm pipe bowls and embraced the full mouth of smoke, deploying this intimate (public) possession in various culturally constructed modes. The imperial system was thus embodied through this habit and technology. Equally, in European and Euro-colonial settings tobacco pipes materialized instructions about race.

- 1“Tobacco Pipe Clay, where got: What Price… How Many Made a Week…”. Collection for the Improvement of Husbandry and Trade (London: 1693/4), N.P.

- 2Kwass, Contraband, 26.

- 3Anne McCants, “Goods at Pawn: The Overlapping Worlds of Material Possessions and Family Finance in Early Modern Amsterdam,” Social Science History 31, no. 2 (2007): 225.

- 4Margaret Spufford, The Great Reclothing of Rural England: Petty Chapman and Their Wares in the Seventeenth Century (London: Hambledon Press, 1984), 66.

- 5Laurence Fontaine, History of Pedlars in Europe, trans. Vicki Whitaker (Durham: Duke University Press, 1996), 28.

- 6Spufford, Great Reclothing, 66, 178-179; Fontaine, History of Pedlars, 28-32; Kwass, Contraband, 82.

- 7Michel de Certeau, Luce Giard, and Pierre Mayal, Practice of Everyday Life: Living and Cooking, Vol. 2, trans. Timothy J. Tamasik (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1998), 211.

The Smoking Pipe: Ritual, & Race

Historian of Indigenous peoples in urban locales, Coll Thrush brings a different perspective to the question of race and the learning of racialism. He notes that “London had to learn to be colonial”—so, too, did other European citizens and settlers of the Atlantic regions.1 Instruction in race occurred variously and sporadically including among the unlettered, whether through direct experience on slave ships or plantations or more indirectly through the rising tide of figurative printed and material media that depicted new racial hierarchies. I first explored the question of “racialized consumption” in my recent volume on global trade and material change. I contend that western tobacco consumption held racialized categories at its core, shaping this new “instrumentation relationship.” Of course, the systems of consumption within colonial and metropolitan spheres were not monolithic, especially as African and Native American tobacco practices persisted and resisted hegemonic control.2 Those resistant systems are not my focus here.3 Rather, I explore the power of racialized consumption at a time when western perspectives of non-European peoples were in flux, premised on emerging racialized imperial precepts.

Jennifer Morgan traces travel writers’ descriptions and the growing racialized perspectives they developed of African women—views that percolated through literate European culture.4 These texts, along with more mechanistic records like account books and ship logs, document the commoditization of specific dark-skinned populations and the associated justifications that ensued in Enlightenment Europe. Michel-Rolph Trouillot wrote of the “Certain Idea of Man,” which emerged in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, stating “The more European merchants and mercenaries bought and conquered other men and women, the more European philosophers wrote and talked about Man”— or a certain idea of (White) man.5 Subaltern Europeans manned slave ships, fought in colonial contests, and seized lands from Indigenous communities, often learning of their White status through these encounters.6 But how did the mass of unlettered European women and men learn the tropes of race through other-than-alphabetic, numeric, or face-to-face means? Evidence of instructional media survive in museum collections: tobacco trade tokens, ceramics, and demotic prints like tobacco trade cards and wrappers, as well as cheap accoutrements aligned with tobacco use unearthed in archaeological digs. As a racializing system was put in place, these materials served as primers, undergirding the economic and legal structures of slavery. As Leora Auslander reminds us, “objects not only are the product of history, they are also active agents in history. In their communicative, performative, emotive, and expressive capacities, they act, have effects in the world.”7

- 1Coll Thrush, Indigenous London, 36.

- 2Lemire, Global Trade, 190-247.

- 3Some of those issues are address in Lemire, Global Trade, 190-247, as well as in my forthcoming article, “Material Technologies of Empire.”

- 4Jennifer L. Morgan, Laboring Women: Reproduction and Gender in New World Slavery (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), esp. chapter 1.

- 5Michel-Rolph Troulliot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Books, 1995), 75.

- 6Marcus Rediker, The Slave Ship: A Human History (New York: Viking, 2007), 187-221.

- 7Leora Auslander, “Beyond Words,” 1017.

Quotidian material culture informed the habits and ceremonies of life, building narratives and stereotypes that affirmed the rightness of colonial conquest and the unique pleasures for White westerners in a pipe of tobacco, the whole resting on the systematic subjugation of peoples of color. Maps and atlases depicted colonial contingencies, though this print media circulated within a narrow slice of society. Trade tokens were among the plebeian goods that arose in England in the later seventeenth century, used as informal currency where small coins were scarce. These multiplied in the mid-seventeenth century with the rise of small businesses that they advertised, including taverns and tobacconists. Among the symbolism used by this sector was imagery of racial difference, as well as racialized satires, all combining to instruct as customers learned the imperial connections that brought tobacco to hand (Figs. 5-6).

Fig. 7 Gaitskell's Neat Tobacco at Fountain Stairs Rotherhith Wall; Capt Smith . . . taking King of Palpanegh prisoner, engraving, ca. 1745-1865, New York Public Library Digital Collections (1107724)

Fig. 8. “Tobacco Dealer's Trade Cards,” etching, ca. 1725, New York Public Library Digital Collections (b12482883)

Large collections of trade tokens are held at the British Museum and Museum of London. On tobacco or tavern-related tokens we find semi-naked Indigenous Americans and African boys with a pipe or holding a leaf or roll of tobacco. Deployment of nakedness was developing as a key sign of “savagery,” as catalogues of world peoples were put in place by Enlightenment thinkers, merchants and colonists.1 Tokens with these figures arose from London businesses in the most dynamic commercial and shipping districts like Cheapside, Smithfield, Spitalfields, Tower Hill, Wapping, and Southwark. Outside London, tokens with these motifs were issued in all quarters of England, from Devon to Lancashire and Kent.2 Surviving tokens were often rubbed nearly smooth, suggesting years of handling and routine inspection—these coins could only be redeemed at the issuing premises, which provided an incentive for close looking.3 There was a common elision of ethnicities in tobacco advertising, with heterogeneous dark-skinned figures, often wearing tobacco leaf skirts. Historian Emma Rothschild reflects on the imperfect geographic knowledge among the English in the eighteenth century—an observation that fits as well for Europeans of this era. She notes the need “to try to imagine what it was like to have only a very indistinct idea of the difference between the East and West Indies, or America.”4 This scant understanding is apparent in trade tokens, as well as later printed trade cards and advertising, where one dark-skinned body served for another. Nonetheless, the tokens’ connections to tobacco, pipes, and empire are clear. A new symbolic system was created that became a metonym for tobacco itself and for the circumstances whereby pipes were filled and enjoyed: Indigenous Americans and African figures holding pipes denoted the way tobacco was supplied to imperial powers, through the violent appropriation of Indigenous land and the enforcement of African slavery. Cultural theorist Stuart Hall notes the value of “interrogating stereotypes [which] makes them uninhabitable. It destroys their naturalness and normality.”5 Similarly, uncovering the genesis of racial stereotypes can also “destroy their naturalness and normality.”6 Over generations, a racialized culture of consumption was appended to tobacco ingestion in the west, resolving initial anxieties about the herb, now a hallmark of imperial systems that knitted together distant landscapes, with extractive processes that sustained the intimacy of the pipe (Figs. 7-8).

Printed images were rife on eighteenth-century trade cards, tobacco papers, and billheads, reiterating racialized themes in elemental terms on materials that circulated far more widely than the published theses of the century before.7 How people understood these images might depend on personal histories. However, the repeated presentation of racialized caricatures, of the stages of colonization laid bare, and the colonial winners made plain (as in Fig. 7) built a powerful cultural framework, reinforced through repeated everyday looking, touching, and smoking, as well as repeated interactions with tobacco print ephemera. The vulnerability of the early Jamestown settlement was rhetorically erased with the image of valiant Captain Smith victorious over an Indigenous warrior. Imperial myths were reproduced on disposable printed tobacco paper, to be seen, wondered at, and absorbed. Over the eighteenth century, print media dedicated to this crop multiplied, aimed at common consumers who might regularly visit a tobacconist’s shop or need a reminder of a tobacco retailer. Figure 8 fully articulates the systems put in place and the relations of White settlers and Africans: a planter sits with pipe in hand, overseeing his wealth in land, plants, and people. Africans are shown growing, harvesting, and packing barrels of precious leaves to ship abroad. The imperial sun shines over this setting. The tobacco trade was explained through these materials, translated and domesticated, while being steeped in racial precepts. Trade cards were accompanied by blue and white tobacconists’ jars, many with figurative decoration, as in Figure 9. Such imagery emphasized the plantation origins of the leaf, often with an eponymous dark-skinned figure and the cargo ship just visible on the right side. These visualizations accompanied the buying of tobacco to feed the pipe. The comfortable emotions tied to smoking were readily aligned with these scenes and the colonial relations they referenced. Instructions in new racial norms were enmeshed with a habit requiring daily or hourly attention and repeated visits to suppliers where visual instruction recurred.8 Further, racialized tobacco media was not sequestered in just one part of the process of feeding the pipe.

- 1Morgan, Laboring Women, 20-21, 29-30; Grace Karskens, “Red Coat, Blue Jacket, Black Skin: Aboriginal Men and Clothing in Early New South Wales,” Aboriginal History 35 (2011): 1-36.

- 2H. S. Gill, “Seventeenth Century Devonshire Tokens, and their Issuers, not Described in Boyne’s Work,” Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society 16 (1876): 251-265; H. W. Rolfe, “Kentish Tokens of the Seventeenth Century (Continued),” Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Numismatic Society 3 (1863): 58-63; George C. Williamson, Trade Tokens Issued in the Seventeenth Century in England, Wales, and Ireland, by Corporations, Merchants, Tradesmen etc., Vol. 1 (London: Elliot Stock, 1889), 90, 325, 350, 401, 542, 597, 638, 669, 673, 690, 695, 699, 719, 739, 741, 750, 776, 783, 787, 790; John Younge Akerman, Tradesmen’s Tokens Current in London and Its Vicinity Between the Years 1648 and 1672 (London: J. R. Smith, 1849), 60, 131, 142, 187, 231, 237. Additional examples appear in the British Museum’s collection of trade tokens such as the 1671 and 1649-1672 Macclesfield tokens, T.303, T.305, the 1668 Watford token, 1993,0422.192, the token from Canterbury, T.1608, dated 1649-1672 and the 1669 token from Kingston Upon Hull for the Black Boy Tavern, 2001,0602.148, depicting a figure with a bow and arrow.

- 3Williamson, Trade Tokens, 695; Akerman, Tradesmen’s Tokens, 187.

- 4Emma Rothschild, The Inner Life of Empire: An Eighteenth-Century History (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011), 60.

- 5Stuart Hall, “Contesting Stereotypes – Taking Images Apart” in Stuart Hall: Representation & the Media. Transcript, eds. Sanjay Talreja, Sut Jhally and Mary Patierno (Northampton: Media Education Foundation, 1997), 21.

- 6Ibid, 21.

- 7Catherine Molineux, “Pleasures of the Smoke: ‘Black Virginians’ in Georgian London’s Tobacco Shops,” William and Mary Quarterly 64, no. 2 (2007): 327–376.

- 8Lemire, Global Trade, 233-247.

Cheap tobacco jars were routinely embellished with finials or lid handles in the shape of African heads: stereotyped or satiric (Fig. 10). This iconography was not chosen randomly as racialized links were repeated, relentlessly shaping perceived equations between dark-skinned colonized peoples and the majority of White consumers. Inexpensive lead jars were made in increasing quantities from 1750 onwards and archaeologists have unearthed the head finials across Britain, discoveries catalogued on the online Portable Antiquities Scheme.1 Eighteenth-century British- and Dutch-made jars of this type also circulate today on auction sites.2 These items reiterate the breadth of cheap racialized media attached to the refilling of pipes. Lead jars decorated in this manner were much cheaper than large blue and white ceramic tobacco jars; but all shared a common purpose in educating provincial, metropolitan, and White colonial people. Consider as well the repetitive process as men and women used these cheap lead jars, handling the molded heads every time they extracted tobacco or refilled the small canister. The routine physicality of these engagements effected further layered instruction, as another “instrumentation relationship” was consolidated. These jars demonstrate the breadth of inexpensive racialized media attached to the simple task of feeding a pipe.3 Reflect again on the “special weight” of things “felt and touched” and the power of this visual and tangible media is apparent.4

This mass of ephemeral things performed distinctive cultural labor in support of imperial ambitions and western cultural aims. Indeed, the “disorder” feared by King James wrought by the craze for smoking never arose in the ways he foretold. Rather, tobacco consumption and its apparatus buttressed new imperial systems.5 This involved the cultural and commercial appropriation of a previously alien (Indigenous) leaf and the re-orienting of this substance in support of an imperial system premised on race. As Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose assert, “The story of race was naturalised, [and] made part of the ordinary ‘other.’"6 The materialization of racial tropes continued from the late-eighteenth century, as British and European pipe makers decorated pipe bowls with African figures and African heads, adding to the “Blackamoor” jewelry, accessories, and furnishings, which circulated widely in these markets. Black feminist scholar Shirley Anne Tate explains that stylized “Blackamoor figures” reflect “fantasies of racial conquest, ownership of Black bodies with figures as proxies, and possibly contempt for the African enslaved.”7 Smokers accepted and enfolded this racialized materiality into everyday life, aligned with their pleasures.8

- 1https://finds.org.uk/database/search/results/q/african. Accessed 19 November 2020.

- 2For example, “Rare 18th Century Lead Tobacco Box,” Selling Antiques, accessed July 10, 2020, https://www.sellingantiques.co.uk/627829/rare-18th-century-lead-tobacco-box/; “c1800 Georgian Lead Tobacco Jar with Slave Head,” EBay, last modified October 25, 2018, ebay.co.uk/itm/152484315381.

- 3There are extensive surviving handles of this type excavated across Britain. For example,WMID-BA849D, Birmingham Museums Trust; DYFED-A3A69A Carmarthenshire, Wales,; DENO-B29CE9, Derby Museums Trust; DUR-583F05, Durham County Council; NLM-C8727C, NLM-4059C6, NLM-B59847, NLM-63D891, NLM-9BD95F, North Lincolnshire Museum; SUSS-65ACE1, Sussex Archaeological Society; CPAT-1A3426, SWYOR-F721A9, West Yorkshire Archaeology Advisory Service; DENO-BA3665, LVPL-DA527E, LVPL 1201, DYFED-A3A69A, The Portable Antiquities Scheme, https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/943743 accessed 14 July 2019. Also, Science Museum Group, Cylindrical lead tobacco jar, English, 1790-1830, A220553, Science Museum Group Collection Online, accessed July 14, 2019.

- 4Auslander, “Beyond Words,” 1016.

- 5Proclamation for restraint of the disordered trading for Tobacco.

- 6Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose, “Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire,” in At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World, eds. Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 23.

- 7Shirley Anne Tate, Decolonising Sambo: Transculturation, Fungibility and Black and People of Colour Futurity. (Bingley: Emerald, 2019), 113.

- 8For an example from the late-nineteenth century, see WMID-5EFB84, Birmingham Museums Trust; For an example from Carmarthenshire, Wales, see “DYFED-AEB9E5: A Modern Pipe (Smoking),” Portable Antiquities Scheme, last modified October 2019, https://finds.org.uk/database/artefacts/record/id/938485; In the later-nineteenth century, manufacturers used meerschaum to produce high end carved pipes, such as the late nineteenth-century Austrian carved meerschaum pipe in the Wellcome Collection, “Carved Meerschaum Pipe, Vienna, Austria, 1871-1890,” Wellcome Collection, accessed July 14, 2019, https://wellcomecollection.org/works/zn5h7cny.

The Smoking Pipe: Materials & Rituals

Rituals of the pipe marked major translational processes. Feeding tobacco pipes, a quotidian routine, made race an ever-present, everyday component of local rituals. This was a foundational feature of the pipe, evident in European-wide media and enfolded in Atlantic world politics and commerce. Yet pipes were an agential tool in ceremonial and lifecycle events, the clay seemingly molding itself to become part of myriad life passages.

Pipes and pipe-making illuminate a complex domestication. Pipes were shaped of simple clay, an often white or sometimes red substance, and their value increased over time. There were also variations in the pipes, reflecting the tastes of the makers or communities, with initials and regional symbols impressed into the pipes themselves, celebrating the attempted rendition of this device from an Indigenous tool to an essential in Atlantic spaces.1 Archaeologists have uncovered a vast array of evidence, often housed in museums and broken, which demonstrates the commonest technology of subaltern consumption. In Europe, the clay itself and the imprints on the pipes were claims for the transculturation of tobacco. Rather than purely commercial or benign decoration, the marks on tobacco pipes confirm explicit claims—claims made through conquest, trade, and plantations. Stamps of the Tudor rose, castles, makers’ initials, or the names of towns denominated these declarations—in Scotland this included the names of Edinburgh and Glasgow, the latter emerging as a preeminent tobacco port.2 Incised or stamped clay pipes from the Netherlands similarly record their makers, their locales, and sometimes the date of production, signaling their owners’ and makers’ complex intent and purpose, even as the pipes held prospects of pleasure.3

Tobacco culture diversified along various pathways, including in Europe. Some new tobacco rituals were unanticipated by authorities, involving formal observances such as memorial events. Layered meanings accreted one into the other. Indigenous tobacco usage always includes ceremonial and spiritual practice. The possibility of direct influence in these ceremonies between Indigenous communities and the Celtic regions of Britain remains undetermined. Ultimately, both Scotland and Ireland employed tobacco pipes during multiday funeral activities and several Scottish funerary clay pipes (or dregy pipes) survive from the late-seventeenth century in the collections of the University of Aberdeen.4 Folkloric and historical accounts note the importance of keeping adequate stores of pipes and tobacco to see the dead into the next world and to be shared by the community of mourners. In rural Ireland, the body was attended for several days and nights before the burial by the night watchers with pipes and tobacco. In all parts of Ireland, these supplies were placed proximate to the corpse in accordance with local observance: at the head, feet, or on the chest of the deceased. A familiar fragrance during the nights of vigil, pipe smoke lingered as a transitional essence between earth and sky. Each pipe was to be followed by a prayer for the dead, with official watchers often joined by family and friends.5

The integration of pipe smoke into memorial ceremonies (as an unofficial adjunct to incense at mass) bespeaks the full investment of non-elite communities in the power of the pipe. These practices persisted into the nineteenth century, as Maria Edgeworth recorded in 1810, “Even beggars when they grow old, go about begging for their own funerals; that is, begging for money to buy a coffin, candles, pipes, and tobacco.”6 Funerals knit communities together generationally with songs, observances, and expected hospitality that, from at least the seventeenth century, included tobacco and pipe. Later authorities in Ireland attempted to constrain what they saw as needless expenditure or “abuses” among the poor. Nevertheless, a generous supply of “whiskey as well as pipes and tobacco, bread, meat, etc.” was a sign of respect for the dead that rebounded as well on the family.7 In this case, official instructions held little weight.

It is evident from the surviving material remains that colonial populations modified tobacco customs in accordance with their traditions and contexts (though debates persist on makers and meanings of colonial pipes).8 Archaeologists describe distinct geographic spaces in the plantation settlements of Tidewater Maryland and Virginia where different populations found time and space for their pipes. Examples unearthed in the Chesapeake area indicate the complexities of regional colonial consumption, including the making and using of pipes by Africans, Indigenous Americans, and Euro-Americans of several ranks. It is important to integrate these material finds into the broader history of this subaltern technology. Archaeologists puzzled over the range of pipes they uncovered, including those of terracotta clay—a sharp contrast to the typical white pipe clay of most European manufacture. Terracotta pipes were found near former colonial dwellings where domestic laborers congregated; in one case, in a backyard area where the kitchen, privies, and trash pits were set—a clearly defined subaltern space.9 The cheapest pipes, including those locally made, were accessible to the poorest, who took their moments of respite as luck allowed. Material evidence suggests that local Indigenous people made some of these wares for proximate buyers, with shapes and dimensions modeled on common European forms that would be recognizable to Virginia residents. Other examples, excavated from eighteenth-century King William County, Virginia, were mold-made out of local red clay, a product of settler enterprise, though displaying aesthetic elements thought appealing to Indigenous tobacco users. Colonists took up secondary trades to supplement their income when times were hard, mastering the look and feel of goods aimed at local buyers, perhaps using Indigenous labor as servants or slaves. Christopher Fennell concludes that “archaeological and documentary evidence . . . [support] the interpretation that Chesapeake pipes were a product of English and Native American approaches.”10 Trade, habit, and custom are evident in surviving artifacts, opening wider narratives of subaltern technologies, the agents active in their production, and the varied communities they served.

Tobacco pipes were exceptionally malleable cultural devices that held layered significance, including as part of an imperial apparatus; essential for plebeian hospitality and ceremony, they also became a tool to secure obedience from generations of African men and women on the Middle Passage and in plantation settings. Tobacco was thus re-oriented for African men and women (at least in part) in the transition to enslavement. Barrels of pipes were stocked on ocean-going vessels for the use of sailors and human cargo, as on slave ships.11 In the latter instance, tobacco leaves and a pipe were awarded to the newly enslaved, as well as those embarking on the Atlantic run, in a process described as “seasoning,” a strategy used by ships’ captains to secure compliance.12 Coercive rituals were as central as social ceremonies in the spread of this technology. Pipes for this purpose were also named. The designation of “negro pipes” was not typically employed while onshore in Britain; it is rare, for example, to find this term mentioned in contemporary print sources. However, it was assigned in port records of exports and once laden as cargo. One shipment noted in the Dutch (and then British) colony of Demerara in 1804 included “fine long Dutch and Negro pipes.”13 “Negro pipes” were officially acknowledged when off-loaded in Caribbean ports, differentiated from similar accessories intended for the higher, whiter echelons. “Negro pipes” served as talismans of tobacco’s role in the management of enslaved populations, a denominator that is a further reminder of the power structures by which most tobacco was produced.14

But evidence of Africans’ familiarity with tobacco, including with their own pipes, survives in the form of colonial artifacts recovered from plantation sites, which demonstrate how West African aesthetics also shaped ceramic manufacture and decoration in the Atlantic World.15 In fact, Africans likely had tobacco access in their prison at Cape Coast Castle, Ghana, en route to their enslavement in the Americas. Archaeologists report the “large numbers” of finds recovered in slave holding cells in Cape Coast Castle; as previously stated, giving slaves access to tobacco prior to and during the Middle Passage was routine.16 Among the remnants of fauna, glass beads, and bottles in the female dungeon of Cape Coast Castle were “some forty-eight fragments of smoking pipes of Dutch or English manufacture dating to the period 1670-1790.”17 As Wazi Apoh, James Anquandah, and Seyram Amenyo-Xa observe, “Most striking are the similarities between European material culture found at Cape Coast Castle and European material culture recovered at other global sites of colonialism.”18 In keeping with spiritual beliefs and cultural priorities, the Africans who survived the transit marked their smoking utensils wherever possible, turning these pipes into culturally resonant instruments. Writing about backcountry, colonial Virginia, Ann Smart Martin confirms the agency of Africans once settled in the colonies, citing “the important evidence of independent slave production . . . [including] pipes made of locally available schist,” tools that would be “cut and marked” to make their pipes more aligned with the owner’s aesthetic and spiritual requirements.19 The totality of these interventions cannot be quantified, but the significance of this material agency is immense.

When chance allowed, enslaved Africans also selected material culture that supported their beliefs, including “the appropriation of a common European design element for a sacred [Central African] Bakongo one.”20 Some European-made pipes had designs resonant with Africans, such as the beehive motif of flying insects and other symbols, an instance of which comes from a plantation in the Bahamas where evidence survives of the priorities of a married African man in his fifties, working as a driver. Like other Africans in the Bahamas in the early 1800s, the driver originated on the Atlantic coast of Central Africa, a region where termite hills and flying insects are endowed with spiritual beliefs: “Termites are like the dead in that they fly, like souls and spirits, but live ‘underground’ in a grave like mound.”21 The slave cabin where this man lived yielded an assortment of clay pipe fragments, including a pipe bowl with an elaborate beehive design. Laurie Wilkie observes of the pipe that “like the Bakongo cosmogram, which emphasizes the relationship between life and death, and the interrelationship of each in the life cycle, the tobacco pipe could portray the same juxtaposition between the living and the dead.”22 Perhaps the smoke from a smoldering pipe held associated spirit meanings as well. Rare examples confirm that a few enslaved Africans carried African-style smoking pipes with them during the Middle Passage. This pipe may have been a random choice, picked up in extremis. Or, it could have been on their person, an everyday essential, carried on a journey the lengths of which they could not have guessed.23 Ira Berlin notes the persistence of African aesthetics and ritual among the African enslaved population of the mid-eighteenth-century Chesapeake region. He writes, “The pottery they made, the pipes they smoked, and perhaps most importantly the way they celebrated rites of passage . . . incorporated ancestral Africa into everyday African-American culture."24

- 1For the example of Philip Edwards (1649-1702/3), arising from an excavation in Bristol, see Type BRST 3 and 4 in Sarah Newns, “Appendix 3.”

- 2Dallal, “Tudor Rose,” 212; Gallagher, “Clay Tobacco Pipes” in “The archaeology of the Tolbooth, Broad Street, Stirling,” Scottish Archaeological Journal 30, nos. 1-2 (2008): 134-135; Sharp, “William and John Banks,” 1-6; Gallagher, “Appendix 4, Clay Tobacco Pipes,” 44-45.

- 3Barry Gaulton, “17th and 18th Century Marked Clay Tobacco Pipes from Ferryland, NL,” Heritage Newfoundland & Labrador, last modified May 2017, https://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/pipemarks-introduction.php; P. J. Boon, “Collections,” Dutch Clay Pipes from Gouda, accessed July 8, 2020, http://www.goudapipes.nl/collections/.

- 4ABDUA: 18403, University of Aberdeen Museum.

- 5James Mooney, “The Funeral Customs of Ireland,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 25, no. 128 (1888): 268-271.

- 6Maria Edgeworth, Castle Rackrent, ed. Susan Kubica Howard (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2007), 68. Emphasis in original.

- 7atricia Lysaght, “Hospitality at Wakes and Funerals in Ireland from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century: Some Evidence from the Written Record,” Folklore 114, no. 3 (2003): 410-412.

- 8n the complexities and use of colonial Virginia pipe-making see Anna S. Agbe-Davis, Tobacco, Pipes, and Race in Colonial Virginia: Little Tubes of Mighty Power (New York: Routledge, 2015), 11-32.

- 9Susan L. Henry, “Terra-Cotta Pipes in 17th Century Maryland and Virginia: A Preliminary Study,” Historical Archaeology 13 (1979): 14-37.

- 10Fennell, “Early African America,” 25.

- 11For example, the Fredensborg, a Danish slave ship that made a roundtrip from Copenhagen to West Africa and the Danish West Indies between 1767 and 1768 and the French ships “La Conquerant” and “Fidelity de Diep,” which were captured with four and eight half barrels of tobacco pipes in 1707 and 1708, respectively. Leif Svalesen, The Slave Ship Fredenborg, trans. Pat Shaw and Selena Winsnes (Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2000), 33, 112-114; Records of the High Court of Admiralty (hereafter HCA) 32/55/16, 32/58/14, National Archives, UK (hereafter NA, UK).

- 12Lemire, Global Trade, 226-227. For examples of European ships seized by English privateers and their tobacco pipe cargo see: the Dutch ship Susanna of Middelburg, 1667, HCA 32/4/82, NA, UK; the French ship St John of St Malo, 1667, HCA 32/12/585, NA, UK; the Spanish ship La Conquerante, 1707, HCA 32/55/16, NA, UK; the French ship Fidelity de Diep, 1708, HCA 32/58/14, NA, UK. For English ships lost to privateers with cargoes of tobacco pipes see: the True Love of London, described as “laden with tobacco pipes,” 1672, HCA 32/9/35, NA, UK; the Batchelour, 1703-1704, HCA 32/51/12, NA, UK.

- 13The British seized the Dutch colony of Demerara in 1796, returned it in 1802 with the Peace of Amiens, and then re-seized it the next year with the return of hostilities, finally formally annexing this region as part of the British empire in 1815. For example, see The Royal Gazette (Kingston, Jamaica), April 29, 1780, July 15, 1780; Daily Advertiser (Kingston, Jamaica), January 4, 1790; Essequebo and Demerary Gazette, June 23, 1804, no. 77 and March 17, 1804, no. 64 www.vc.id.au/edg/index.html, Accessed 1 March 2018; Bristol Presentments, May 10, 1803. No. 34; December 8, 1807. Exports from the 30th of Nov. to the 7th of Dec. 1807. No. 48; British Online Archive, https://microform-digital.login.ezproxy.library.ualberta.ca/boa/collections/47/bristol-shipping-records-imports-and-exports-1770-1917?q=%22negro%20pipes%22, Accessed 1 March 2018.

- 14Archaeological excavations in Port Royal, Jamaica recovered over 21,000 clay pipes (complete and fragmentary)—goods that arrived prior to the 1692 earthquake. Georgia L. Fox, “Interpreting Socioeconomic Changes in 17th-Century England and Port Royal, Jamaica, Through Analysis of the Port Royal Kaolin Clay Pipes,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 6, no. 1 (2002): 62.

- 15Matthew C. Emerson, “African Inspirations in a New World Art and Artifact: Decorated Tobacco Pipes from the Chesapeake,” in ‘I, Too Am American’: Archaeological Studies of African American Life, ed. Theresa A Singleton, (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1999); James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life (New York: Anchor Books, 1996).

- 16Jerome S. Handler, “An African-Type Healer/Diviner and His Grave Goods: A Burial from a Plantation Slave Cemetery in Barbados, West Indies,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 1, no. 2 (1997): 112-113; Lemire, Global Trade, 223-227.

- 17Wazi Apoh, James Anquandah, and Seyram Amenyo-Xa, “Shit, Blood, Artifacts, and Tears: Interrogating Visitor Perceptions and Archaeological Residues at Ghana’s Cape Coast Castle Slave Dungeon,” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 7, no. 2 (2018): 121.

- 18Ibid, 121.

- 19Ann Smart Martine, Buying into the World of Goods: Early Consumers in Backcountry Virginia (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2008), 185, 203.

- 20Laurie A. Wilkie, “Culture Bought: Evidence of Creolization in the Consumer Goods of an Enslaved Bahamian Family,” Historical Archaeology 34, no. 3 (2000): 22-23.

- 21Wyatt MacGaffey, Religion and Society in Central Africa (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 263 quoted in Wilkie, “Culture Bought,” 22.

- 22Wilkie, “Culture Bought,” 23.

- 23Lori Lee, “Archaeological Record of the Slave Trade,” in The Historical Encyclopaedia of World Slavery, ed. Junius P. Rodriguez (Oxford: ABC-Clio, 1997), 48; Graeme Henderson, “The Wreck of the Ex-Slaver ‘James Matthews,’” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 12, no. 1 (2008): 48-49.

- 24Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998), 128.

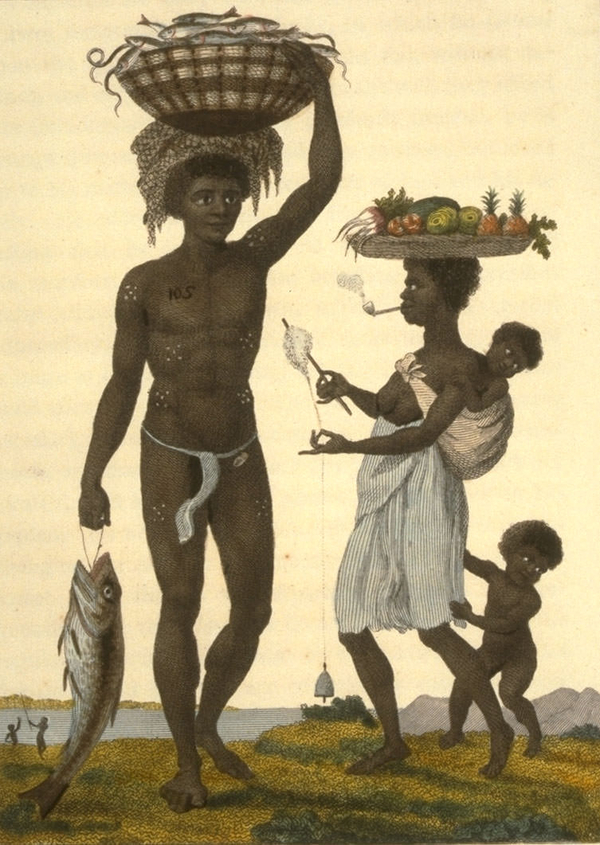

Tobacco pipes facilitated malleable practices across Atlantic World contexts. The cultural plasticity of this tool allowed a broad penetration of this habit, though smokers themselves had different aims in their rituals. Smoke hung in the air of Atlantic colonies, marking the sometimes divergent intents among tobacco users. Janet Schaw, a Scottish visitor to the Caribbean in the mid 1770s, observed tobacco smoke’s unavoidable presence on the main street of the small island of St. Eustatius, a Dutch colony in the Leeward Islands. Schaw reported that “The town consists of one street a mile long, but very narrow and most disagreeable, as every one smokes tobacco, and the whiffs are constantly blown in your face.”1 Schaw had very decided views on British imperial subjects, including the place and space for Whites and Blacks. I only wish that Schaw enumerated the smokers she saw—enslaved and free— and the tasks they were about. The portrayal of an enslaved African family in the Dutch colony of Surinam illuminates their endless labors and the value they found in a pipe (Fig. 11). The placement of the couple and their children in this print allows the artist to capture the ceaseless pace of man and wife: he carrying a weight of fish just caught and she spinning while transporting local fruit and caring for her infant and toddler. The pipe she smokes has the look of a western-made white clay example. We cannot know if her easy smoking comes from tobacco use learned in Africa or her time in this Dutch colony. Did it help her juggle her many roles? While the commonality of this device was set within a manifest imbalance of power, the people of color in these colonies expressed their resistance, agency, and creativity through its use. Pipes were part of their cultural repertoire long before they arrived on the coast of Surinam. The smell of tobacco in this Dutch settlement signified the broad workings of empire at each point around the Atlantic basin.

- 1Janet Schaw, Journal of a Lady of Quality; Being a Narrative of a Journey from Scotland to the West Indies, North Carolina, and Portugal, in the Years 1774 to 1776, ed. Evangeline Walker Andrews (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1921), 136.