Alessandra Amin is a PhD candidate in the Department of Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her dissertation considers the twinned emergence of fantastical imagery and a symbolic language of familial coherence in Palestinian art during the heyday of the PLO, asking how these visual vocabularies shaped the anticipatory, aspirational space of a future Palestinian state. Her research has been supported by the US Department of Education, the Social Science Research Council, Darat al-Funun Center for the Arts, and the Palestinian American Research Center.

Most routes through Mount Lebanon are winding and narrow, lined by oak, cedar, and cypress trees and roamed by the occasional sheep. The road to Our Lady of Diman is no exception and the church’s spacious parking lot seems to emerge out of nowhere. The stately edifice overlooks the Qadisha Valley, known for both its natural beauty and its religious significance to Lebanese Christians, especially Maronite Catholics. The imposing architecture and impressive location of the church befit its purpose. Since its construction around the turn of the twentieth century, it has served as the summer residence of the Maronite Catholic Patriarch.1 The prestige of the building is everywhere apparent: in the inlaid marble floor, in the gold and blue panes of the stained-glass windows. The church’s most remarkable feature, however, is the ceiling over its nave, with frescoes completed in the late 1930s by celebrated Lebanese painter Saliba Douaihy (1913-1994).

- 1According to the Maronite Foundation, construction of the Patriarchate in Diman began on September 28, 1899. https://maronitefoundation.org/MaroniteFoundation/en/MaronitesHistory/57

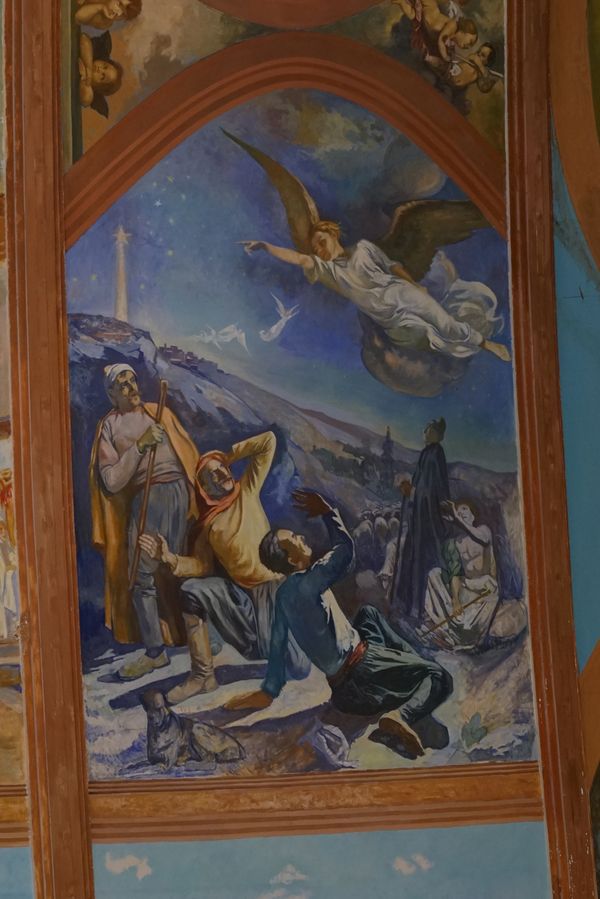

The frescoes depict twelve episodes from the life of Christ, surrounded on three sides by a panoramic landscape of the Qadisha Valley. These scenes are divided by wooden molding (actual and trompe-l’oeil) and arranged in three horizontal registers, flanked on either end by a single painting. Above the western gallery, Christ walks on water, offering his hand to a struggling sailor. Moving towards the apse, the first register of multiple paintings offers three Marian scenes: the Immaculate Conception of Mary, the Coronation of the Virgin, and the Annunciation. The next juxtaposes the Transfiguration of Jesus with the Annunciation to the Shepherds, drawing parallels between Christ’s birth and his miraculous appearance to his disciples. Following this, the Crucifixion and the Nativity frame the story of Jesus and the Woman Caught in Adultery, emphasizing Christ’s mercy as a figure who was born and died to cleanse the world of its sins. Furthering this theme, the penultimate paintings pair a depiction of Christ’s baptism by John the Baptist with the miracle of the Resurrection. Finally, closest to the altar, a depiction of Christ’s ascension to Heaven provides a triumphant conclusion to the ceiling’s narratives.

At first glance, the paintings may seem unremarkable. Their biblical subjects are not unusual, their style seemingly derivative of an outmoded, almost gaudy strain of Western academic painting. A closer look, however, sheds light on the complexity of the frescoes as a product of their fraught times: completed during the run-up to Lebanese independence, they offer insight into the nexus of imperialism, sectarianism, and cosmopolitanism in which Lebanese nationalism blossomed. In line with a Christian nationalist conception of the budding republic, Douaihy’s Lebanon is defined by both its alignment with Western Europe and its distinction from the rest of Greater Syria, anchored in Mount Lebanon—the mythologized geographical center of Lebanese Christianity.1 The ways in which this perspective manifests in the Diman frescoes become apparent only in conversation with the artist’s personal history, as well as this history’s place in the annals of modern Lebanese art.

- 1In this context, “Greater Syria” refers generally to the historic region of the Levant (comprising modern-day Syria, Palestine, Jordan, and Lebanon) and, more specifically, to the French Mandate for Syria and the Levant (1923-1946), established during the European partition of the Ottoman Empire following World War I.

Saliba Douaihy was born into a Maronite Catholic family in the town of Ehden, about eighteen kilometers from Diman in the district of Mount Lebanon. From its inception, his artistic education was managed by the Maronite Patriarchate, which sent a teenage Douaihy to study at the Beirut atelier of prominent painter Habib Srour (1860-1938).1 Srour, who had trained in Italy, taught the budding artist for several years before recommending that he, too, complete his education abroad. In 1932, Douaihy left to study in Paris under the auspices of a fellowship from the Franco-Lebanese government, returning to Lebanon four years later when Maronite Patriarch Antoine ‘Arida commissioned the frescoes at Our Lady of Diman.

- 1Badr El Hage, collected interviews with Saliba Douaihy. Published in the Mathaf Encyclopedia of Art and the Arab World: http://www.encyclopedia.mathaf.org.qa/en/essays/Pages/Saliba-Douaihy,-Autobiography-and-Artistic-Views.aspx

Douaihy’s academic trajectory was a typical one, inherited from the first generation of modern Lebanese easel painters. For these “pioneers,” including Srour and his mentor, Daoud Corm (1852-1930), and their immediate successors, training was generally conservative and success was often predicated on European education. There was no formal institution of arts education in Lebanon until 1943, and government scholarships for study abroad were usually the best means for aspiring artists to hone their skills. Like most institutions under the French Mandate, this ad hoc system overwhelmingly favored Christians, who occupied a privileged position vis à vis the colonial government. The Maronite Catholic community in particular produced a disproportionate number of artists, having nurtured cultural ties to Europe long before the advent of the French. Though instruction in the visual arts was available at military academies during the later decades of the Ottoman Empire, the tradition of easel painting in Lebanon is most closely tied to the Catholic church, purportedly originating with the establishment of the Maronite College of Rome in Mount Lebanon in 1584.1 A history of Lebanese cleric-painters can be traced back to the 1600s, and in the 1830s the Vatican itself sponsored the development of oil painting among Jesuits in Lebanon as part of a larger campaign to shore up the Maronites’ place among Uniate churches and foster its “historical ties” to the West.2

- 1Matthew Burrows, “‘Mission Civilisatrice’: French Cultural Policy in the Middle East, 1860-1914,” The Historical Journal 29, no. 1 (March 1986): 112.

- 2Stephen Sheehi, “Modernism, Anxiety, and the Ideology of Arab Vision,” Discourse 28, no. 1 (Winter 2006): 77. For more on the early history of oil painting in Lebanon, see Sarah Rogers, “Daoud Corm, Cosmopolitan Nationalism, and the Origins of Lebanese Modern Art,” The Arab Studies Journal 18, no 1. (Spring 2010): 46-77; Silvia Naef, A la recherche d’une modernité arabe: l’évolution des arts plastiques en Egypte, au Liban et en Irak (Geneva: Slatkine, 1996); Charbel Dagher, “How Painting Came East,” translated by Pauline Homsi Vinson, al-Jadid: A Review of Arab Culture and Arts (Summer/Fall 2006): 11-15.

The longstanding relationship between the Maronite Patriarchate and Western Europe is exemplary of a broader cultural politics that came to a head during Douaihy’s lifetime. Intellectuals throughout the Arab world had debated the ideal balance of “Western progressivism” and “Eastern tradition” since the nahda, or renaissance, of the late-nineteenth century, but, as Sarah Rogers has noted, in Lebanon’s case this balance became a point of pride rather than anxiety in its march towards independence.1 Christian intellectuals embraced Western influence as the basis of Lebanon’s “paradoxical cosmopolitan nationalism,” linking Maronite connections to Italy and France to Beirut’s long history as a mercantile crossroads. Furthermore, they downplayed the “Arabness” of Lebanese culture by stressing the country’s roots in Phoenician society. This narrative of Lebanon’s history largely bypassed its rich Islamic heritage and subsequently fueled the country’s growing sectarian divide. Inextricable from the region’s history of colonialism, Lebanese sectarianism is far from a clear-cut phenomenon, but certain general trends of religious and social identification intensified during French rule with implications for the visual arts.2 Broadly speaking, Christians built on a politically expedient cultural affinity with Europe while Muslims, increasingly disenfranchised following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, extolled the virtues of Arabism and were quicker to condemn European imperialism in the region. Unsurprisingly, Christian artists were not only likelier candidates for state-sponsored support, but were also more receptive to Western modes of education, production, and representation.3

Saliba Douaihy’s Diman frescoes offer a stylistic window into this history. After four years in Western Europe, the young artist “was glad to be painting in the style of Michelangelo and Raphael” when he embarked on the project, sequestering himself “like a hermit” for three weeks as he painted directly onto the plaster from a wooden scaffolding.4 Per his own description, the artist sought to combine elements of “classical and rococo styles” in these paintings, reflecting his training in the conservative, academicist traditions of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts under Srour and in Paris.10 Though the popularity of academic painting had waned in France by the time Douaihy arrived, the artist paid little attention to the contemporary art flourishing around him during his tenure there. “I used to visit art exhibitions with some of my colleagues,” he acknowledged, “but our passion was purely for the classical style, and everything outside of it was, in our view, a waste of time.”5 This, too, reflects the historical moment; as Stephen Sheehi has noted, the antipathy towards academic painting that spread throughout Europe in the first decades of the twentieth century went largely ignored by the intelligentsia of the Arab world.6 Instead, Arab artists and their limited publics demonstrated a widespread penchant for realism, rooted, as Sheehi argues, in the nahda’s project of positivist reform and encouraged by Maronite patronage.13

- 1See Rogers, “Daoud Corm.”

- 2See Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism: Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Ottoman Lebanon (Berkeley, Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996).

- 3The relative distance of Muslim artists from the European artworlds to which their Christian peers had access should not be mistaken for a religious aversion, as the oft-cited Qur’anic prohibition on figurative imagery had largely ceased to be relevant by the end of the nineteenth century. Lebanese Muslims filled the painting classes offered by the Ottoman military, and elite families often commissioned portraits by Christian and Muslim artists alike.

- 4Quoted by El Hage (online).; Father Jean Sader, “Saliba ad-Douaihy yurasm kinisa ad-Diman,” The Art of Saliba Douaihy, edited by Abbot Antoine Daou (Beirut: Fine Arts Publishing, 2015), 28.

- 10Ibid.

- 5Quoted by El Hage (online).

- 6Sheehi, “Modernism, Anxiety,” 77-78.

- 13Ibid.

Though artists including Douaihy, Srour, and Corm had access to contemporary European aesthetic currents, they all sought to “paint like Michelangelo or Raphael” rather than Monet or Picasso. Given the widespread aesthetic preference for realism and the increasingly strident association of Maronite Catholics with Italy and France, it is unsurprising that Douaihy’s paintings would purposefully evoke the Western European canon of late Renaissance and Baroque religious paintings. The frescoes’ brilliant colors and dramatic use of light evoke the work of Mannerist painters Pontormo (1494-1557) and El Greco (1541-1614), and his depiction of Mary’s immaculate conception features a composition and color palette strikingly similar to Spanish Baroque painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1618-1682)’s The Immaculate Conception of Los Venerables (1678). The frescoes even insert the two famous putti of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna (1513) into a gap between scenes.

In their allusion to canonical images and stylistic norms of European Renaissance art, these paintings do more than cater to the tastes of the Christian bourgeoisie. They also imbricate the highly valued cultural “treasures” of European history and the Maronite community of Mount Lebanon, playing into a well-established sectarian vision of the nascent Lebanese nation. Amidst these nods to Western “masters,” however, the figures in each episode are modeled after members of the local community. For example, the children of a prominent deacon appear as the Virgin Mary and the angel Gabriel in the Annunciation scene.1 Douaihy’s use of local models implicates Lebanese Christians as claimants to the artistic heritage of the European Renaissance, legitimizing the ties between Lebanon and Europe that Christian nationalists sought to maintain through the establishment of the new republic.

This interpretation is supported by the panoramic landscape bordering the twelve narrative paintings; the Qadisha Valley’s rocky, verdant terrain frames Christ’s life. In dialog with Douaihy’s choice of models, the landscape localizes the biblical stories, anchoring them to the immediate vicinity of Our Lady of Diman. Moreover, the sweeping panorama enshrines a landscape of both religious and political significance. Now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Qadisha Valley is home to the Forest of the Cedars of God as well as a proliferation of monasteries and hermitages.2 Its inhospitable cliffs have sheltered Christian ascetics for over a thousand years, and the some believe the valley itself to possess miraculous qualities. As the seat of the Maronite Catholic Church, the Qadisha Valley is also central to the image of “the mountains” (Mount Lebanon) that dominated nationalist debates during the 1930s. The accounts of French and Lebanese Christian historians in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries mythologized the mountains as a historic refuge for the oppressed, where religious minorities had thrived for centuries beyond the reach of the (purportedly tyrannical) Sunni ruling class.3 Though Shi’a and Druze communities are counted among these religious minorities, this history—the factual accuracy of which is subject to debate—largely served the interests of the Maronite Catholics to whom the French allocated political primacy.4 Mount Lebanon dominated French and Christian nationalist definitions of Lebanese cultural identity, positioning the nascent country as a “haven” of Westward-facing Christianity in a hostile Muslim region. The mountains were also central to the national borders for which these parties advocated. While their Arabist detractors sought to maintain a union with Syria, Christian nationalists envisioned a territorially discrete entity anchored in Mount Lebanon.

- 1Sader, “Saliba ad-Douaihy,” 28.

- 2The Forest of the Cedars of God is what remains of a once-vast cedar forest that provided valuable timber for civilizations from the Phoenicians to the Ottomans and is mentioned in both the Bible and the Epic of Gilgamesh.

- 3The mythology surrounding Mount Lebanon, though mobilized through the twentieth century, is most intimately tied to the Mount Lebanon civil war of 1860. The sectarian tensions that gave rise to the conflict were exploited and exacerbated by foreign powers; the primary antagonists, Maronite Christians and Druze, were supported by the French and the British, respectively.

- 4See Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism, Ch. 5; Kamal S. Salibi, A House of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered, (London: IB Taurus & Co., 1988), 130-150; Kais Firro, Inventing Lebanon: Nationalism and the State under the Mandate (London: IB Taurus, 2002); Fawwaz Trablousi, A History of Modern Lebanon (London; Ann Arbor: Pluto Press, 2007).

Douaihy thus completed his commission at a time when Mount Lebanon held enormous symbolic capital. Although the artist may not have painted the Qadisha Valley in a consciously politicized way, during the first decades of the twentieth century Lebanon’s Maronite community increasingly supported independence from France, and considered the mountains the epicenter of a discrete Lebanese nation. The envisioned nation was itself characterized by a cultural affinity with the West. Douaihy’s Biblical scenes, aesthetically indebted to the European canon and populated by the church’s community, speak to the place of this international bond in his social milieu. Douaihy’s frescoes shed light on the cultural valences of contemporaneous sectarianism, on the inextricable nature of religious and secular spheres as they intersected over Mount Lebanon in the 1930s. The Church of Our Lady of Diman gains gravitas from the connections it makes across the Mediterranean, but it also points to the fissures that widened closer to home.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.obj.2020.3

1. Alessanda Amin, "Mural Paintings, Church of the Summer Residence of the Maronite Patriarch, Diman," Object Narrative, MAVCOR Journal 4, no. 1 (2020), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2020.3.

Amin, Alessandra. "Mural Paintings, Church of the Summer Residence of the Maronite Patriarch, Diman," Object Narrative. MAVCOR Journal 4, no. 1 (2020), doi: 10.22332/mav.obj.2020.3.