Max is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at the University of Pennsylvania specializing in Islam. His dissertation focuses on Islamic materiality, especially contemporary Islamic tattooing and Halal consumption, using a combination of ethnographic methods and digital humanities techniques. This project examines how class, gender, and ethnicity engender feelings of Islamic authenticity through urban and virtual networks.

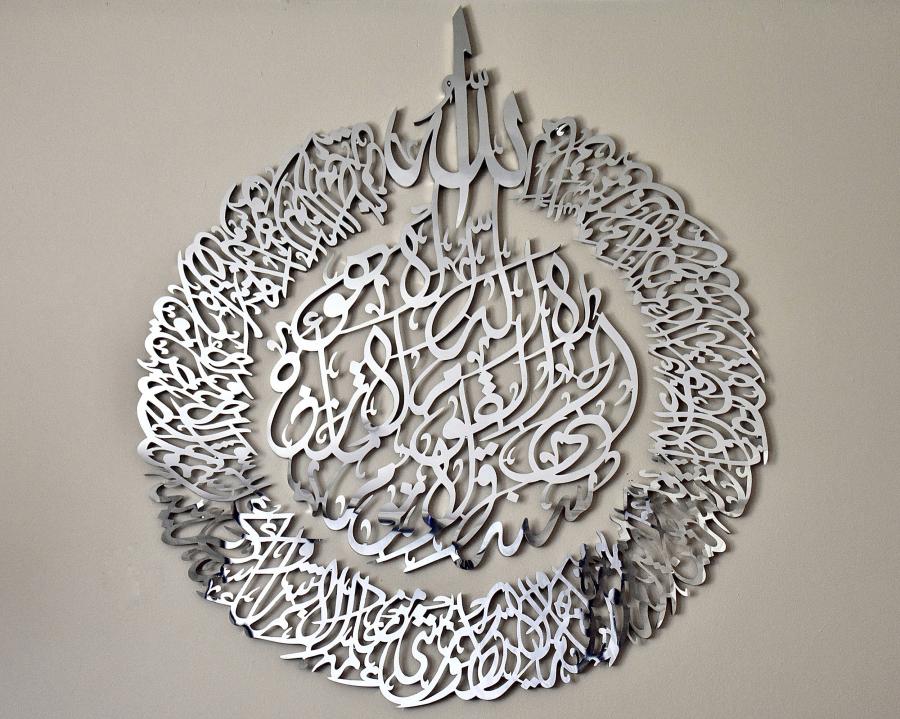

Crowned by the word “Allah,” a dense piece of Arabic calligraphy carved out of stainless steel wraps around an embellished center. The text is the ayat al-kursī, or “The Throne Verse,” a portion of the Qur’an (2:256) often recited before sleep or travel because of its reputation for spiritual and physical protection.1 While the Illinois-based company Modern Wall Art produces the above “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” at least six other businesses manufacture their own ayat al-kursī pieces in the same circular visual style.2 For example, Wall Art Istanbul features a virtually identical work on their webpage banner entitled "Ayatul Kursi Metal Wall Art." The companies, Lamasset and Irada Arts, market similar pieces featuring the ayat al-kursī, albeit printed on canvas in the former case and applied as vinyl in the latter.3 I have found three additional businesses that sell almost indistinguishable ayat al-kursī pieces.4 These pieces of Islamic decor appeal to different tastes in spite of the repetitiveness of their visual content. By attending to the specific production method and branding of “Ayat Al Kursi Round,” we can identify how the materialization of God’s words in wall art entangles Islamic ethics and the aesthetics of class formation.5 Through aspirational middle-class consumption of this object, buyers align their consumer values, taste, and desired socioeconomic status.6 More specifically, “Ayat Al Kursi Round” configures “conscious capitalism” in Islamic terms that widen its market appeal and resonate with neo-Salafi logics—in this case, that Muslim unity requires the minimization of differences related to sect and authority.

Retailers specializing in Islamic wall art have proliferated globally since 2010, aided in large part by the spread of social media and e-commerce platforms. In this emergent field of Islamic consumption, Islamic decor is not only a feature of the market, as it was in previous brick-and-mortar shops, but the focal point. In my survey of these Islamic wall art businesses, I have identified nine that specialize primarily in Islamic wall art and sell their products through their own website, with the majority based in the United States and Canada.7 This does not include the dozens more marketing their work through third-party e-commerce sites such as Etsy or Wayfair, or social media sites like Instagram or Facebook, or as a tertiary product amidst other Islamic leisure goods, such as modest clothing and hygiene products.8 Social media and e-commerce sites have been vital to the development of this market. In addition to providing inexpensive marketing and customer engagement technology, they have also fostered a culture of display in which home decor not only beautifies a space but communicates taste and socio-economic status to relatives and friends. In this culture of display, businesses associate their brand with the affluent domestic leisure of middle-class life by, for example, sharing photographs of their products in well-furnished homes.

In general, producers differentiate their Islamic wall art through medium, production process, and branding. Saleha Arts, for example, specializes in original paintings by Saleha Patel that mix calligraphy and abstract representations.9 Conversely, Irada Arts focuses on calligraphic vinyl decals of excerpts from the Qur’an that are relatively inexpensive and easily installed and removed, ideal for someone renting the property in which they are placing the art. Businesses that sell their work on third-party e-commerce sites (like Etsy) tend to use more affordable materials and automated production processes. One example is IslamicWallArtStore, whose products consist of laser-cut medium-density fiberboard (MDF) coated with chrome powder. IslamicWallArtStore and other Etsy retailers lack the personalized websites and social media profiles with which more established businesses like Saleha Arts, Irada Arts, and Modern Wall Art distinguish themselves. As part of her "Relearn Islam with Me," branding, Patel maintains a blog on her website on which she writes about the different aspects of the Islamic traditions (Hadith) she incorporates into her work. Irada Arts has used its Facebook account to garner feedback about its "Seerah artwork" series from potential customers, projecting an interactive creative process to its followers. And Modern Wall Art, as discussed below, regularly directs charity drives and shares about the Muslim experience of founder and co-owner, Syed Rahman. Medium, production method, and branding work in tandem to stratify the field of Islamic wall art producers.

Out of all the Islamic wall arts businesses in North America, Modern Wall Art, which produces the “Ayat Al Kursi Round” photographed above, has become arguably the most visible, at least on social media.10 It began displaying products in 2008 and 2009 through Rahman’s personal Facebook page before starting to sell its products on third-party e-commerce sites in 2014. While now it almost exclusively fabricates Islamic art, the name “Modern Wall Art” reflects the original intention of Rahman to focus more broadly on abstract metal art. He initially planned to devote one-eighth of his inventory to Islamic pieces but, upon receiving a deluge of Facebook requests for his first piece, a stainless steel basmala, he shifted to Islamic wall art.11 In a 2019 interview, Rahman explained that the interactions with customers and the blessings (baraka)12 he acquired through producing Islamic wall art increased his piety and ritual observance.13 In this telling, Rahman connects the longstanding belief that materialization of the Qur’an by hand imparted blessings to the scribe with his contemporary production of Islamic wall art. A significant portion of the Instagram page for Modern Wall Art documents his transformation, with Rahman sharing before-and-after photographs of himself without and with a beard—interpreted as a marker of increased piety—as well as stories concerning his experiences as a Muslim.

As his religious observance grew over time, so did Modern Wall Art’s business. Its flagship showroom was opened in Skokie, Illinois in 2016. As of January 2019, it had thirty employees dealing with custom design, hand-fabrication, and shipping. In 2020, it opened a second location in Bridgeview, Illinois, roughly an hour away from its flagship store. Although it is open to accepting custom projects, Modern Wall Art maintains certain criteria for what it will produce: custom works must feature verses from the Qur’an, be the name of a couple or a child, or be a business logo. Rahman explained that even though he is Sunni, he does not want the work of Modern Wall Art to be “in favor of any sect” because “we cannot be divided."14 He further elaborated that “the beauty of being neutral is you are friends with everyone.”15 This policy has led Rahman to decline projects for Arab Christians and Sikhs, as well as for Isma‘ili Shi‘is. From the perspective of Rahman, the restriction of Islamic wall art to the lowest common denominator of Islamic culture, the Qur’an, unifies the Muslim community. Practically speaking, this policy also benefits Modern Wall Art by expanding their market appeal and limiting damage to their brand. At the same time, the rejection of salient intra-Muslim differences exemplifies a neo-Salafi logic in which variegated sects and schools (madhāhib) divide an otherwise unified Umma. In this framing, Modern Wall Art has marginalized affinity to the Isma‘ili Shi‘i Imams and other extraordinary figures as peripheral to the Qur’an by not producing Isma‘ili Shi‘i-specific objects. In spite of their custom objects policy, Modern Wall Art has occasionally found their posts a site for intra-Muslim debate, such as one containing an image of Zulfikar—the sword of Ali ibn Abi Talib that often serves as a metonym for him—with the shahāda, or declaration of faith, inside of it.16

In the case of Modern Wall Art, its use of stainless steel and on-site handcrafting, along with its sponsorship of charity drives, appeals to middle-class or aspirational middle-class consumers. The use of stainless steel, as the owner of Modern Wall Art notes, makes the products age-proof. Where laser-cut MDF models or vinyl decals appeal to those temporarily decorating an apartment, the durability of stainless steel is ideal for more affluent homeowners. The durability of stainless steel also takes on additional significance because the objects crafted by Modern Wall Art often include language from the Qur’an. When asked about the disposal of pieces damaged beyond repair, Rahman suggested that one would have to burn them, but that using age-proof materials would solve this potential dilemma.17 For those willing to spend more in order to be socially conscientious, the “About” page of Modern Wall Art’s website assures potential buyers that it creates jobs by handcrafting its products. Modern Wall Art also frames this decision in Islamic terms, explaining that human labor infuses the very material of Islamic wall art with blessings (“baraka”). Charity is also central to the branding of Modern Wall Art. In 2019, Modern Wall Art raised over $150,000 through both large-scale and small-scale campaigns; for example, Modern Wall Art contributed funds for food aid to Afghanistan and for rent money for a disabled Muslim immigrant in Chicago. These practices are consistent with “conscious capitalism,” including expansive notions of value and stakeholder well-being.18 Like conscious capitalism, Modern Wall Art attaches notions of social good to class stratification, thereby translating middle-class consumer ethics for Muslim consumers. In this way, “Ayat Al Kursi Round” imbricates religious and class formation in its very materiality and radiates that process on social media and home walls.

- 1Sayyed Hossein Nasr et al, The Study Quran: A New Translation and Commentary (New York: HarperCollins, 2015), 110.

- 2To distinguish between materializations of the verse of the Qur’an and the verse itself, I use quotation marks around the titles for objects provided by businesses (e.g. “Ayat Al Kursi Round”) and ayat al-kursī for the verse.

- 3Lamasset manufactures their products in Tunisia but has a mailing address in Nice, France. Irada Arts is based in both Amman, Jordan and Valley Stream, New York. They located their Amman facility in Hayy al-Kharabsheh, a neighborhood that developed around the Sufi leader Nuh Ha Mim Keller.

- 4Specifically, the Washington, D.C.-area-based Sukar, California-based, IslamicWallArtStore , and the UK-based TheRoyalDecors.

- 5I use “branding” here and below to mean the public perception of a business informed by logo, corporate ethics, and marketing. In doing so, I elide the business studies distinction between “brand” as logo and visual aesthetics, and “corporate image” as general reputation.

- 6In describing some of these consumers as “aspirational middle class,” we can acknowledge, as Justine Howe does, the self-fashioning role of consumption. And even without knowing the socio-economic status of consumers, we can determine the resonance between their consumer values and purported middle-class values. Justine Howe, “Daʿwa in the Neighborhood: Female Authored Muslim Students Association Publications, 1963–1980,” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 29, no. 3 (January 2020): 292-296.

- 7Specifically, Salam Arts, Saleha Arts, Irada Arts, Islamic Art Store, Wall Art Istanbul, Lamasset, Sukar and Modern Wall Arts. All of these businesses ship internationally.

- 8Malika Ayubbi is one such Instagram artist. She is also one of the few prominent black American Muslim women producing Islamic wall art, indicating the persistent limited social capital afforded to Black Muslim influencers by global Muslim consumers.

- 9For example, Patel’s "Queens of Jannah" (2018).

- 10Having just crossed the 100,000 follower mark at the end of April 2020, Modern Wall Art has four times as many Instagram followers as the next most prominent Islamic decor business. As of May 2020, Irada Arts, which has a broader variety of offerings, has significantly more followers than it on Facebook, with 87,000 followers compared to Modern Wall Art’s 24,000.

- 11The symbolic value of this being the first piece would not be lost on Muslim consumers. The basmala (“In the Name of God, the Merciful and Compassionate”) is regularly recited at the beginning of ritual practices, as well as on quotidian personal and professional occasions.

- 12Baraka is a beneficial divine force that transmits through extraordinary individuals and objects.

- 13Syed Rahman, interview by author, Skokie, IL, August 6, 2019.

- 14Rahman, interview, August 6, 2019.

- 15Ibid.

- 16The controversy began when Instagram user @emilek10 responded that Modern Wall Art should have entitled Ali “Imam Ali” to reflect Shi‘i sentiments which more closely ally with the iconography associated with Ali, rather than “Hazrat Ali” which is the way Sunnis refer to him. This led to a discussion—sometimes heated, but generally empathetic—about the divisiveness of such debates.

- 17Rahman, interview, August 6, 2019. Rahman’s suggestion here likely stems from incineration—as well as burial—being a ritually acceptable method for disposing of a severely damaged copy of the Qur’an.

- 18Popularized by Whole Foods founder John Mackey and movement leader Raj Sisodia, conscious capitalism contends that capitalism can generate value and facilitate good lives for all involved stakeholders if it is properly configured. Nicole Aschoff has criticized this approach as naive for ignoring the unsustainable, endless consumption and competition built into capitalism. Nichole Aschoff, The New Prophets of Capital (Booklyn: Verso Books, 2015).

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.1

1. Max Dugan, "Ayat Al Kursi Round," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 2 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.1.

Dugan, Max. "Ayat Al Kursi Round." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 2 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.1.