A special issue guest edited by Kambiz GhaneaBassiri and Anna Bigelow.

Volume 6: Issue 2 Material Islam

Introduction to the Special Issue: Material Islam

Introduction to the Special Issue: Material Islam

Anna Bigelow and Kambiz GhaneaBassiri introduce this special issue of MAVCOR Journal devoted to Material Islam. It explores devotional objects, the Islamic sensorium, the book as a material object, the Muslim body, and the various roles of the mosque as a social, political, and spiritual space. Taken together, its varied essays demonstrate an incredibly wide-ranging, rich, and exciting arena of study.

In Conversation with Christiane Gruber on Material Islamic Studies

In Conversation with Christiane Gruber on Material Islamic Studies

Kambiz GhaneaBassiri and Anna Bigelow speak with Christiane Gruber about changes and growth in field of Material Islam, new arenas of inquiry, and their hopes for further interdisciplinary scholarship.

Ablution Socks: The Logic of Market Capitalism and Its Limits

Ablution Socks: The Logic of Market Capitalism and Its Limits

The marketing of “wudhu socks" provides an interesting window onto how the forces of consumer capitalism in twenty-first-century America are brought to bear on a centuries-old hermeneutical, legal, and theological tradition in Islam that has long conceptualized purity through embodiment and objects.

The Transcontinental Genealogy of the Afro-Brazilian Mosque

The Transcontinental Genealogy of the Afro-Brazilian Mosque

This article examines the genealogy of Afro-Brazilian mosques, answering some of the most immediate and puzzling questions that they force all who see them to ask. The answers to these questions demonstrate the fluidity of categories such as European, African, Islamic, and Christian, and how West African Muslims effectively drew on an architectural vocabulary with connections to three continents to forge an emergent cosmopolitan identity.

Senses of Belonging: Materiality, Embodiment, and Attunement at Sufi Shrines in India

In exploring the multiple modalities of Muslim belonging and unbelonging in India, the arenas in which Muslims and non-Muslims interact, especially at shared holy places, are extremely illuminating locales. This essay explores the ways in which material and somatic forms of interreligious encounter at a Sufi dargah (درگاہ), or tomb shrine, in Bengalaru (Bangalore) exemplify everyday as well as spectacular practices of shared piety that also reimagine the possibility of collective belonging in a time of precarity.

Senses of Belonging: Materiality, Embodiment, and Attunement at Sufi Shrines in India

In exploring the multiple modalities of Muslim belonging and unbelonging in India, the arenas in which Muslims and non-Muslims interact, especially at shared holy places, are extremely illuminating locales. This essay explores the ways in which material and somatic forms of interreligious encounter at a Sufi dargah (درگاہ), or tomb shrine, in Bengalaru (Bangalore) exemplify everyday as well as spectacular practices of shared piety that also reimagine the possibility of collective belonging in a time of precarity.

Bībī kā ʿAlam

Bībī kā ʿAlam

The Bībī kā ʿalam, as it is popularly known, occupies a special, sacred class of ʿalams for the Hyderabadi Shiʿa. Containing Fatimah’s funerary plank, is a reliquary ʿalam and, while Hyderabad is distinctive for the extraordinary number of relics it possesses that are associated with the Imams and Ahl-e Bait, very few connect to Shiʿi women saints.

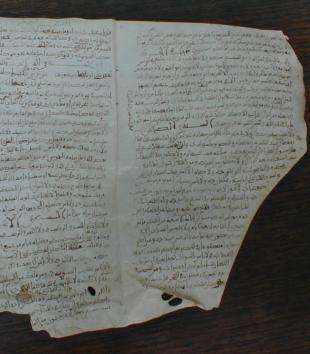

A tenth-century Islamic manuscript from Kairouan, Tunisia

A tenth-century Islamic manuscript from Kairouan, Tunisia

A parchment bifolio from the Kairouan collection presents a mystery. But like pottery in an archeological dig, this fragment is in situ, and clues to the identity of the author, the text, and the community of scholars that wrote and preserved it, are found in the rich context of this unique collection. Together, these manuscripts bear witness to a fascinating history of literary and cultural production, not only in North Africa, but in the broader Islamic world of the ninth and tenth century.

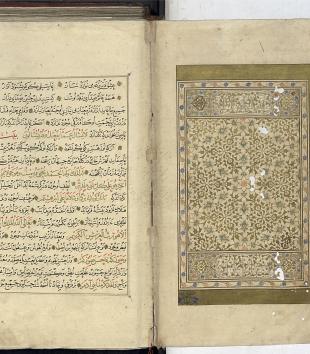

Adorning the King of Islam: Weaving and Unraveling History in Astarabadi’s Feasting and Fighting

Adorning the King of Islam: Weaving and Unraveling History in Astarabadi’s Feasting and Fighting

This article traces a fourteenth-century Persian history from Anatolia, Bazm wa Razm (Feasting and Fighting), written by ʿAzīz al-Dīn Astarābādī, from its presentation copy to its various recensions down to the modern period, examining how each era visually refigures this textual manifestation of its original patron, Burhān al-Dīn Aḥmad (r. 783-800 AH/1381-1398 CE), for a new purpose.

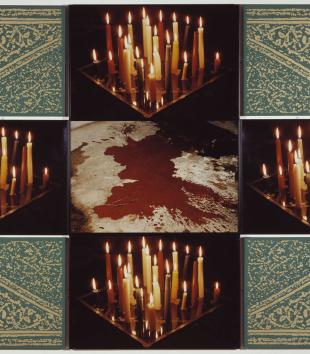

Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah

Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah

Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah is noteworthy as the first work by the Karachi-born, London-based artist to enter the collection of Britain’s Tate Gallery in 1995. Bismullah deploys strategies of juxtaposition, disjunction, and doubling to combine visual imagery that references religion, empire, art history, and the artist’s personal biography. Through its montage tactics Bismullah not only maps the binaries of self and other that structure colonial discourse within and beyond the artistic field, but also recontextualizes these signifiers.

Hikmet Barutçugil's Hüdayi Yolu

Hikmet Barutçugil's Hüdayi Yolu

Hüdayi Yolu represents a modern artist’s loving depiction of his hometown and neighborhood, an homage to a local Sufi saint, the romanticized communal memory of Istanbul as an Ottoman metropolis, and Barutçugil’s approach to “Sufi” art.

On the Material and Social Conditions of Khalwa in Medieval Sufism

On the Material and Social Conditions of Khalwa in Medieval Sufism

Ubiquitous across the medieval Islamic world, khalwa is the practice of self-isolation, typically in a small cell, in order to focus on pious devotions. This article offers one possible approach to theorizing the heterogenous elements of khalwa coherently by insisting that we take the material and the social as seriously as we do the human and the spiritual.

Ayat Al Kursi Round

Ayat Al Kursi Round

Crowned by the word “Allah,” a dense piece of Arabic calligraphy carved out of stainless steel wraps around an embellished center. The text is the ayat al-kursī, or “The Throne Verse,” a portion of the Qur’an (2:256) often recited before sleep or travel because of its reputation for spiritual and physical protection. While the Illinois-based company Modern Wall Art produces the above “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” at least six other businesses manufacture their own ayat al-kursī pieces in the same circular visual style. These pieces of Islamic decor appeal to different tastes in spite of the repetitiveness of their visual content. By attending to the specific production method and branding of “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” we can identify how the materialization of God’s words in wall art entangles Islamic ethics and the aesthetics of class formation.