Traveling with Alvaro

I spent the summer of 2015 with a The Tucson Samaritans, a faith-based nonprofit organization that provides water, food, and medical supplies to border crossers.1 For me, this trip was both personal and political; as a former undocumented migrant, the narratives and experiences of border crossers remind me of my own. Hoping to gain a better understanding of religion’s role in migrant’s journeys, I imagined the majority of my time would be spent listening to and learning from border crossers themselves. Yet, as quickly as my first day on the job, the focus of my project shifted.

On July 6, while traveling from Tucson to the border with Mary and Bob—Samaritans volunteers—I noticed a cross on the side of the road. Imagining the cross was a roadside memorial—perhaps for the victim of a car accident—I did not understand why Bob suggested we pull over to see it. He explained that a fellow Samaritan, Alvaro Enciso, made this cross to honor a baby who died in her mother’s arms while on their journey to el Norte (the North).2 Mary told me this cross is part of a project by Alvaro in partnership with The Samaritans. He designs, creates, and plants crosses at the sites migrants died on their way to the United States.

As we drove away, I could not forget the cross or the rosary and small toys left as offerings for the baby. In my field journal, I noted the sight of the cross was “destabilizing. If I was someone else, I might be able to desensitize myself from these images but I can’t do that. It’s too much of a possibility that I could have been that mother or dead child.” Alvaro’s cross triggered something within me that I had long before buried; it drew me back to a time and a place I would rather forget.

A few days later, I accompanied Alvaro and his team on one of their weekly trips to the desert. We met at 7 a.m. at Southside Presbyterian Church, the gathering place for The Samaritans. Shortly after taking off, we stopped at McDonalds as Alvaro enjoys “shitty breakfast.” Cold air blasted from the vent above our table as we ate our sausage biscuits and discussed one of Alvaro’s favorite bands, Los Tigres del Norte. He emphasized the following lyrics from the norteño band’s song, “Somos Mas Americanos”—“We didn’t cross the border; the border crossed us”—giving me a small glimpse into his worldview.3

In drawing attention to these lyrics, Alvaro questioned the legitimacy of national borders while stirring up transnational longings for the mythical homeland Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa calls Aztlán. She too yearns for the time before “the border crossed us,” claiming, “this land was Mexican once, was Indian always and is. And will be again.”4 Such a longing for a time and a place before the colonizer arrived is the product of a borderlands people in-between and on the move. As Luis D. León argues, border crossings trigger mythical memory. Movements across borders “shift and rearticulate [a crosser’s] vision of place, body, and temporality,” unfolding a long mythical/historical memory tied to conquest, death, violence, and the redrawing of national boundaries.5 If the land “was Mexican once and Indian always,” migrants are not outsiders or “illegals.” They—we—belong to the land.

After breakfast, Michael, one of the volunteers, stopped at a grocery store to purchase bug spray for the team. As we continued on our way, we breezed through two border security checkpoints. Alvaro told me this was because border patrolmen recognize the red Samaritans truck.

Our pit stop did not seem that important to me at the time; in fact, I only made a passing reference to it in my field journal. Looking back, I realize just how significant that stop was. Our freedom to enjoy a “shitty breakfast” at an air-conditioned McDonalds and purchase bug spray at Safeway reveals much about our position within the border regime’s hierarchy of bodies and belonging.6 When Michael forgot his bug spray, he easily obtained some. He could move openly in daylight without fear, quite unlike migrants who are more often than not unprepared for their journeys. Our ability to eat, to access the necessities for our comparatively quick journey, and to move unimpeded through security stands out against the experiences of migrants who hide and move in the dark, who run out of water and do not even think to bring bug spray.

The team travels with a GPS linked to the Humane Borders databases.7 The GPS includes not only the exact coordinates of where the migrant’s body was found, but also key information about the person—their name, age, as well as the year and cause of death. The Medical Examiner’s office is tasked with finding this information.8

Upon reaching each destination, we loaded our backpacks with a gallon of water each—more if we were willing to carry it—as well as the cross, a shovel, and bucket of cement.9 With the midday sun beating down on our backs, we dug the requisite hole and drove each cross into the ground. Halfway through our day, we crouched underneath trees to get some shelter, sharing snacks with one another. In that moment, I imagined we could have been a group of migrants resting from our journey. Yet, despite all of our efforts to commune with the ghosts, we were different from them in every way.

As we ate, Alvaro retrieved a can of red spray paint from his backpack, painting a large dot on a metal water tank. This is the next phase in his project: putting large red dots on unexpected, everyday places. Alvaro paused for a moment to reflect on the marks he had made and how proud he was of “taking graffiti out of the urban and into the borderlands. Art in the middle of nowhere. Art where it doesn’t belong.”10 In this way, Alvaro links his art to the migrants who likewise are bodies out of place, people who lost their lives in the middle of nowhere, who don’t belong here or there, who belong nowhere.

From this spot we were less than .15 miles from the U.S.-Mexico Wall. From a distance, the wall seemed transparent, almost as if it were imaginary. Yet, after a summer spent with the ghosts of lost migrants, I know this wall is very real.

In using art to demand recognition for people who die alone and anonymous, Alvaro’s is a memory reclamation project. Marking these sites challenges the dominant progressive narrative about American democracy and citizenship, which purposefully leaves these sites unmarked because, as Michel-Rolph Trouillot argues, silencing is a powerful tool of national myth making.11 In making these lives sensible and perceptible, Alvaro’s work is a direct challenge to U.S. border policy, which seeks to exclude and erase certain bodies.

The U.S. government wishes to obscure migrant deaths because the exposure of these, “othered, foreign bodies,” to use Emily S. Rosenberg and Shannon Fitzpatrick’s language, would present a direct challenge to their border policies, revealing the human loss these policies cause. In their discussion of the U.S. media’s erasure of Hiroshima and Nagasaki’s victims to preserve a positive image of atomic bomb building and testing programs, Rosenberg and Fitzpatrick argue, “being absent from view—being erased—is the most profound kind of bodily marking. Bodies rendered invisible by the security state and within mass media cannot easily command attention. This process of erasure ‘silences the past’ and distorts history and public memory.”12 Keeping with Rosenberg and Fitzpatrick’s notion of the “disappeared body,” Alvaro’s artwork bears witness to the death that occurs in the border region and in doing so, brings these bodies into reality again beyond their actual material lives.

Border Militarization and the Dehumanization of Migrant Bodies

As I witnessed this summer, the two-thousand-mile long border between the United States and Mexico is marked by intense military technology including motion sensors, stadium lighting, and security towers, turning the border region into a literal war zone. The increase in military technology along the border can be traced to 1994, the year the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was implemented and border policy shifted to promote “prevention through deterrence.”13

NAFTA displaced hundreds of thousands of small farmers in Mexico who could no longer make a living as they had done before, leading to increased Mexican migration to the United States.14 While facilitating the free flow of goods and commodities, NAFTA also led to the increased regulation of unwanted, or “illegal,” brown bodies. A resurgence of nationalism and nativism in the U.S. after 9/11 further contributed to anti-migrant sentiment and policies that shored up U.S. borders and dehumanized border crossers. In 1994 there were approximately four thousand officers and a few miles of heavy fencing along the U.S.-Mexico border; by 2009, this number escalated to twenty-one thousand officers and 650 miles of fence wall.15

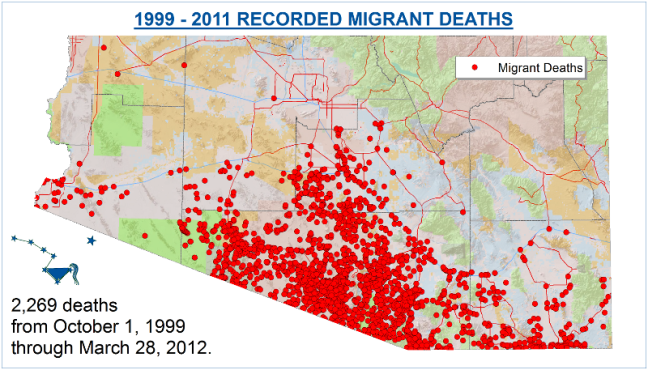

Prevention through deterrence led to increased technology and surveillance on urban corridors, which have pushed migrants to cross at more dangerous areas such as deserts and mountains.16 As a result, deaths along the border increased dramatically. Humane Borders has mapped 2,269 migrant deaths in southern Arizona between 1999 and 2012.17 More have been documented since then, including 141 in the last year.18 According to the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, the leading cause of death is exposure.19 Especially during summer months, border crossers can run out of water and be forced to drink their own urine to stay alive.20 Many die of exposure to heat, cold, dehydration, infection, motor vehicle accidents, heart attacks, or complications of diabetes.21

As Joseph Nevins argues, hyper-militarized territorial boundaries define nationhood and citizenship by limiting and excluding, that is, by distinguishing between “us” and “them.”22 He writes, “these boundaries . . . are an outgrowth, and simultaneously, a producer of nationalism, state power, and the ability of the state and the nation to shape our collective consciousness and, thus, practices.”23 The U.S. government shapes it’s citizens’ “consciousness and . . . practices” by labeling migrant bodies “illegal,” by deeming those bodies threats to the body politic, by imagining migrants as trespassers, invaders, and intruders. Feminist theorist Sarah Ahmed likewise discusses how these “others” are constructed in her influential text, The Cultural Politics of Emotion. She writes,

The 'illegal immigrants' . . . are those who are 'not us', and who in not being us, endanger what is ours. Such others threaten to take away from what 'you' have, as the legitimate subject of the nation, as the one who is the true recipient of national benefits. The narrative invites the reader to adopt the 'you' through working on emotions: becoming this 'you' would mean developing a certain rage against these illegitimate others, who are represented as 'swarms' in the nation. Indeed, to feel love for the nation, whereby love is an investment that should be returned (you are 'the taxpayer'), is also to feel injured [emphasis added] by these others, who are 'taking' what is yours.24

Themes of injury and woundedness are at play in Ahmed’s text and in the border region as a whole. Legacies of colonization, the border crossing “us,” and mass death and violence injure not only individual people and communities but also the land itself. To borrow from Anzaldúa again, the U.S.-Mexico border is “una herida abierta (an open wound) where the Third World grates against the first and bleeds.”25 The land is a permanent scar, the result of violent historical encounter(s). The border is wounded and it wounds.

Ahmed argues that cultural politics of emotions produce “others”—whether racial, gendered, or sexual—by including some bodies in the imagined community and excluding others. By fueling its citizens’ fear and rage, the nation-state contributes to the otherness of those born on the wrong side of the border. Alvaro’s project does just the opposite. His artwork draws on the power of emotions to mourn the migrants the U.S. border regime seeks to exclude and erase.

Bringing Attention to "Secret Casualties"

Alvaro first saw the red dots on the map above at a Samaritans training meeting in 2012. At first, Alvaro wanted to visit those sites and be physically present where someone had died looking for “a piece of the American dream.”26 He wanted to feel whatever emotions came to him in that moment.27 The importance of affect to this project cannot be overstated. Feelings—the artist’s, the volunteers, and the deceased’s—are central to the making and planting of the crosses. As Ahmed argues, “feelings are, in some sense, material; like objects, feelings do things, and they affect what they come into contact with.”28 Feelings are both the response to and the motivation for Alvaro’s project.

When he began investigating the Humane Borders databases, the first thing that caught Alvaro’s eye was the age of the dead—mostly men and women in their 20s and 30s. “They are too young to be dying; there is something terribly wrong happening here,” Alvaro shared with me. “I knew then that I needed to do something to bring attention to these secret casualties.”29

At first, Alvaro wanted to commission someone to manufacture red steel circles, about 20 inches in diameter, to use as markers for the sites. Yet, because of the cost and the difficulty of transporting the heavy circles, he abandoned this idea. Later, Alvaro tried spray painting red circles on the ground but was unsatisfied with the results. There were other ideas he discarded before deciding on the crosses.

In one of our email conversations, Alvaro wrote that, while a cross is a Christian symbol, he wants his crosses to be “more than that.” Alvaro wrote to me,

Crosses were originally used to carry out a death sentence. Forcing people to cross the desert in places where it is more deathly is like sentencing people to die . . . The vertical part of the cross stands for life: when we are alive we are usually erect. The horizontal part represents death, parallel to the ground. The point where the vertical and the horizontal meet, the heart of the cross, is where compassion lies. This is where I want to be. Every cross I make and put out there is a concrete act of compassion.30

Alvaro’s crosses do not only represent death; they are material evidence that migrants lived. If the vertical panel of the cross embodies life because “when we are alive we are usually erect,” the crosses point not only to a terrible loss suffered. They describe that person’s entire journey; they map the body’s movements across geopolitical borders. The crosses invite us to accompany the migrant from start to end, from movement to lifelessness. In doing so, we witness the individual’s whole story, not just their tragic ending. As Alvaro explains, this is where compassion stems from.

Alvaro makes the 42-inch crosses by hand with lumber that he himself purchases. He plants four crosses each week and is now close to reaching three hundred crosses placed in the Sonoran desert. Friends and people who accompany him on these trips donate leftover paint from home-improvement projects, which is why the crosses vary in color: red, orange, blue, purple, grey, etc. What does not vary from cross to cross is the red dot in the center, referencing the red dots on the Humane Borders maps. He decorates each cross with tin cans found on migrant trails.

When I asked him to explain the tins cans, Alvaro responded: “Every discarded can out there has a story to tell, it may even contain traces of the DNA of the person who ate its contents. Every cross of course has my DNA, so I leave something of myself out there. It is my connection to la raza.”31 Alvaro links his own body not only to the deceased’s but also to all migrants and to the objects and spaces around him. The importance of objects—apart from serving to help identify deaths—lies in their potential to speak, to reveal something about the individual who no longer has a voice. They tell the story of a migrant who paused to eat what may have been their last meal; they are often the only remaining physical traces of people’s presence in the borderlands.

The Performance of Mourning

Each cross planted is a performance, as Alvaro and his team use their bodies, objects, “sacred items and symbolic processes” to mourn dead migrants.32 Of particular interest here is the liminality of Alvaro’s team and the migrants their work honors. Not only are migrants “betwixt and between” their home and receiving countries and life and death, Alvaro and his team are also liminal entities in the sense that they engage in a “state or process which is betwixt-and-between the normal, day-to-day cultural and social states and processes of getting and spending, preserving law and order, and registering structural status.”33 Alvaro’s volunteers—most of whom are white, U.S.-born Americans with the freedom of mobility denied to Latinx migrants—abandon their normal routines and spaces of daily living to both literally and figuratively enter the desert and participate in the performance of mourning.34 Each time we board the red Samaritans truck, stop for shitty breakfast, hike to the location where the migrant died, and plant a cross, we enter liminal spaces and places, setting ourselves apart from the routine—read: secular—world. We become “neither here nor there . . . betwixt and between;” we are transformed.35

Mourning migrants through performance allows Alvaro and volunteers to deal with “incomplete mournings” in our own lives. The artist notes: “I am always amazed by how sentimental people get when they carry a cross, stand on the spot where the remains were recovered, help in the planting of the cross. Some people cry, some pray, others take time to reflect on losses they have suffered in their own lives.”36 By participating in the planting of the cross, we gain new insight into our personal losses. We are bonded together through this shared experience. This is how “communitas” develops, from the margins and in liminality.37 Communitas emerges out of the performance of mourning, when we—the volunteers—gather together in the desert, when we reject the labels imposed on migrants by dominant society, when we, regardless of our social status or position, labor together to honor those who perished alone, when we recognize they are not that different from us.

By participating in the ritualized performance of mourning, Alvaro, other Samaritans, and temporary volunteers such as myself are able to interact with one another and with the migrants whose deaths we are honoring. When our bodies come into contact with the dead, we mourn, we experience grief together, and we are changed. This transformation, however, cannot take place without the ghost’s involvement.

The Power of Ghosts

The performance of mourning requires the participation of the ghosts haunting the borderlands. These are the ghosts of the bodies out of place, the “bodies that have not been properly mourned and buried . . . haunting and restless reminders of life out of order.”38 In mourning these bodies, Alvaro restores order, arguing that people who die crossing an imaginary line exist, that their deaths matter, that their graves should be marked and recognized as such. In listening to their pleas, Alvaro allows the migrants to rest, to lie in peace.

The key to the performance of mourning is that the dead are still included as agents; they are bound into human sociality. The dead haunt the borderlands, crying out for justice and recognition. The dead speak, and what they have to say is powerful. As Trevor Hoag writes, “not only [do] those who mourn/grieve exert an often unquenchable affective force, but the dead/forgotten [also] have power.”39 Through the objects they left behind, the footsteps that outline their journey, and the absence their deaths mark in their communities, the dead command our attention. Their unheard stories demand a captive audience.

Drawing on Avery Gordon’s scholarship, we realize “following ghosts . . . is about putting life back in where only a vague memory or a bare trace was visible to those who bothered to look . . . to understand the conditions under which a memory was produced in the first place, toward a counter-memory, for the future.”40 Alvaro’s art can be understood as a lesson in human ethical relations, a lesson that uses the dead and invokes ghosts as sources of knowledge. The ghosts Alvaro chases are indeed only a vague memory, yet they did leave behind a bare trace, if only someone would bother to look or listen.

The dead have power; they stir up affective possibilities in the volunteer’s life. Although we are mourning strangers, in carrying a cross, walking through the desert for hours, digging and planting this object, not only do we honor the dead, the dead work to transform the volunteer’s life as well. In communing with the ghosts of the desert, I was changed.41 Speaking with Alvaro, I am sure he has been changed by this work, too.

The Politics of Countermemory

Because we never met the deceased, Alvaro asks his volunteers to “mourn simply for lives lost, for deaths in our own backyard that should not have happened.”42 When he speaks of these deaths as something that “should not have happened,” as tragic, avoidable, and premature, Alvaro counters U.S. government’s strategy of prevention through deterrence. He questions the creation of a war zone between the United States and Mexico in which each death is simply a casualty in the battle for territorial sovereignty. His artwork speaks directly to gender scholar Judith Butler’s questions when she asks, “Who counts as human? Whose lives count as lives? And, finally, what makes for a grievable life?”43 In counting migrant deaths as “grievable,” unjust, and worthy of mourning, Alvaro argues that yes, migrant lives count. Theirs are grievable lives, no matter how intensely the state attempts to erase their losses.

This is mourning as resistance, as dissent. Similar to the public altars that sprung up across the United States following the death of Korryn Gaines and other black female victims of police brutality, Alvaro demands visibility for bodies not deemed worthy or respectable in public consciousness. Black Feminist Future, the group organizing the altars for black women wrote in a statement, “We see the building of community altars as a way to take up public space, to mourn and grieve collectively and publicly, to . . . center and amplify black women and girls we have lost.”44 Whereas Black Feminist Future’s altars are produced by the affected community and intended to be publicly visible, Alvaro’s crosses are planted by outsiders and are for the most part invisible. Yet, both Black Feminist Future and Alvaro Enciso’s projects attempt to reclaim power and dignity within an environment where black, brown, female, and migrant bodies are extremely vulnerable to state and structural violence. Because the deaths of black women and undocumented migrants are so often blamed on the victims themselves—Korryn Gaines should not have been armed; that migrant should not have crossed the border—these projects serve as counter-narratives and countermemories.

Alvaro believes most of the crosses will not be seen by anyone apart from an occasional hunter, a lost migrant, or a rancher looking for a stray cow. The apparent anonymity of Alvaro’s crosses parallels the anonymity and invisibility of migrant deaths. In his work on memory and countermemory following World War II, James Young asks, “how better to remember a destroyed people than by a destroyed monument?”45 In considering Alvaro’s crosses, I ask, how better to remember an invisible people than through invisible crosses? Could there be a more fitting tribute?

While it is certainly a possibility that no one will ever see his crosses after they are planted, Alvaro pushes back against this invisibility by inviting volunteers and other observers to participate in and witness his project. Alvaro believes “the people who know about my project, who help me plant them, who take pictures of the crosses, can perhaps be touched in some way by this project . . . and that takes it out of its anonymity.”46 Alvaro’s emphasis on witness can be better understood by looking at The Samaritans’ mission statement: to be a witness in the desert. The Samaritans website states that their “primary purpose is to witness what happens on the roads and trails. It is important to observe what happens and tell friends, family, and the world what we see.”47 To witness is to expose the invisible and the hidden; this is Alvaro’s mission.

Alvaro’s project, which he has mythologized as “art without a viewer,” is a conversation between the artist, the person who carries and plants the cross, and the deceased—who even in death play a key role in the performance of mourning.48 Alvaro follows the ghosts and chases their stories; he provides “a place, a stage [for the ghost] to manifest or to perform.”49 His artwork allows the ghosts to take center stage.

As Alvaro’s art gains visibility through the individuals who spread the story, we are drawn closer to something lost, something barely visible, something we were never meant to see. In uncovering silenced deaths—indeed, a silenced history—these crosses help forge a countermemory and a counter narrative. Unlike Young, who uses countermemory in relation to his notion of the countermonument—“memorial spaces conceived to challenge the very premise of the monument,”—I use countermemory to signify a push against the tendency to “silence the past” and render certain bodies invisible.50 Alvaro’s artwork introduces the viewer to people who die and decompose secretly but whose stories challenge ideas of who belongs, who counts as human, and what it means to draw a line in the sand and condemn those on one side to death if they dare trespass. It calls them back into existence, into view.

By placing crosses and painting red dots on the landscape, Alvaro remaps the border as a place of death rather than just an assemblage of fences and military technology. By placing the crosses on state-owned land and claiming a burial place for the deceased, his project challenges the state’s ability to demarcate and define who does and does not belong. The Sonoran Desert is not just a hyper-militarized zone, nor is it just territory that divides two nation-states. It is a cemetery for thousands.

Conclusion

Alvaro and his team may very well be the last people to visit these sites of tragedy. Yet the crosses are meant for the volunteer just as much as they are for the deceased. When I journeyed with Alvaro and planted the first cross for Emilio Trinidad who died of hypothermia in 2004, when I spoke his name, when I imagined this could have been my father or my cousin, since I am also a migrant and my family also came to this country sin papeles (without papers), I allowed myself to feel. I was connected to him; I embraced the haunting. This, in and of itself, has tremendous power.

Recalling Anzaldúa’s understanding of the U.S.-Mexico border as an open wound, a permanent scar, I close this conversation with Ahmed’s call to “rethink our relation to scars.” She argues that

a good scar is one that sticks out, a lumpy sign on the skin. It's not that the wound is exposed or that the skin is bleeding. But the scar is a sign of the injury: a good scar allows healing, it even covers over, but the covering always exposes the injury, reminding us of how it shapes the body . . . This kind of good scar reminds us that recovering from injustice cannot be about covering over the injuries, which are effects of that injustice; signs of an unjust contact between our bodies and others. So 'just emotions' might be ones that work with and on rather than over the wounds that surface as traces of past injuries in the present.51

If a “good scar” sticks out, Alvaro’s crosses are just that. They dot the desert as reminders that the injury happened and continues to happen every day. In exposing the injuries—the open wounds—Alvaro fashions a stage for the ghosts to speak, creating opportunities for them to share their silenced stories. Dancing among the ghosts for an entire summer, I listened and am now repeating what I heard, over and over again.

Notes

Notes

1. The Tucson Samaritans was founded in 2002 as a mission of Southside Presbyterian Church. Their website describes the group as a “voice of compassion, a healing presence in the Arizona desert.” Members include religious and community leaders, volunteer doctors, emergency medical technicians (EMTs), and nurses, as well as bilingual volunteers and other “people of faith and conscience.”

2. I do not italicize Spanish because to italicize means to differentiate it as the ‘foreign’ language, which for me is English. Chicana scholar Gloria Anzaldúa believed such italics have a “denormalizing, stigmatizing function and make the italicized words seem like deviations from the English/white norm.” Gloria Anzaldúa, The Gloria Anzaldúa Reader, ed. AnaLouise Keating (Durham: Duke University Press, 2009), 10-11.

3. Los Tigres del Norte. Uniendo Fronteras. Fonovisa Records, 2001, CD.

4. Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, (San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1987), 3.

5. Luis D. León, La Llorona’s Children: Religion, Life, and Death in the U.S.-Mexican Borderlands, (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2004), 18, 250.

6. I use “border regime” to signify the complex systems and structures in place to monitor and control migration along the U.S.-Mexico border. This includes, but is not limited to, Operation Gatekeeper, Operation Hold The Line, Operation Safeguard, and the Secure Fence Act of 2006, all of which were implemented and are enforced by the United States Border Patrol, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, and The Department of Homeland Security.

7. Humane Borders is a faith-based organization that provides water stations along migrant trails in Arizona.

8. As Dr. Gregory Hess of the Pima County medical examiner’s office explained to me over the phone, the body can be identified in a number of ways. Fingerprints, tattoos, and marks can help identify the body, as well as objects found on the person such as ID cards, photographs, and phones. It also helps if the family has issued a missing person alert. If a match is made, the body is released to the family or appropriate person(s) for burial. However, if attempts to identify the body fail, they are released from the medical examiner for burial in a local cemetery. The sites where Alvaro plants his crosses then mark where the migrant died, not their final resting place.

9. We left our gallons of water next to each cross with the hope that they would be found by migrants passing through.

10. Alvaro Enciso, author’s field notes, July 8, 2015.

11. Michel-Rolph Trouillot, Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (Boston: Beacon Press Books, 1995).

12. Ibid.

13. A Congressional Research Service report published in 2010, “Border Security: the Role of the Border Patrol” details the government’s regime of territorial management and security. The report explains the government’s policy of “rerouting the illegal border traffic from traditional urban routes to less populated and geographically harsher areas.”

14. World Bank, “Mexico - Income Generation and Social Protection for the Poor,” A Study of Rural Poverty in Mexico 4 (2008): accessed May 6, 2016, https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/8286

15. Josiah McC. Heyman, “‘Illegality’ and the U.S.- Mexico Border: How it is Produced and Resisted,” in Constructing Immigrant ‘Illegality’: Critiques, Experiences, and Responses, ed. Cecilia Menjivar et al. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 112. doi:10.1017/cbo9781107300408.006.

16. Sarah Azaransky, “Introduction: The Border and the Borderlands,” in Religion and Politics in America’s Borderlands, ed. Sarah Azaransky (Plymouth: Lexington Books, 2013), 3.

17. “Warning Posters,” accessed April 1, 2016, www.humaneborders.org/warning-posters/

18. This is likely a low estimate as some bodies are never found or identified. “Custom Map of Migrant Mortality,” accessed April 1, 2016, www.humaneborders.info/app/map.asp

19. Daniel E. Martinez et. al, “Structural Violence and Migrant Deaths in Southern Arizona: Data from the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, 1990-2013” Journal of Migration and Human Security 2 (2014): 276. doi:10.14240/jmhs.v2i4.35.

20. Azaransky, “Introduction,” 3.

21. Martinez, “Structural Violence,” 275.

22. Joseph Nevins, Operation Gatekeeper and Beyond: The War On "Illegals" and the Remaking of the U.S. - Mexico Boundary (New York: Routledge, 2010), 180.

23. Ibid, 120.

24. Sarah Ahmed, The Cultural Politics of Emotion (New York: Routledge, 2004), 1.

25. Anzaldúa, Borderlands/La Frontera, 3.

26. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, March 30, 2016.

27. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, March 31, 2016.

28. Ahmed, Cultural Politics, 85.

29. Ibid.

30. Ibid.

31. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, March 30, 2016.

32. Victor Turner, “Frame, Flow and Reflection: Ritual and Drama as Public Liminality,” Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 6 (1979): 470. doi:10.18874/jjrs.6.4.1979.465-499.

33. Turner, “Frame, Flow and Reflection,” 465.

34. I use Latinx as a non-gendered term in order to avoid the androcentric, heteronormative term Latino. The popular terms Latino/a and Latin@, while attempting to be inclusive, still assume a gender binary.

35. Victor Turner, “Liminality and Communitas,” in The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure (Chicago: Aldine Publishing, 1969), 95.

36. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, March 30, 2016.

37. Turner, “Liminality and Communitas,” 465.

38. Erika Doss, Memorial Mania: Public Feeling in America (London: The University of Chicago Press, 2010), 102.

39. Trevor L. Hoag, “Ghosts of Memory: Mournful Performance and the Rhetorical Event of Haunting (Or: Specters of Occupy),” Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 10 (2014): 9.

40. Gordon, Ghostly Matters, 22.

41. Hoag, “Ghosts of Memory,” 5.

42. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, April 1, 2016.

43. Judith Butler, Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London: Verso Books, 2004), 20.

44. Jamilah King, “Altars for Korryn Gaines, Other Black Women Killed By Police Pop Up in Several Cities,” Mic, August 9, 2016, accessed August 10, 2016, https://mic.com/articles/151051/altars-for-korryn-gaines-other-black-women-killed-by-police-pop-up-in-several-cities#.gQ8VFhrFQ.

45. James Young, At Memory’s Edge: After-Images of the Holocaust in Contemporary Art and Architecture (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2002), 96.

46. Ibid.

47. “Go On A Desert Trip,” last modified January 2016, www.google.com/intl/en/privacypolicy.html.

48. Alvaro Enciso, e-mail message to author, April 1, 2016.

49. Hoag, “Ghosts of Memory,” 18.

50. Young, At Memory’s Edge, 96.

51. Ahmed, Cultural Politics, 202.

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.med.2016.3

1. Barbara Sostaita, "Making Crosses, Crossing Borders: The Performance of Mourning, the Power of Ghosts, and the Politics of Countermemory in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands," Mediation, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016), doi:10.22332/con.med.2016.3

Sostaita, Barbara. "Making Crosses, Crossing Borders: The Performance of Mourning, the Power of Ghosts, and the Politics of Countermemory in the U.S.-Mexico Borderlands." Mediation. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016). doi:10.22332/con.med.2016.3