Raúl Montero Quispe is a professional photographer and graphic designer in Cuzco who has studied History at the National University of San Antonio Abad of Cuzco. He worked for more than five years as collections photographer for the Archbishopric of Cuzco. He has won various awards for his photography. His work has been included in numerous research publications about Peruvian material and immaterial cultural heritage. He is currently Digital Content Developer for MAVCOR.

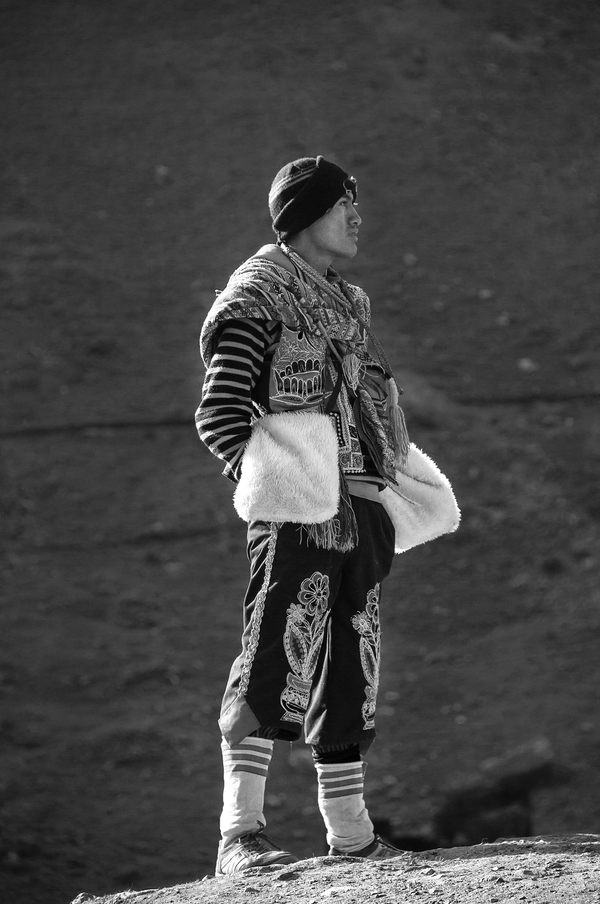

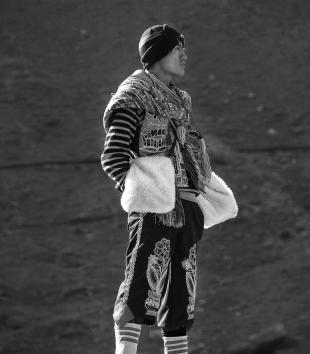

Maqta

Maqta

Pasñas of Ausangate/Pasñas del Ausangate

Pasñas of Ausangate/Pasñas del Ausangate

Finally the Snow!/Por fin ¡La Nieve!

Finally the Snow!/Por fin ¡La Nieve!

Ukukus rendering tribute to the cross and the mountain/Ukukus rindiendo tributo a la cruz y la montaña

Ukukus rendering tribute to the cross and the mountain/Ukukus rindiendo tributo a la cruz y la montaña

From father to son . . ./De padre a hijo . . .

From father to son . . ./De padre a hijo . . .

Qapac Qollas render homage to the cross and the mountain/ Qapac Qollas rinden homenaje a la cruz y la montaña

Qapac Qollas render homage to the cross and the mountain/ Qapac Qollas rinden homenaje a la cruz y la montaña

First prayer of the day/Primera oración del día

First prayer of the day/Primera oración del día

Dance troupe of Capac Negros en route to the Sanctuary/Comparsa de Capac Negros de camino al Santuario

Dance troupe of Capac Negros en route to the Sanctuary/Comparsa de Capac Negros de camino al Santuario

Dance Troupe “Brothers Qapac Qolla of Cuzco”/Comparsa “Hermanos Qapac Qolla del Cusco”

Dance Troupe “Brothers Qapac Qolla of Cuzco”/Comparsa “Hermanos Qapac Qolla del Cusco”

Family from Ausangate/Familia del Ausangate

Family from Ausangate/Familia del Ausangate

A Cusqueña girl on Sinaqara/Cusqueñita en el Sinaqara

A Cusqueña girl on Sinaqara/Cusqueñita en el Sinaqara

Rest on the ascent to Sinaqara/Un descanso en el ascenso al Sinaqara

Rest on the ascent to Sinaqara/Un descanso en el ascenso al Sinaqara

Heading to Sinaqara/Rumbo al Sinaqara

Heading to Sinaqara/Rumbo al Sinaqara

Standard Bearer/Porta Estandarte

Standard Bearer/Porta Estandarte

Waiting for the first rays of the sun/Esperando los primeros rayos del sol

Waiting for the first rays of the sun/Esperando los primeros rayos del sol

Waiting for the others/Esperando a los demás

Waiting for the others/Esperando a los demás

The reststop at Cinajara/La posada del Cinajara

The reststop at Cinajara/La posada del Cinajara

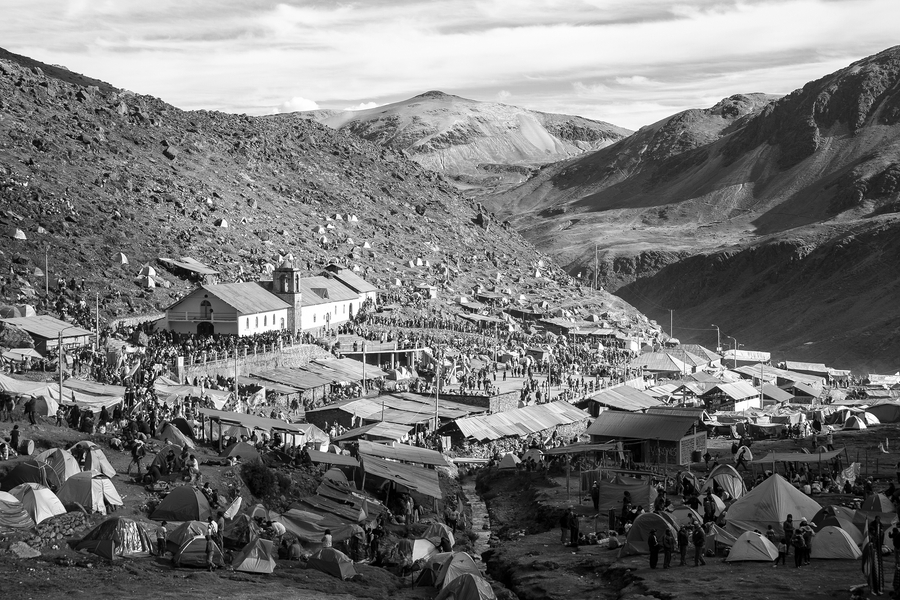

The Sanctuary during the festival/El Santuario durante la festividad

The Sanctuary during the festival/El Santuario durante la festividad

4972 meters above sea level/4972 msnm

4972 meters above sea level/4972 msnm

The Sanctuary and the Guardian/El Santuario y el Celador

The Sanctuary and the Guardian/El Santuario y el Celador

Prayer for those who are not among us/Oración por los que ya no estan entre nosotros

Prayer for those who are not among us/Oración por los que ya no estan entre nosotros

An artist’s statement accompanying the photographic project Qoyllur rit’i: The Lord of the Snow Star. Translated from the original Spanish by Emily C. Floyd. Versión en español disponible aquí.

The festival of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i, the “Lord of the Snow Star” in Quechua, is an important pilgrimage in the southern Peruvian Andes to the sanctuary of the same name at the base of the snow-capped mountain Sinakara, more than 4600 meters above sea level in the Cuzco region. Every year in the months of May and June, depending on the date of Lent, thousands of pilgrims from the most remote regions of the southern Peruvian Andes congregate at the site. Fortified by their devotion and faith, they confront high altitudes and extreme temperatures in a steep upward climb of more than eight kilometers.

The origins of the festival may extend back to before the arrival of Europeans in the region, but it is with the coming of the Spaniards and syncretic Catholicism that Qoyllur rit’i acquired the form and scale of today’s event. In the pilgrimage, ancestral rites converge and often overlap with Catholic traditions centered on a rock displaying a miraculous painting of the crucified Christ. The festival and sanctuary were declared Patrimonio Cultural de la Nación (National Cultural Heritage) in 2004 by the Peruvian state. In 2011 UNESCO listed the pilgrimage as Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The first time I went to the sanctuary was in 2001, when the paved highway that now connects the Cuzco region with the Peruvian jungle was not yet in existence. My memory is of a long, cold, and dusty journey by truck with a group of dancers who sang songs in Quechua and Spanish throughout the trip. Back then I was part of the Catholic school that organized the excursion, and I didn’t understand much of what was going on. On my second visit in 2006, I went with devout family members, a few days after the main festival. I found the route and sanctuary practically empty and for the first time I had the opportunity to approach the miraculous rock. From then on, until 2018, I returned to the sanctuary on various occasions. On each trip, I was fascinated by the spectacle, the rituals, and everything related to this festival, a festival which I was only beginning to understand.

In 2012, I began to make a graphic record of the pilgrimage, which little by little evolved into a photographic project. In this project, my interest in the complexity of the festival, beyond its veil of Christianity, increased, and I began to investigate beyond what my Catholic beliefs had taught me. In attempting to comprehend the syncretic world of the festival, photography allowed me to capture and narrate what I saw.

In 2018 I made my most recent visit to the sanctuary, a visit which in some ways represented the culmination of my modest photographic project. On this occasion, I traveled with “Hermanos Qapac Qolla del Cusco,” a comparsa or group of dancers who wear regional costumes and dance as a form of devotion in honor of a specific image of the Virgin, Christ, or a saint. In contrast to my previous trips, I was able to experience the traditional three days of the pilgrimage together with the comparsa, as just another member of the group. The photographs I took on this pilgrimage accompany this text. These written reflections convey what I have learned and observed in my repeated visits to the Sanctuary of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i.

Origin of the Tradition

The tradition as it is known today has its origins in a miraculous story, which the more experienced pilgrims relay to the newer ones, a story based in accounts from the mid-twentieth century, but with the earliest sources dating the miracle to between 1780 and 1783.1 A mysterious “white” child appeared to Marianito Mayta, the young son of a shepherd from the town of Mahuayani, near the present location of the sanctuary of Qoyllur rit’i, and the starting point for the modern pilgrimage. The child played with Marianito and helped him care for the flock he was herding in the valley of Sinakara. After days of playing together, Marianito grew curious about his friend’s clothing, which never aged or got dirty, only to have his friend appear the next day with his clothing threadbare and torn. Marianito offered to travel to Cuzco to look for the necessary fabric to repair his new friend’s tunic, but when he went to the city he discovered that the cloth was of a kind reserved for the exclusive use of bishops. As such, according to the story, Marianito sought out the then bishop, Juan Manuel Moscoso y Peralta (1723-1811), to beg him for some fabric for his friend’s tunic. This petition caught the prelate’s attention. He accepted the child’s petition and sent a letter to the parish priest of the neighboring town of Ocongate asking him to investigate the matter.

According to the accounts, on June 12, 1783 the parish priest of Ocongate convinced Marianito to bring him to meet his friend. On reaching the valley, the priest was startled to see a child dressed in a tunic tending to the flock, but when he tried to approach him, the child began to emit a radiant light, hiding the child and forcing the priest to desist in his efforts. A few days later, this time accompanied by communal authorities, the priest returned to the place and tried again to approach the mysterious child, who once again emitted the radiant light. This time, however, the parish priest did not desist in his effort to capture the child, leading the child to flee to a pinnacle of rock, pursued by the priest and his party. Reaching the rock, they found that the light and the child had disappeared. In their place, the priest and the communal authorities discovered, in a tayanka bush, a shrub that grows at high altitude and is used for firewood by local inhabitants, a figure of the crucified Christ with blood in his wounds. According to the story, Marianito collapsed and died in the resulting commotion and was buried at the base of the rock. Later, the priest ordered that the miraculous apparition be excised from the tayanka bush and sent to the Church of Tayankani.2 A chapel was built around the pinnacle of rock where the child disappeared, upon which, according to the miracle accounts, an image of Christ Crucified had also appeared, which the parish priest subsequently contracted a painter from Cuzco to “touch up.” As the news of the miraculous apparition of the image spread, the first pilgrims began to come to the site. This chapel would become what we know today as the Temple of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i, a holy place and central focal point of the pilgrimage.

- 1Imelda Vega-Centeno B., “Relatos sobre el origen de los cultos del período interequinoccial en la región del Cuzco,” Revista andina 47 (2018): 83-115.

- 2In the church of Tayankani, close to the town of Ocongate, and itself the starting point of “the 24-Hour Procession” that forms part of the pilgrimage, there is a carving of the crucified Christ. According to the faithful, this image is a copy of the one that the parish priest found. The mobile image of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i that goes out in processions from the sanctuary is likewise understood to be a copy of the original found in the tayanka bush. The legend says that the bishop sent the image of Christ found in the tayanka bush to Spain to a king generally identified (anachronistically) as Charles V in order to verify the miracle, but that the tayanka image was never returned to the Andes, and so a copy was made for the church. The name of the church, Tayankani, is Quechua for “I am from tayanka.”

Sacred Space

Like many sacred spaces in the Andes, the sanctuary is situated near one of the Apus or sacred mountains of the city of Cuzco, in this case Mt. Ausangate. The sanctuary is located in a narrow glacial valley at the foot of the snow-capped peak called Sinakara. The modern construction that houses the rock of the apparition is located at 4700 meters above sea level; nothing remains of the original building. The modern building is a cement structure with a tin roof. An enormous stairway at its entrance leads to an atrium of generous dimensions, in which various comparsas dance day and night for the three days of the celebration. In the surrounding area of the valley, pilgrims set up plastic tents to pass the night, although the majority prefer to sleep in the open air, wrapped in sleeping bags or traditional regional woven blankets, just as the generations that preceded them did. At the entrance of the sanctuary and in the lower part of the temple, vendors in multicolored plastic stalls offer a wide range of religious products together with alasitas, miniature objects whose ritual purpose is to convert wishes in reality. It is also possible to find stands where all kinds of food and beverage are sold, with the exception of alcoholic beverages, which are not offered, at least officially.

The Route

There are two pilgrimage routes: the first, which may preserve traces of a pre-contact route predecessor to the modern Catholic one, is called the “24-Hour Procession.” It begins at the Church of Tayankani, in Ocongate, and winds along a path of gullies and plateaus. According to Constanza Ceruti, there is evident syncretism in the rituals practiced at specific geographic points.1 The second route, which is shorter and more trafficked in the present day, is the route I took in all my visits to the sanctuary. This route begins at the town of Mahuayani, following a steep road of more than 8 kilometers divided into a via crucis of fourteen stops, which are used as places of rest and prayer. The route starts out narrow at the beginning and widens as it enters the valley, following the sinuous curve of the stream that emerges from the glacier. This path can be taken on foot or by horse, although in recent years, as I was able to observe in my last visit, the horses are being replaced by motorcycles. The two potential starting points can be reached via bus and truck from the city of Cuzco, a 150-kilometer trip that lasts 5-6 hours along the interoceanic highway that unites the region of Cuzco with the Peruvian jungle.

- 1María Constanza Ceruti, “Qoyllur Riti: etnografia de un peregrinaje ritual de raiz incaica por las altas montañas del Sur de Peru,” Scripta Ethnologica 29 (2007): 9-35.

The Pilgrims

The pilgrims hail from many places, but the majority are Indigenous Quechuas and mestizos from the valleys of the region of Cuzco, although there is also an important presence of Aymara peoples from the Lake Titicaca basin, as well as residents of the city of Lima. More recently, there has also been a confluence of foreign pilgrims coming from Argentina, Chile, and Bolivia, as well as a smaller number of Europeans and North Americans motivated by adventure and “mystic” tourism. Mystic and adventure tours to Qollyur rit’i are marketed in Cuzco as packages to tourists.

The vast majority of the pilgrims are part of a comparsa, which can be small or large. These comparsas are integrated into the eight “nations” of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i. The word “nation” refers to groupings of comparsas representing one of the regions of Cuzco. The comparsa Hermanos Qhapaq Qolla del Cusco (Brothers Qhapaq Qolla of Cuzco), for instance, belongs to the nation of Tahuantisuyo, representing the city of Cuzco. Each comparsa has a carguyoq, called “mayordomos” in Spanish, who are the organizers and managers responsible for all the preparations for the pilgrimage, as well as the comfort and well-being of the pilgrims during the festival. They cover the costs demanded by the pilgrimage in exchange for celestial favors, and generally march at the front of their respective groups carrying the apuyaya, a kind of relic or standard with the image of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i. The election of the carguyoc takes place annually from among the most influential of the pilgrims in a solemn ceremony at the base of Sinakara. Additionally, each comparsa has a quimichu or guardian of traditions. In the comparsa that I accompanied, our quimichu was responsible for making the stops and offerings along the path. One of the rituals that the quimichu oversaw consisted of carrying a rock of the size that we considered equivalent to our sins from one station of the via crucis to the next, until we reached Cruzpata, the last station of the via crucis. This final station is a very emotional, because it is from there that one can first see the sanctuary.

The social status of the pilgrims is very diverse, but the majority are low- and middle-class peasants, businesspeople, and entrepreneurs. Such was the case with the comparsa Hermanos Qhapaq Qolla del Cusco, the majority of whom were businesspeople from the city of Cuzco.1 Members of comparsas are easy to recognize at the site as, in contrast with spontaneous pilgrims, or “visitors” as they are called, members of comparsas wear traditional regional costumes, and make the ascent carrying everything the need for the three days of the celebration on their backs, including blankets, foodstuffs, and firewood. In my case, I helped out by carrying some pieces of firewood.

- 1The name of the comparsa also alludes to the occupation of its members, because in Andean tradition the Qhapaq Qolla were businesspeople from the Andean high plateau (altiplano).

The Development of Ritual in the Sacred Space

Like all the pilgrims arriving at the sanctuary, even before setting up camp we went immediately to visit the church and offer homage to the crucified Christ of the rock with a few brief songs and dances. This was the preface to three days of continual celebration whose mystic essence was the invocation of the Christ of brilliant snow, pagos (payments) or offerings to the Apus, various signs of respect towards the sacred rock in the church, and processions to a small chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. All of these rituals are accompanied by the continuous dances performed by the comparsas of the various nations.

At daybreak, in a ritual thought to preserve some link to the pre-contact sun cult of the Incas, the comparsas form lines, waiting for the emergence of the sun.1 The quimichu, lifting his arms towards the east, makes supplication in Quechua and Spanish, a mix of Christian prayers and petitions to the Apus, while the rest of the members of the comparsa kneel as a sign of respect. This act tends to be accompanied by the playing of pututus, large marine conch shells known as “Andean trumpets.” As our comparsa was small we did not have pututus in our ceremony, but we heard the sound of the Andean trumpets of the other comparsas. Following the prayers of the quimichu, we paused silently out of respect for those who are no longer among us, before wishing each other mutually “Wataskama” (“until next year”).

- 1The sun was one of the Incas’ principal deities, to whom they particularly dedicated rituals at the time of year coinciding with the winter equinox in the southern hemisphere, the same period as the festival of Qoyllur rit’i.

Once the sun begins to radiate across the sanctuary, the unending dances begin, as do the processions to various religious objects and sites scattered throughout the sacred space, including crosses, niches, altars, or spaces that house a devotional object. But the principle place for offering devotion is always the temple, where the comparsas, including Hermanos Qhapaq Qolla del Cusco take turns parading and dancing before the sacred image of the rock. From what I observed, and later confirmed in research, dance is the principal form of devotion that the devotees offer, alongside ritual flagellation and exhaustion.1

- 1Ceruti, “Qoyllur Riti.” This pattern mirrors that of other Christian devotions in the Andes.

The sacred space of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i is also the setting for offerings or pagos made to the Apus or mountain spirits. Within Andean cosmovision, nature, and runas, or people, are complementary and constitute a whole. Entities like the Pachamama (mother earth) are considered ensouled and spirited living beings. Andean people do not dominate the natural environment, but rather live and coexist with her. The ritual of the pago symbolically returns in an act of reciprocity all that has been produced in collaboration with the earth, invoking at the same time blessings for future harvests.

The pinnacle of these celebrations takes place when the ukukus, personages dressed in warm black tunics of wool with long a fringe and a waqollo or ski mask on their head that mimics the appearance of Andean bears, climb up to the glacier. There they perform rituals in honor of the mountain, including initiation rites which consist of the flagellation of new members. Until 2001, the ukukus returned carrying enormous blocks of ice as offerings, which were blessed in the temple to then be carried back to the ukukus’ communities so that they could water their fields and animals with the blessed water. Due to global warming, however, the Confraternity of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i prohibited this ritual. Today the ukukus return only with small bottles of water from the glacier. On a symbolic level, the ukukus are the mediators between humans and the sacred world of the high mountain peaks.

Among other rituals that accompany the celebrations is the ludic, fictitious purchase and sale of alasitas. These are sold in the place known as Pukllanapata, or place of play, located close to the chapel of the Virgin. Devotees also collect wax from the candles of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i as a kind of relic. The festival ends with a great mass of blessing, and the devotees return from there to Cuzco, to join the city’s great festival of Corpus Christi.

A Photographer’s Perspective

As a photographer, I normally prefer to present my photographs in color, but, on this occasion, I chose to have the final images printed in black and white when the project was exhibited in 2020-2021 as part of the Religion in the Andes exhibition at the Institute of Sacred Music, Yale University. In addition to honoring the solemnity that is part of the traditional photographic process, I also wanted to convey the sacred atmosphere that is pervasive in everything that surrounds this festival and in the physical space of the pilgrimage, without the distraction of color. From my perspective, the colors of the original images intoxicate the gaze, pulling the viewer’s attention away from the sense of the sacred that draws thousands of people each year from the most diverse regions of the Andes, to brave the high altitudes and extreme temperatures in a pilgrimage as unique as the landscapes that serve as its backdrop.

Through the photographic project, as well as this text that now accompanies it, I wish to leave a testimony of my lived experience and of the small changes I have witnessed over time. I hope I have conveyed what I have learned and come to understand in visits to the Sanctuary of the Lord of Qoyllur rit’i over the past decade.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.con.2021.1

1. Raúl Montero Quispe, "Qoyllur rit’i: The Lord of the Snow Star," Constellation, MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 2 (2021), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2021.1

Montero Quispe, Raúl. "Qoyllur rit’i: The Lord of the Snow Star." Constellation. MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 2 (2021), doi: 10.22332/mav.con.2021.1