Emily C. Floyd is Lecturer of Visual Culture and Art before 1700 at University College London and Editor and Curator at the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Culture of Religion at Yale University (MAVCOR). Her current research centers on normative whiteness, implicit depictions of race, and intersecting ideas of sanctity, monstrosity, and the body in colonial South America. Her book on prints made in colonial Lima and their regional and transatlantic impact, The Mobile Image: Prints from Lima in the Andes and Beyond, 1584-1824 is forthcoming in 2025 from University of Texas Press.

MAVCOR Editor and Curator Emily C. Floyd interviewed Friar Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho, Director of the Museum of the Monastery of Saint Dominic, Lima (Convento de Santo Domingo de Lima) and a Dominican friar. They met on March 17, 2017 in the museum to discuss the facial reconstructions of the Peruvian Dominican saints Rose of Lima, Martin of Porres, and John Macías, a process that began in August 2014.

Saint Rose of Lima, born Isabel Flores de Oliva in 1586 in Lima, then capital of the Spanish Viceroyalty of Peru, an administrative region spanning much of Spanish-speaking South America. Saint Rose was a third order Dominican known for her chastity and acts of penance. After her death in 1617, her supporters almost immediately began promoting her sanctity. As a result, Saint Rose of Lima was the first New World saint to be canonized, in 1671.

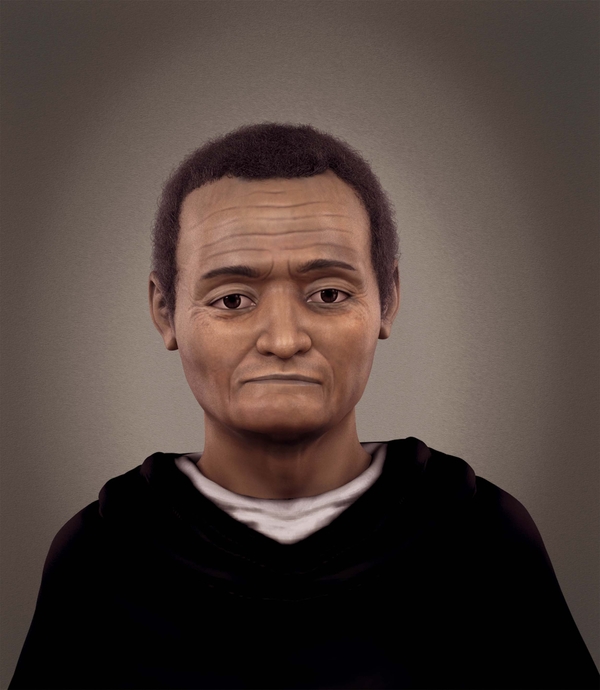

Saint Martin of Porres was born 1579 in Lima, the illegitimate son of a Spanish gentleman and freedwoman of African or possibly indigenous descent. As people of African or indigenous heritage were not allowed to become full members of the religious orders, Martin joined the Dominicans as a donado, or religious servant. He was particularly known for his skill at healing, serving both in the Dominican infirmary and out in the community at large. He died in 1639 at the age of sixty. Despite continuing devotion to Saint Martin after his death, he was not beatified until 1837, and was only canonized in 1962.

Saint John Macías (1585-1645) was born in Extremadura in Spain and immigrated to Peru where he entered the Dominican Order as a lay brother. Like Saints Rose and Martin he was known for his humility. Saint John and Saint Martin were close friends in life. Saint John was beatified in 1813 and canonized in 1975.

Emily C. Floyd: Could you tell me a little about the history of the project? How did it come to be? Whose idea was it? Why did you all find the idea appealing?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: The project of the facial reconstruction of the Peruvian saints wasn’t our idea. At the time I was the Prior of the monastery; I’m now Director of the museum. Some young Brazilians got in touch with me who turned out to be scientists, one of them is a forensic specialist, a forensic anthropologist, and the other is a specialist in 3D and the like. They suggested to me the idea that we might make a facial reconstruction of Saint Martin because they were familiar with Saint Martin as he is rather better known . . . no, excuse me, more Saint Rose, Saint Rose is better known in Brazil than Saint Martin of Porres.

This was in our initial communication and then they came here to the monastery to speak with me. At the same time I knew this was possible because we Dominicans have the same kind of thing for the face of Saint Dominic. There was an antecedent there; this wasn’t a new thing. There is a marble statue that we call the true effigy, or the true visage, or true face of Saint Dominic, which was made after the second World War using the technique of placing small pins in the skull of the saint itself and filling it with clay until you end up configuring the head that the skull, according to the techniques of that era, provides. Once it was completed in clay it was carved in marble and then the skull was cleaned and returned to the reliquary.1

- 1Jeffrey David Feldman offers a slightly different description of the creation of the Saint Dominic true portrait. See Jeffrey David Feldman, "The X-Ray and the Relic: Anthropology and Early Modern Bodies in Modern Italy," in In corpore: Bodies in Post-Unification Italy, eds. Loredana Polezzi and Charlotte Ross (Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 2007).

They told us these stories in the novitiate and during our studies, that we have the famous true effigy of our father Saint Dominic, which is in Bologna just to the side of the tomb of Saint Dominic. I have the pleasure of having visited; I took many pictures when I went, obviously. So we already knew about this. We already knew that this technique existed. When the Brazilians came they explained to me that it wasn’t necessary to do this but rather they simply had to take a cranial scan with a facial CT-scanner so that the cranium would be digitized in 3D. Then using this they could reconstruct the face as such, indeed there is software that does this. So it wasn’t invasive as in the case of our father Saint Dominic in which they had to work directly with the actual skull.

I consulted with the community chapter, we asked for permission from the Dominican province and they said yes, because we after all in some ways already have an antecedent [for doing this] and furthermore we had quite a curiosity to know how they looked as we’ve always had images of Saint Martin, of Rose, and of John that were very stylized. Saint Martin sometimes looks either too African or very little African but with dark hair. There is a truly wide range. Regarding Saint John Macías we had no idea. And of Saint Rose what are most familiar are her representations in Cuzco School paintings, whereas for Martin and John there basically aren’t very many Cuzco School paintings.1 I can think of a couple of works and nothing more.

- 1The Cuzco School refers to a style of painting produced in Cuzco, Peru during the colonial period, in particular the eighteenth century.

So we accepted the proposal, which is within our right to do so because the relics are the property of our order here in Peru. We made the agreement. The University of San Martín de Porres, Lima participated with the facial CT-scanner from their hospital or university clinic. We delivered the skulls with all the security in the world. The police came, the army, and everyone else, because after all these are also human skulls, they are human remains, not just relics, and there was a lot of television and that kind of thing.

They made the 3D scans and took them on a USB off to Brazil where they have more advanced computers in order to be able to do this. As time passed they went giving them to us little by little. The first was Saint Rose of Lima. They began with Saint Rose of Lima because the bishop of a Brazilian city [Guarujá, in the state of São Paulo], his diocese or parish is called Santa Rosa de Lima and so he wanted this and he paid for the work. They [the Brazilians who produced the reconstructions] are an NGO called EBRAFOL [Equipe Brasileira de Antropologia Forense e Odontologia Legal – Brazilian Team for Forensic Anthropology and Legal Odontology] with Paulo Miamoto and César Morraes as the two who carried out this work. EBRAFOL is their NGO. The bishop helped to pay for all of this. And so they began with Saint Rose of Lima, and I said, no, not only Saint Rose, but also Saint Martin and Saint John Macías. I put them in contact as well with my sisters in the convent of Saint Catherine (Santa Catalina) of Arequipa so that the Blessed Ana de los Ángeles could also be done. They were interested in doing it and so they also have the true face of the Blessed Ana.

We also learned through various sources that they [EBRAFOL] showed us that they had already done this same process with other saints in Europe, such as Saint Anthony of Padua and Saint Mary Magdalene, and a few others that I’m not remembering at the moment. Which is to say, we aren’t the first, they had already had the experience in Europe of making this kind of facial reconstructions.

The whole process was completed and we had a special ceremony with the participation of the bishops and everything in order to do the unveiling of the true faces of Saint Martin, Saint Rose, and Saint John. It was both a surprise and a wake up call for us in some ways, when we saw Saint Martin for example, who was a very normal mulatto of African heritage, very average, very ordinary. He wasn’t at all stylized, nor excessively beautiful, nor divinized in any way, nor sacralized. This captures your attention, because [it means] we are all called to sainthood. We don’t necessarily have to be spectacularly beautiful. We are all called to sainthood.

Rose was surprising. Really Saint Rose of Lima is very lovely. Obviously the facial reconstructions capture the face at the age in which the people died. Martin is a person around sixty years old. Saint Rose of Lima was thirty, thirty-one when she died. So she has that face. And Saint John Macías died at around sixty as well. It was beautiful to see them, to recognize them and now, well, they are our friends here with their true faces. Now they aren’t in our imagination.

One of the things we have to recognize is that this is a face generated obviously in 3D with all of the corresponding techniques and scientific procedures and the studies that they did of the skulls, but this is how it is. Which is to say, we didn’t influence them to improve or touch-up or make them so they look more saintly, we didn’t do absolutely anything, they are how they are. Some people have said to me, well, Saint Martin and Saint John need to be rejuvenated. And they have the software to be able to do this but we have left it as it is. Maybe at some point but it isn’t a concern of ours to do this.

So now we have Saint Martin, Rose, and John with us as they are. We asked them [EBRAFOL] that this not be an exclusive thing and that no one should have to pay author rights in order to use them. One of the conditions was that they be public and completely free and open. They published the reconstructions on Wikipedia in high resolution so that anyone can download them, make their prints, their posters, their prayer cards and now that we know Saint Rose and Martin and John, well, they can have them too and you don’t have to pay or go to a special place in order to do so. I think that they are with us and the church is universal and this is basically how it has to be.

Emily Floyd: With that you’ve really responded already to almost all of the questions I was going to ask! One thing that occurs to me is about the NGO and if you could tell me a little bit more about them. Is reconstructing the faces of saints their general mission?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: No, no. The reconstruction of the saints is the cultural side of things. We didn’t pay anything; they got financial support for all of it. Part was from the University of San Martín and the other was from the University Inca Garcilaso de la Vega here in Lima. The rest they acquired. We didn’t give absolutely anything. . . .

They’ve done other saints but the NGO’s mission isn’t to do this. They reconstruct faces, for example, of skulls of people found in mass graves in order to identify who they are. I believe they’ve also done a number of these kinds of projects. And then they’ve also reconstructed and made prostheses for mutilated animals, like a bill for a pelican or a toucan or a parrot, or a shell for a tortoise. They’re able to do that kind of thing with the same technology. And obviously they do everything involved in the reconstruction of human skulls. Now, I understand, I’m not sure but I think this is correct, that they have an agreement with the University Inca Garcilaso de la Vega in order to reconstruct the Lord of Sipán or the Lady of Cao, so that we can know them, to see their physiognomic features, and of course to carry out an anthropological-scientific study of the cranium.1 When they did Saint Martin of Porres, for example, he didn’t have teeth. It seems he lost them very early, or at a more or less young age. He had two teeth and for this reason his jaw is inclined, twisted, this and other things are the kind of thing a specialist can read in the skull. So they are dedicated to this and carry out their work both in Brazil and in the places where they are called.

Emily C. Floyd: And are they a Catholic organization?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: No, no.

Emily C. Floyd: For you all what relationship do the reconstructions have to the well-known colonial images? You’ve already spoken about this a little bit but, for example, for Saint Rose we have the painting by Angelino Medoro that shows her after her death, and it seems to me that we have a painting of Saint Martin that shows him while he was alive, right?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: Yes, and of Saint John Macías as well.

Emily C. Floyd: Of all three then. Could you comment on that?

- 1EBRAFOL completed their reconstruction of the Lord of Sipán in September 2016. The Lord of Sipán was a Moche ruler whose mummy was discovered at Huaca Rajada, Sipán, Peru in 1987 by archeologist Walter Alva Alva. The Moche ruled the northwest coast of Peru from around 100-800 CE.

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: Well, one of the things that the Brazilians said was that this was the first time that it had happened for them that the facial reconstructions looked a lot like the paintings or old sculptures of the saints. For example, there is a small painting of Saint Martin of Porres in the nuns’ convent of Santa Rosa . . . and the reconstruction is 90% similar. And here in the convent we have a sculpture of Martin that is 95% similar. We didn’t know that we had him with us in this way.

Of Rose by Angelino Medoro, more than the painting with the mortuary visage was the painting that he made as he remembered her.1 Rose of Lima was someone who after all provided certain services in his home as she was a friend of his wife and he knew her. So after her death he portrayed her as he remembered her, and the face of the facial reconstruction is very very close to that painting. Keeping in mind that the painting is seventeenth century and all. They said that this was the first time that this had happened for them and that really in the other facial reconstructions they have done of saints the face they have revealed has never looked like old paintings or sculpture. This is the first time and for them that was a great surprise as well.

- 1Angelino Medoro was an Italian artist who moved to Peru in 1600, a painting of Saint Rose on her deathbed is attributed to the artist.

Emily C. Floyd: I’m also interested in the public's reaction, both secular and religious, both of devotees and of average people off the street, both here in Peru and in other places.

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: Well basically people have accepted it. They’ve accepted it. Some say, no, he’s very old; you need to make him prettier, because people have obviously become accustomed to the idealization of the face that they supposedly want of the saint of their devotion. For us precisely for this reason making them very concrete and normal people is in all ways a call to sainthood.

Yes, it has been accepted even on an international level. We’ve seen that many entities dedicated [to the saints], principally to Saint Martin and Rose, who are the best known, have removed the head from their image and have replaced it with the head from the facial reconstruction using Photoshop, I imagine, or something similar. We realized this because afterward we went checking around and seeing how the process had gone. What this implies is that now that we’ve discovered how he is, this is how we want him. We’ve also had requests from some brotherhoods [lay religious organizations dedicated to individual saints] asking, “Where can we get an image with the true face?” But there aren’t any yet because we hadn’t thought of doing that yet ourselves.

Emily C. Floyd: They wanted to make a sculpture?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: A sculpture. To change the Martin that they have and take out in procession for the true one. Others say, no, we want to stay with ours because we know it and this image has been venerated for 100 years and the people simply like it the way it is, and even if it isn’t very pretty they aren’t going to change it. In general there hasn’t been any real problem, no conflict or discussion or anything, they’ve been accepted. Some like them, some don’t, as I’ve said, they insist on a prettier image, and Martin is a real man, just like Rose and John.

Emily C. Floyd: What does it mean for you all to have the facial reconstructions of the saints?

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: Its not that it has to mean anything particularly important, in the sense that the devotion to the saint and what the saint inspires in your heart is much more important than a physical thing that you can see. So Martin is in the heart of many people. Most of all Martin, then Rose, and then John, at least here in Lima and in Peru. This, then, hasn’t changed. This continues the same. And I think that seeing Martin so normal and so everyday has even energized some people. Perhaps it surprised some people. There hasn’t been any problem, rather the opposite, I believe that there has been increased closeness with the people because we are very soft-hearted, “Poor little thing, we have to help,” that kind of thing, no? And seeing little Martin just as he is has inspired perhaps even more tenderness, more affection, more emotions toward him. And the same with Rose, saying, wow, how beautiful, she was so lovely, look how one can be lovely and be a Saint, you don’t have to be ugly to be a saint. So it has contributed a little as well in that sense. I believe that it has been very good.

The meaning though as a very very transcendent contribution isn’t so substantial, because Martin, Rose, and John are in the hearts of the people and they know them as they are. Perhaps it helps a little, although I’m not sure that the word “help” is the right one, but it is really a secondary thing, it isn’t the main thing. Because the devotion has to have Rose, Martin, and Saint John there anyway. It gives a little push but it really isn’t a big deal.

[Floyd and Ramírez concluded the interview but then continuing chatting and decided to return to recording]

Emily C. Floyd: Let’s see, we were talking briefly about the commerce in images in Europe in comparison to here in Peru.

Fray Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho: Yes, one of the things that I’ll tell you as an anecdote is that we here in Peru, as you can see, haven’t developed extensively the commerce in images or religious things. There isn’t any. And for us, at least for us the Dominicans, we feel very ashamed or sorry sending out to make things, be they images or prayer cards, or whatever, in order to sell religious things. As we feel ashamed, we don’t want people to confuse us with commercial things or the like. But now that I’ve been in European and I’ve been between Italy and Spain and a few other places, the huge malls that exist there for religious things surprised me.

Inside Saint Peter’s, near Saint Peter’s, there by Padre Pio, they’ll sell you I don’t know what with the face of Padre Pio on it, and it’s the very Capuchin friars who do this . . . it isn’t the common people. Fatima, my god, so much commerce! I know that this feeds many people because someone is selling it, someone is making it, but we still felt this shock.

We don’t dare to make things precisely for this reason because we don’t want people to misinterpret us. But it turns out in other contexts it’s normal, it’s very natural; it’s normal to see a little bottle with holy water and the face of Saint Martin. So we didn’t do this. I don’t claim that it will ever reach that level, but we are making an effort to have something that the devout faithful can take with them that they like and that they’ll feel affection for, as a nice souvenir of their presence here in Lima. But this still was a shock that I had never felt before, I had never seen before. I really felt like an imperialist, I don’t know, for selling a prayer card, but it turns out that wasn’t really the case. This is just an anecdote to share.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.int.2017.1

1. Emily C. Floyd, "Reconstructing the Faces of the Saints, an Interview with Friar Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho, O. P.," Conversation, in MAVCOR Journal 1, no. 1 (2017), doi:10.22332/mav.int.2017.1

Floyd, Emily C. "Reconstructing the Faces of the Saints, an Interview with Friar Luis Enrique Ramírez Camacho, O. P." Conversation. In MAVCOR Journal 1, no. 1 (2017). doi:10.22332/mav.int.2017.1