Carolina Sacristán-Ramírez, Ph.D. is an art historian specializing in devotional art and music from Colonial Latin America. She is also a harpsichord player.

Paintings are silent, but not to those who know how to listen. Some paintings appeal to the sense of hearing in order to stimulate the beholder’s emotional engagement. This article explores the symbolism of music and silence, and conjures the aural atmosphere of female devotion in the eighteenth-century Viceroyalty of Peru by analyzing two artworks in the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Collection: The Nativity with Musical Angels and The Sleeping Christ Child with the Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (Figs. 1 and 2).1 These images communicate theological concepts and convey emotions through a dense fabric of symbols. Music plays a decisive role in relation to these paintings; it provides insights into the significance of the images that would otherwise remain hidden. I argue that, for eighteenth-century nuns living in the Viceroyalty of Peru, both paintings evoked a particular kind of religious music: Latin polyphony or villancicos (part-songs in the vernacular, which were performed in sacred contexts).2 The depiction of music or silence enhances the emotional core of each work: vocal and instrumental music promote an outward and joyful religiosity associated with the birth of Christ; silence encourages an intimate reflection on the suffering of his future Passion. This intention can be appreciated in the villancicos that were composed as a sort of lullaby for the baby Jesus.

We do not know much about the history of either painting, but their dimensions suggest that they were meant for private religious practices. In colonial Latin America, small images representing the Christ child were commonly placed in altars designated for individual worship inside homes and within nuns’ cells in women’s monastic communities.3 Devotional chapbooks instructed devotees to kneel before such paintings while reciting their daily prayers.4 Brianna Leavitt-Alcantara has shown that women in colonial Central America tended to pay particular attention to these sorts of images in their wills, especially those depicting the birth of Jesus. They bequeathed them to other women (whether they were nuns, relatives, or servants) resulting in gender-specific devotional networks.5 Convents, such as Santa Catalina and Santa Teresa in Arequipa, possess significant collections of paintings and statues of the sleeping infant Christ, as well as large-scale, extensively populated nativity scenes, all suggestive of nuns’ devotion to the infant Christ (Figs. 3 and 4). It has additionally been argued that images of the Christ child were often the personal property of women because they appealed to their supposedly natural attachment to children. However, this assertion must of course be viewed within the context of the patriarchal nature of colonial society.6 Nonetheless, given the evidence for female attachment to and engagement with small paintings of the child Jesus, it seems likely that the two paintings in the Thoma Collection were intended to serve as devotional tools for women.

- 1This research has been generously supported by Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation, the Blanton Museum of Art and LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections. I extend my sincere gratitude to the readers who provided feedback on an earlier version of this article.

- 2Tess Knighton and Álvaro Torrente, Devotional music in the Iberian world, 1450-1800: the villancico and related genres (Farnham: Ashgate, 2007), 3.

- 3Sara T. Nalle, “Private Devotion, Personal Space. Religious Images in Domestic Context,” La imagen religiosa en la Monarquía hispánica. Usos y espacios , ed. María Cruz de Carlos Varaona (Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, 2008), 264-265.

- 4See, for instance, Novena de la milagrosa imagen del Niño Jesús peregrino (México: Felipe Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1776), 2. Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, Fondo Toribio Medina, III-44A-C25(29).

- 5Brianna Leavitt-Alcantara, “Practicing Faith: Laywomen and Religion in Central America, 1750-1870” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2009), 90-92. See also Brianna Leavitt-Alcántara, Alone at the Altar: Single Women and Devotion in Guatemala, 1670-1870 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2018).

- 6Nalle, “Private Devotion,” 265. On the experiences of women within patriarchal colonial society, see Susan Midgen Socolow, The Women of Colonial Latin America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Asunción Lavrín, Las mujeres latinoamericanas: perspectivas históricas (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985).

Paintings are silent, but not to those who know how to listen. Some paintings appeal to the sense of hearing in order to stimulate the beholder’s emotional engagement. This article explores the symbolism of music and silence, and conjures the aural atmosphere of female devotion in the eighteenth-century Viceroyalty of Peru by analyzing two artworks in the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Collection: The Nativity with Musical Angels and The Sleeping Christ Child with the Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph, and the Infant Saint John the Baptist (Figs. 1 and 2).1 These images communicate theological concepts and convey emotions through a dense fabric of symbols. Music plays a decisive role in relation to these paintings; it provides insights into the significance of the images that would otherwise remain hidden. I argue that, for eighteenth-century nuns living in the Viceroyalty of Peru, both paintings evoked a particular kind of religious music: Latin polyphony or villancicos (part-songs in the vernacular, which were performed in sacred contexts).2 The depiction of music or silence enhances the emotional core of each work: vocal and instrumental music promote an outward and joyful religiosity associated with the birth of Christ; silence encourages an intimate reflection on the suffering of his future Passion. This intention can be appreciated in the villancicos that were composed as a sort of lullaby for the baby Jesus.

We do not know much about the history of either painting, but their dimensions suggest that they were meant for private religious practices. In colonial Latin America, small images representing the Christ child were commonly placed in altars designated for individual worship inside homes and within nuns’ cells in women’s monastic communities.3 Devotional chapbooks instructed devotees to kneel before such paintings while reciting their daily prayers.4 Brianna Leavitt-Alcantara has shown that women in colonial Central America tended to pay particular attention to these sorts of images in their wills, especially those depicting the birth of Jesus. They bequeathed them to other women (whether they were nuns, relatives, or servants) resulting in gender-specific devotional networks.5 Convents, such as Santa Catalina and Santa Teresa in Arequipa, possess significant collections of paintings and statues of the sleeping infant Christ, as well as large-scale, extensively populated nativity scenes, all suggestive of nuns’ devotion to the infant Christ (Figs. 3 and 4). It has additionally been argued that images of the Christ child were often the personal property of women because they appealed to their supposedly natural attachment to children. However, this assertion must of course be viewed within the context of the patriarchal nature of colonial society.6 Nonetheless, given the evidence for female attachment to and engagement with small paintings of the child Jesus, it seems likely that the two paintings in the Thoma Collection were intended to serve as devotional tools for women.

- 1This research has been generously supported by Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation, the Blanton Museum of Art and LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections. I extend my sincere gratitude to the readers who provided feedback on an earlier version of this article.

- 2Tess Knighton and Álvaro Torrente, Devotional music in the Iberian world, 1450-1800: the villancico and related genres (Farnham: Ashgate, 2007), 3.

- 3Sara T. Nalle, “Private Devotion, Personal Space. Religious Images in Domestic Context,” La imagen religiosa en la Monarquía hispánica. Usos y espacios , ed. María Cruz de Carlos Varaona (Madrid: Casa de Velázquez, 2008), 264-265.

- 4See, for instance, Novena de la milagrosa imagen del Niño Jesús peregrino (México: Felipe Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1776), 2. Biblioteca Nacional de Chile, Fondo Toribio Medina, III-44A-C25(29).

- 5Brianna Leavitt-Alcantara, “Practicing Faith: Laywomen and Religion in Central America, 1750-1870” (PhD diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2009), 90-92. See also Brianna Leavitt-Alcántara, Alone at the Altar: Single Women and Devotion in Guatemala, 1670-1870 (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2018).

- 6Nalle, “Private Devotion,” 265. On the experiences of women within patriarchal colonial society, see Susan Midgen Socolow, The Women of Colonial Latin America (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015); Asunción Lavrín, Las mujeres latinoamericanas: perspectivas históricas (México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1985).

Women and the Sense of Hearing

Women not only owned this kind of painting, but their engagement with them would have been understood in the colonial period to have been inflected by gendered experiences of the senses. Both the Spaniards and the Incas who preceded them in the Andes conceived of vision and hearing, the same senses which I argue The Nativity and The Sleeping Christ Child emphasize, as the senses that dominated human experience of the world.1 The Incas, for example, characterized sound as the primary medium of creation, while light (corresponding to sight) was the element that allowed the world to acquire its definitive structure.2 The European model that predominated in the colonial period established a gendered hierarchy for the senses in which sight and hearing were not only the most important senses, but they were also considered “higher” or “rational” senses and thus associated with dominant groups like men. Smell, touch, and taste, in contrast, were considered “lower” or “corporeal” senses and thus aligned with subordinated groups like women.3 This classification system was not, however, entirely immutable. As Constance Classen observes, the major social divisions of gender and social class or condition could change the ascription of standard social hierarchies of perception; a woman—although linked to “lower” senses by tradition—might represent the “higher” senses if she, like the nuns in most of the important convents of colonial Cuzco, possessed the visual skills of reading and writing, or the auditory skills for music.4

According to Geoffrey Baker, beginning in the seventeenth century, musical performance and teaching were key elements of feminine convent life in Cuzco. In the Franciscan convent of Santa Clara in Cuzco, for example, the nuns devoted considerable effort to the study of music in order to ensure that both plainchant and polyphony with instrumental accompaniment were regular elements of their religious ceremonies.5 The quality of the music was so important that the nuns hired music teachers in order to cultivate exceptional singers and instrumentalists.6 Musical ability also had a significant financial value within the convent; it could bring privileges to the entire community and afford advantages of higher status for individuals.7 The abbesses were, therefore, willing to make generous offers to talented novices regardless of their ethnicity or social status.8 Contemporary religious witnesses widely appreciated nuns’ musical activities, such as musical-theatrical performances in church or private music making in the locutorios or visiting rooms of the convent.9 Other musical activities included the performance of villancicos and of traditional plainchant and Latin polyphony in the Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours. In contrast the seventeenth-century chronicles written by the Franciscan Diego de Mendoza, the Dominican Reginaldo de Lizárraga, and the Carmelite Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa indicate that music played a lesser role in male monastic communities.10 The Franciscan, Dominican, and Carmelite friars do not seem to have attributed the same importance to musical talent or training as the nuns.11

Music was a symbol of pride for both the city of Cuzco and its convents. It was also a means for the nuns to make known their presence in the urban environment and to establish their status through the “higher” sense of hearing.12 Music became a means of self-expression and affirmation for religious women in a male-dominated society.19 Nuns also appealed to hearing in order to achieve an aural imitation of the magnificence of heaven as they imagined it.13 Within a context where music was so relevant, the nuns would have commissioned or acquired devotional artworks with sonic elements, such as The Nativity or The Sleeping Christ Child, so as to incorporate music into their more intimate moments of spiritual reflection and meditation.

- 1Constance Classen, “Sweet Colors, Fragrant Songs: Sensory Models of the Andes and the Amazon,” American Ethnologist 17, no. 4 (1990): 722.

- 2Classen, “Sweet Colors,” 723, 725.

- 3David Howes, Empire of the Senses: The Sensual Culture Reader (Oxford: Berg, 2005), 10. Constance Classen, The Color of Angels: Cosmology, Gender and the Aesthetic Imagination (London: Routledge, 1998), 66.

- 4Classen, The Color of Angels, 68.

- 5Geoffrey Baker, “Music in the Convents and Monasteries of Colonial Cuzco,” Latin American Music Review 24, no.1 (2003): 4, 7.

- 6Kathryn Burns, Colonial Habits: Convents and the Spiritual Economy of Cuzco, Peru (Durham: Duke University Press, 1999), 106.

- 7Baker, “Music in the Convents,” 7. Juan Carlos Estenssoro, “Música y fiesta en los conventos de monjas limeñas, siglos XVII y XVII,” Revista musical de Venezuela 16, no. 34 (1997): 129.

- 8Antonia Viacha, an Indian novice in Santa Clara, who both performed and taught the bajón (dulcian—a woodwind instrument), was granted a reduction in her dowry when she took the white veil in 1708, Baker, “Music in the Convents,” 7. Doña Josefa María de Santa Cruz y Padilla, a talented singer, who was the niece and goddaughter of the Dean of the Cuzco cathedral, Alonso Merlo de la Fuente, was allowed to profess as “a nun of the white veil” without the payment of a dowry in 1676, Geoffrey Baker, Imposing Harmony: Music and Society in Colonial Cuzco (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2008), 111.

- 9Baker, “Music in the Convents,” 4-5.

- 10Diego de Mendoza, Chronica de la Provincia de San Antonio de los Charcas [1663] (La Paz: Casa Municipal de la Cultura “Franz Tamayo," 1976), 42-43. Reginaldo de Lizárraga, Descripción del Perú, Tucumán, Río de la Plata y Chile (Madrid: Historia 16, 1987), 111-114. Antonio Vásquez de Espinosa, Compendio y descripción de las Indias Occidentales (Madrid: Historia 16, 1992), 597. Baker quotes these sources in “Music in the Convents," 10-11.

- 11Baker, “Music in the Convents,” 10-11. Luisa Morales posits that the nuns saw their wealth dramatically diminished everywhere in Peru during the nineteenth century, as a result of the laws dictated by the various governments. In consequence, musical activity decreased too. Morales, “New Findings on Musical Activity and Instruments in the Convent of Santa Teresa, Cusco during the Colonial and Aristocratic Republican Periods,” in Música de tecla en los monasteries femeninos y conventos de España, Portugal y las Américas , coord. Luisa Morales (España: Asociación Cultural LEAL, 2011), 91-108.

- 12Baker, “Music in the Convents,” 5.

- 19Ibid.

- 13Estenssoro, “Música y fiesta," 129.

The Nativity with Musical Angels

The musical component of The Nativity with Musical Angels dominates the composition and immediately captures the viewer’s attention (Fig. 1). The canvas depicts baby Jesus at the manger with Mary, Joseph and a surrounding crowd of musical angels. Angelic choirs that praise and adore Jesus in the stable of Bethlehem constitute an old pictorial theme dating to the Byzantine period.1 In European Renaissance paintings, it is common to see a small group of angels singing and playing instruments close to the manger, although more elaborate ensembles of musician angels playing strings, woodwinds, brass, keyboard, and percussion instruments appear in artworks from Northern Europe representing the Virgin Mary nursing her child. In The Nativity, musician angels, positioned in two different registers occupy most of the pictorial space. The composition was copied from an engraving, probably by Hieronymus Wierix, originally included in the Office of the Blessed Virgin Mary published by Jan Moretus in 1609 in Antwerp (Fig. 5).2

- 1Amy Gillette, “The Music of Angels in Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Art," Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 6, no. 4 (2018): 26-78.

- 2Officium Beatae Mariae Virginis Pii V Pontifex Maximus iussum editum (Antuerpiea: Ioannem Moretum, 1609), 568, Biblioteca Histórica de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, BH FLL, 3908. Another painting based on the same engraving has been published by Ananda Cohen Suarez, Pintura colonial cusqueña. El esplendor del arte en los Andes (Cusco: Haynanka, 2015), 63.

In order to depict heavenly music on earth, the anonymous painter not only copied the Flemish engraving, but also incorporated some of the musical instruments he was probably accustomed to seeing every day. Thus, he replaced one of the lutes with a common harp and the shawm with an oboe. He also added a few additional percussion instruments. From the top left corner down and in counter-clockwise order, his ensemble comprises a triangle, an oboe, a drum, a bass violin, a harp and a lute of sorts. That is to say, a six-strong instrumental ensemble that accompanies a vocal trio. This vocal trio should potentially be understood as composed of two sopranos and an alto, given the three angel singers resemble children and children’s choirs are typically made up of these two particular voice types. By representing all these instruments and voices together, the painter evokes loud, rich and blissful music, evocative of some of the villancicos composed for the liturgical celebration of Christmas, and thus the birth of Christ, rather than the more staid and traditional plainchant. In its pure form, plainchant was sung in religious services without any instrumental accompaniment.1 However, plainchant was often performed not in this pure form, but rather accompanied by an organ—an instrument not included in this composition. Since the painting is not a realistic representation of a musical ensemble performing, it would be difficult to find a repertoire written exactly for the group of voices and instruments represented in the painting. Rather than corresponding to a specific piece of music, the presence of music within The Nativity with Musical Angels is itself theologically significant. Music provides a bridge to understanding the mystery of the nativity by showing the newborn Jesus as the one responsible for producing universal harmony.

The gaze of the infant Jesus provides the vital impulse to the angelic orchestra. The infant looks down to the side and the angel harpist who falls in the line of his gaze returns his glance. This angel is one of two whose eye movements are clearly depicted. This crossing of glances gives a deeper sense to the angelic orchestra; it materializes one of Thomas Aquinas’s discussions: whether God, as a spiritual substance, can move corporeal matter or not.2 The infant’s gaze then behaves like Aristotle’s immobile motor—that is, as the primary cause or “mover” of all the motion of the universe—by symbolizing an eternal incorruptible and immaterial substance, which exists as the ultimate cause of music.3 The baby Jesus does not seem to make any physical movement of his body, but his gaze nonetheless inspires the angels to perform. In The Nativity, the first instrument to be affected in this process is the harp, an instrument that would appropriately provide an essential harmonic foundation over which the vocal and instrumental music could then unfold.

The triangle introduces a vernacular touch into this Christian adaptation of the Greek theory known as the Harmony of the Spheres, a philosophical concept that regards the movements of the celestial bodies as a form of music. Unlike that of the angelic orchestra, this music is not audible to the human ear. Rather, it is a religious concept that might be intimately experienced, or even internally heard, as a sort of harmony. In this kind of religious musical scene, local painters often included angels playing the triangle with or without jingling rings attached to the horizontal bar.4 The triangle performer in The Nativity looks up at a cloud burst. Through the opening in the clouds, we can see a trio of angels singing what may be a different genre of music under the guidance of God the Father. The direct divine inspiration suggests that the music is religious and serious, traits that imply Latin liturgical polyphony rather than the more lively and festive villancicos. Devotees viewing the painting may have imagined that the three angels were singing something similar to the invitatory “Christus natus est nobis” (Christ is born to us) used for matins on Christmas Eve, or perhaps a motet inspired by Luke 2:14: “Gloria in altissimis Deo,” which is written on the phylactery held by two pairs of angels.

The composition does not depict a scene that is musically realistic. The simultaneous performance of both ensembles makes little sense, for their music would interfere with each other creating chaos rather than beauty. Their juxtaposition may, however, have a symbolic connotation. Each group represents the two main division of the church repertory: a vocal and instrumental ensemble for bright and joyful villancicos, and a smaller, subtler, vocal grouping for complex Latin polyphony (or maybe traditional plainchant) that formed the everyday fare of church choirs. Someone accustomed to praying in front of the painting might join the angelic choirs and orchestra by saying (or singing) out loud the text held on the angels’ phylactery: “Gloria in altissimis Deo.” The Novena para celebrar en compañía de todos los coros angélicos el Nacimiento del Niño Jesús (Novena to celebrate the birth of the Christ child in the company of all the angelic choirs) (Puebla, 1774) encouraged devotees to recite this phrase every hour while kneeling before an image of the Nativity.5 This action was to be repeated for nine consecutive days. A novena (from the Latin, novem, meaning nine) is a nine-day period of private prayer to obtain special graces. Devotees were supposed to prepare their souls to receive Jesus as their savior over that period. They were also expected to entrust themselves to the heavenly court and to join in the collective praise. Following these pious instructions allowed devotees to experience the cheerful joy of the angels musically announcing the birth of Christ.

- 1Pablo Nasarre, Escuela música según la práctica moderna (Zaragoza: Diego Larumbe, 1724), 91.

- 2Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae I. q. 105. a. 2. Emanuel Winternitz posits that this argument could also explain the mysterious Virgin and Child painted by Geertgen tot Sint Jans. See Winternitz, “On Angel Concerts in the 15th Century: A Critical Approach to Realism and Symbolism in Sacred Painting,” The Musical Quarterly 49, no. 4 (1963): 450-463.

- 3Aristotle, Metaphysics , XII. 6. 1071b4-5.

- 4Another triangle can be seen in the anonymous Death of Saint Joseph, which is also in the Collection of Carl & Marilynn Thoma.

- 5Novena devota para prevenirse a celebrar en compañía de todos los coros angélicos el Santísimo Nacimiento del Niño Jesús (Puebla: Herederos de la viuda de Miguel de Ortega, 1774), Centro de Estudios de Historia de México, 248.143.72.49 VA. It is probable that similar chapbooks circulated within the convents in viceregal Peru.

The Sleeping Christ Child was probably copied from a group of interrelated engravings. The engraver Hieronymus Wierix revisited the iconography of the Virgin Mary contemplating her son repeatedly. Multiple versions exist by Wierix showing the Virgin and Christ child alone in the composition (Fig. 6), while in other versions Wierix introduced the figure of Saint Joseph and an angel, and in yet another version the engraver added two additional angels in the corners. The flowery blanket covering the Christ child seen in all of Wierix’s variations on this iconography firmly link these prints to The Sleeping Christ Child. As Rosario Granados points out, the Weirix prints do not include all elements of the Thoma painting. For example, the known Weirix prints lack of the figure of the silent child John the Baptist.1 Nevertheless, they seem to have established an iconographic type that was then incorporated into the iconography of the Marian type known as Nuestra Señora de la Novena or Our Lady of the Novena.27 Nuestra Señora de la Novena was a mirarcle-working image largely venerated in Madrid beginning in the early-seventeenth century. A print of the iconography made by José Querol in 1798 is too late to have been the model for the Thoma painting, but preserves its iconography, showing the Virgin Mary in contemplation of the child Jesus with Saint Joseph and Saint John the Baptist with his finger to his mouth to either side (Fig. 7).2 The painter’s choice to represent the Virgin crowned and to include the flowery blanket suggest either a familiarity with both the Wierix prints and prints of Nuestra Señora de la Novena, or the possibility of an early engraving of Nuestra Señora de la Novena that incorporated more of the iconographic elements from the Weirix print.

Its possible print sources aside, The Sleeping Christ Child is a complex image marked by the confluence of multiple symbols. The resting body of the baby Jesus foreshadows his death. This iconography evolved as a result of the adaption of the Hellenistic tradition to humanistic Christian thought. Jesus as a child lying on a bed of flowers resembles Eros, the child-god of love, who was generally represented as a sleeping winged infant holding a bouquet of poppies.3 The infant John with his index finger under his lips mimics the gesture of Harpocrates, a child-god of secrecy and silence.4 In his Volgarizzamento delle Vite dei Santi Padri (Venice, before 1474), Domenico Cavalca suggests that silence symbolizes John’s knowledge of the Passion.5 His vigilant watch over the Christ child is meant to keep him sleeping; human redemption is supposed to occur in Jesus’s dreams. Saint Augustine similarly argued that sleep as a symbol of death recalled the promise of resurrection.6

- 1Rosario I. Granados “Research Update. September 2016-January, 2017. Collection of Carl & Marilynn Thoma,” unpublished text. According to Granados, Suzanne Stratton-Pruitt suggested Wierix might have produced an additional version of this iconography, now unknown, which included the John the Baptist figure. I am grateful to Granados for providing me with this information.

- 27Ibid.

- 2José Querol, Nuestra Señora de la Novena, Biblioteca Nacional de España, INVENT/14095.

- 3María Luisa Loza Azuaga and Daniel Botella Ortega, “Escultura romana de Eros dormido de Lucena (Córdoba),” Mainake 2, no. 32 (2010): 996.

- 4Philippe Matthey, “‘Chut!’ Le signe d’Harpocrate et l’invitation au silence,” in Dans le laboratoire de l’historien des religions. Mélanges offerts à Philippe Borgeaud, eds. F. Prescendi y Y. Volokhine (Genève: Labor et Fides, 2011), 542.

- 5Domenico Cavalca, Volgarizzamento delle Vite dei Santi Padri [before 1474] (Napoli: Raffaele de Stefano, 1836), 376-377. Domenico Calvalca’s work is the primary literary source for the iconography of John the Baptist. See Marilyn Aronberg Lavin, “Giovannino Battista: A Study in Renaissance Religious Symbolism,” The Art Bulletin 37, no. 2 (1995): 86-87.

- 6Augustine of Hippo, “Exposition on Psalm 127,” in Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers: First Series, ed. Philip Schaff and Kevin Knight, trans. T. E. Tweed (Buffalo, NY: Christian Literature Publishing Co, 1888), http://hdl.handle.net/10079/cde4fdd0-6446-4091-9b95-eb9e1103ca0d.

The Sleeping Christ Child

The experience of contemplation of The Sleeping Christ Child was full of ambiguity. Peaceful rest and hidden suffering were meant to be simultaneously present in the composition. Moreover, the infant Saint John the Baptist calling for silence might have made the pious beholder think of a song, perhaps a villancico, which would have reminded the viewer of the importance of silence. The Sleeping Christ Child in the Thoma Collection (Fig. 2) belongs to an iconographic type that represents the Holy Family with the child Jesus in his cradle. This type of representation was very popular in Latin America during the eighteenth century.

With his fingers, the sleeping child points to two small figures that stand before his bed. Their joined hands symbolize the union between Christ (the winged infant) and the human soul (the girl). This image is based on a third print, “Amor æternus,” an emblem included in Otto Vaenius’s Amoris Divini Emblemata (Antwerp, 1615) (fig. 8).1 The connection between Christ and the human soul is also expressed by the golden ribbon that ties them together and the inscriptions that span both the two hearts, human and divine. The first inscription, “Ego dormio et cor meum vigilat” (I sleep, but my heart waketh, Song of Songs 5:2), refers to the concept of waking sleep, a common theme in meditations on the sleeping Christ. The idea of waking sleep is pronounced in monastic mystical writings that draw on the books Songs of Songs and Job, especially those by Gregory the Great and Bernard of Clairvaux.2 According to these thinkers, sleep is a type of death; it removes the body from life’s cares, but at the same time, it keeps the soul awake attending to the encounter with God, just as in the parable of the wise and foolish bridesmaids (Matthew 25:1-13). Waking sleep suggests that body and soul are not divided in the effort to achieve the mystical union with Christ. In The Sleeping Christ Child this “waking sleep” is represented by the open eye in the sacred heart.

- 1Otto Vaenius, Amoris Divini Emblemata (Antuerpiæ: Ex officina Martini Nuti & Ioannis Meursi, 1615), 17.

- 2Gregory the Great, “Moralia Book V: 54,” in The Books of the Morals of Saint Gregory the Pope, or an Exposition on the Book of the Blessed Job (Oxford: J.H. Parker, 1844), http://hdl.handle.net/10079/197b3c6c-29b1-448e-82e4-2a4d7c2b2e8f; Bernard of Clairvaux, Sermon LII. 3-4. Life and Works of Saint Bernard Abbot of Clairvaux. Cantica Canticorum. Eighty-Six Sermons on the Songs of Solomon, vol. 4, ed. John Mabillon (London: Hodges: 1893), 315-316.

The second inscription, “Dilectus meus mihi, se ego illi, qui pascitur inter lilia” (My beloved is mine, and I am his: he feedeth among the lilies), quotes Song of Songs 2:16. Christian theologians interpreted Song of Songs as a dialogue between an aromatic bride (the soul) and a fragrant bridegroom (God) that attract each other, ultimately joining in a spiritual marriage on a symbolic bed of flowers.1 It is not a coincidence that a large garland of roses, lilies, and jasmines frames the scene. Flowers symbolize the array of Christian virtues (such as charity, faith, hope, obedience, perseverance, chastity, poverty, patience and humility). Religious texts often compare the achievements of women to garlands of fragrant flowers. For instance, in his 1733 eulogy to limeña beata (lay holy woman) Feliciana de San Ignacio Mariaca, José del Castillo Bolivar compared Mariaca’s virtues to amaranth, immortelle flower, caltha, hyacinth, rose, violet, and lily.2 Furthermore, nuns, in particular the Carmelites, tended to interpret the sweet smell of flowers as a reward from God for true devotion.3 Even if smell was usually ranked third in the hierarchy of the senses after sight and hearing, it still played an important role within religious frameworks as a way to confirm women’s virtuousness.4

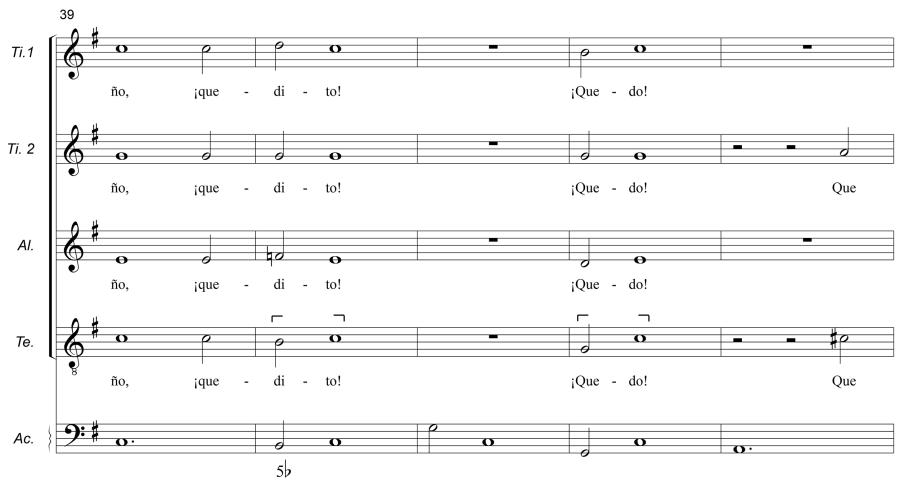

Lullaby villancicos confirm the affective content of the many symbols displayed in The Sleeping Christ Child. The theme of the lullaby villancico was typically lulling the Christ child to sleep, but also they also reminded the listener that the sleeping baby Jesus dreams of his future Passion. This topic received particular attention in colonial Chuquisaca (known today as Sucre, Bolivia) by means of musical pieces of a high level of complexity and originality.5 Si el Amor se quedare dormido (If Cupid Would Fall Asleep) exemplifies this type of lullaby villancico. The anonymous lyrics (first set in Madrid, in 1697) share important features with the iconography of The Sleeping Christ Child.6 Both the painting and the villancico highlight the opposition between sleep and waking, insisting on maintaining a balance between the two states (ex. 1).

- 1Classen, The Color of Angels, 55. Matthew Boersma, “Scent in Song: Exploring scented symbols in the Song of Songs," Conversations with the Biblical World 30 (2011): 80-94.

- 2José del Castillo Bolívar, Ramillete sagrado compuesto de flores que cultivó en heroicas virtudes la venerable sierva de Dios Feliciana de San Ignacio Mariaca, hija del orden tercero de penitencia de nuestro padre San Francisco (Lima: Imprenta de la Calle de Palacio, 1733), 6.

- 3José Gómez de la Parra, Fundación y primero siglo. Crónica del primer convento de Carmelitas descalzas en Puebla, 1604-1704 (México: Universidad Iberoamericana, 1992), 399.

- 4Classen, The Color of Angels, 59.

- 5Bernardo Illari, “Polychoral Culture: Cathedral Music in La Plata (Bolivia), 1680-1730,” vol. 1 (PhD diss., University of Chicago, 2001), 162-163.

- 6Villancicos que se han de cantar en la Real Capilla de su Majestad la noche de Reyes de este año de 1697, Biblioteca Nacional de España, VE/91/38(1).

Estribillo

Si el Amor se quedare dormido,

y herido de amores,

en catre de flores

quiere descansar,

¡Ay, ay, ay!,

¡Dejadle dormir!

¡Dejadle velar!

que de rey los desvelos

aun al sueño le roban el sueño.

¡Quedito, quedo,

que vela dormido,

que duerme despierto!

Nadie se mueva,

que de amor en la pena

duerme el sentido

y el alma vela.

Coplas

El Niño gigante,

dejando la guerra,

se viste de amante,

y dando en la tierra

su valor constante

vence con gemir

su misma dolencia

¡Dejadle dormir

y nadie se mueva!

Con su llanto ardiente

trae corazones

de todo el oriente,

sus blandos arpones

le hacen más doliente

de amor singular

que el pecho penetra.

¡Dejadle velar

y nadie se mueva!

El suspiro blando

de su mismo aliento

lo arrulla callando

y el grande contento

le está preparando

catre en que vivir

pueda su fineza.

¡Dejadle dormir

y nadie se mueva!

De rey poderoso

las grandes finezas

hacen cuidados,

del hombre tibiezas

turban el reposo

sin poder formar flores

en que duerma.

¡Dejadle velar

y nadie se mueva!

Estribillo

If Cupid would fall asleep

and, wounded by love,

on a bed of flowers

he would like to rest,

Oh, oh, oh!,

Let him sleep!

Let him wake!

For as King, his worries

steal sleep even from slumber.

Quiet, quiet,

for he wakes while sleeping,

and he sleeps while waking!

Nobody move,

for in the pangs of love

the senses are asleep

and the soul awakes.

Coplas

The giant child,

leaving war,

dresses up as lover,

so descending to earth,

his constant courage

defeats with moans

his own suffering.

Let him sleep

and nobody move!

[The child] with his ardent cry

draws hearts

from all over the Orient;

his tender harpoons

make him suffer

of a unique love,

which penetrates his chest.

Let him wake

and nobody move!

The soft sigh

of his very breath

lulls him in silence,

and the great joy [of his birth]

is preparing him

a cot in which

his kind presence can live.

Let him sleep

and nobody move!

The great kindnesses

of a powerful King

cares for the people;

man’s tepidity

disturbs his rest [of the King]

without growing flowers

on which he can sleep.

Let him wake

and nobody move!

Juan de Araujo, choirmaster of the cathedrals of Lima and Chuquisaca in the late-seventeenth century, set the poem to four-part music. His setting survives in manuscript part books copied towards 1713 that may have belonged to the Franciscan convent of Santa Clara.1 Araujo’s villancico was presumably sung there at least once in 1754, as indicated on the front page. Si el Amor se quedare dormido presents the villancico’s customary division in two sections: a through-composed estribillo (that is, an opening section that does not have any internal repeats) and a set of four strophic coplas. The fancy estribillo operates as a rhetorical exordium, catching the listener’s attention. The coplas present the religious core of the piece, as if it were a song-within-a-song.2

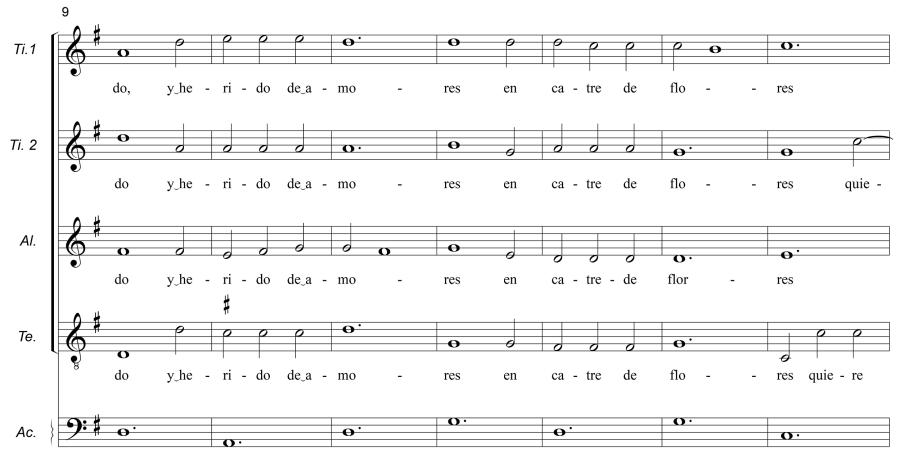

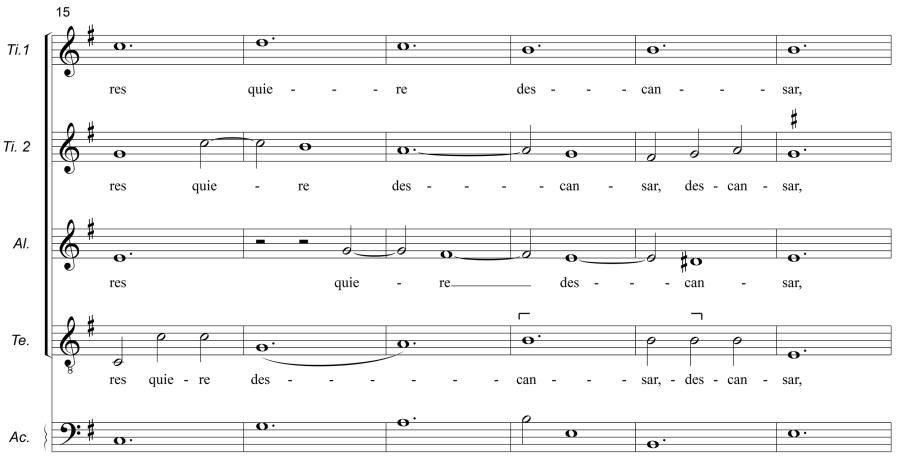

Araujo’s setting communicates the emotional content of the poem using musical language that enhances the feeling of unrest and suffering.3 An abundance of changes in tonal focus supports this musical idea, breaking and playing with the expected sense of tonal unity. Important concentrations of successive dissonances appear in the passage, which describes the Christ child “wounded by love,” (“herido de amores”) embodying Jesus’s suffering (ex. 2, m. 9-15). By contrast, the music evokes restful sleep, “he would like to rest” (“quiere descansar”), through lengthy notes and ligatures in slow, flowing melodies (ex. 3, m. 15-20).4 The soft and languid character of this passage matches the affection of the words considered to be appropriate to provoke drowsiness, but also to instill sadness. The expressive interjection “¡Ay!” (Oh!) (ex. 4, m. 21-23) reinforces the painful affection of the piece by interrupting the continuity of the composition.

- 1Archivo y Bibliotecas Nacionales de Bolivia, Juan de Araujo, Si el Amor se quedare dormido , Música 156.

- 2Illari, “Polychoral Culture,” 168.

- 3For a recorded version of the piece: Juan de Araujo, Si el Amor se quedare dormido, Ensemble Elyma, Gabriel Garrido, Nuevo Mundo 17th-Century Music in Latin America, Glossa 4, 2017, CD, http://hdl.handle.net/10079/f1d828a2-9d4a-4aa1-a322-c3fba55cc609.

- 4Bernardo Illari, “Agudeza de villancico: los Plumajes de Torrejón,” in El villancico en la encrucijada: nuevas perspectivas en torno a un género literario-musical (siglos XV-XIX) , eds. Esther Borrego Gutiérrez and Javier Marín López (Kassel: Reichenberger, 2019), 504-505.

Example 2. Si el Amor se quedare dormido, m. 9-15.

Example 3. Si el Amor se quedare dormido, m. 15-20.

Example 4. Si el Amor se quedare dormido, m. 39-43.

Silence in relation to music does not exist as a vacuum. The poem brings up the conventional order “¡Quedito, quedo!” to quiet the audience and let the child sleep. The four voices remain silent, but not the basso continuo (a harmonic support and rhythmic accompaniment typically realized with a harp) (m. 39-43). Silence is eloquent; it does not merely articulate sound structures. The paradox of music evoking silence could be understood as a means to encourage the audience—as the infant Saint John the Baptist does in the painting—to perceive in the slumber of Jesus, even for a brief moment, its importance for redemption.

A set of four strophic coplas comes after the estribillo. The repetitive simplicity of their music and their careful rhythmical setting are an apt vehicle for conveying the poem’s contents. The first three coplas associate the Christ child’s tears, moans, and sighs with Cupid’s weapons on the basis of their capacity to move the devotee (who might be the listener or the beholder). The fourth copla charges human indifference as being responsible for not cultivating flowers or virtues. Human indifference and the resulting absent flowers and virtues may interrupt Jesus’s sleep and prevent human salvation. Si el Amor se quedare dormido captures the ambiguity of The Sleeping Christ Child. It bridges the disjunction between wakening and sleep, inviting the devotee to contemplate the peaceful, but also suffering baby Jesus.

The emotional states implied in The Sleeping Christ Child and The Nativity reflect the alternation between tears and bliss that early modern Catholics saw in the childhood of Christ. Since the sixteenth century, one of the concerns of preachers and spiritual directors—both in Europe and the New World—was to teach the faithful to experience “spiritual delight,” while reflecting on the many episodes of the infancy of Christ. That emotion was supposed to be a mixture of suffering and joy.1 The paintings analyzed so far exemplify this form of emotional training. They stay within conventions, but exploited the manifold relations among sight, hearing, and smell to intensify the devotee’s religious commitment.

- 1See, for instance, Fray Luis de Granada, Sermones de tiempo , vol. 1 (Madrid: Plácido Barco López, 1790), 381-382.

Conclusion

A rich sonority pervades The Nativity and The Sleeping Christ Child. It is us, the contemporary beholders, who think of colonial religious images as silent, exclusively focused on the eye. This means that we have lost the capacity to perceive the connections suggested in devotional paintings among different senses. Those links were employed as a means for enhancing the faithful’s spiritual perception; their aim was to provide a deeper insight into theological concepts, helping devotees to develop a way of looking and listening that would foster direct contact with the supernatural.

In past work on devotional images of the Christ child and villancicos, I have demonstrated that the early modern Catholic symbolic sphere characterized music as an essential feature of female nature.1 In the early modern Spanish world, women’s souls were metaphorically conceived as musical instruments. In theory, there were diverse paths to tune those unusual instruments. One of these paths was to actively practice the Christian virtues by thinking about them as if they were the chords of the human soul.2 Another approach was to reflect on the content of images that evoked the perfect harmony of Christ, who was supposedly a musical instrument himself. In that case, the tuning of the feminine soul would occur by means of a mystical sympathetic resonance.3 The Nativity and The Sleeping Christ Child might be included in this genre of musical images since both were intended to offer a path to reach spiritual perfection primarily through the sense of hearing.

Visual representation of music (or at least of topics that might be related to music, such as the waking sleep) points to the beholder’s capacity to internalize the aural experience, mentally linking music or silence to theological concepts and emotions. Otherwise, the depictions of either of those features would be meaningless. This process of association acted within the boundaries of a complex system of symbols that shaped the sensibility and behavior of the faithful.4 In The Nativity and The Sleeping Christ Child, symbols serve as a portal into a world centered around listening. They allow us to understand how women were supposed to feel and live their devotional experiences.5 Even though they were painted separately, both artworks sound together in a sort of consonant harmony. We must identify and interpret the range of symbolic elements these works carry, so that we can attune ourselves to the resonance they share. In order to do so we must learn to hear visuality in Spanish colonial art.

- 1“Carolina Sacristán Ramírez, “El entramado de la devoción: pintura, música, religiosidad femenina y el Niño Jesús Pasionario en la Nueva España, 1720-1772” (PhD diss., Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2018). See Chapter 2: “El Niño Jesús tañendo la cruz, c. 1730-1740.” On this subject, see also Ronald E. Surtz, The Guitar of God: Gender, Power and Authority in the Visionary World of Mother Juana de la Cruz (1481-1534) (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990), 63-85. Ronald E. Surtz, “Imágenes musicales en el libro de la oración (¿1518?) de sor María de Santo Domingo,” Actas del IX Congreso de la Asociación Internacional de Hispanistas 18-23 agosto 1986, Berlín (Vervuert: Frankfurt am Main, 1989), 563-570.

- 2Carolina Sacristán Ramírez, “Cantando ‘La huida a Egipto’ con la cítara mística: meditación y música en un devocionario novohispano del siglo XVIII,” Cuadernos del Seminario de Música en la Nueva España y el México Independiente 10, in press.

- 3Sacristán Ramírez, “El entramado de la devoción,” 42-83. Sympathetic resonance is a harmonic phenomenon wherein a passive string responds to external vibrations to which it has harmonic likeness.

- 4This idea is based on Clifford Geertz’s definition of religion: “Religion as a Cultural System," in The Interpretation of Cultures: Selected Essays (London: Fontana Press, 1993), 87-125.

- 5As Geertz suggests, “The world as lived and the world as imagined, fused under the agency of a single set of symbolic forms, turn to be the same world,” The Interpretation of Cultures (New York: Basic Books, 1973), 112.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2019.1

1. Carolina Sacristán-Ramírez, "Audible Paintings: Religious Music and Devotion to the Infancy of Christ in the Art of the Viceroyalty of Peru," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 1 (2019), doi:10.22332/mav.ess.2019.1

Sacristán-Ramírez, Carolina. "Audible Paintings: Religious Music and Devotion to the Infancy of Christ in the Art of the Viceroyalty of Peru." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 1 (2019). doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2019.1