Frank Graziano is the John D. MacArthur Professor Emeritus of Hispanic Studies, Connecticut College. In addition to Historic Churches of New Mexico Today, Graziano’s books from Oxford University Press include Miraculous Images and Votive Offerings in Mexico (2016) and Cultures of Devotion: Folk Saints of Spanish America (2007). Hundreds of additional photographs from Graziano’s religion projects are available to researchers at the Center for Southwest Research and Special Collections, University of New Mexico, here.

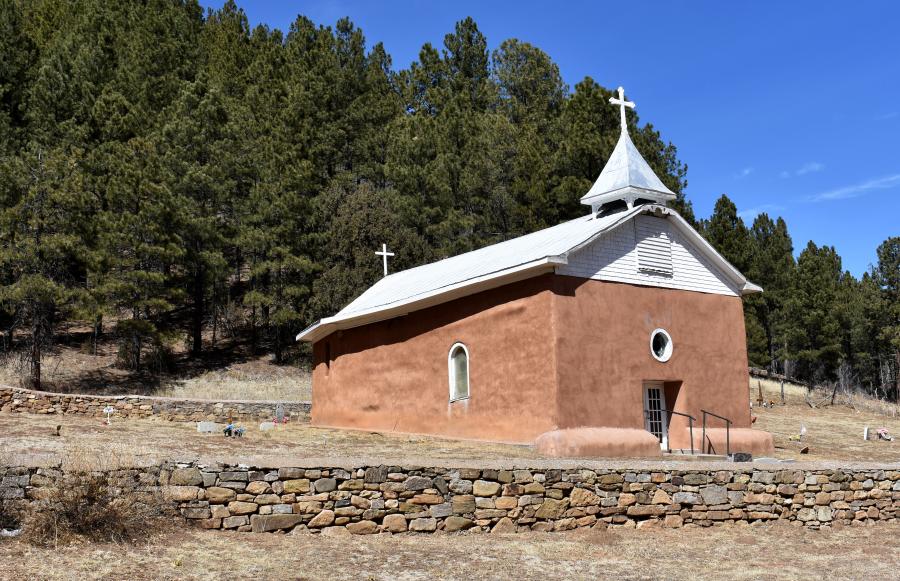

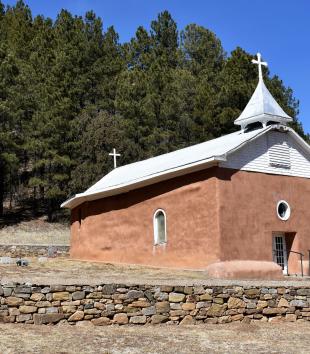

San Antonio Mission Church

San Antonio Mission Church

Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Our Lady of Purification)

Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria (Our Lady of Purification)

Immaculate Conception Mission Church

Immaculate Conception Mission Church

St. Augustine Mission Church

St. Augustine Mission Church

San Rafael Mission Church

San Rafael Mission Church

San Francisco de Asís Mission Church

San Francisco de Asís Mission Church

Santa Rosalía Mission Church

Santa Rosalía Mission Church

San Isidro Chapel

San Isidro Chapel

San Francisco Mission Church

San Francisco Mission Church

St. Patrick Mission Church

St. Patrick Mission Church

San Antonio Chapel

San Antonio Chapel

San Agustín Church

San Agustín Church

San Antonio de la Ladera Chapel

San Antonio de la Ladera Chapel

Santuario de Chimayó Chapel

Santuario de Chimayó Chapel

San Acacio Mission Church

San Acacio Mission Church

The photographs included in this Constellation were taken during the research for Frank Graziano’s book Historic Churches of New Mexico Today, which will be released by Oxford University Press on April 1, 2019. Hundreds of additional photographs from the project’s fieldwork are available to researchers at the University of New Mexico’s Center for Southwest Research in Albuquerque.

***

The architecture of New Mexican village churches is often described as vernacular, which is to say that the construction materials (adobe, stone, vigas, latillas) are local; the design reflects local taste, tradition, and resources; the construction standards are idiosyncratic, pursuant to the experience, inclinations, and skills of the builders; and the finished product represents the history and cultural identity of the community.1 In broad view the style of the adobe churches is an adaptation of Pueblo Indian building methods to Spanish and Franciscan technologies, designs, and religious purposes.

San Francisco in Ranchos de Taos, completed around 1815, is one of the outstanding accomplishments of this tradition. The apse has massive buttresses and a sculptural quality that has been interpreted by a roster of photographers and painters. Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, Laura Gilpin, and Georgia O’Keeffe are perhaps the most prominent, but other artists include members of the Taos Society of Artists in the early twentieth century and the amateur photographers who now capture the image daily.

The intrigue is largely a response to the anomaly of the buttresses. As George Kubler already recognized in 1940, “the function of the buttressing could be satisfied with less material in more commonplace shapes” and “the buttressing seems to satisfy certain formal rather than structural needs.”2 The purpose of the buttresses, that is to say, seems more aesthetic than functional, and the apse has the feel of an enormous folk art sculpture. This aesthetic value is further enhanced by the imperfections, curved corners, soft lines, undulations, changing shadows, mud cracks, perching birds, and the fringe of rocks that keep parked cars from getting too close. The apse is voluminous and rustic but also graceful, with a sense of harmony to its disproportion.

Another quality is the church’s relation to the earth of which it is made. As Ansel Adams put it, “The massive rear buttress and the secondary buttress to the left are organically related to the basic masses of adobe, and all together seem an outcropping of earth rather than merely an object constructed upon it.”3 The church seems more emerging from the earth than superposed on it, and the effect of this earth/sculpted-earth coherence recalls Aristotle’s idea that art completes nature. The organic integration also extends to the church’s environs—the plaza, the sky—which seem part of the composition. The plaza and the sky serve as a kind of niche into which the church is situated, and that situation—together with the history and cultural knowledge that we bring to our viewing—provide a sense of completion in which the church’s beauty is fully realized.4 As one scholar put it, in a separate context, “the space around the sculpture is part of that sculpture.”5

This effect is particularly apparent when we view an isolated rural church. The sculpture (church) and the backdrop (landscape, silence) seem to fuse into a single perceptual experience. The continuity of church and landscape together commands our attention subtly with its serenity. Ruins also have this sculptural quality, especially when they are stone. The abandoned buildings seem giant sculptures against the dramatic backdrops of sky, mountains, deserts, cliffs, and valleys. Symbolic values tend to consolidate on such buildings—churches, ruins—but even landscapes are repositories for histories, memories, and cultural meanings. When we look across a valley we may see only grass, trees, cows, and distant mountains, but superimposed over the scenery are the invisible layers of centuries of everyday experiences, subsistence struggles, joys and sorrows, good times and hard times, traditions and rituals that are imperceptible but cognitively present. Our knowledge of a place’s past informs what we see presently and contributes to our emotional response.

The aesthetic appeal of adobe churches is also affected by synesthesia (the mixing of sense perceptions). The surface of the adobe seems at once visual and tactile, with a visual sense of texture and—paradoxically—smoothness. The solidity seems not rigid but rather soft and malleable, with a swell, and sometimes gives the impression that it might be pliant and yielding to the touch. We perceive the church’s volume and mass, its weight, as these come through the sueded surface and visual warmth. The holiness and devotion inside emanate outward, not perceptibly but cognitively through the knowledge and sometimes faith that is inherent in perceptions.

Villagers adapt the most fundamental resource—dirt—into homes and churches when they build with adobe, and human imagination thereby molds the external world along the contours of an internal sense of culture-in-place. This is how the world we build should look as it conforms to who we are and the knowledge and skills and aesthetic by which we adapt resources to our purposes. The emotions and attachments that people feel toward their churches are not evoked by a building’s physical presence alone, however pleasing it might be, but also by each church as the locus and repository of the investments made there, of the meaningful personal and communal experiences based there, and of the presences, including divinity, represented there.

- 1Vigas are ceiling beams made from debarked tree trunks and latillas are saplings, branches, willow, or split cedar arranged above and across the beams, at right angles or in diagonal patterns. The roof is completed and the ceiling is insulated by a layer of dirt above the latillas.

- 2George Kubler, The Religious Architecture of New Mexico in the Colonial Period and Since the American Occupation (Colorado Springs: The Taylor Museum, 1940), 45.

- 3Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (New York: Little, Brown, 2004), 91.

- 4Regarding the sculpture in the niche of its surroundings, I am following Rainer Maria Rilke in F. David Martin, Sculpture and Enlivened Space (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1981), 185.

- 5Martin, Sculpture and Enlivened Space, 28.

San Antonio was built around 1930 in Alamillo, a village of the southern Río Grande valley. The church is a mission of San Miguel parish in Socorro.

Permission to build Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria, known today as Our Lady of Purification, was given in 1844, after the Doña Ana Bend Colony land grant was finalized in 1843. The church was expanded in the early 1860s and was comprehensively restored between 1987 and 1999. The town where Our Lady of Purification is located, Doña Ana, is about five miles north of Las Cruces.

Immaculate Conception, in the town of Casa Colorada, is a mission of the Tomé parish by the same name. The church was built in 1949 with a design reminiscent of earlier constructions.

St. Augustine is located in Isleta Pueblo, about fifteen miles south of downtown Albuquerque. It was first built as a Franciscan mission in 1612-1613 and dedicated to San Antonio de Padua. The church was burned during the Pueblo Revolt in 1680, rebuilt after 1710 by incorporating what remained of the original structure, and rededicated to St. Augustine. The current church is the result of a comprehensive, sixteen-month restoration that was completed in 2011.

San Rafael is located in the Mora County village of La Cueva. The church was originally built between 1862 and 1870 under the direction of a French priest, Father Jean-Baptiste Guérin. The French influence made San Rafael unique among the adobe churches of the region, with gothic windows, a high ceiling, and an upward elegance. The church was comprehensively restored in the 1990s.

San Francisco de Asís, in the former mining town of Golden, was built in the 1830s, restored or rebuilt on the original foundation around 1918, and redesigned and again restored by Fray Angélico Chávez in the early 1960s. Decades later, after the town had been largely depopulated and the church had fallen into disrepair, a local family saved the church from ruin with volunteer labor and donated materials.

Santa Rosalía, in the foreground, is located in the village of Moquino, near Laguna Pueblo. The structure behind the church is the village’s Penitente morada.

San Isidro chapel, completed in 1952, is in Taos.

The apse of San Francisco in Ranchos de Taos has massive buttresses and a sculptural quality that has been interpreted by a roster of photographers and painters, notably Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, Laura Gilpin, and Georgia O’Keeffe. Annually during the first two weeks of June the church is resealed with adobe mud by parishioners and volunteers. San Francisco was originally completed around 1815.

St. Patrick was built in the early 1930s on the Mescalero Apache reservation, near Three Rivers. The construction was initiated and directed by a Franciscan, Father Albert Braun, who also built St. Joseph Apache Mission in Mescalero.

San Antonio is located in a rural area known as El Macho, about seven miles north of Pecos. The one-room sandstone chapel, covered now with stucco, was probably built in the mid-nineteenth century.

San Agustín (also spelled Augustin and Augustine) is a mid-nineteenth-century church located in a mostly depopulated village in the Gallinas River valley south of Las Vegas, New Mexico.

San Antonio de la Ladera is a hilltop family chapel accessed by a rugged stairway, in Chimayó.

The Santuario de Chimayó is a major international pilgrimage site. The chapel is flanked on the left side by a room of votive offerings that leads to a pocito, where holy dirt is gathered.

San Acacio in the village of Golondrinas is one of the sixteen mission churches of St. Gertrude Parish in Mora.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.con.2019.1

1. Frank Graziano, "Adobe and Stone Churches of New Mexico: A Selection," Constellation, MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 1 (2019), doi:10.22332/mav.con.2019.1

Graziano, Frank. "Adobe and Stone Churches of New Mexico: A Selection." Constellation. MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 1 (2019). doi:10.22332/mav.con.2019.1