Kylie Gilchrist is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History and Visual Studies at the University of Manchester.

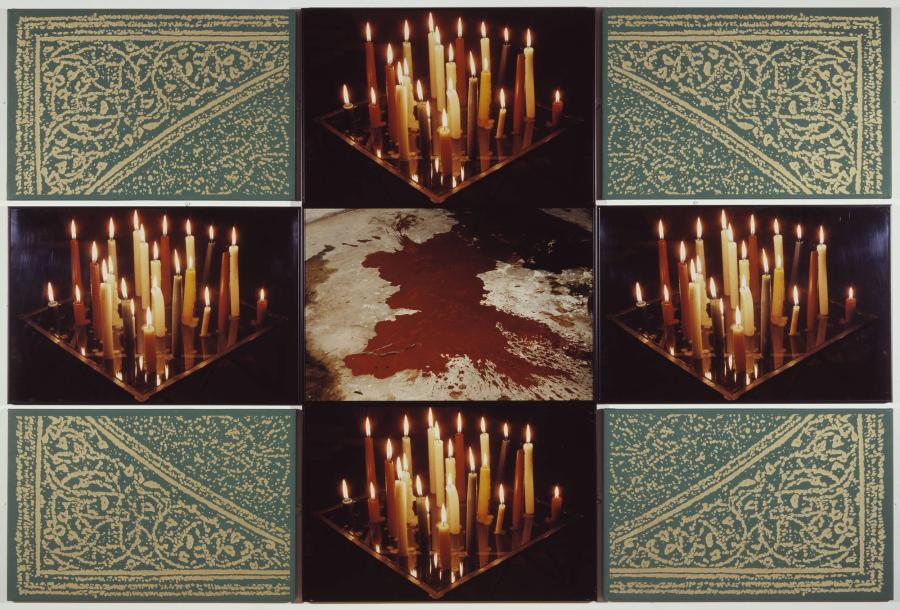

Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah (Fig. 1) is noteworthy as the first work by the Karachi-born, London-based artist to enter the collection of Britain’s Tate Gallery in 1995. Part of Araeen’s “Cruciform” series of the 1980s and 1990s, Bismullah is a wall-mounted, mixed-media construction assembled from nine rectangular panels.1 At each of the work’s four corners sit canvases painted a verdant green and silk-screened with a delicate golden patterning that recalls vegetal and floral motifs common in Islamic architecture. The green panels are disconnected slightly from the work’s inner components, and the white gallery wall appears in the gaps like fissures and borders internal to the work.2 Set between the green panels are four identical photographs of candles, formed in the shape of a cross. The candles are set on a piece of glass that, on close inspection, appears to sit atop one of Araeen’s own artworks: the three-dimensional, open-faced “structural cubes” that the artist conceptualized in the mid-1960s. At the work’s center is a photograph of a splash of blood, closely cropped to omit explanatory information. The vermillion shape is Rorschach-like, encouraging a play of associations.

Araeen created Bismullah at the tail end of the 1980s—a decade of considerable socio-political and cultural change in Britain. Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government inaugurated a period of neoliberal governance and re-ignited imperialist ambitions indexed by the 1982 Falkland Islands War—developments paralleled across the Atlantic under Ronald Reagan’s administration and its aggressively interventionist foreign policy. Domestically, the UK experienced social unrest sparked by racist violence and countermanding anti-racist struggles, motivating public policies aimed towards multiculturalist integration.3 These events reverberated in artistic practice. While mainstream and commercial art worlds celebrated a conservative return to painting, a resurgent radicality animated the work of diaspora artists who sought to contest the sedimented edifices of a narrowly Eurocentric artistic canon.4

Within this artistic field, montage was an exemplary artistic tactic.5 A strategy of juxtaposition and recombination aiming to reshape perception, montage practices reprised the experimental and interventionist legacies of the twentieth-century vanguards. Araeen had deployed montage towards politicized ends since the early 1970s, perhaps most famously in For Oluwale (1971-3/5), which combined a variety of printed media in an acidulous response to the 1969 murder of David Oluwale by the Leeds police. In the 1980s, as Kobena Mercer has argued, “cut and mix” strategies also appeared prominently in a younger generation of British-born artists including Eddie Chambers, Maud Sulter, and the Black Audio Film Collective. These artistic techniques were, he argues, a key means of interrupting and reworking systems of signification shaped by the ongoing legacies of empire and colonial racism.6 Mercer’s analysis can be extended to consider Bismullah, which deploys strategies of juxtaposition, disjunction, and doubling to combine visual imagery that references religion, empire, art history, and the artist’s personal biography. Through its montage tactics Bismullah not only maps the binaries of self and other that structure colonial discourse within and beyond the artistic field, but also recontextualizes these signifiers.

Bismullah signals its intervention through its title—a play on the Islamic phrase bismi’llāh. Recalling the Dadist and surrealist propensity for puns, Araeen shifts its meaning from “in the name of God” to “in the name of the priest (mullā)” through a slight orthographic intervention. To Western viewers unaware of the word play’s significance, the title might evoke media representations of Islam on the stage of global politics during the period of the Cruciform series, indexed by the Iranian Revolution of 1978–9 as well as the “Islamicization” program under General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq’s decade of autocratic rule in Pakistan (1978–88). Stereotypes of Islamic “extremism” and supposed incompatibility with Western liberal democracy intensified, shortly after Bismullah’s creation, with the publication of Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses in September 1988, generating controversy that reached famously heated proportions in early 1989.7 Yet, as the artist has noted, the title’s reference to priesthood points to the structure of religious authority in Christianity—an association reinforced by the cruciform shape organizing the candle photographs. Reversing the mediatic gaze that framed Islam as a particularly political or politicized religion, Bismullah invites us to instead consider how secularized institutions of Christianity have shaped the West’s legal, political, and cultural frameworks.

This tactic of delimiting and destabilizing encoded binaries ramifies throughout Bismullah’s visual operations. The image of blood punctuating the work’s center was taken by the artist during a 1973 visit to his hometown of Karachi, and documents a goat sacrifice made during the festival of ‘Īd al-Aḍḥā.8 Yet repurposed for Bismullah without indication of its originating circumstances, the image’s indexical referent is partially stripped away and its significance determined by the work and its historical context. The bloodshed could evoke contemporaneous conflicts such as the 1979–89 Soviet-Afghan War—the latter side fueled by American aid funneled through Pakistan—and the violence inflicted by such Cold War proxy battles. The shape might resemble a geographic territory: a map of Britain, to the artist; and to other viewers, a map of Pakistan.9 From another perspective the splatter could appear as drips and drabs of paint, evoking the “American-type” modernism that enjoyed institutional hegemony in Britain and internationally in the postwar period.10 Double-coded as paint and blood, the splash evokes the well-documented history of American art’s ideological uses as a tool in the cultural front of the Cold War.11

While the blood splash is positioned at Bismullah’s center, the green and gold-patterned panels sit on the work’s peripheries. The panels are confined to the margins and physically divided from the work’s interior body, visualizing modernism’s anxious efforts to defend its purity from the frivolity of decoration—famously deemed “degenerate” in Alfred Loos’s “Ornament and Crime”—and its autonomy from the encroachments of utilitarianism.12 These fears converged in the orientalist construction of the category of the arabesque in nineteenth- and twentieth-century scholarship on Islamic art—a history that Bismullah alludes to with the green panels’ golden patterns.13

- 1For readings of other “Cruciform” works, see Zöe Sutherland, “Dialectics of Modernity and Counter-Modernity: Rasheed Araeen’s Cruciform Works,” in Rasheed Araeen: A Retrospective, ed. Nick Aikens (Zürich: JRP Ringier, 2017), 191–98.

- 2I must thank Elizabeth Robles for drawing my attention to this aspect of Bismullah.

- 3Uprisings against racialized violence broke out across the UK in 1980–1, and again in 1985. Following the Brixton Uprising of April 1981, an official inquiry was conducted and published as the Scarman Report. The report did not admit institutionalized racism but attributed rioting to socio-economic and cultural deprivation, which municipal bodies sought to address through programs including funding for “ethnic minority” artists. Stuart Hall, “From Scarman to Stephen Lawrence,” History Workshop Journal 48 (1999): 189–90; Paul Gilroy, There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation (London: Hutchinson, 1987), 136–48.

- 4The commercialism and conservativism of the mainstream British art world was represented, as Victor Burgin has quipped, by the “firm of Saatchi, Saatchi, and Thatcher.” Burgin, The End of Art Theory: Criticism and Postmodernity (London: Macmillan Education, 1986), 46.

- 5The category of a Black Arts Movement in Britain is an insufficient yet frequently used shorthand for a range of artistic practices by diaspora artists roughly spanning the late 1970s to early 1990s. The significance of montage practices for these artists has been noted by scholars including Gilane Tawadros, Elizabeth Robles, and Kobena Mercer, and was an organizing theme of The Place is Here, a recent series of exhibitions on black artists in 1980s Britain curated by Nick Aikens and Robles. Tawadros, “Beyond the Boundary: The Work of Three Black Women Artists in Britain,” Third Text 3, no. 8–9 (September 1989): 121–50; Robles, “Collage and Recollection in the 1970s and 1980s: Three Black British Artists,” Wasafiri 34, no. 4 (2019): 52–63; Mercer, “The Longest Journey: Black Diaspora Artists in Britain,” Art History 44, no. 3 (2021): 496–504; Aikens and Robles, The Place Is Here - The Work of Black Artists in 1980s Britain (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2019), 34.)

- 6Mercer, “The Longest Journey,” 485, 502.

- 7Araeen dates Bismullah’s creation prior to the publication of The Satanic Verses (Email to Author, July 27, 2021). He responded directly to the “Rushdie Affair” in a controversial public artwork, The Golden Verses (1990). See Iftikhar Dadi, Modernism and the Art of Muslim South Asia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 194–95.

- 8Rasheed Araeen, Email to Author, June 27, 2020.

- 9Araeen, Interview with author, July 27, 2021. One of the editors of this special issue has noted the resemblance to Pakistan.

- 10Such was the name that Clement Greenberg gave to abstract expressionism when he argued that it had supplanted Paris as modernism’s world capital. Greenberg, “‘American-Type’ Painting,” in Art and Culture: Critical Essays (Boston: Beacon Press, 1961), 208–29.

- 11Among the many studies of the topic, a canonical source is Serge Guilbaut, How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art: Abstract Expressionism, Freedom, and the Cold War (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983).

- 12Hal Foster elaborates these anxieties in Design and Crime (And Other Diatribes) (London: Verso, 2003), 13–26.

- 13On the history of ornamentalism and orientalism in the nineteenth-century British design reform movement, see Ariane Varela Braga, “Owen Jones and the Oriental Perspective,” in The Myth of the Orient: Architecture and Ornament in the Age of Orientalism, ed. Francine Giese and Ariane Varela Braga (Bern: Peter Lang, 2016), 149–65.

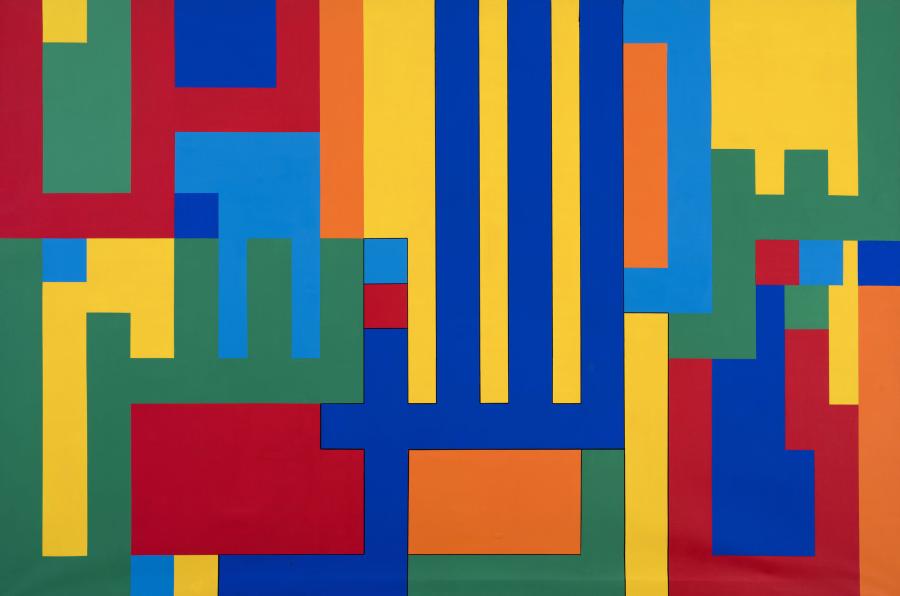

As Bismullah unpacks the discursive constructions and containment of Islamic art, it incorporates another biographical referent situating Araeen’s personhood in this history. In 1970, Araeen was surprised to find that the structural works he innovated in the mid-1960s were misrecognized as “Islamic”.1 The three-dimensional, modular, and symmetrical cubical and lattice forms—such as the free-standing structure Rang Baranga (Fig. 2)—emerged in dialogue with international tendencies of constructivism and kinetic art. They responded to conditions of technological modernity that Araeen was intimately familiar with as a professional civil engineer, in a way comparable to, but distinct from, American minimalism. Despite working at the forefront of the period’s advanced artistic tendencies, critics projected onto Araeen the ethno-racialized identity of an “Islamic” artist and associated the geometric forms of his structures with stereotypes of Islamic art.2 This misrecognition effectively excluded Araeen’s work from the modernist context in which it was produced, and occurred in the same period that institutional racism thwarted his efforts to secure gallery representation.3 This experience was a significant marker in the formation of his political consciousness and self-identification as a “black” and Third World artist in the early 1970s, concomitant with his transition towards a radicalized artistic language in which montage was a core tactic.4

By the time of Bismullah’s creation, the political terrain had shifted considerably from the context of militancy and direct action characterizing the 1970s, to an emphasis on cultural politics and the politics of representation. Multiculturalist and diversity agendas spread through the arts, with the Greater London Council instituting particularly pro-active anti-racist campaigns.5 A strident critic of these agendas, Araeen argued that their separatist funding streams and paternalistic category of “ethnic arts” largely recoded discourses of colonial racism.6 The artistic and political challenge was, as Araeen wrote in 1988, to resist integration within the prevailing terms of the art establishment and sustain the radicalism of what he defined as “black consciousness” in artistic practice: “not an alternative to or a complete rupture from the mainstream,” but a “critical distance or radical position within its broad spectrum.”7

Operating from such a position of radical critique, Bismullah deploys montage to stage and deconstruct those now-familiar orientalist binaries: East/West, Islam/Christianity, tradition/modernism, periphery/center. In addition to the corner panels’ references to Islamic architecture, their verdant hue evokes the shade of garments promised to the elect in paradise in the Qur’an (76:21). Green, the artist has noted, also signifies nature and youth, addressing the state of “under-development” produced by processes of colonialism.8 At the same time, green appears in the flags of modern nation-states including Pakistan, alluding to pan-Islamic aspirations and the complexities of their territorially-bounded manifestations. In this context, green might call to mind the modernist ideals—and poetic aesthetics—of Pakistan’s founding figure, the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal (1877–1938). Although he supported an independent Pakistan, Iqbal conceived an Islamic state as a means to transcend national and ethnic boundaries, and Islam as a framework to realize the potential of human universality. Iqbal reworked the ideas of European philosophers such as Henri Bergson and Friedrich Nietzsche and recontextualized them—in a way perhaps comparable to Bismullah’s operations—within a reconceived structure of Islam that responded to the experiences and imperatives of colonial modernity.9

While the green panels are divided and pushed to the work’s margins by the cruciform shape organizing the candle photographs, the images' aleatory symbolism traverses these fissures by transforming particularity into polyvalence. Photographed on an unknown date before Bismullah’s conception, they evoke the thematics of light as a vital conduit within and between a plurality of traditions. The Qur’an’s prominent “Light Verse” (Qur’an 24:35) echoes metaphors of God as light that abound across the New Testament and Hebrew Bible.10 To the artist, the candles prompt memories of celebrating Diwali, the festival of lights shared across Hinduism, Jainism, and Sikhism.11 Born into a Muslim family in pre-partition India, Araeen recalls Muslims partaking equally in the festivities, indexing the Indian subcontinent’s history of pluralistic co-existence prior to, and continuing despite, the fissures of colonialism and communalism. Light further links Islamic thought to the legacies of Neo-Platonism through the Ishrāqī or Illuminationist tradition, wherein the possible unity of revelation and reason formed a key problematic.12 Light is also the metaphoric root of European enlightenment, whose philosophies are foundational to colonial modernity and have been redeployed—as by Iqbal—in struggles against it.

- 1Araeen, “How I Discovered My Oriental Soul in the Wilderness of the West,” Third Text 6, no. 18 (1992): 91–3.

- 2Araeen, 91–93.

- 3Araeen, “How I Discovered,” 96–8.

- 4As articulated in Araeen's “Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto” (Black Phoenix 1 (1978): 3–12), the artist's political consciousness was formed in the discourses of political blackness that emerged in Britain in response to the historical experiences of British colonialism. Distinct from discourses on blackness defined in relation to African diasporas, political blackness was defined primarily in relation to histories and experiences of racist oppression and encompassed multiple ethno-racial identities.As Aikens and Robles detail the variation in practices of capitalizing b/Black is rooted in the multiplicity of these histories and political traditions; Araeen himself commonly writes "black" in lowercase. Aikens and Robles, The Place Is Here, 10–1.

- 5Richard Hylton, The Nature of the Beast: Cultural Diversity and the Visual Arts Sector: A Study of Policies, Initiatives and Attitudes 1976-2006 (Bath: Institute of Contemporary Interdisciplinary Arts, 2007), 43–56.

- 6Araeen, “From Primitivism to Ethnic Arts,” Third Text 1, no. 1 (1987): 6–25.

- 7Araeen, ed., The Essential Black Art (London: Chisenhale Gallery in conjunction with Black Umbrella, 1988), 5.

- 8Rasheed Araeen and Jean Fisher, The Triumph of Icarus: Life and Art of Rasheed Araeen (Karachi: Millennium Media, 2014), 132.

- 9On Iqbal’s “intellectual cosmopolitanism” see Javed Majeed’s introduction to Muhammad Iqbal, The Reconstruction of Religious Thought in Islam (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2012), xii–xvi.

- 10See Gerhard Böwering, “The Light Verse: Qur’ānic Text and Sūfī Interpretation,” Oriens 36 (2001): 116, 120, 120n33.

- 11Araeen, Email to Author, October 13, 2020.

- 12Majid Fakhry, A History of Islamic Philosophy, 3rd ed (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004), 286.

Through these operations, Bismullah anticipates Araeen’s contemporary project of translating modernism into a reconceptualized visual and intellectual framework of Islam. This endeavor is apparent in Guftugu I (A discussion between Al-Bīrūnī and Ibn Sīnā about Aristotle) (2014, Fig. 3), of the “Homecoming” series (2010–14). The work reimagines the Islamic tradition of calligraphy within chromatic blocks whose linear configurations also evoke the concrete art abstractions of Richard Paul Lohse (1902–88).1 Its title references a correspondence that, to Seyyed Hossein Nasr, is “one of the highlights of Islamic intellectual history . . . and science in general.”2 This encounter is notable for the challenge that Abū Rayḥān Muḥammad ibn Aḥmad al-Bīrūnī (973–1048 CE) poses to the Aristotelian cosmology of Abū ‘Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn ‘Abd Allāh ibn Sīnā (980–1037 CE) by advocating a scientific method of empirical observation and experimentation. The reference recalls al-Bīrūnī’s significance for Iqbal, who believed that the scholar’s radical break with Hellenistic philosophy’s “static view of the universe” enabled Islamic thinkers to innovate the scientific method that has since been claimed as a “European discovery.”3 Within these works, and against the violent processes that have universalized European colonial modernity, Araeen insists on the universality of modernism understood as an ongoing process of translation and insurgent critique.

- 1For an analysis of the artistic and philosophical significance of the "Homecoming" series, see Iftikhar Dadi, “Rasheed Araeen’s Homecoming,” in Amra Ali and VM Art Gallery, eds., Rasheed Araeen: Homecoming (Karachi: VM Art Gallery, 2014), 87–98. Since this article was written, Araeen has presented a new exhibition extending the inquiries initiated with the "Homecoming" works, titled “Islam and Modernism: Past to Present” (COMO Museum of Art, Lahore, April 6–July 1, 2022).

- 2Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Mehdi Mohaghegh, Al-As’ilah wa’l-Ajwibah (Questions and Answers), (Kuala Lumpur: International Institute of Islamic Thought and Civilization, 1995), quoted in Rafik Berjak and Muzaffar Iqbal, “Ibn Sīnā–al-Bīrūnī Correspondence,” Islam & Science 1, no. 1 (2003): 92

- 3Iqbal, Reconstruction, 103, 106.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.2

1. Kylie Gilchrist, "Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah" Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 2 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.2.

Gilchrist, Kylie. "Rasheed Araeen’s Bismullah." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 2 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.2.