Sally M. Promey is Professor of American Studies and Professor of Religion and Visual Culture at Yale University. She holds a secondary appointment in the Department of Religious Studies and an affiliation with the Department of History of Art. She is Director of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion. Her publications include Painting Religion in Public: John Singer Sargent’s Triumph of Religion at the Boston Public Library (Princeton University Press, 1999) and Spiritual Spectacles: Vision and Image in Mid-Nineteenth-Century Shakerism (Indiana University Press, 1993). More recently she is co-editor, with Leigh Eric Schmidt, of American Religious Liberalism (Indiana University Press, 2012); and editor of Sensational Religion: Sensory Cultures in Material Practice (Yale University Press, 2014). Religion in Plain View: Material Establishment and the Public Aesthetics of American Display is under contract with University of Chicago Press

This essay was commissioned by the Columbus Museum of Art to appear in Reflections: The Columbus Museum of Art’s American Collection (Columbus: Columbus Museum of Art in Association with Ohio University Press, Athens, 2019). We publish it here with permission from the museum.

Like any number of legendary self-made Americans, Elijah Pierce was born in a log cabin.1 His particular cabin was located in Baldwyn, Mississippi, an area known for its logging industry. Pierce grew up on the land his father farmed (a plantation belonging to Lee Prather) and was well acquainted with the surrounding woods. At eight or nine years old, Pierce learned to carve under the tutelage of his uncle Lewis Wallace, his mother’s brother. “When I was a boy I was always carving,” Pierce said. His favorite Christmas gifts were pocketknives, the tools of his pastime and art.

From boyhood Pierce maintained a peculiar kinship with wood. Over his long life he attributed to it a number of significant capacities. Importantly for him, his work in wood connected him to people and people to each other. He noted his practice of investing his woodcarvings with prayers and good wishes whenever he gave them away, sending out blessings that inhabited the medium and its artistic treatment in his hands. He was confident in the power of the wood to contain and communicate his story and his history.

Obey God and Live (Vision of Heaven) is Elijah Pierce’s personal conversion narrative. In this piece of wood he depicted the definitive episode of his own spiritual autobiography, an event in his past that he understood to (re)organize, interpret, and frame his entire life. In selecting this material form to narrate the transformation he believed God elicited from him, Pierce gave tangible testimony to his convictions. He represented himself as the subject of divine intervention. He set his life inside the bounds of an authoritative sacred history. Elijah Pierce— within his own specific Afro-Protestant and Black Masonic contexts, his very name signaled his place in a biblical and prophetic genealogy.2

More than any other single image that Pierce carved, Obey God and Live (Vision of Heaven) represented, for him, the moment that most specifically and persuasively set out his destiny and vocation. In this carving, he brought the themes and cadences of Christian scripture and homiletic practice to bear upon the circumstances of his own existence and perspective. He showed that this miracle happened to him. He demonstrated how he was, in the process, touched directly by the large brown hand of God.

Pierce pictures this literal, tactile connection in his carving. He used gold glitter, relative scale, and placement within his composition to call the viewer’s attention to the space where the hand of God, issuing forth from a funnel-shaped energy field of light, comes into contact with Pierce’s own head. He would look back later and note that he had been marked since birth as a prophet or seer, as one with a religious vocation. He was born with a caul, relatives told him—a “veil,” he called it—that portion of the amniotic sac that sometimes covers a newborn’s head, interpreted from ancient times as a sign of calling, of being set apart for sanctity or prophecy or greatness of some other sort. In the world of earthly pleasures this kind of expectation can be burden as well as blessing.

- 1I am indebted to Melissa Wolfe of the Columbus Museum of Art for helpful consultation. I am also grateful to Michael Hall for an illuminating telephone conversation of June 20, 2011, as well as the content of his interviews with Elijah Pierce, provided to me in transcription by the Columbus Museum of Art. In the final editing of this manuscript, Anastasia Kinigopoulo, Assistant Curator, Columbus Museum of Art, provided invaluable assistance with content.

- 2For a compelling study of earlier, more broadly social uses of history-making and sacred storytelling among African Americans in the United States, see Laurie F. Maffly-Kipp, Setting Down the Sacred Past: African American Race Histories (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2010).

Obey God and Live, for all its apparent organizational simplicity, is sure and powerful in its narrative clarity. The story thread begins as Pierce joins his mother Nellie for the evening’s family bible reading (Fig. 2). The main event, occupying almost two-thirds of the surface of the board, concerns a stark choice: for or against obedience to God. This Pierce signified in the two books (labeled “Holy Bible” and “Sears Roebuck”) on the table between the representation of himself as a young man and the carved relief figure of his devout mother. In the common vocabulary of the period, this juxtaposition of Christian scriptures and a catalogue of appealing goods for sale might be expressed as a confrontation between “the Good Book” and “the Wish Book.” That the choice is his alone Pierce indicates by having the titles of both volumes face his direction. He underscores his responsibility and agency in his long reach across the table, over his still-closed bible, to the catalogue full of attractive new items for purchase. That his believing mother assists God in leading her son toward the right choice is beautifully narrated in the choreography of hands circling the white tabletop on the left side of the carving. Pierce’s open right hand in his lap and his mother’s left hand cradling her own open bible at her waist together bracket and anchor the tableau around the table. The placement of hands simultaneously focuses the viewer’s attention on the gentle but firm confrontation ensuing behind the lamp, as Nellie holds down the corner of the catalogue to dissuade Elijah from grasping it. One of Pierce’s older sisters looks on. A kind of witness figure, she stands with elbows jutting out (unseen hands planted firmly on hips). The Vs formed by her collar and arms provide directional cues, identifying the principal human protagonists and giving further visual emphasis to the weight of the mother’s gesture. We see five brown hands around the table. The fifth one, the largest and brownest, belongs to God, the hand of power and presence in Pierce’s rendition.

The right third of the image provides important details of the story (Fig. 3). The smooth curve of the back support of Nellie’s chair, simulating an elegant open parenthesis, leads the eye to the action. Like the pages of a book, this image reads from left to right and top to bottom. In the vignette at top right, Pierce, having chosen catalogue of fanciful goods over recitation of religious obligations, falls stricken as though dead to the floor, his body supported by the older sister in her two-tone (blue over purplish-red, slightly metallic) dress. In the final figural scene at lower right, Pierce’s body is laid out on a bed, doctor consulted and undertaker called. All this happens in the presence of a cloud of witnesses, the floating faces of neighbors, mostly gazing full-on at Pierce or looking out, in shock and incredulity, into the viewer’s space. Four figures in profile mark the image’s right margin and concentrate the story’s punch by closing the parentheses opened by the back of the mother’s chair.

We, the viewers, join this crowd of faces, rounding out the circle of spectators. Pierce, the artist, provides only one figural clue to the happy ending of his autobiographical Christian morality play. Narrative resolution hangs on a child, a smile, and the color red: we take our cues from his youngest sister’s hopeful expression, as she stands in the foreground, white ribbon in her hair, at the head of the bed. Her bright-red dress points back across the panel’s surface to its visual bookend in the less saturated red carved text at left: “Obey God and Live.” And live Pierce does, his sense of self, looking back, changed forever by this moment of divine intervention. Pierce understood this narrative as a miracle story more than a tale of judgment, though miracle and judgment are not antithetical here: “Obey God and live!” is but a short (though important) step away from “Obey God or die!,” as Pierce implied when he said, “I was laid out for dead once by not doing what the Good Lord told me to do.”1

From a psychological and spiritual perspective, in the midst of the conflict suggested between Good Book and Wish Book, this is a story of liberation, an assertion of the possibility of transformation, personal and social. Having a story, especially one manifested in material form that invites repetitive handling, viewing, and recitation, provides a way of organizing and getting hold of life’s uncertainties. Elijah Pierce may feel pulled in two directions, but he controls this story. He relates a narrative he understands as truth and he testifies to this accomplishment. As maker of the narrative, he has creative voice and authority: this is his image, his framing, his interpretation of events. Pierce tells a story of obedience to God, but as both subject and narrator of the story—as one who “knows” the outcome—this is in fact his “vision of heaven,” as the subtitle he selected asserts, his vision of power and life. Far from being subject to the crowds of white model consumers pictured in his Sears Roebuck catalogue, he answers here only to God.

Obey God and Live is about choice and will as well as obedience, about choosing the Good Book with its lasting spiritual rewards over the Wish Book with its glossy fleeting material promises. While he found the world of goods and parties attractive, Pierce depicts himself casting his lot with the God whose powerful dark hand anointed him just as surely as it recalled to mindfulness his religious obligations. In this woodcarving God’s hand descends in rebuke and consecration. This is a conversion story and a resurrection story. Pierce understood this visionary event as a demonstration of God’s sustaining and renewing expectations in his life.

Elijah Pierce located the production and circulation of his woodcarvings in a rich network of social activities and events. He sometimes carved alone, but more often worked in his Long Street barbershop, between clients and during conversations with them. Carving was an industrious pastime. It usefully occupied hands in times between people needing haircuts. In the process, it operated as meditative exercise, social network, personal memory, entertainment, devotional activity, and social commentary. Wood was a multifaceted medium for Elijah Pierce. His was a kind of performance art lodged in the routine of his daily life. He made space to exhibit many artworks, densely populating with relief carvings and three-dimensional figures-in-the-round the walls and surfaces of his shop’s duplex, a mirror image second room immediately adjacent to the first, with barbershop and art gallery occupying space under one roof. This set of practices with respect to his work in wood gave him ample opportunity to articulate, recollect, and reinterpret, over and over again, the stories manifested in his art. For Pierce, church (the Gay Street Tabernacle Baptist Church) and workplace (the Long Street Barbershop and Art Gallery) were not distinct sacred and secular spaces, as some have suggested, but rather two interwoven locations of personal devotion and conviction. His rooms on Long Street combined religious display with popular whimsy. Pictures of Jesus and of cigar-smoking, card-playing canines lived comfortably in a single space, each inflecting the other. In the barbershop, and in demonstrations of his artwork elsewhere, he acknowledged the power of this extra-ecclesiastical mixture: “I can get to a lot of people who don’t go to church, and change their lives.”2 He repeated, with singular frequency, the life-defining story pictured in Obey God and Live. The image remained in Pierce’s personal possession, on display in his barbershop. He never copied the carving; in fact, he generally declined to copy any of his images, believing that the pictures belonged to a particular vision, as revealed to him in a particular piece of wood. After the artist’s death in 1984, the Columbus Museum of Art acquired this carving from his estate.

When Elijah Pierce talked about Obey God and Live (Vision of Heaven), he consistently remarked that God had commanded not simply that he read the bible but that he read a “certain passage of scripture in St. Matthew,” somewhere “around the 16th chapter,” he recalled. While it is difficult to pin down precisely what might be meant by “around the 16th chapter,” it seems worth noting, given Pierce’s interest in “signs,” that Matthew 16 begins with a request that Jesus show a “sign from heaven” and moves from there to a declaration of Jesus as messiah. The chapter’s near-conclusion is perhaps most relevant to the experience Pierce pictured in this vignette, to his admission that he reached first for the Sears Roebuck catalogue, with its pages and pages of earthly goods, when God told him to read first the bible: “For what will it profit a man, if he gains the whole world and forfeits his life?” (Matthew 16:26). Pierce says as much in fewer words: “Obey God and Live.”

Much might be said about the specific sensory and material capacities of Pierce’s medium, about the kinds and qualities of the wood he selected, the tools he used to carve into it, the tactile experiences of working with it, the ways different grains and differently sanded surfaces felt to the hand, the smells (of sap and shavings and paint and varnish) it introduced to his home and barbershop. From a visual perspective, wood offered Pierce a particular set of characteristics as well. The one that arrests my attention at this moment concerns relations among media and color, and especially between this medium and the range of possibilities presented for skin color. Wood, unlike bleached paper products made from wood pulp and fibers, naturally appears in a range of beiges and browns. The most common and immediately available alternative media for inexpensive figural religious devotional and domestic decorative objects set a much lighter base standard. Chalkware, for example, like the bisque and parian wares and the more expensive kinds of porcelains and marbles they imitated, was, on its own gypsum-derived terms, the starkest of whites. When left unpainted in areas representing skin, or when merely coated in clear varnish, as was often the case, the default color was white, the “natural” base tone of the medium. In the context of twentieth-century racism and race relations in the United States, and when replicated over and over again in church and school and home and missions field, these objects (in medium as well as decoration) instantiated whiteness as the “usual” color for skin, human and divine—and this was especially the case in Christian educational and devotional pictures and objects.

Wood offered a different set of “natural” possibilities, and Elijah Pierce’s practice with respect to treatment of these surfaces suggests that he recognized these implications and pursued them. Medium thus took on an important, and literally substantial, narrative content. Pierce either painted the skin of his figures in a range of light to medium browns (often approximating the color of the wood itself, once varnished) or left faces and arms and hands unpainted, covering them only in varnish and letting the brown tones of the wood, accentuated by the darkening of aging shellac, represent skin color. While there are exceptions, Pierce’s figures can be taken to be dark-skinned, even when contemporary audiences thought they “knew” the figures to be white, as in the cases of Jesus or Abraham Lincoln, for example. Pierce’s representation of the ideal Universal Man (1937) made moving and sophisticated use of medium in this regard. His carving of the historic 1937 boxing match between Joe Louis and James Braddock shows the two fighters with the same varnished but unpainted wood skin tone, even though contemporary press and populace seemed determined to focus almost exclusively on the men’s racial difference.3 The medium Pierce used provided him with the opportunity to set “natural” or “neutral” skin tone in a darker shade of brown than the “neutral” or “natural” standard of porcelain or plaster or marble. The color that Pierce’s medium “naturalized” conformed to darker skin with greater facility than to pale. In Obey God and Live he underscored this commitment in his decision to render God’s hand in richest brown. He accomplished this by varnishing this area but letting the wood’s own natural (and naturalizing) brown show through.

In the 1930s and 1940s (two decades or so before the 1956 date he later affixed to Obey God and Live, but years after the transformative event it represented) Elijah and Cornelia Pierce took his carvings on the road, traveling to county fairs and churches and other available venues to engage in what they called “sacred art demonstrations.” In an interview he elaborated: “Every piece of work I got carved is a message, a sermon. Preacher don’t hardly get up in the pulpit and preach but he don’t preach some picture I got carved. My [second] wife and I did a lot of travel with those pictures…. Kentucky, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Kansas, Nebraska, Iowa, Illinois, and back to Columbus. People would ask me to comment on this picture, what that one means. My wife could talk about them near as good as I could. We never sold any tickets to our program, but everywhere we’d go, the program’d pay our expenses…”4 His work could also be viewed in their home, by appointment, and at his barbershop.

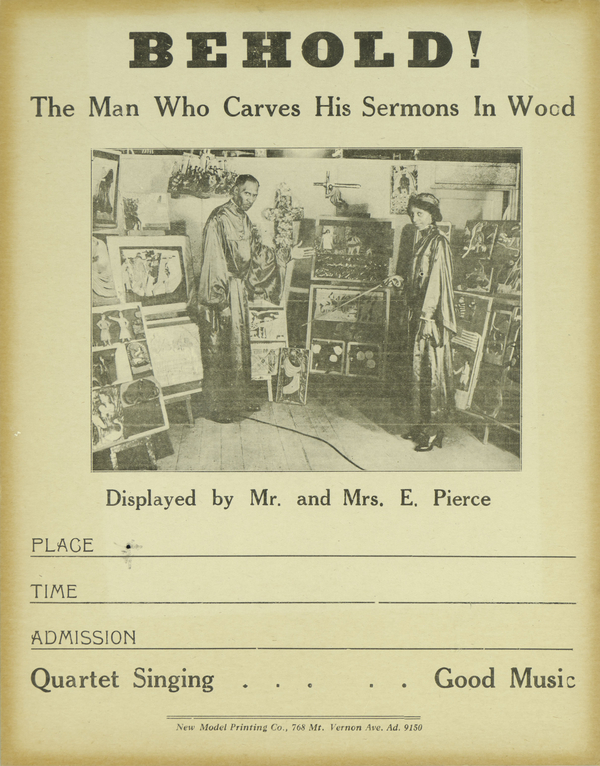

The broadsides that the Pierces and others produced to advertise these religious art displays, at home and on the road, cast the work in the common genre of objects performing important roles in American domestic missionary activity and Christian education. From the eighteenth century to the present, Christian individuals and institutions used a wide variety of pictures—large and small, handmade and manufactured, and in many media—in evangelization efforts. “BEHOLD! The Man Who Carves His Sermons In Wood” proclaimed one poster (Fig. 4), with the text situated as a masthead or title for a photograph of Elijah and Cornelia, in church vestments, preaching his sacred artwork. The many pieces displayed in the photograph include a Last Supper that Pierce fittingly carved into one of Cornelia’s breadboards (“This is my body broken for you, take and eat,” says the Jesus of Christian scripture and liturgy, in blessing and consecration, over the bread on the table before him). Pierce proved himself to be an effective material and performative interpreter of ritual and biblical vocabularies and phrasings. The broadside’s “behold the man who carves,” while overtly alerting potential audiences to the times and places of traveling displays, also wielded added weight and authority for biblically literate audiences in its iteration of an assertion concerning the story of another woodcarver of sorts, the story of Jesus the carpenter and his Passion: “Ecce Homo,” “Behold the Man.”

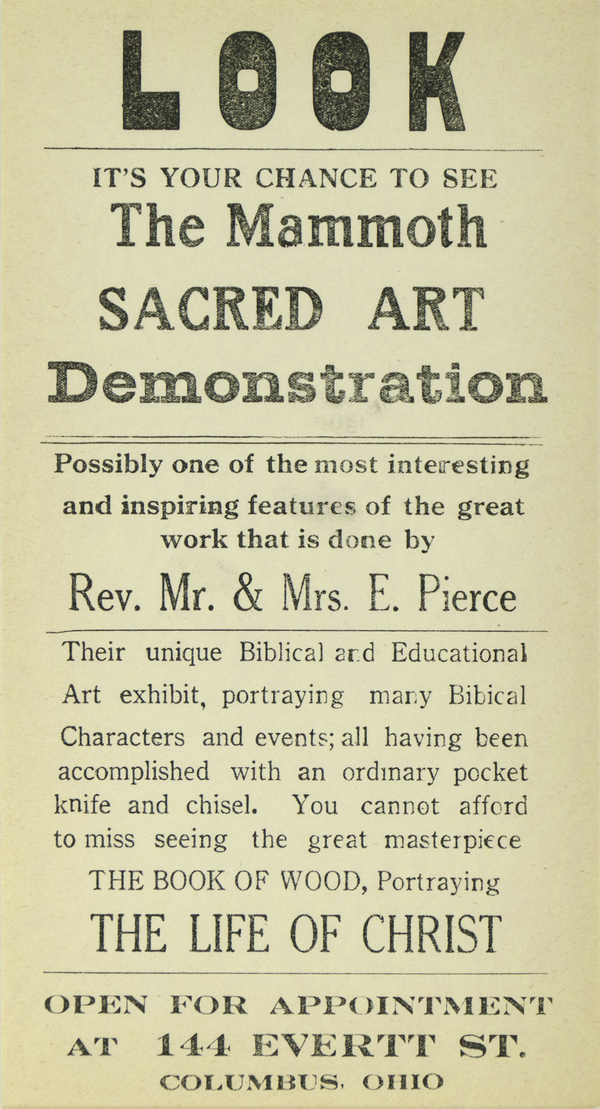

Another broadside, likely dated between 1944 and 1947 (Fig. 5), advertised work exhibited by appointment in Pierce’s home, exclaiming:

LOOK: It’s Your Chance to See The Mammoth Sacred Art Demonstration. Possibly one of the most interesting and inspiring features of the great work that is done by Rev. Mr. & Mrs. E. Pierce. Their unique Biblical and Educational Art exhibit, portraying many Biblical Characters and events; all having been accomplished with an ordinary pocket knife and chisel. You cannot afford to miss seeing the great masterpiece The Book of Wood, Portraying THE LIFE OF CHRIST. Open for appointment at 144 Ever[e]tt St. Columbus, Ohio.

Of his vocation as evangelist, Pierce said: “After running from the ministry for 20 years every time I refused to preach, He [God] made me carve it. As my wife told me, ‘God made you preach every sermon in wood.’"5

- 1From interview transcription in Elijah Pierce: Wood Carver, exh. cat., Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts, November 30–December 30, 1973.

- 2Mary Bridgman, “Primitives Keep Pierce Perking,” Columbus Dispatch, November 13, 1977, 1-5.

- 3See Nannette V. Maciejunes and E. Jane Connell, “Secular Sermons: Elijah Pierce, Woodcarver,” Timeline (a publication of the Ohio Historical Society), May/June 1993: 7.

- 4Caroline Jones interview with Elijah Pierce, n.d., quotation is from second page of transcript.

- 5Quotation is from a transcription provided by Columbus Museum of Art, header reads “Elijah Pierce: Sermons in Wood,” [4].

The forms of Pierce’s religious and moral narrative works, and his modes and venues of display, ingeniously combine two families of period Protestant evangelizing and devotional arts. First, when he and Cornelia took his work on the road, they generally attached individual carvings to larger portable walls or storyboards and publicized these traveling displays in broadsides of the sort already described. They thus put his sacred art into a pattern of circulation and religious educational and missionary consumption that also included such things as bible panoramas, large-scale figural displays sculpted of wax or other media, pictorial performances preachers and others called “chalk talks,” and “magic lantern” narrative light shows. Second, as separate, discrete objects, and thus in a smaller scale (Obey God and Live measures a bit over a foot high and just shy of two and a half feet wide), Pierce’s carvings resembled the scripture plaques, mottos, and testimonies marketed as devotional signage, pictures and texts in many media (wood, chalk, cardboard, plastic, metal) for use in home and church.

In whatever ways historians might categorize Pierce’s work, however, the artist himself emphasized the proximity between its material presence and its performance as story. As an object, Obey God and Live integrated Pierce’s own story with the biblical story just as it placed itself as a communicative sacred thing over against the mutely demanding commodities offered in the Sears Roebuck catalogue. For most of his long life Pierce did not sell his carvings but displayed them, performed them, preached them, lived with them, gave them away. Not intending to sell them, he often did not sign them. As late as mid–November 1977, Obey God and Live did not bear its central signature and date. Sometime within the last six or seven years before his death in 1984, Pierce applied these to his long-completed composition (which, based on style, was probably carved almost a decade earlier than the 1956 date upon which he settled). He most likely added name and date in response to mounting demand for his work, which in the early 1970s began to receive notice as “art,” as work commoditized for the market rather than as the creative production he performed for other personal, social, and religious purposes. Adding signature and date transformed the work under the new stress and expectation brought to it by external and limiting categorizations like “outsider” and “folk.” Still, Pierce held the piece out of commercial circulation, retaining possession of it through the end of his life.

Obey God and Live is the one work among Elijah Pierce’s woodcarvings that most succinctly expresses his own sense of self and sacred obligation. In this piece of wood he visualized the thesis he chose for his own life story. The question Pierce raised most explicitly was not whether he and, by implication, other Christians should deny themselves the pleasures of Sears Roebuck. The overt issue was this: When God commanded that some other activity be undertaken first, the “wish books” of the world should not interfere with obedience to God’s command. Whenever he was offered the opportunity to expand, Pierce maintained that the principal content of obedience to God was “love ye one another.”1

Pierce’s repeated textual references to Matthew 16 in relaying the significance of this story, however, indicate that he experienced some degree of personal tension in the particular set of options represented by the two books (bible and catalogue). This was not simply an event of the past but a present choice, one that required daily iteration and assent throughout his long lifetime.2 The story had a happy ending, but it retained, in the narrative loop of repeated retelling and in the object’s central material and visual place in his everyday life, a durable charge, a register of anxiety. Pierce understood the tale’s outcome to be positive, but the process and sequence of passage through “time,” in one vignette after another and in each telling or recollection, carried the remembered weight of something looking a lot like death before, as Pierce would say, “I came back just like I went away: like the sun comin’ from behind a cloud.”3

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2018.1

1. Sally M. Promey, "Elijah Pierce and Material Conversions," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018), doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2018.1

Promey, Sally M. "Elijah Pierce and Material Conversions." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 2, no. 1 (2018). doi: 10.22332/mav.ess.2018.1