Cécile Fromont is Professor of the History of Art department at Yale University. She is the author of The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo (University of North Carolina Press and Omohundro Institute, 2014) and Images on a Mission in Early Modern Kongo and Angola (Penn State Press, 2022). She also edited and contributed to the 2019 volume Afro-Catholic Festivals in the Americas: Performance, Representation, and the Making of Black Atlantic Tradition (Penn State Press – Africana Religions Series). Her writing and teaching focus on the visual, material, and religious culture of Africa and Latin America with a special emphasis on the early modern period (ca. 1500-1800), on the Portuguese-speaking Atlantic World, and on the slave trade.

This Essay is in complement to Cécile Fromont’s Images on a Mission in Early Modern Kongo and Angola (University Park: Penn State University Press, 2022). Clicking on the figures in this article will bring readers to galleries containing further images from the works in which they feature.

In my book, Images on a Mission in Early Modern Central Africa, I study for the first time the visual project that Capuchin Franciscan friars devised and implemented in and about central Africa between 1650 and 1750.1 As part of their activities in Kongo and Angola, the friars created dozens of images and wrote hundreds of pages of text in works that they called "practical guides."2 The visual or textual compendia were meant to teach the missionaries that would follow in the veterans’ footsteps about the specificities of central Africa, from its natural environment to its political landscape, to the range of its religious practices from Roman Catholicism to what the friars perceived as heathenry and idolatry.

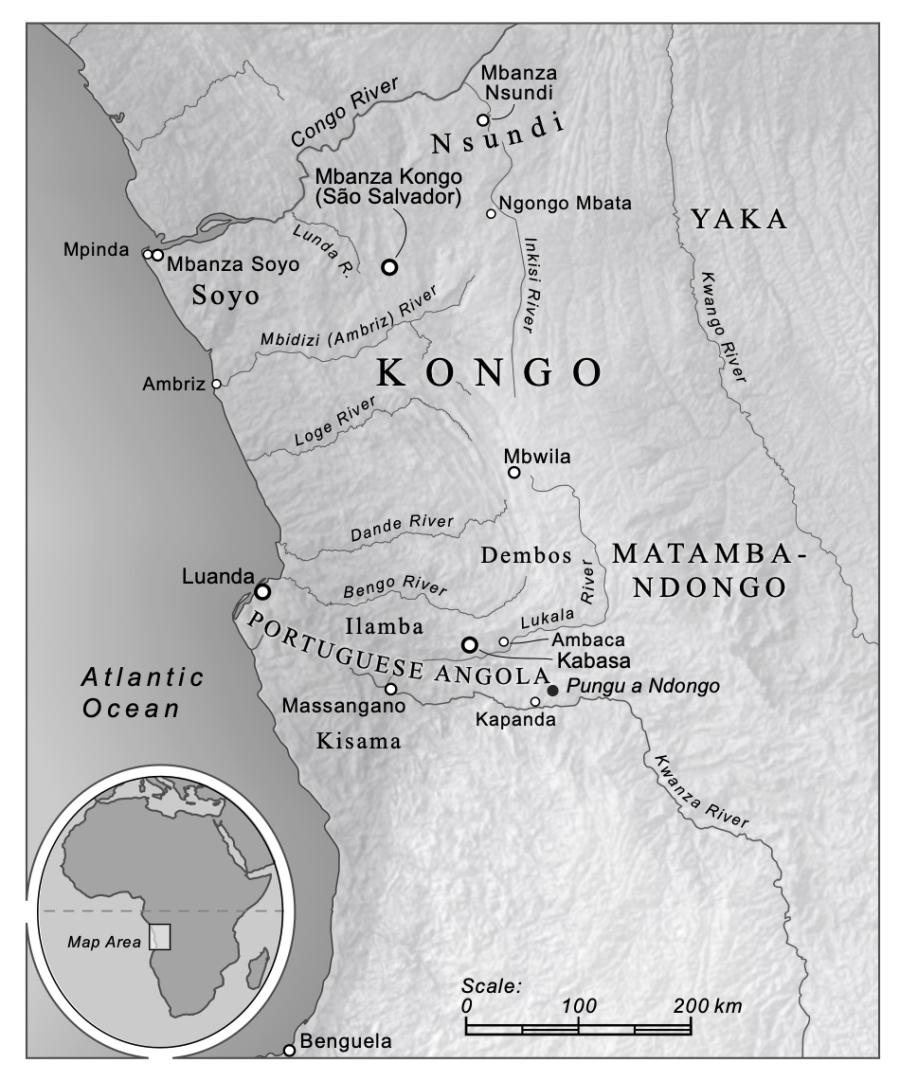

In Images on a Mission, I discuss how the Capuchin didactic images form a unique and exceptionally important corpus that enriches our knowledge of central Africa and dramatically multiplies the European-format visual record about the African continent before 1800. I also demonstrate that the corpus transforms our understanding of early modern global interactions in several ways. First, it brings to the fore the Capuchin missionary project of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that has remained largely unstudied, although it was every bit as broad and ambitious as the contemporaneous, robustly investigated Jesuit and Franciscan apostolic ventures. Further, it highlights a set of spiritual and epistemological interactions between Africans and Europeans unfolding outside of a colonial context. The Capuchins worked in the already Christian kingdom of Kongo as well as in many, for the most part independent, polities such as Matamba, Ndongo, or the Ndembo area in Angola, a toponym the Portuguese coined in the sixteenth century from a local royal title that referred to a region extending over the northern two-thirds of the modern namesake country (Fig. 1).3

- 1Cécile Fromont, Images on a Mission in Early Modern Kongo and Angola (Penn State University Press, 2022).

- 2About these practical guides see Cécile Fromont, “Nature, Culture, and Faith in Seventeenth-Century Kongo and Angola: The Parma Watercolors Texts,” MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2022).

- 3About the geography and history of the region see John K. Thornton, A History of West Central Africa to 1850, vol. 14 (Cambridge University Press, 2020), introduction.

Far from acting as the religious arm of a colonial project, except in the thin enclave of Portuguese Angola, the friars operated in this geography at the demand, and under the supervision of local powers. They had to adhere to the pre-existing organization, rituals, and tenets of the more than century-old church of the Kongo, and worked in both Kongo and Angola alongside central African scholars and specialists who were essential, and in some cases principal, actors leading the knowledge-making and knowledge-gathering enterprise at the core of the corpus they assembled.

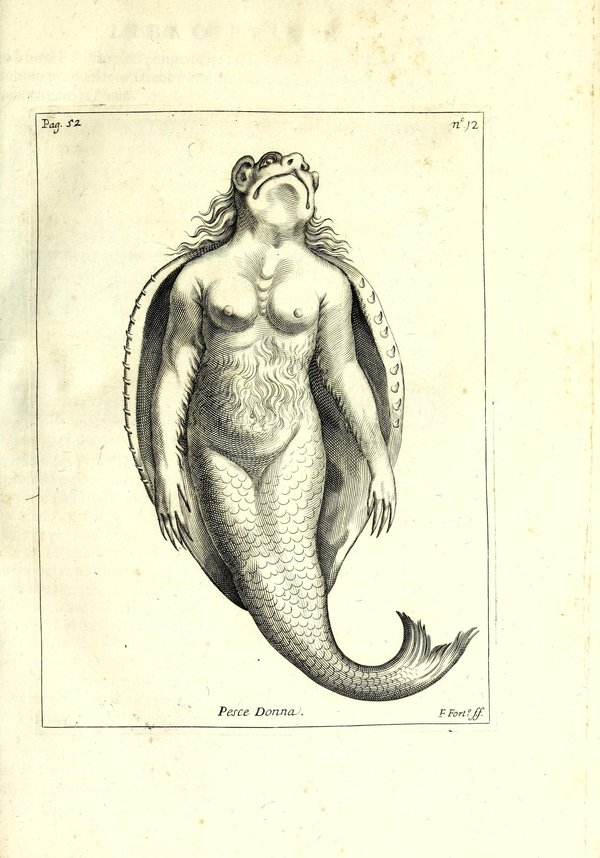

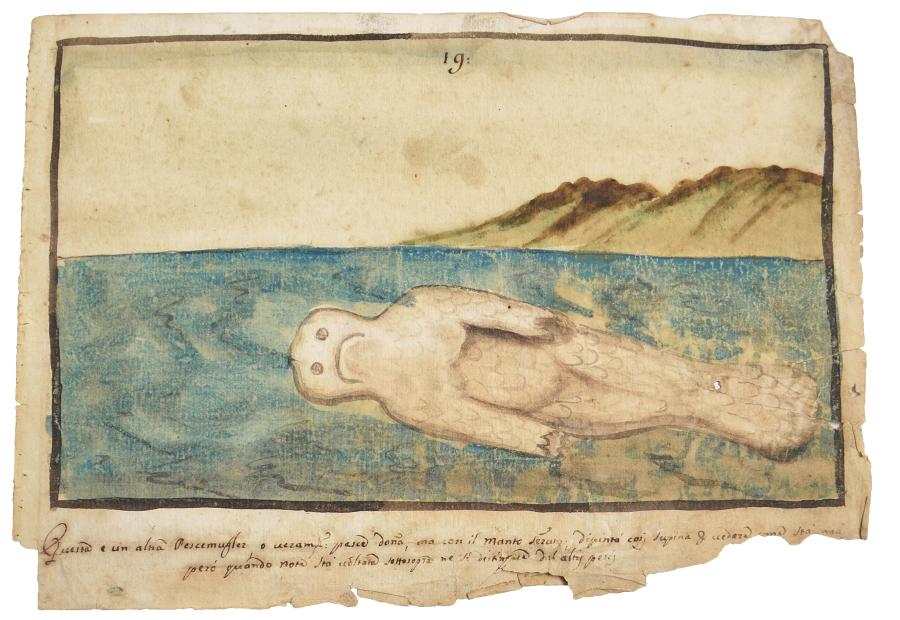

The Capuchin central African vignettes are thus expressions of a discourse about nature, culture, and faith that friars and the people of Kongo and Angola co-constructed in the course of their interactions. They are, in this view, not European conceived and executed pictures of the region and its inhabitants, but pictures from central Africa, molded in the dialogue that unfolded between the friars and central Africans. In analyzing the unique, fraught yet collaborative relationship between friars and central Africans from which the Capuchin images and texts emerged, Images on a Mission probes the mechanics of cross-cultural religious change and knowledge-creation in the early modern period. It analyses the nature, process, and limits of Catholic conversion and the fluid contours of orthodoxy drawn in the confrontations and negotiations unfolding among a heterogeneous cast of European and African priests, local church leaders, devout Christians, apostates, heathens, and cynics. It also enriches our grasp of the cross-cultural dimension of early modern (visual) natural history in offering examples of knowledge honed in the meeting and integration of classical, biblical, and other European written and oral sources with African ideas and modes of experimentation. The page of the Parma Watercolors holding the fantastical manatee pictured as a woman-fish after its Portuguese name and fame of peixe-mulher also recorded, for instance, the anti-hemorrhagic use of the animal’s ribs that friars learned from central African “surgeons” (Fig. 2).

A primary goal of Images on a Mission is to reveal and emphasize the cross-cultural dimension of images such as the Capuchins’ that, though concerned with the extra-European world, are of European form, created for European viewers, and, at least nominally, by European image-makers. To do so, it takes an approach that considers the circumstances of the images’ creation, i.e. the cross-cultural encounters, broadly defined, from which they emerged, as their actual author. This method sheds long overdue light on visual productions such as the Capuchin central African images whose cross-cultural dimension has otherwise remained all but invisible to their original viewers as well as to later scholars. In the Capuchin corpus, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century image-makers did not name or mention the local scholars and interlocutors who shaped the content of their compositions, in effect silencing their contributions. In turn, twentieth- and twenty-first-century scholars have been poorly equipped to recognize and acknowledge cross-cultural interventions in visual documents when their traces are not visible at the level of form or documented in the biography of their maker, or when it has been naturalized to the point of becoming invisible.4 Considering the circumstances of the images’ creation as holding authorial agency allows to lift this double veil. It points to the cross-cultural dialogues that underlay their making and it invites analyses that see them no longer as wholly European images of central Africa, but as images from central Africa and molded by central Africans in dialogue with Europeans.

Most of the watercolors and ink drawings that emerged from the Capuchin central African missions have confounded interpretation and remained unpublished in their own times as well as in ours. Images on a Mission analyzes the reasons these images have been so baffling and the consequences of the challenges they posed to viewers, censors, and editors in the seventeenth century as well as to scholars in the twentieth and twenty-first century. This Essay, however, focuses on the limited number of prints linked to the Capuchin central African images that did see the printing press, principally as part of Friar Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo’s Istorica Descrizione de’ tre regni Congo, Matamba et Angola. Published in Bologna in 1687 after a long and complex publication process, this book remains the most important source for central African history to this day.5 This Essay also addresses related imagery published shortly after in another publication, Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento’s Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell’ Africa meridionale (Napoli, 1692).6

- 4Cécile Fromont, “Penned by Encounter: Visibility and Invisibility of the Cross-Cultural in Images from Early Modern Franciscan Missions in Central Africa and Central México,” Renaissance Quarterly 75, no. 4 (2022): 1221-1265; Carolyn Dean and Dana Leibsohn, “Hybridity and Its Discontents: Considering Visual Culture in Colonial Spanish America,” Colonial Latin American Review 12, no. 1 (2003): 5-35.

- 5Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi and Fortunato Alamandini, Istorica descrizione de’ tre regni Congo, Matamba et Angola sitvati nell' Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni apostoliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini (Bologna: Giacomo Monti, 1687). About the publication process see Francisco Leite de Faria, “João António Cavazzi: a sua obra e a sua vida,” in Descrição histórica dos três reinos do Congo, Matamba e Angola, ed. Graciano Maria de Leguzzano (Lisboa: Junta de Investigações do Ultramar, 1965).

- 6Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento and Angelo Piccardo, Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell’ Africa meridionale, fatto dal P. Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento . . . Continente variati clima, arie, animali, fiumi, frutti, vestimenti con proprie figure, diuersita di costumi, e di viueri per l’vso humano (Napoli: Per F. Mollo, 1692).

Cavazzi’s Istorica descrizione

Friar Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, a native of the region of Modena, served as a missionary in central Africa, principally in the lands of queen Njinga, between 1654 and 1667. He had just returned to Italy after a long journey through Brazil when, in 1669, the cardinals of the Propaganda Fide, the papal institution for the propagation of the faith, commissioned from him a history of the Capuchin mission to central Africa. His long experience in the region and his reputation as a prolific writer and image-maker made him a good candidate for the task. He immediately set to work. In addition to the documents he had brought back with him from Angola, he consulted the Roman archives, the meager published material on the region, and the writings of his fellow friars.7 He soon produced a manuscript that, in 1671, failed to obtain the Propaganda Fide’s approval for its publication due to the cost of printing such a lengthy book. When Cavazzi set off for his second stay in central Africa in 1673, he left his book in the hands of his brother in religion, Bonaventura da Montecuccolo, who was to pursue printing in Bologna with an alternate source of funding. The project moved forward until the text and images that Cavazzi had commissioned from friar Paolo da Lorena met the opposition of the censors because of the miracles they described. The manuscript was eventually entrusted to Fortunato Alamandini da Bologna, a Capuchin who never travelled to central Africa, for editing in 1678. After years of revision and further review the book was approved for publication in 1684 and finally published in 1687.8

- 7Texts published before Cavazzi’s writing of the Istorica descrizione include the Capuchin volumes Antonio da Gaeta and Francesco Maria Gioia, La maravigliosa conversione alla santa fede di Cristo della regina Singa e del svo regno di Matamba nell’Africa meridionale, descritta con historico stile (Napoli: G. Passaro, 1669); Dionigi de Carli da Piacenza and Michael Angelo de Guattini Reggio, Viaggio del P. Dionigi de’ Carli da Piacenza e del P. Michel Angelo De’Guattini da Reggio Capuccini, Predicatori e missionari Apostolici nel Regno del Congo (Reggio: Prospero Vedrotti, 1671); and Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta, Relatione del reame di Congo et delle circonvicine contrade, tratta dalli scritti & ragionamenti di Odoardo Lopez, Portoghese (Roma: Appresso B. Grassi, 1591).

- 8About the history of publication of the book see Faria, “João António Cavazzi,” xxv-xxxi.

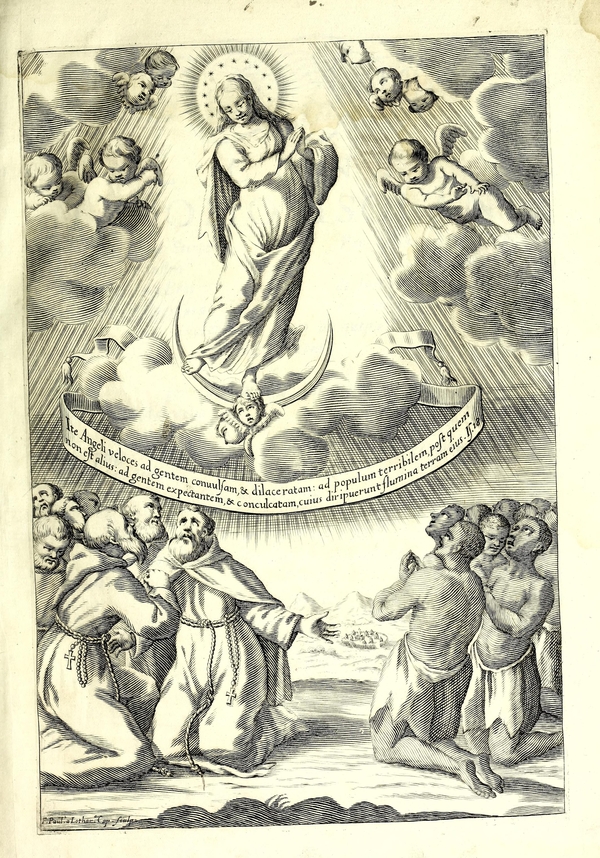

The final version of the book includes fifty-one copper plate engravings and etchings. Most of the prints are the creation of Paolo da Lorena from Cavazzi’s commission of the early 1670s, including the frontispiece signed “F. Paul.s a Lothar.a Cap. Sculp” (Fig. 3). Fortunato Alamandini conceived and proudly signed eight others “F. Fort°. f.f.” as corrective to what he deemed the “weak” images of friar Paolo, which he had hoped to replace altogether, but was not able to do so for lack of funds (see for example Fig. 4).9

- 9Cavazzi and Alamandini, Istorica descrizione de' tre regni Congo, Matamba et Angola sitvati nell’ Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni apostoliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini, n.p., 3rd page of foreword. See table in Fromont, Images on a Mission, 26.

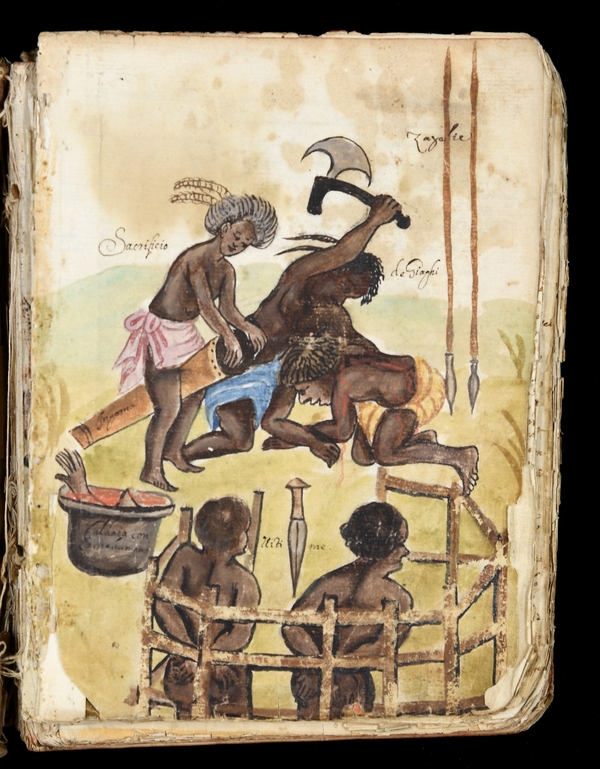

Most of the images in Cavazzi’s Istorica descrizione, whether designed by Paolo da Lorena and Cavazzi, or recreated by Alamandini, have deep roots in the corpus of didactic Capuchin manuscripts, whose format and style many of them share. Only fifteen derive entirely or in part from paintings that Cavazzi composed in the 1660s for an earlier work which was not one of the practical guides, the Missione Evangelica also known as the Araldi Manuscript, covering similar topics as the Istorica descrizione (compare for instance Fig. 5 & Fig. 6).10

- 10Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Missione Evangelica al Regno del Congo: Araldi Manuscript, Biblioteca Estense (Modena, 1665-1668). About the Araldi manuscript see Giuseppe Pistoni, “I manoscritti ‘Araldi’ di padre Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo,” Atti e momorie della Academia Nazionale di Scienze, Leterre e Arti di Modena 6, no. 11 (1969); Ezio Bassani and Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi, Un Cappuccino nell'Africa nera del Seicento: i disegni dei Manoscritti Araldi del Padre Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi da Montecuccolo, Quaderni Poro, 4 (Milano: Associazione “Poro,” 1987), John Kelly Thornton, “Translation of the Araldi Manuscript,” (n.d.).

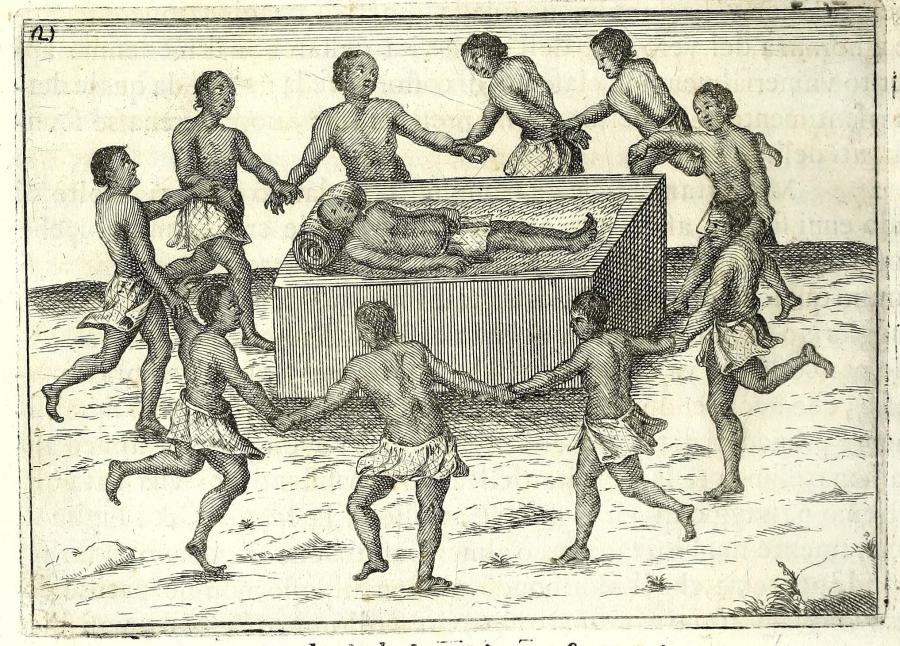

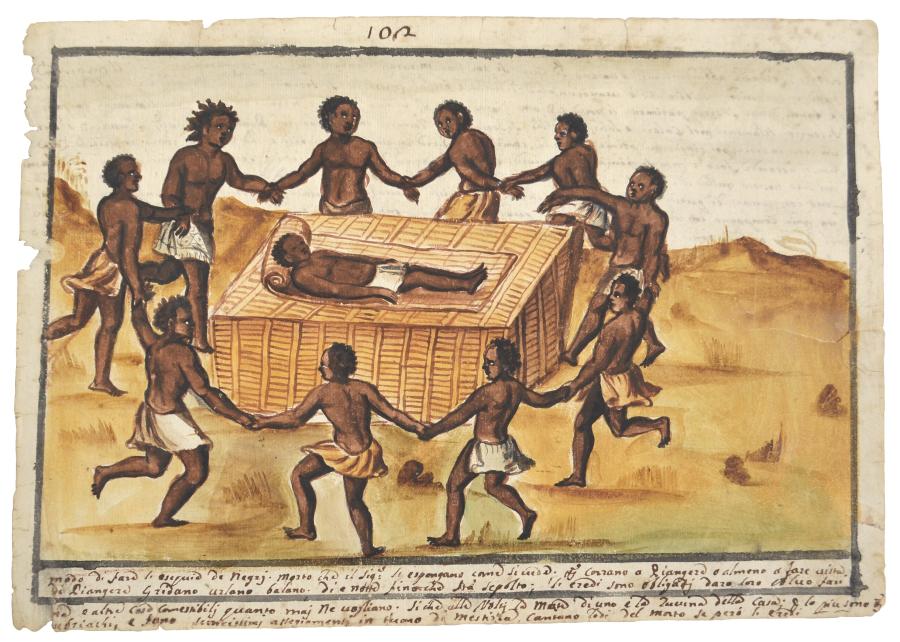

Thirty-three, however, are especially close to one of the didactic manuscripts, the Parma Watercolors created circa 1663-1690.11 The relationship between the two is not directly that of original and copy, but rather one of belonging to a common visual milieu, likely through the existence of a third, common source, until now unidentified and likely no longer extant. The prints and watercolors present to their viewers almost identical scenes, such as that of a funeral ceremony (Figs. 7 & 8) or a manatee, the latter also featuring in Merolla’s Breve . . . relatione, discussed below (Figs. 2, 9-11).12

Fig. 10 "Pesce Donna di fiume" (River Woman Fish) in Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento and Angelo Piccardo, Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell' Africa meridionale (Napoli: Per F. Mollo, 1692), engraving, 5.9" x 3.7" (15 × 9.5 cm) (plate mark), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The image network in which Cavazzi’s Istorica Descrizione participated also included visual material outside of the Capuchin orbit. Seven of the designs are connected to Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta’s earlier and very successful volume on central Africa, the 1591 Relatione del reame del Congo et delle circonvicine contrade. The Relatione was an edition by Italian cosmographer Pigafetta of the eyewitness testimony about central Africa of Duarte Lopes, a Portuguese merchant whom the king of Kongo made his ambassador to the papacy in the late sixteenth century (Figs. 12 & 13).13 The richly illustrated volume received much attention from contemporary viewers and was translated by the de Bry family of publishers and engravers into Latin and German later in the decade, with additional prints.14 Copies of the de Bry volumes were in Luanda at the time Cavazzi worked on his manuscripts.15

- 13Lopes and Pigafetta, Relatione del reame di Congo.

- 14Duarte Lopes, and Filippo Pigafetta, Regnvm Congo hoc est Warhaffte vnd Eigentliche Beschreibung deß Königreichs Congo in Africa, vnd deren angrentzenden Länder darinnen der Inwohner Glaub, Leben, Sitten vnd Kleydung . . . angezeigt wirdt (Frankfurt am Main: de Bry, 1597); Duarte Lopes, Regnvm Congo, hoc est, Vera descriptio regni Africani: qvod tam ab incolis qvam Lvsitanis Congus appellatur, trans. Filippo Pigafetta (Frankfurt am Main: Excudebat Wolffgangus Richter, 1598).

- 15Fromont, Images on a Mission, 445.

Fig. 13 "Modo di far Viaggio & correr la posta (Mode of traveling and journeying)" in Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta, Relatione del reame di Congo et delle circonvicine contrade, tratta dalli scritti & ragionamenti di Odoardo Lopez, Portoghese (Rome: Appresso B. Grassi, 1591). Natale Bonifacio, 1591, 8.3" x 11.6" (21 × 29.4 cm) (plate mark), Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

Merolla’s Relatione

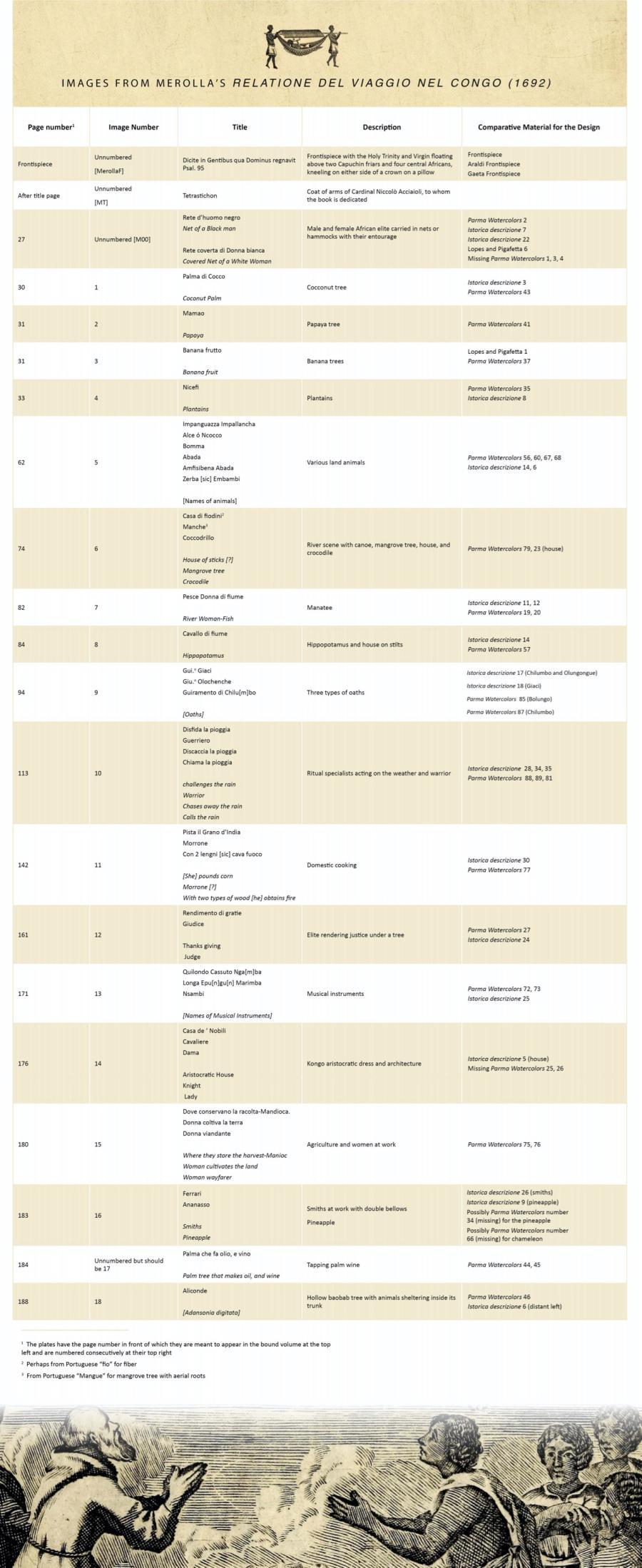

The relation of Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento’s travels to central Africa published in Naples in 1692 belongs to the same visual milieu that produced the prints in the Istorica descrizione. Its nineteen copper plates parallel and complement the prints and paintings in the Istorica descrizione and the Parma Watercolors. The volume, titled Breve, e Succinta Relatione del Viaggio nel Regno di Congo retells Merolla’s activities and experiences in Kongo and Angola between 1683 and 1688 as collected and written down by Angelo Piccardo da Napoli from oral interviews with the missionary after his return to Naples in 1689.16 No information about the commission and production of the copper plates included in the rapidly published volume has emerged so far. It is clear, however, that they share strong kinship with both the Istorica Descrizione and the Parma Watercolors. Merolla’s plates would have been created shortly after the publication of the former and the composition of the latter. The text, moreover, makes many direct or indirect references to the Istorica Descrizione, the publication of which received much attention. In 1690, a second edition of the Istorica descrizione, first published in Bologna in 1687, appeared in Milan, with copper plates copied closely from the first edition. This later, more modest version presented the vignettes bound between pages of text on short strips of paper. The rectangular illustrations were etched several to one large sheet of paper, and then cut into individual images.17 This was the first of many reeditions in several languages.18

- 16José Sarzi Amade, “Réédition, contextualisation et analyse de la Breve e Succinta Relatione del Viaggio nel Regno di Congo [. . .](1692) de Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento,” (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Aix-Marseille, 2016).

- 17Giovanni Antonio Cavazzi et al., Istorica descrittione de’ tre regni Congo, Matamba, et Angola: situati nell’Etiopia inferiore occidentale e delle missioni apostoliche esercitateui da religiosi Capuccini (Milan: Nelle Stampe dell’Agnelli, 1690).

- 18See Edouard d'Alençon, “Essai de Bibliographie Capucino-Congolaise,” Neerlandia Franciscana 1, no. 1 (1914): 262-265.

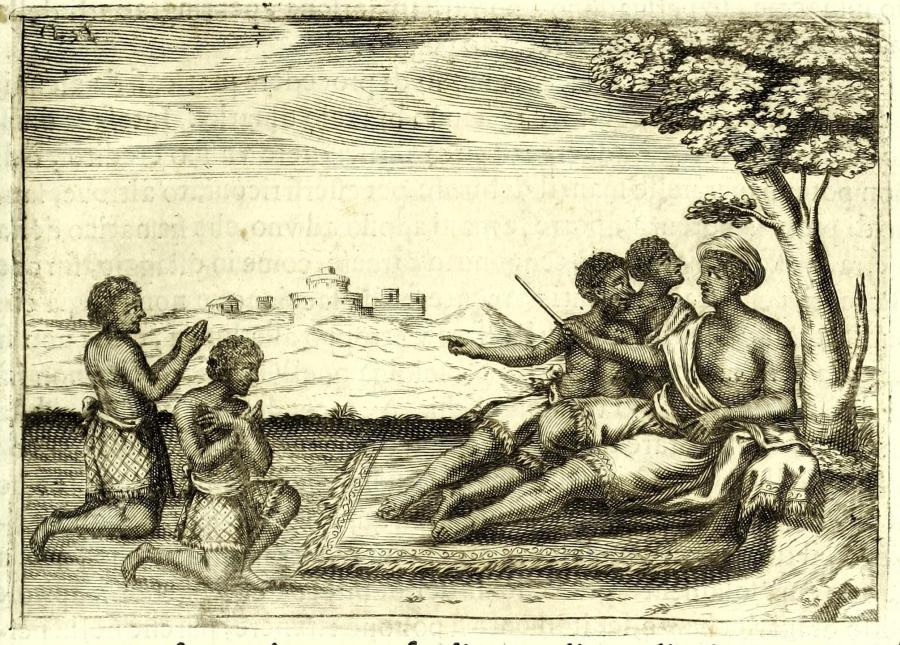

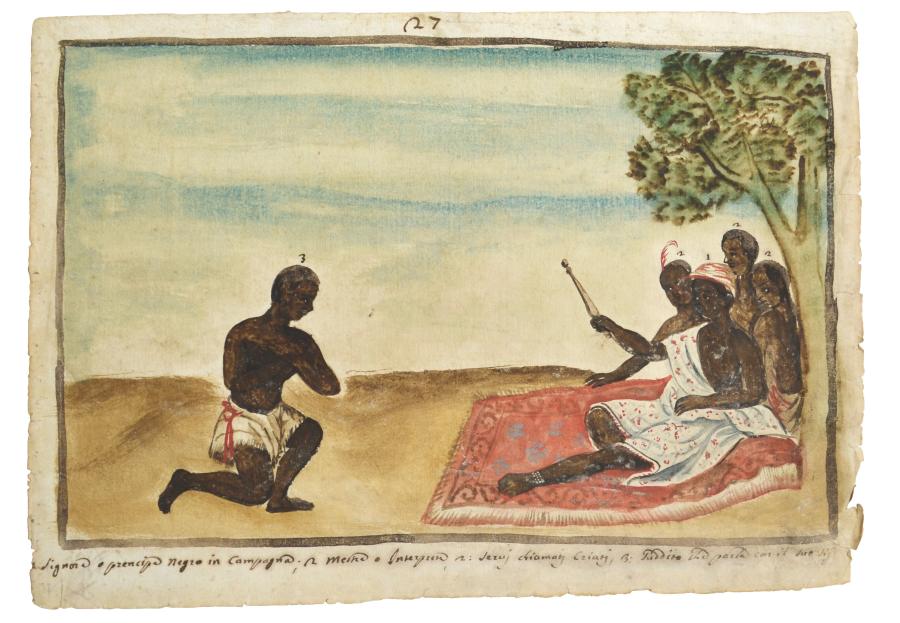

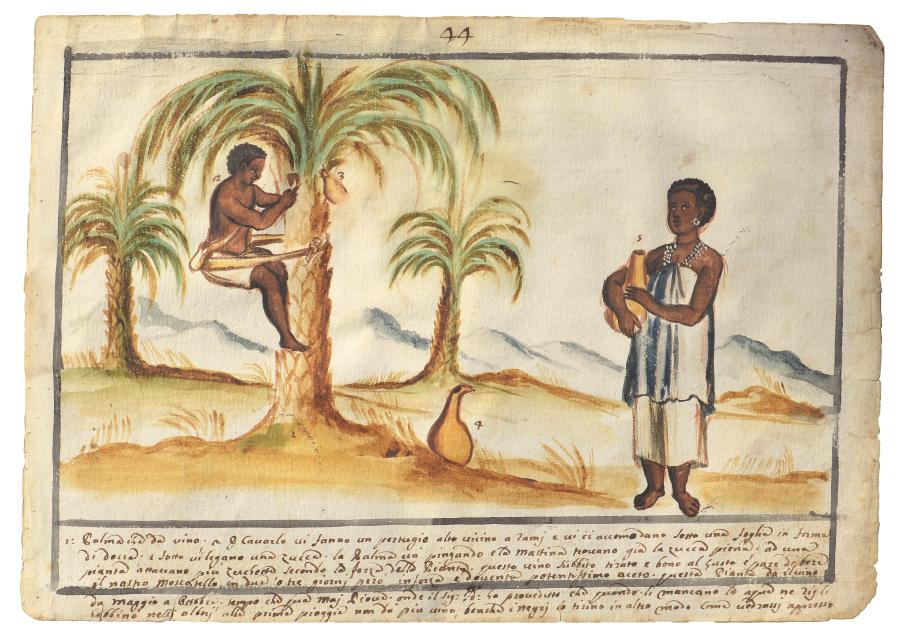

As outlined in table 2, some of the prints in Merolla have precedents in both the Cavazzi prints and the Parma Watercolors. Others have links to only one or the other of the works. Consider for example the scene of justice under the tree in Merolla’s plate 12 (Fig. 14) alongside the Istorica descrizione’s plate 24 (Fig. 15) , or the Parma Watercolors 27 (Fig. 16) While the three scenes of justice closely mirror one another, the tapping of palm wine in number 17 in the sequence (Fig. 17), is echoed, distantly, in the Parma Watercolors 44 (Fig. 18) but does not feature in the Istorica descrizione.

Fig. 17 "Palma che fa olio, e vino" (Palm tree that makes oil, wine) in Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento and Angelo Piccardo, Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell' Africa meridionale (Napoli: Per F. Mollo, 1692), engraving, 5.9" x 3.7" (15 × 9.5 cm) (plate mark), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

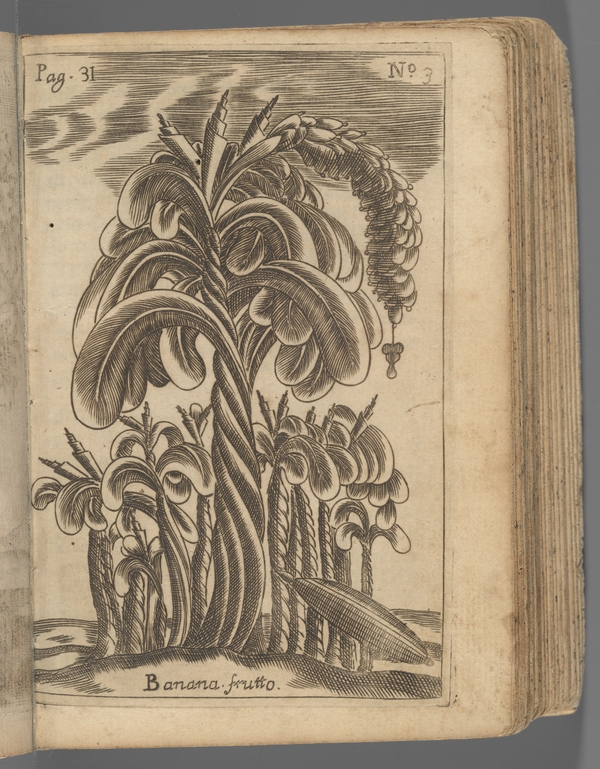

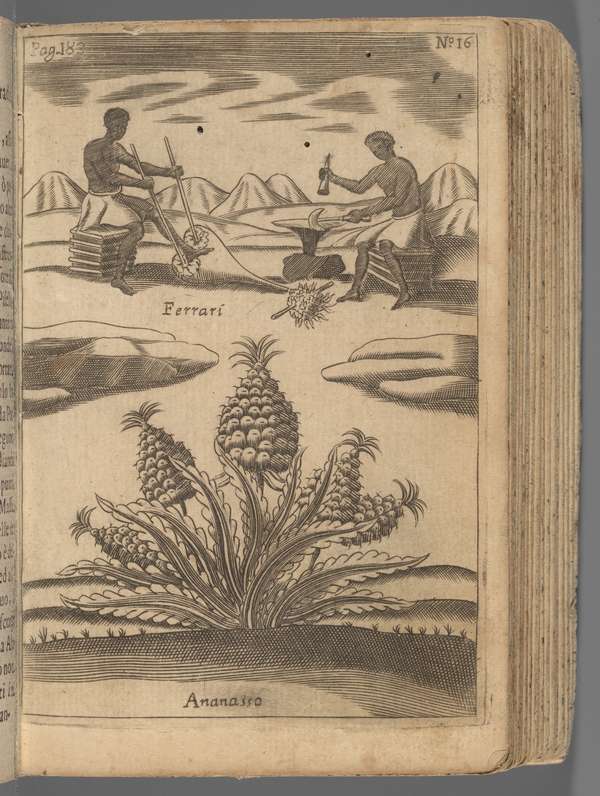

Others still have parallels in neither. Some have sources outside of the Capuchin central African realm, such as the banana tree in plate 3 (Fig. 19), which is close to the one in Lopes and Pigafetta(Fig. 20). Most of the vignettes without direct comparanda, however, follow templates that would easily fit within the missing pages of the Parma Watercolors, which, in their current state of conservation include 67 folios labelled from numbers 2 to 104, with lacunae. For example, the depiction of blacksmithing at the top of print 16 (Fig. 21) would have found its place alongside the Parma Watercolors depicting work and craft such as agriculture, folio 76r, cooking, folio 77r, or weaving, folio 79r. The compound at the top of print 14 (Fig. 22) would fit alongside the series on architecture starting with folios 23r and 24r, but missing two folios, numbers 25 and 26. The aristocratic man and woman at the bottom of the same print in Merolla, in turn, would insert itself well as the missing folio 69r preceding a similar representation of dress in folio 70r.

Fig. 20 "Spetie di palma, che fa la seta" (Type of palm tree that makes silk) in Duarte Lopes and Filippo Pigafetta, Relatione del reame di Congo et delle circonvicine contrade, tratta dalli scritti & ragionamenti di Odoardo Lopez, Portoghese (Rome: Appresso B. Grassi, 1591). Natale Bonifacio (attr.), 1591, Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

Fig. 21 "Ferrari. Ananasso" (Smiths. Pineapple) in Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento and Angelo Piccardo, Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell' Africa meridionale (Napoli: Per F. Mollo, 1692), engraving, 5.9" x 3.7" (15 × 9.5 cm) (plate mark), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Fig. 22 "Casa de Nobili. Cavaliere. Dama" (Aristocratic House. Knight. Lady) in Girolamo Merolla da Sorrento and Angelo Piccardo, Breve, e svccinta relatione del viaggio nel regno di Congo nell' Africa meridionale (Napoli: Per F. Mollo, 1692), engraving, 5.9" x 3.7" (15 × 9.5 cm) (plate mark), Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Notably, none of the prints in Merolla are linked to the Araldi manuscript or to vignettes in the Istorica descrizione inspired by it. This is a telling detail that suggests that Merolla or his editor Piccardo did not rely only or even principally on Cavazzi’s published tome in the creation of the prints. Rather, Merolla’s illustration program points to its origins in another set of visual models, linked to the Parma Watercolors. It thus stands as a significant piece in the visual jigsaw puzzle of the Capuchin visual production linked to their missions in Kongo and Angola.

Tables

The two tables below describe the interconnections between Cavazzi’s Istorica descrizione, Merolla’s Relatione, and other visual sources in the Capuchin visual corpus and beyond. Visual comparisons can be accessed by clicking on the image number. The images presented in this Essay are the best available at the time of publication, though not always completely satisfactory. The binding for Merolla’s Relatione is particularly tight in most extant copies, which makes scans or photographs of its illustrations challenging to produce. This issue has been compounded by the ongoing limitations on new imaging due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Essay assembled nonetheless serves its purpose of assembling, presenting, organizing, and inviting further attention to this important and understudied corpus of images.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2022.11

1. Cécile Fromont, "Depicting Kongo and Angola in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.11.

Fromont, Cécile. "Depicting Kongo and Angola in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 1 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2022.11.