It was, after all, the movement of these Penitente crosses across the landscape of New Mexico in local rituals that gave them their fullest spiritual meaning. Founded in the early 1800s by Christianized nontribal native peoples of slave ancestry and other exiled Pueblo Indians, the Penitentes were a lay Catholic brotherhood that emerged in the priestly vacuum created by the withdrawal of the Franciscan order from New Mexico in 1790. The Brotherhood’s rituals centered upon the remembrance of Christ’s Passion, and accordingly emphasized human submission to suffering through rituals of mortification, flagellation, cross-bearing, and reenacted crucifixions. As the Catholic Church began to reassert its presence in the region from the mid-1800s onward, the Penitentes would continue their Holy Week processions, but also sought the privacy of their moradas for their year-round devotions.

The crosses erected outside the morada at Taos were processional crosses, just three of the multitude that dotted the region and were picked up from their bases and carried along on holy days, especially during Holy Week rituals.

Created out of her own physical movements, O’Keeffe’s cross paintings reify that ceremonial context.

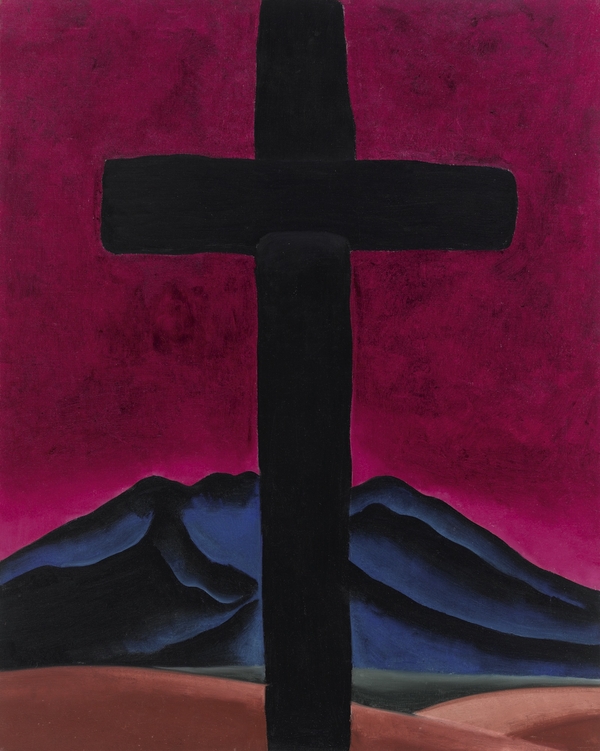

The extreme collapse of the foreground cross and background mountain here and in Black Cross, New Mexico (1929; Art Institute of Chicago, acc. no. 1943.95) further indexes a sense of movement through space, registering both O’Keeffe’s perambulations and the crosses’ processional movements in this landscape. As Robin Kelsey has written regarding Arthur Schott’s U.S.-Mexico boundary surveys from the 1850s, such compact renderings of the landscape, which eschew the full continuity of spatial recession by superimposing foreground elements directly upon background ones, accelerate the viewer’s own visual traversal of pictorial space. O’Keeffe’s black crosses are therefore experiential, physio-optical pictures. Her critics, upon first seeing them, recognized this transcendent quality. New York Times critic Edward Alden Jewell praised how her crosses “pierce[d] through to sheer spiritual experience,” while a writer from the New York Sun declared, “A gallery is no place for [the ‘Crosses’]. [They] ought to be viewed in a church.”

They exude this spiritual, experiential potency because, as Emily Ballew Neff notes, O’Keeffe’s paintings always depict the landscape through the lens of what has happened there.

Indeed, O’Keeffe herself spoke of her endeavors to INSERT IGNORE INTO a picture “the life that has been lived in a place.”

The viewer ought to see her black crosses, then, as marking off a world of human action and pious ceremony; as living, moving objects. As the foreground of Black Cross with Stars and Blue also indicates, this cross stands at a crossroads, a space characterized by the temporary halt and resumption of movement.

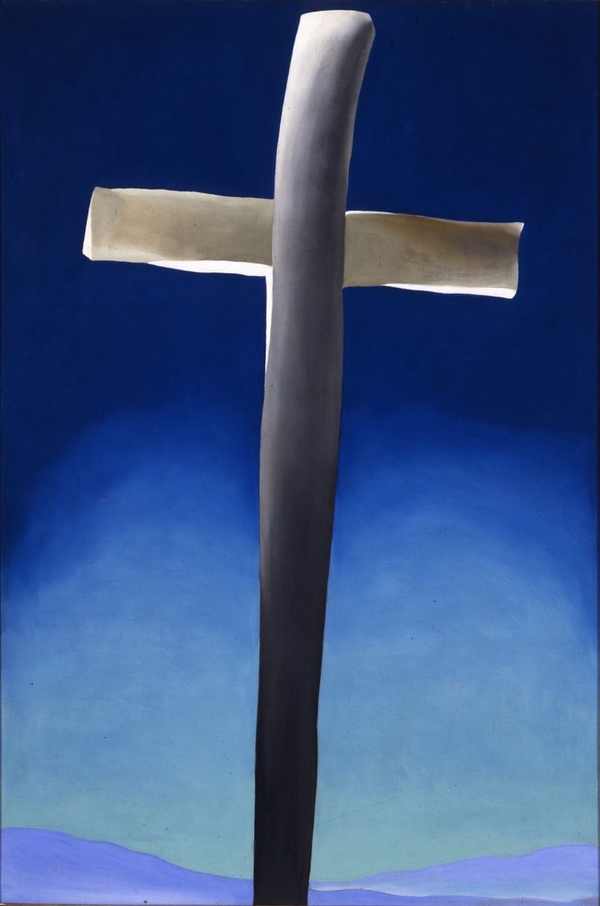

O’Keeffe’s black crosses exist, then, at the cusp of stillness and motion, having merely been paused in the artist’s mind’s-eye and silhouetted against Taos Mountain. Meanwhile, another of her crosses, Grey Cross with Blue (Fig. 4), towers above the horizon, its attenuated, penumbral form leaning forward as if into the viewer’s own space. Like a bowed, swaying cross in a related sketch (1929; Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, acc. no. 1997.06.31)—and unlike the more stationary format and stable viewing position of the black crosses—the Grey Cross looks as if it is being held aloft or even carried at the head of a procession. This may be the same wayside cross to which O’Keeffe referred in a note to Mabel on her return to New Mexico in 1930: “I painted a light cross that I often saw on the road near Alcalde. I looked for it recently but it is not there.”

Perhaps the real grey cross had been picked up and carried off on some procession, resuming its peregrinations in the world.