Oren Baruch Stier is Professor of Religious Studies and Directs both the Global Jewish Studies Program and the Holocaust and Genocide Studies Program in the Steven J. Green School of International & Public Affairs at Florida International University. He is author of two books, Committed to Memory: Cultural Mediations of the Holocaust (2003) and Holocaust Icons: Symbolizing the Shoah in History and Memory (2015) and co-editor of Religion, Violence, Memory, and Place (2006). His research addresses Holocaust testimony, Jewish memory, Holocaust education, and the material and visual culture of the Shoah and its remembrance.

The indexical artefact succeeds in calling forth its previous users: those who have intermingled with it. In looking at the artefact one must engage with the traces of use, and in engaging with these traces one is touched by them.

Ellen Sampson, Worn

How This All Began: Holocaust, Religion, and Material Culture

In the summer of 2023, Laura Levitt and Oren Stier co-facilitated an interdisciplinary research workshop at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum under the auspices of the Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust, a branch of the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies at the USHMM.1 Our workshop, “Interrogating the Sacred: Holocaust Objects and their Care,” brought us together with eleven scholars and practitioners from the U.S. and overseas for ten days over a two-week period to learn from each other, conduct and present our research, and explore and tour the USHMM collections and exhibitions as well as other sites in Washington, DC.2 We were joined by members of the USHMM staff and a guest conservator, some of whom participated in all or part of the workshop.3 The workshop itself coalesced after several years of planning and preparation, including a COVID-caused delay of a year, which we used to meet via Zoom while developing themes and research perspectives, identifying objects and materials for further investigation, and bonding virtually. This close collaboration continued into our time together in person in 2023, through seminar discussions, presentations of specific objects, field trips, and informal gatherings.

Throughout our planning and execution of the workshop we sought to consistently center the Holocaust object itself, however defined, in our discussions and deliberations. Indeed, our work builds on a series of material turns in the humanities and social sciences. It prioritizes what it means to center “stuff.”

- 1

This special issue and the workshop before it came out of abiding work produced by the co-editors over the past decades. Oren first began writing about the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) and some of the objects housed and displayed there in his books Committed to Memory: Cultural Mediations of the Holocaust (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003) and Holocaust Icons: Symbolizing the Shoah in History and Memory (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2015), and, in particular, in his essay “Torah and Taboo: Containing Jewish Relics and Jewish Identity at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum,” in Relics in Comparative Perspective, edited by Kevin Trainor, special issue of Numen: International Review for the History of Religions 57, nos. 3/4 (2010): 505-536. The issue also builds on Laura’s work with family photographs, images carried to the camps from life before the Holocaust in American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust (New York: New York University Press, 2007), and then in her work on material objects and Holocaust memory in The Objects that Remain (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2020).

- 2

Workshop participants were, in alphabetical order, Caroline Sturdy Colls, Lisa Conte, Kate Yanina Gibeault, Yaniv Feller, Tahel Rachel Goldsmith, Koji Lau-Ozawa, Barbara Mann, Jennifer Rich, Christine Schmidt, Dan Stone, and Hannah Wilson.

- 3

USHMM staff who participated in all, or part of the workshop were Rebecca Carter-Chand, Scott Homolka, Jane E. Klinger, Alexandra Drakakis, Colleen Rakemaker, Heather Kajic, Julia Liden, Zachary P. Levine, Travis Roxlau, and Robert M. Ehrenreich. Julia Brennan joined as a guest conservator.

These turns take seriously the power and importance of objects in recasting how we think about history and memory.4 During the workshop, we considered the ways that some Holocaust objects are imbued with “sacredness” by survivors, museum professionals, scholars, or the public—on account of their biographies and provenance, through rituals of tender care, by way of proximity to the events they witnessed, and in terms of what these objects meant and mean to those who encountered them or to whom they once belonged. We explored questions of what makes an object “sacred” and what it means to care for such objects.

Some of the questions that motivated our conversations included: How are objects that are sacred, holy, or numinous distinguished from those that are profane or quotidian, and who decides how they are classified? How can we create a shared vocabulary around these terms? Does the dichotomy of sacred/profane offer a useful framework in which to conduct our work? What about sacrality’s inverse: desecrated, evil, haunted, or cursed? Moreover, how does trauma or an object’s proximity to violence alter its ontology? Can objects become sanctified through trauma and violence?

Additional questions relate to objects’ contexts: How do academics and practitioners, institutions, museums, libraries, and other organizations differ in their understanding of which objects in their collections are considered sacred and how they care for them? How do curation, conservation, and holding imbue otherwise inanimate objects with new life? What ethical and practical issues do museums consider when conserving, storing, and displaying sacred objects, particularly regarding objects’ cultural and religious contexts? How can these considerations of museum professionals be used to deepen museum visitors’ understanding of the Holocaust and other difficult histories? Finally, how do these discussions mark a material turn in scholarship around such legacies?

As scholars of religion, we have always been engaged in interdisciplinary work, bringing together history, memory, and visual and material culture, along with literature, film, museums, and other cultural manifestations. These are the ways we have come to approach Holocaust studies; in this instance, we wanted to focus our attention on the power of Holocaust objects, especially at this important historical juncture where, as survivors are aging and dying, we see our work shifting from an engagement with lived memory towards new interactions with recent history.

This special issue—and our respective work—are situated at the intersection of memory studies, religious studies, and material culture in Holocaust studies. Beyond the critical historical research long associated with Holocaust studies, the preceding workshop and now this special issue bring an interdisciplinary vision to our work as scholars, acknowledging not only academic expertise but also that of crucial museum professionals, including conservators, curators, archivists, cataloguers, registrars, and collection managers, among others. They not only make our turn to material artifacts possible but also have a great deal to teach us about the sacred nature of these objects and the tender regard necessary for their care. In other words, this collection has tried to honor and acknowledge the full range of knowledge producers whose work often goes unseen—those museum and collections professionals who work behind the scenes at places like the USHMM’s David and Fela Shapell Family Collections, Conservation and Research Center in Bowie, Maryland (the Shapell Center), home to the Museum’s archive, storage facility, library, and conservation labs.5 Part of what we hope readers will take away from this special issue is the power and importance of these often-invisible labors, making visible the work of those who tend to Holocaust objects.

- 4

These scholarly turns to material culture constitute a vast body interdisciplinary literature. Some of these works, representing some of the fields appearing in this special issue, are listed here. First and foremost, we want to acknowledge some of the critical work in our own field of religious studies including: MAVCOR Journal and the journal Material Religion; S. Brent Plate, ed., Key Terms in Material Religion (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2015); Sally Promey, ed., Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2014); and Deborah Dash Moore, ed., Vernacular Religion: Collected Essays of Leonard Norman Primiano (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2022). In Holocaust studies, we include not only our own work but critical scholarship by Marianne Hirsch, especially The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture After the Holocaust (New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2012); James E. Young, The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016); and Jennifer Hansen-Glucklich, Holocaust Memory Reframed: Museums and the Challenges of Representation (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2014). In Jewish Studies we are inspired by works such as Laura Leibman’s The Art of the Jewish Family: A History of Women in Early New York in Five Objects (New York, NY: Bard Graduate Center, 2020); and Gabrielle Berlinger and Ruth von Bernuth, ed., The Lives of Jewish Things: Collecting and Curating Material Culture (Detroit, MI: Wayne State University Press, 2025). In history, we include Leora Auslander and Tara Zahra, eds., The Objects of War: Material Culture of Conflict and Displacement (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2018). And, finally, in Literary and Cultural Studies, we have been particularly influenced by Bill Brown, ed., Things (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2004), and Maurizia Boscagli, Stuff Theory: Everyday Objects Radical Materialism (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

- 5

“The Shapell Center: Building and Preserving the Collection of Record,” United States Holocaust Museum, accessed May 13, 2025, https://www.ushmm.org/collections/the-museums-collections/the-shapell-center .

Fig. 2 Interrogating the Sacred: Holocaust Objects and their Care workshop participants view artifacts in the Shapell Center, July 31, 2023. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Photographer: Joel Mason-Gaines.

Towards these ends, we were able to bring together in the workshop scholars, educators, and professionals working with material culture, scholars engaged in archeological and anthropological work, as well as scholars of literature, history, and religion, not all of whom are engaged with the study of the Holocaust. This interdisciplinarity was greatly enhanced by the presence and active participation of those involved in the Material Culture Initiative at the USHMM.6 We were also fortunate to have had scholars at various stages of their careers, from graduate students to more established scholars, participate in the workshop. As we had hoped and imagined, others from the Mandel and Rubenstein Centers joined us for portions of the workshop, and some later contributed to this special issue. Our vision for the workshop and now for this special issue has always been to create a diverse interdisciplinary conversation where scholars and museum professionals could learn with and from each other.

In part we begin with the workshop and the Holocaust objects at its center because they so profoundly shaped this special issue. Indeed, we deliberately met for the workshop’s first two days at the Shapell Center so that our initial impressions and discussions as a group would focus not on objects already on display at the USHMM but rather on objects as they are held and stored, conserved and preserved, in order to highlight the processes and care involved—and even to reveal prior acts of tender regard critical to the objects’ care, including acquisition, accessioning, researching, cataloging, and more. We traced the voyage of newly acquisitioned materials into the collection, meeting and hearing from archivists, curators, and collection managers. We learned from conservators working with various media, including paper; three dimensional objects made of wood, metal, and glass; and textiles.

- 6

The aim of the Initiative is to enhance understanding of the Holocaust, both within and beyond the walls of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, through the incorporation of methodologies from material culture studies into Holocaust research and teaching. Current members of the Initiative include Robert M. Ehrenreich, Zachary P. Levine, Julia Liden, and Gretchen Skidmore.

Although these essays build on several presentations and discussions during the workshop, we also feature additional essays that cover a range of objects in the USHMM’s collection as well as Holocaust objects held in other museums, libraries, archives, and center collections. In addition, essays now include works not only by those who were official participants in the workshop but also by USHMM staff members and others. Moreover, many of the pieces were written or rewritten in response to the workshop, emerging out of our collective experiences learning with and from those at the Shapell Center who shared their expertise, their practices, and their collection with us. Alas, not all workshop participants are represented here, but the themes and concerns raised in each of these pieces are in conversation with those raised before, during, and after the workshop. This is the dual meaning of our title, “Tending to Holocaust Objects,” not only attending to the care taken regarding these materials, but also an orientation that leans towards those objects themselves and their intrinsic value.

In some of what follows here we want to consider our title, “Tending to Holocaust Objects,” and share some glimpses of our collective engagement behind the scenes to offer a clearer sense of how the sacred nature of these artifacts come to bear on the ways they are handled, and vice versa—the tender regard of those who do this work not only at the USHMM but in other settings, other collections of not only Holocaust objects. Indeed, as Laura explains in The Objects that Remain, these practices connect our work in Holocaust studies to other sites of traumatic loss, of individual and collective experiences of violation and genocide.7 Thus, this special issue invites and encourages comparison with and reflection on material remnants from other historical episodes of atrocity.

- 7

Laura Levitt, The Objects that Remain (University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2020).

Holocaust Objects

What are Holocaust objects and what makes them so compelling of our respect and tender regard? As the essays collected here make clear, these artifacts tell powerful stories about those who suffered and died and those who survived horrific acts of violation. The relationship between these once ordinary objects and the people who held, wore, and saved these precious things demands our attention and our care. Because these stories fill these objects with presence and urgency, they allow us to see the past breaking into the present, and that in turn produces a form of reverence.

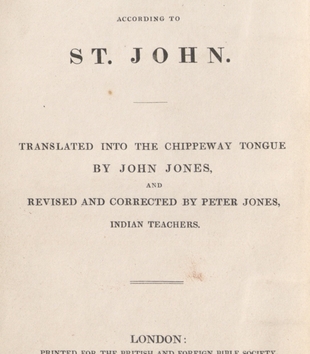

These items include a full range of intimate, familial and personal possessions from life before–a once beloved blouse, a photograph, a pocket bible, a ring or a wristwatch but also prisoner uniforms, wooden shoes, a tin bowl, or a spoon. Among these various essays readers will be introduced to objects held in camps and ghettos, small intimate gifts created in these places, a tiny book, a bracelet, a broach. They include ritual objects, a tallit katan that belonged to a small boy who had it with him as he and his family boarded the ship, the St. Louis, en route to the U.S. only to be turned back to Europe. It includes wedding dresses—one a prized possession from before the war, a reminder of a joyous occasion in the past, and two dresses made and acquired after liberation by former camp inmates in DP camps where they reimagined their lives after—hopeful signs of renewed life. There are texts that are themselves Holocaust objects, including precious letters lost and found from within the whirlwind. They include the maps and memories gathered after the Shoah in precious communal repositories, Yizkor books alongside key documents, a passport that made survival and escape possible. There are forensic archeological finds, some newly discovered—a ring, a name tag, dentures—and the very containers that held precious papers and other possessions—a briefcase, a valise, a trunk or any number of suitcases confiscated or later recovered. These artifacts are only some of the items discussed in these pages. Some of these items are or were conventionally understood to be sacred objects—a missal, a rosary, a mezuzah—while so many others, once ordinary objects marked by violence, have become sacred by their proximity to genocide, to the lives and bodies of those who died and those who survived.

Affective Engagement and the Sacred

Even in bits and pieces, the stories of these objects draw us in, make them come alive, touch us, as Sampson suggests in our epigraph. They tug at our hearts, and they disturb us. These affective responses are part of how we consider these objects as sacred, or as former chief conservator at the USHMM and contributor Jane Klinger describes, as “numinous.”8 Many of the pieces addressed in this special issue evoke great pathos, while at least a few bring with them some disgust and discomfort. These designations are often bound not only to actual ritual objects but also to objects that are connected to those who died, intimate objects held close but also objects that bring this past back to us in the present. We have put this issue together around some of these sites. As Klinger has argued, without a sensitivity to the power of Holocaust objects and the range of emotions they evoke, those whose task it is to hold and attend to these collections could not do these jobs. Those who work with Holocaust materials are not alone in these affective engagements and sensitivities to the sacred nature of the artifacts that they care for. During the workshop we were fortunate to have had textile conservator Julia Brennan join us at the Shapell Center and, moreover, invite us to her home studio, where we were introduced to some of the objects she and her team were tending to in the intimacy of her workspace. Among these pieces was a bloody garment, an artifact of contemporary police violence against African Americans. Brennan has also done extensive work with the bloody garments of those slaughtered in the genocides in Rwanda and Cambodia, carefully working with these communities around the sacred nature of these painful relics.9

We understand this work as part of what it means to consider these objects sacred. Tender regard is a form of ritual even as these labors are professionalized. Indeed, we see these behind-the-scenes activities as ritual enactments of otherwise mundane professional tasks, whether in Brennan’s home studio or at the Shapell Center. In other words, well before we as scholars get to these repositories, the very handling of these artifacts by museum professionals signals something about their special status that is translated into the tone of our writing and speaking about them. To be clear, part of what we want to call attention to is the powerful relationship between the respectful labor of these museum professionals as it is interrelated with how those of us who are scholars engage with these materials.

- 8

We remain struck by Jane Klinger’s use of this kind of religious language to describe the aura around the Holocaust artifacts she works with. Although others have written about the agency of objects and their vibrancy, we are especially taken by the power of religious language and its ability to address the allure of such objects. Although scholars of anthropology have written eloquently about such agency, they tend to avoid any reference to religious discourse. See, for example, Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010). In sharp contrast to Bennett, both Laura and Oren have written extensively about icons (Stier, Holocaust Icons), relics, and reliquaries (Levitt, The Objects that Remain). Other works that describe such objects using the language of the sacred include, in art history, Cynthia Hahm, The Reliquary Effect: Enshrining the Sacred Object (London: Reaktion Books, 2017) and, in literary studies, Joe Moshenska, Iconoclasm as Child’s Play (Redwood City, CA: Stanford University Press, 2019).

- 9

Zoey Poll, “Preserving Brutal Histories, One Garment at a Time,” New York Times (January 22, 2021), accessed March 22, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/world/asia/conservator-textiles-atrocities.html .

The Essays

This interrelationship leads into the order and logic of the essays. This special issue is divided into five parts, each addressing a different cluster of concerns regarding Holocaust materials, their care, and their relationships to other legacies of trauma and loss. We begin behind the scenes with comparative and institutional questions and then move to the most intimate objects, those in closest proximity to the human body. From there we turn outwards, from items worn on the body to ritual-textual objects. Our concluding section addresses textual objects that communicate from the past to the present with the assistance of museums and other contemporary interpreters. Each section of the special issue is preceded by a brief introduction that sets the stage for the essays that follow.

Acknowledgments:

We want to thank a number of people at the USHMM, most especially Rebecca Carter-Chand, the Director of the Programs on Religion and the Holocaust (formerly the Programs on Ethics, Religion, and the Holocaust, or PERH) for sponsoring the workshop, the first to address material religion in relation to Holocaust history and memory at the Museum’s Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies.10 We are deeply indebted to Julia Liden who worked alongside us and helped imagine, organize, and carry out our workshop as PERH Program Coordinator. Julia is now a Senior Program Coordinator working on the redesign of the USHMM’s permanent exhibit. We are grateful as well to all the professionals who work behind the scenes at the Shapell Center through the David M. Rubenstein National Institute for Holocaust Documentation.11 We want to thank Robert M. Ehrenreich, Director of Academic Research and Dissemination at the Mandel Center who has been a valued advisor to us on both the workshop and this special issue. We also want to acknowledge Robert and Julia’s generosity, as members of the USHMM’s Material Culture Initiative, in supporting this project. We have all benefited greatly from their efforts. Finally, we are indebted to Sally M. Promey and Emily C. Floyd at MAVCOR Journal for believing in this special issue and helping us bring it to fruition.

- 10

“About the Mandel Center,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed March 22, 2025, https://www.ushmm.org/research/about-the-mandel-center .

- 11

“Rescuing the Evidence: David M. Rubenstein National Institute for Holocaust Documentation,” United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed March 22, 2025, https://www.ushmm.org/support/why-support/our-work-and-mission/rescuing-the-evidence .

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2025.11

Oren Baruch Stier and Laura S. Levitt, “Tending to Holocaust Objects: An Introduction,” Essay, MAVCOR Journal 9, no. 2 (2025), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2025.11.

Stier, Oren Baruch and Laura S. Levitt. “Tending to Holocaust Objects: An Introduction.” Essay. MAVCOR Journal 9, no. 2 (2025), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2025.11.