Emily C. Floyd is Lecturer of Visual Culture and Art before 1700 at University College London and Editor and Curator at the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Culture of Religion at Yale University (MAVCOR). Her current research centers on normative whiteness, implicit depictions of race, and intersecting ideas of sanctity, monstrosity, and the body in colonial South America. Her book on prints made in colonial Lima and their regional and transatlantic impact, The Mobile Image: Prints from Lima in the Andes and Beyond, 1584-1824 is forthcoming in 2025 from University of Texas Press.

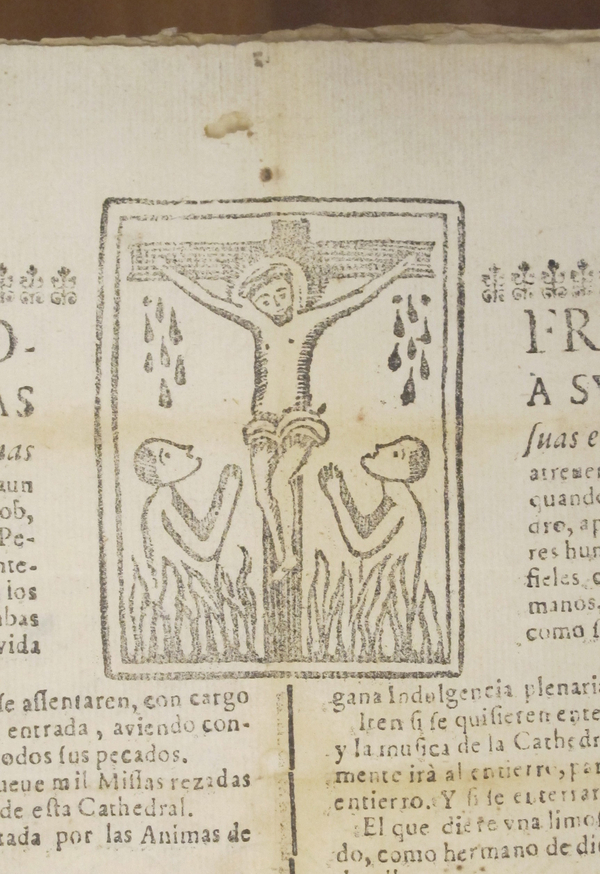

A simple woodcut on a late-seventeenth-century membership letter of the confraternity of Souls of the Cathedral of Lima presents a straightforward narrative. The woodcut depicts two souls bathed in flames, gazing up at Christ crucified. Stylized drops of blood pour from each of Christ’s wounded hands, cascading in the direction of the souls’ uplifted faces. The woodcut droplets visually embody the doctrinal logic behind indulgences—the great sacrifice of Christ and of the martyrs of the church created a treasury of merit that ordinary sinners could draw upon. By joining a confraternity, you entered into a contract: your financial commitment in exchange for your soul’s relief after death.

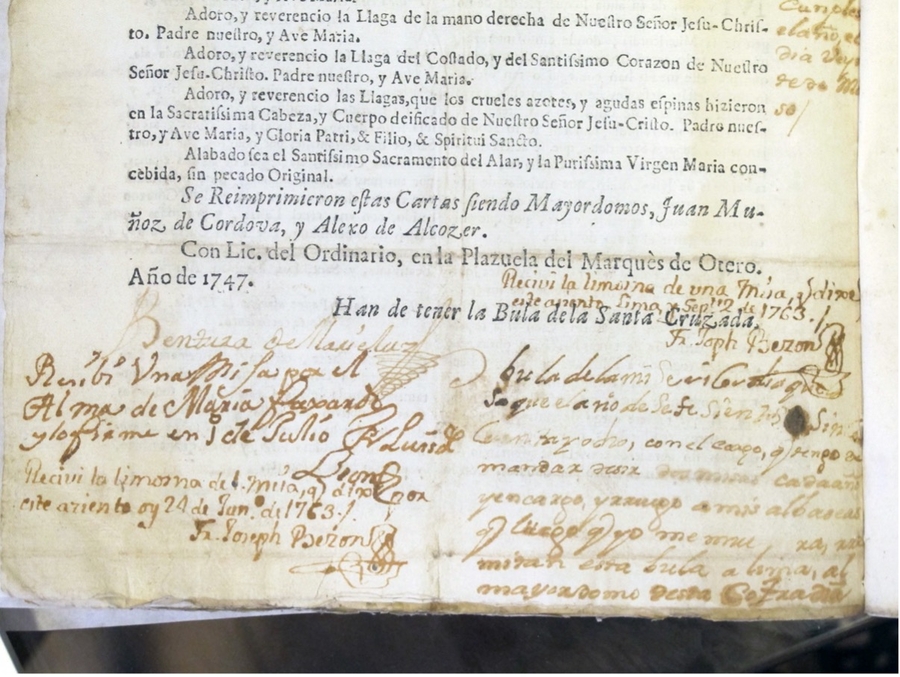

In colonial Lima, lay confraternities printed letters certifying membership and listing the material and immaterial benefits of joining, typically consisting of funerary insurance and indulgences. Confraternal letters materialized contractual bonds that extended across colonial geographies and reached into the ambiguous in-between realm of temporary suffering that was purgatory. Scrawled handwritten notes tersely list the name of the new member, the date, and the signature of a confraternal official. Occasionally they offer more information: an 1802 letter dissolved the confraternity’s link to one of its members “Given that this brother even before he joined suffered from emission of blood from the mouth.” You could not join a confraternity promising funerary insurance if you were already at death’s door.

Other letters reveal the endurance of confraternal links. Maria Faxardo, resident of the northern coastal town of Trujillo, joined the Lima Confraternity of the Virgin of Misericordia in 1758. On her letter, Faxardo committed to having two masses said each year for her confraternal siblings and added, “I plead of my legal executors that once I have died they remit this bull to Lima” so that her soul could benefit from the promised masses said in her honor. Her executors carried out her will: additional notes added to the letter include the signatures of three Augustinian friars who said masses for her soul in 1763 in Lima after her death.

Notes

Imprint

Author

Emily C. Floyd

Year

2022

Type

Object Narratives

Volume

Volume 6: Issue 3 Characterizing Material Economies of Religion in the Americas

Copyright

©

Emily C. Floyd

Licensing

Downloads

PDF

DOI

10.22332/mav.obj.2022.12

Citation Guide

1. Emily C. Floyd, "Confraternal Letter," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.12.

Floyd, Emily C. "Confraternal Letter." Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 6, no. 3 (2022), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2022.12.