Marie W. Dallam is Associate Professor of Religious Studies and Associate Dean of the Honors College at the University of Oklahoma. Her books include Cowboy Christians (2018) and Daddy Grace: A Celebrity Preacher and His House of Prayer (2007), and she is co-general editor of Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions. Her research focuses on religion and culture, particularly in relation to alternative and marginalized religious groups in the United States.

Sociologist Daniele Hervieu-Leger has written that religion is “a chain of memory,” implicitly drawing on existentialist thought to articulate how religion functions for communities. In a world in which change is near-constant and meaning is at best abstract, religion can offset a resultant ennui. Hervieu-Leger posits that, by cloaking themselves in specific religious “traditions” and a religious “history,” people find a validating identification with a faith community. She writes, “Continuity acts as the visible expression of a filiation that the individual or collective believer expressly claims and that integrates him or her into a spiritual community assembling past, present, and future believers. The heritage of belief fulfills the role of legitimizing imaginary reference.1" Put more simply: communities of faith understand their present in relation to a religious history that they believe to be true and authoritative. Though one might debate whether this is the primary function of religion or just one of its many functions, there is little denying the importance of religion’s ability to provide narrative framing for our lives.

What happens, then, when part of the religious history a person believes in turns out to be incorrect? A dissonance is created that must be addressed through new interpretations of past, present, and possibly the future. A revised history may combine with imagination to create a very different chain of memory. As Hervieu-Leger writes, a reinvented chain is formed through a “process of selective forgetting, sifting and retrospectively inventing."2 She sees this process of reinvention as part of what keeps religion flourishing. This article explores early indicators of a reinvented chain of memory unfolding in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—a faith that is itself grounded in a concept of historical restoration—due to a new public understanding of its history of polygamy.3 Specifically, I consider the example of contemporary visual art that interrogates and rearticulates memories of historical Mormon polygamy as one link in this new chain.

- 1Daniele Hervieu-Leger, “Religion as Memory: Reference to Tradition and the Constitution of a Heritage of Belief in Modern Societies,” in Religion: Beyond a Concept, ed. Hent de Vries (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 256. I extend my thanks to Christopher D. Cantwell for pointing my attention to the work of Hervieu-Leger.

- 2Daniele Hervieu-Leger, Religion as a Chain of Memory (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000), 124. Admittedly this line of questioning deviates from Hervieu-Leger’s intellectual project, which is more concerned with the fragmentation of collective memory, but her work speaks to it nonetheless.

- 3The full, official name of the religion is The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Church asks that other common monikers, such as Mormon and LDS Church, not be used, instead suggesting the shortened names “Church of Jesus Christ” or “restored Church of Jesus Christ.” Because these recommended shortened terms are highly polemical I do not use them.

Early Mormon Polygamy

The practice of polygamous marriage was one of ultimate concern for some Mormons of the mid- and late-nineteenth century.1 Joseph Smith, founding prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, received divine revelation about polygamous marriage and gradually introduced the idea to an inner circle of Church leaders in the 1830s and ‘40s, during which time Smith himself covertly married dozens of women. The teaching became more public starting in 1852 under Smith’s successor, Brigham Young. Theologically, the eternal destiny of Mormon men was linked to earthly acts of marriage and procreation, and polygamous marriage assured them heavenly exaltation of the highest order. By extension, polygamy also brought salvation for the wives who were eternally sealed to them.2 Because the practice was enacted in many different ways, with wildly varying numbers of people involved in the marriages and all manner of housing and financial arrangements, it is not possible to broadly characterize what the experience of polygamy was like or how practitioners felt about it. Diaries and other records left by Mormon women of the era attest to both positive and negative experiences with polygamous family structures. Men, too, seem to have felt conflicted: in the face of persecution, some men quickly walked away from their additional marriages while others risked extensive legal penalties in order to maintain their commitments. Even when the Church officially stopped sanctioning new polygamous marriages in 1890, a position it more forcefully reasserted in 1904, so deep was the belief in polygamy that a portion of the membership refused to abandon plural marriage.3 Some polygamous families, for instance, moved to Mexico to maintain their practice without persecution, while others broke away to form sectarian Mormon communities that continued to engage in polygamy.4

For more than a century the LDS Church downplayed its polygamous past, minimizing the role the practice played in early Mormon history and discouraging discussion of it. As historian B. Carmon Hardy noted in 2007, “A review of Mormon sermons, public statements, and art over the last hundred years gives the impression that plural marriage had little significance in the Latter-day Saint past . . . Official Mormon inattention to the subject is glaring."5 Polygamy remains an uncomfortable topic for many Church members, functioning broadly as a form of cultural shame that they would prefer to move beyond. Former Sunstone news editor Hugo Olaiz has commented, “We 21st-century Mormons cultivate the art of forgetting our polygamous past,” adding an incisive question: “When members of the media mix up Mormons with polygamy, are we upset because we perceive them to be distorting our religion, or because they are throwing a spotlight on an aspect of our religion we desperately want to forget?"6 Similarly, historian Will Bagley has written that typical members “do not like to be reminded that the doctrine remains a central element of Mormonism’s revolutionary theology and devoutly wish the world would forget about this abandoned practice."7 Yet the Church appeared to change its stance on discussing polygamy in 2014, signaled by the publication of several new articles on the LDS website exploring the history of plural marriage, and which acknowledged that Joseph Smith had somewhere between thirty and forty wives by the time of his death in 1844. The official position now acknowledges polygamy as a historical reality that was received as prophecy and was therefore divinely sanctioned for a limited period of time, but the Church sharply distinguishes itself from present day polygamy-practicing groups that claim an identity within the LDS tradition.

The official acknowledgement of the extent of Smith’s polygamy came as a surprise to many of the faithful. For some, the information was a catalyst for reconsidering the implications of religious history, and a surge of discussion took place in various online forums. But public acknowledgment did not erase the stigma or make the new information easy to digest. Historian of religion and politics Neil J. Young attempted to describe the dissonance created, writing, “the LDS Church in the twentieth century actively suppressed the history of polygamy in Mormonism’s religious identity and cultural memory. This entailed glorifying the traditional heterosexual family unit in Mormon theology and culture, coupled with negative depictions of sexuality."8 A simple position change, he suggests, could not begin to unravel the vast impact that downplaying polygamy had made over time on peoples’ conceptions of gender relations and the role of women in the Church. Furthermore, it was unclear how average Mormons would process the confirmation of information that some had previously regarded as dubious. Underscoring this situation, Carol Lynn Pearson’s 2014 survey of more than 8000 current and former Mormons found that polygamy, both as a historical reality and as a future possibility in the afterlife, continues to be “hiding in the recesses of the Mormon psyche, inflicting profound pain and fear.”9 But perhaps this also indicates the conversation is being pushed to a precipice, allowing members to begin thinking about the unthinkable in order to work toward resolution by means of a reinvented chain of memory.

Many contemporary scholars of law, religion, social history, and other fields have undertaken research on aspects of nineteenth-century polygamy. They have sought to understand it both in its original context and as a cultural institution with structural ramifications that stretch into the present. But as Pearson’s survey indicates, for the Mormon faithful there are emotional aspects of the legacy of polygamy that have not been entirely captured by these academic texts. Mormon history acts as a collective memory that binds the faithful together, so a rupture of that history is akin to a cultural trauma, requiring both cognitive and affective modes of processing in order to make sense of it in the present without simply objectifying, essentializing, or fetishizing it.10 This is where artistic forms can begin to fill a void, providing a milieu in which cultural taboos and complex responses to them are able to find expression. Furthermore, visual art that rediscovers and reimagines historical polygamy is rightly considered part of what religious studies scholar Christine L. Cusack has called “art activism.” Commenting on works created by Mormon women, Cusack writes that, “artistic expression . . . becomes a strategic method to document alternative ways of belonging, remembering, and (re)shaping religious life.”11 Contemporary art that focuses on historic polygamy is activism not only because of the interpretations it may offer about the practice, but because even the act of highlighting stories of nineteenth-century polygamous women is not unilaterally accepted as good. There are some who would say that putting any attention on the polygamous wives of Smith reifies arcane gender roles and spiritual subservience as envisioned by the prophet, and to celebrate them is to celebrate that hierarchy. They would argue that a truly modern project would keep conversations about these women dead and buried and would instead create new ideals for Mormon women.12 In contrast, others consider it an important project to unearth the stories of Smith’s wives. They say that these women should rightfully be given places of reverence as pioneers of the faith and, to some extent, sacrificial lambs. Additional perspectives that neither ignore nor revere them also emerge through the art, complicating any single understanding of the women by offering a multitude of interpretations.13 The art, therefore, is not simply a neutral reflection on history, but rather is an entry point for interrelated conversations about the roles of history and memory in understanding religion and about the role visual art can play in altering and challenging that collective memory.

- 1Most early Mormons who abided this teaching actually practiced polygyny, which is the marriage of one man to multiple women. However, prophet Joseph Smith and several other high-level leaders married many women who were themselves already married, in which case the women were engaged in polyandry. For that reason, the term “polygamy” is the most efficient term for referring to the complex array of marriages that occurred in the first half-century of the religion, and is used throughout this article.

- 2According to teachings at that time women could not achieve heavenly salvation without such a marriage, and men’s potential glory in the afterlife grew exponentially larger with each sealing. Polygamy was only ever practiced by a minority of LDS Church members, though its prevalence varied geographically. Notable treatments of the history of Mormon polygamy include: Kathryn M. Daynes, More Wives Than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840-1910 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001); Sarah Barringer Gordon, The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2002); Christine Talbot, A Foreign Kingdom: Mormons and Polygamy in American Political Culture, 1852-1890 (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013); Doing the Works of Abraham: Mormon Polygamy, Its Origin, Practice, and Demise, ed. B. Carmon Hardy (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark Company, 2007); “Plural Marriage in Kirtland and Nauvoo,” The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, October 2014, https://www.lds.org/topics/plural-marriage-in-kirtland-and-nauvoo?lang=eng.

- 3Church president Wilford Woodruff issued the Manifesto in 1890, which stated that Mormons should follow federal law regarding monogamous marriage and cohabitation. A Second Manifesto was issued in 1904, indicating that both performing and entering into polygamous marriages were excommunicable offenses. Though both declarations taught members not to engage in any new polygamous marriages, neither indicated that polygamy ceased to be an applicable concept for the afterlife.

- 4For more on the trajectory of polygamous Mormonism in Mexico see Barbara Jones Brown, “The 1910 Mexican Revolution and the Rise and Demise of Mormon Polygamy in Mexico,” in Just South of Zion: The Mormons in Mexico and its Borderlands, eds. Jason H. Dormady and Jared M. Tamez (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2015); for more on sectarian polygamous Mormons see essays in Modern Polygamy in the United States: Historical, Cultural, and Legal Issues, eds. Cardell Jacobson and Lara Burton (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

- 5B. Carmon Hardy, afterword to Doing the Works of Abraham, 390.

- 6Hugo Olaiz, “Warren Jeffs and the Mormon Art of Forgetting,” Sunstone (Sept. 2006), 68.

- 7Will Bagley, foreword to Doing the Works of Abraham, 14.

- 8Neil J. Young, “Fascinating and Happy: Mormon Women, the LDS Church, and the Politics of Sexual Conservatism,” in Devotions and Desires: Histories of Sexuality and Religion in the Twentieth-Century United States, eds. Gillian Frank, Bethany Moreton, and Heather R. White (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2018), 202-3.

- 9Carol Lynn Pearson, The Ghost of Eternal Polygamy (Walnut Creek, CA: Pivot Point Books, 2016), 7. Pearson’s study had methodological flaws, but the large number of people it included makes it useful nonetheless.

- 10See discussion of mass trauma and memory in Alison Landsberg, Engaging the Past: Mass Culture and the Production of Historical Knowledge (New York: Columbia, 2015), 7-10.

- 11Christine L. Cusack, “(Not So) Well-Behaved Women: Piety and Practice among Twenty-First-Century Mainstream Mormon Feminists,” in Postsecular Feminisms: Religion and Gender in Transnational Context, ed. Nandini Deo (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 133-34.

- 12See discussion by Joanna Brooks, “Mormon Feminism: An Introduction,” in Mormon Feminism: Essential Writings, eds. Joanna Brooks, Rachel Hunt Steenblik, and Hannah Wheelwright (Oxford: Oxford University Press: 2018), 1-23.

- 13See discussions of these various positions in: Cusack, “(Not So) Well-Behaved Women,” 134-7, and Brooks, “Mormon Feminism: An Introduction.”

Visual Art of the Mormon Experience

The LDS Church has long encouraged appreciation among its members for music, dance, theater, and literature, but visual art has been given comparatively scant attention.1 Until the latter half of the twentieth century the majority of visual art promoted in Mormon environments was functional, serving primarily to reinforce aspects of Mormon faith for believers. Artists who were Church members used a realist style to create works on themes such as Joseph Smith’s religious experiences, stories from the Book of Mormon, and the pioneer journeys to Utah Territory. Mormon convert C. C. A. Christensen (1831-1912), for instance, was commissioned to paint several temple murals, and is now most known for his series of large canvases illustrating Mormon history.2 Lee Greene Richards (1878-1950), who studied in Paris and later taught art at the University of Utah, was commissioned for portraits of Church leaders that now hang in numerous Church-owned spaces.3 At one time the Church even sponsored several men to receive formal training in France. Known as the “art missionaries,” John Hafen, Lorus Pratt, John Fairbanks, and Edwin Evans returned to paint several murals for the Salt Lake City temple.4 But the limited subject range and style of these and other Church-sanctioned artists—what some derisively label “Mormon art”—has been critiqued by many, including those who have unabashedly dismissed its artistic value. As early as 1959 a master’s student at Brigham Young University analyzed Mormon art and concluded that it was “commonplace,” “unimaginative,” and generally did “not exhibit qualities of significant aesthetic worth”; another thesis-writer more succinctly rejected Church-commissioned works as “kitsch.”5 Art critic Jane Dillenberger maintained that by the latter half of the twentieth century much of the visual art found in the Mormon public sphere was “illustrative, shallow, social-realist religious art” and therefore uninspiring.6 Yet there are also those who believe the LDS community has deeper artistic potential. Pushing in this direction, art historian Martha Bradley has called upon Mormon artists to break out of the entrenched utilitarian approach to art and use their talents to explore greater emotional depth. Only once work by Mormon artists begins to “reflect the spiritual lives of the people,” she writes, will it be able to communicate to broader audiences what this religious community “doubted and believed in, what they hoped for and were troubled by, and the ways they cared about one another.”7 Certainly, there were twentieth century Mormon artists who remained devout while also achieving widespread critical acclaim; such artists include sculptor Mahonri Young (1877-1957), painter Dean Fausett (1913-1988), and painter Joseph Paul Vorst (1897-1947). But the work that earned them praise did not overtly reflect aspects of their religious culture. In fact, further proving Bradley’s point, it appears that the majority of artists with a Mormon background who built successful careers in the twentieth century not only focused on secular subject matter but also left their faith tradition behind, while those whose work remained religiously-focused eventually faded into relative obscurity.8

- 1See discussions in: Peter Myer and Marie Myer, “New Directions in Mormon Art,” Sunstone 2 no. 1 (1977): 32-64; and Monte B. DeGraw, “A Study of Representative Examples of Art Works Fostered by the Mormon Church with an Analysis of the Aesthetic Value of these Works,” MA thesis (Brigham Young University, 1959).

- 2Jane Dillenberger, “Mormonism and American Religious Art,” Sunstone 3 (May/June 1978), 13-7.

- 3Delbert Waddoups Smedley, “An Investigation of Influences on Representative Examples of Mormon Art,” MA thesis (University of Southern California, 1939).

- 4Martha Sonntag Bradley, “Mormon Art: Untapped Power for Good,” This People 13 (1992): 20-26; Martha Elizabeth Bradley and Lowell M. Durham, Jr. “John Hafen and the Art Missionaries,” Journal of Mormon History 12 (1985): 91-105. The names of the art missionaries differ in various publications.

- 5DeGraw, “A Study of Representative Examples,” 36, 65; Lori Schlinker, “Kitsch in the Visual Arts and Advertisement in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,” MA thesis (Brigham Young University, 1971). See also Paul L. Anderson, “Mormon Architecture and Visual Arts,” in The Oxford Handbook of Mormonism, eds. Terryl L. Givens and Philip L. Barlow (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 470-84. Anderson attributes this trend of functional art to the “disapproval of excessive display” brought into the tradition early on by its austerity-minded Protestant converts.

- 6Dillenberger, “Mormonism and American Religious Art,” 17.

- 7Bradley, “Mormon Art,” 26; see also Myer and Myer, “New Directions in Mormon Art.” Bradley now uses the surname Bradley-Evans.

- 8For more on this, see: The Mormon Artists Group, The Glen & Marcia Nelson Collection of Mormon Art, 2nd ed., (iBooks, 2015); Smedley, “An Investigation”; Myer and Myer, “New Directions in Mormon Art.”

For female artists, the desire to balance art and faith has been more fraught, because the decision to place faith first has usually meant a lifestyle dominated by the work of motherhood and homemaking without much space for artistic endeavors. Though there is less of it to assess, Mormon women’s art of the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries demonstrates greater variety than men’s both in subject matter and style. This is surely related to the comparatively fragmentary way that their creative work developed, in that they were less likely to receive formal training or earn money for their work, and that almost none received Church support such as commissions.1 Even one of the most highly regarded female Mormon artists, Minerva Teichert (1888-1976), has received little attention outside of Mormon circles. The subject matter of much of her work fell within acceptable Church frameworks, which is part of the reason it did not appeal to secular audiences, yet Teichert pushed the boundaries by reimagining Book of Mormon stories with women included, and showing active female figures in her depictions of pioneer life (Fig. 1).2 Notably, this makes her work the clearest ideological precursor to the contemporary artists who are exploring and reenvisioning polygamy. Polygamy itself is not, however, a topic Teichert ever depicted.

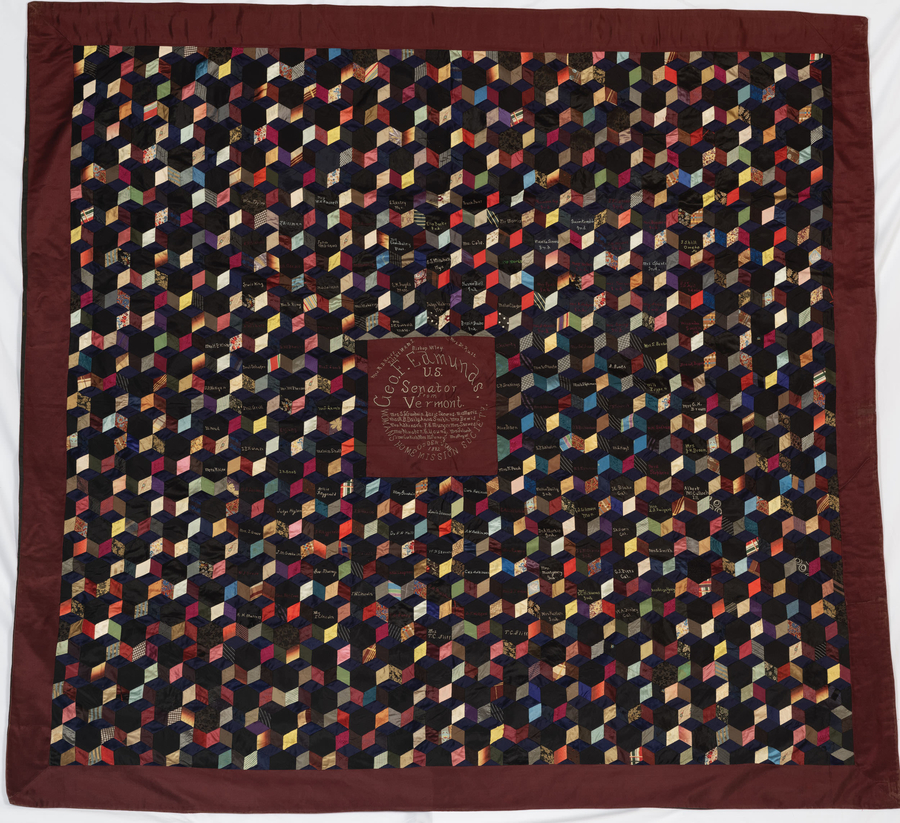

Although many aspects of the early Mormon experience have been meticulously documented in murals and other Church-sanctioned visual art, it is surprisingly difficult to find LDS-created artistic representations of polygamy from the era when it was an official Church teaching. Just as discussion of polygamy was suppressed within the Church, art representing it appears to have been tacitly discouraged, leaving a concomitant hole in the visual record. Instead, the primary visual records of polygamy from the nineteenth century are family portrait photographs, whose purpose was commemorative documentation and which are relatively few in number.3 Far more plentiful from that era are satirical cartoons and illustrations intended to embellish the content of anti-Mormon articles, which were regularly published in both national magazines and local newspapers.4 One can also find advertisement art that drew on salacious and sexualized notions of polygamy, such as for the patent medicine “Mormon Elder’s Damiana Wafers,” which promised users increased virility. Nestled among mass-produced images such as these are a few random individual art pieces, but these, too, tended to offer a critical message about polygamy. One example is the Ogden (Utah) Methodist Women’s Association anti-polygamy quilt, which was created in the early 1880s as an affirmation of the Edmunds Act (Fig. 2).5 The decorative quilt of geometric shapes in dark colors included stitched names of people from across the country who donated money to support its creation and its message. The work was intended as a public, non-verbal political statement against polygamous marriage, and its makers hoped it would be displayed prominently by the Republican senator who had introduced the anti-polygamy bill, George Edmunds.6

- 1Erika Doss, “’I Must Paint’: Women Artists of the Rocky Mountain Region,” in Independent Spirits: Women Painters of the American West, 1890-1945, ed. Patricia Trenton (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995), 208-41. This remains an area where more study and collection is needed.

- 2Marian Wardle, Minerva Teichert: Pageants in Paint, exhibition catalogue (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 2007); Rich in Story, Great in Faith: The Art of Minerva Kohlhepp Teichert, exhibition catalog (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1988); Doss, “‘I Must Paint,’” 237-40.

- 3On a related theme, Mary Campbell has explored how turn of the century photographs were used to reshape the image of Mormons, most especially allowing them to shed public impressions of polygamy. Mary Campbell, Charles Ellis Johnson and the Erotic Mormon Image (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016).

- 4W. Paul Reeve has examined a subset of political cartoons that relate to racialized depictions of polygamy. Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015); see also: Gary L. Bunker and Davis Bitton, The Mormon Graphic Image, 1834-1914: Cartoons, Caricatures, and Illustrations (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1983); Gail Farr Casterline, “‘In the Toils’ or ‘Onward for Zion’: Images of the Mormon Woman, 1852-1890,” MA thesis (Utah State University, 1974); and J. Spencer Fluhman, “A Peculiar People”: Anti-Mormonism and the Making of Religion in Nineteenth-Century America (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2012).

- 5Numerous pieces of legislation sought to eliminate polygamy, but essentially functioned to incrementally delimit and prosecute it. The federal Edmunds Act (1882) increased the types of punishments for polygamy, such as being stripped of the right to vote, serve on a jury, and hold public office, as well as enumerating potential fines and jail sentences.

- 6The Methodist women’s organization went by several slightly variant names. See Mary Bywater Cross, “The Anti-Polygamy Quilt by The Ogden Methodist Quilting Bee,” Uncoverings: The Research Papers of the American Quilt Study Group vol. 24 (2003): 17-48.

In the late-twentieth and early-twenty-first centuries, the complexity of Mormon polygamy has begun to be addressed through visual means. Finally, artists—primarily women who come from an LDS background—are taking up the subject anew and exploring it through contemporary lenses of marital relationships, sexuality, and women’s self-determination. Leslie O. Peterson, Katie West Payne, and Angela Ellsworth, the three artists discussed herein, have each produced at least one major series of works dealing with the history of polygamy. Though stylistically distinct from one another, their work challenges viewers to consider both the experience of polygamy and its long-term impact.1 Their work may also serve as launching points for new patterns of thought and consciousness among the faithful because they use visual rather than rhetorical means to disrupt the traditional narrative, which means they speak to audiences on multiple levels. By extension, more widespread public exposure to these women’s art inevitably broadens contemporary discussions about the nature of polygamy and its social impacts.

- 1In addition to these three, there are other contemporary artists whose work has reflected on Mormon women’s history and, in greater or lesser degrees, polygamy. These include Valerie Atkisson, Rachel Farmer, Page Turner, Kelly McAfee, and Lane Twitchell. They are not included in the present discussion because their work is ideologically distinct in significant ways.

Representing Mormon Feminism

Leslie O. Peterson did not particularly consider herself a Mormon feminist, but in 2014 her artistic impulses unwittingly pushed her into the movement.1 Peterson, a lifelong Mormon who grew up in California, first began taking art classes with her son-in-law in 2012. Discovering that she had both talent and a passion for painting, Peterson experimented with various subjects including nature scenes, still lives, and portraits, and she started a blog where she regularly posted both completed and in-progress works. In the autumn of 2014 Peterson learned of the Church’s acknowledgment of Joseph Smith’s extensive polygamy. “It really, really upset me,” she later said, “I had known about polygamy years ago, but the Church made me believe that . . . maybe it hadn’t happened.”2 Her realization about the extent of the founding prophet’s involvement, with more than thirty wives, disturbed her deeply, and the fact that the Church had always known about it caused her to wonder what else the institution might be hiding.3 Peterson turned her feelings of shock and betrayal into art. Her first painting on the subject, Joseph and Emma and his Invisible Wives, features the faceless heads of nearly forty women surrounding the fully detailed busts of Joseph and Emma Smith. Some of the heads wear bonnets, and Peterson indicates age by both hairstyle and hair color. Joseph stares at the viewer while Emma looks slightly downward, but neither face has a recognizable expression. After Peterson posted the image online it went viral; Peterson had unknowingly stepped into the new, public conversation bubbling up about the history of Mormon polygamy. But Peterson’s rendition of the women also reflected her limited understanding: “I realized I didn’t know anything about them,” she recalled, “These women had become ghosts in our history, and we don’t teach or talk about their lives.”4

Feeling compelled to recover something of the lives of these Mormon foremothers, Peterson began to research. Foremost among her sources was the podcast Year of Polygamy, which focuses on the history of polygamy and the stories of Smith’s many wives, as well as the book it was originally based upon, Todd Compton’s In Sacred Loneliness.5 At over eight hundred pages, Compton’s book draws on an array of primary source documents to provide biographical sketches of thirty-three of Smith’s wives. Peterson used this material to create a small watercolor portrait of each woman. She worked from photographs taken when the women were in their older years, yet Peterson aimed to portray each wife as young and vibrant. Up until she began this series, her painting style had been primarily realist, but her “Forgotten Wives” series is deliberately naïve and stylized. Each piece is a bust-length painting in which the women have long necks and disproportionately large heads (Figs. 3 and 4). Many have a slight, closed-lipped smile and look straight at the viewer whereas others, such as the portrait of Helen Mar Kimball, have a sad or wayward look; the tears in Kimball’s eyes are intended to represent sorrow at being married to Smith at age 14. Through tiny details like this one, Peterson infused the paintings with references to each woman’s actual life, capturing an aspect of who she was beyond the vague identity of polygamous wife of the prophet. Her final method for acknowledging their individuality was to put each woman’s name on her portrait—in some cases her maiden name, and in others a married name that she used either before or after her marriage to Smith. Peterson herself describes the pieces as “rough,” adding with a laugh that she would have spent far more time on them if she had known how much attention they were going to receive.6 The series of thirty-four portraits, completed in early 2015, was ultimately exhibited at several different galleries in Utah and received favorable press coverage in publications including the New York Times and Huffington Post.7 Peterson also produced a composite poster of the images that became a popular item sold online.8 Critical response focused on the political significance of Peterson’s paintings. As art historian Nancy Ross told the New York Times, by recognizing the individuals, this series stands in contrast with so much of Mormon art in which men are portrayed in detail but “Mormon pioneer women are nameless and faceless.”9

- 1A Mormon feminist is one who identifies both with feminist aims of equality of the sexes and with the Mormon faith. The contemporary Mormon feminist movement dates to the 1970s, but earlier waves align with nineteenth-century developments like the leadership of Eliza Snow and the original publication of the Women’s Exponent. See discussion in Brooks, “Mormon Feminism: An Introduction.”

- 2Leslie O. Peterson, “The Art of Mormon Feminism,” Video recording of talk at Salt Lake Oasis, 32:52, December 11, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sixbimoHIeo ; Leslie’s Art Blog, October 2014, http://leslieopeterson.blogspot.com.

- 3Leslie O. Peterson, telephone conversation with author, October 29, 2018.

- 4Leslie O. Peterson, “Celebrating the Forgotten Wives of Joseph Smith,” Video, 5:55, June 14, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h0QxpeNg9ZA. There continue to be discrepancies in the research regarding the precise number and identity of Smith’s wives, hence not all books nor artistic representations agree with each other.

- 5The Year of Polygamy, hosted by Lindsay Hansen-Park, began in 2014 as a weekly series for the Feminist Mormon Housewives Podcast, and its popularity caused it to continue into the present and expand beyond this original focus; Todd Compton, In Sacred Loneliness: The Plural Wives of Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Press, 1996).

- 6Peterson, conversation with author.

- 7Jennifer Dobner, “Mormon Leader’s 34 Wives Inspire a Utah Artist,” New York Times, August 18, 2015; Carol Kuruvilla, “Joseph Smith’s Many Wives Come to Life in Mormon Artist’s Portraits,” Huffington Post, August 28, 2015, https://www.huffpost.com/entry/joseph-smith-mormon-wives-paintings_n_55df2b1fe4b08dc094869a8c.

- 8Her poster is reminiscent of the popular late-nineteenth century postcard that featured small photographs of Brigham Young and twenty-one of his wives.

- 9Dobner, “Mormon Leader’s 34 Wives.”

Peterson’s art about polygamy is primarily retrospective. It deals with recovering lost history, rather than struggling with what an afterlife populated with polygamous families might mean. Her intention was to learn the women’s stories and overcome her anger at the Church for what she saw as complicity in an extensive lie. But her work also challenges the collective chain of memory because she puts the faces of often clearly pained plural wives front and center. Furthermore, because she was interested in unpacking the unpleasant past through visual means, hers was also a new voice in the world of Mormon feminism. As Cusack notes, Peterson had joined the ranks of those women who had, for decades, been “challenging the erasure of women’s experience in Church history and negotiating embedded tensions around gender in Mormon culture, doctrine, and practice.”1 In trying to talk about the new realizations with her Mormon peers, Peterson put attention on a subject that was already taboo, and she found that initiating such conversations made people regard her as “edgy, or anti-Mormon."42 This is because, as one writer described it, “Peterson [was] not merely painting; she [was] testing the boundaries and politics of Mormon authoritative discourse.”2

Peterson unilaterally considers polygamy to have been a horrible way of life. “Some say it was a necessary sacrifice,” she explained in conversation with the author, “or that it was necessary to populate Utah, or that it showed our strength as a people.” But she disagrees. “These were great women in spite of polygamy, not because of it!”44 By recognizing their contributions as individuals, not just as wives, her art pushes back against what she perceives as the erasure of women from the history of the faith, and she suggests women can be significant in the present for their individual qualities rather than for their marriages. What is most significant about Peterson’s work was not that she offered particularly new ideas to Mormon feminism, but rather that she presented a different medium for ideological expression. Furthermore, the exposure her work received amplified discussion of the issue far beyond a Mormon audience.

Six months after her “Forgotten Wives” series was complete, Peterson returned to the subject of polygamy with Sisters in Zion. This family portrait, created in the same style, shows five of Smith’s wives sitting together in a formal pose with a portrait of Joseph hanging in the background. Unsmiling, they all look directly at the viewer. Subsequent pieces completed in 2015 and 2016 included brightly colored acrylic portraits of individual Smith wives with more visual context about their lives. In the portrait bearing her name, Fanny Alger, for instance, stands in a field, surrounded by flowers as symbols of her life and relevance to Mormon history. Flanked by portraits of husbands Joseph Smith and Brigham Young, the subject of Zina Huntington Jacobs Young Smith sits holding a picture of her beloved original husband, Henry. And, though her eyes are covered with a large cowboy hat that references the disguise she wore when marrying Smith, Louisa in 5 Tiny Graves wears a confident smile.3 Most of these more recent pieces were made on commission for collectors, but eventually polygamy fell out of Peterson’s creative repertoire. As she stated in late 2018, “I processed it and moved on,” adding that, as a part of moving on, she had also left the Church. “I guess you can’t call me a Mormon feminist anymore.”4

- 1Cusack, “(Not So) Well-Behaved Women,” 133.

- 42Peterson, conversation with author.

- 2Sonja Farnsworth, “The Art of Feminism: Forgotten Wives Remembered,” Sunstone 182 (Fall 2016), 31.

- 44Peterson, conversation with author.

- 3The title of this piece refers to the fact that all five of her children, who were fathered by her second husband Brigham Young, died in infancy.

- 4Peterson, conversation with author. Peterson sent an official letter of resignation to the Church in September 2018.

Symbols of Pain

In 2015, artist Katie West Payne was completing an MFA at Brigham Young University when she simultaneously took two classes that pushed her in new directions: drawing, and Mormon women’s history.1 As a sculptor who worked primarily in textiles, the drawing class required Payne to express herself in a different medium. Meanwhile, the history class caused her to think more seriously about Joseph Smith’s polygamous past, which she had been aware of but now began to struggle with. Although she knew that in some cases polygamy allowed women access to education and other independent pursuits, in general she regarded it as a negative part of the Church’s past. Moreover, she was troubled by the absence of these women from public history. “The Church only talks about Emma,” she lamented; if Smith saw fit to marry so many additional women, why were their stories not common knowledge? Payne’s husband gave her what she at first regarded as a “stupid gift” that would exacerbate her anguish: Compton’s book In Sacred Loneliness. But as she read, the women’s stories came alive for her, and their history blended with an assignment she had received in her drawing class. The resulting mixed-media series, “Plural Wives of Joseph Smith,” was exhibited in Provo later that year and was subsequently purchased for the permanent collection of the LDS Church History Museum.2

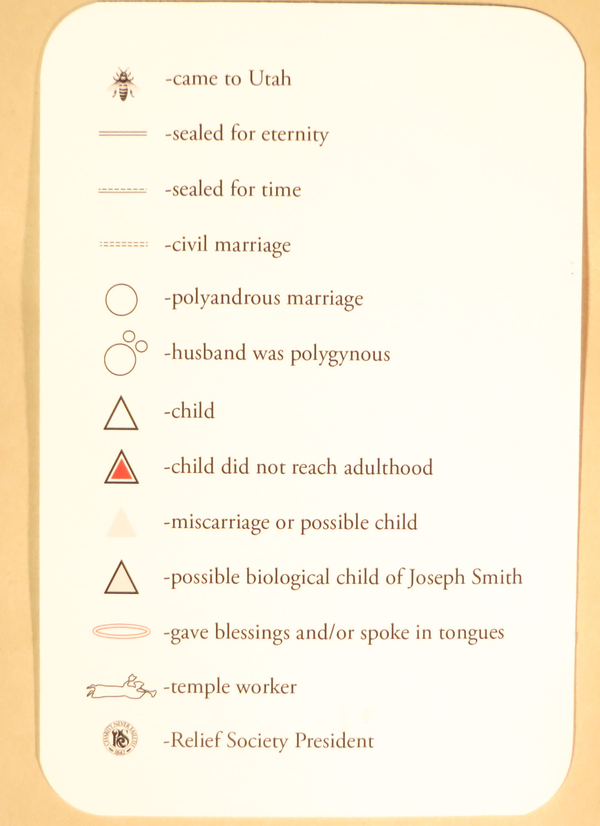

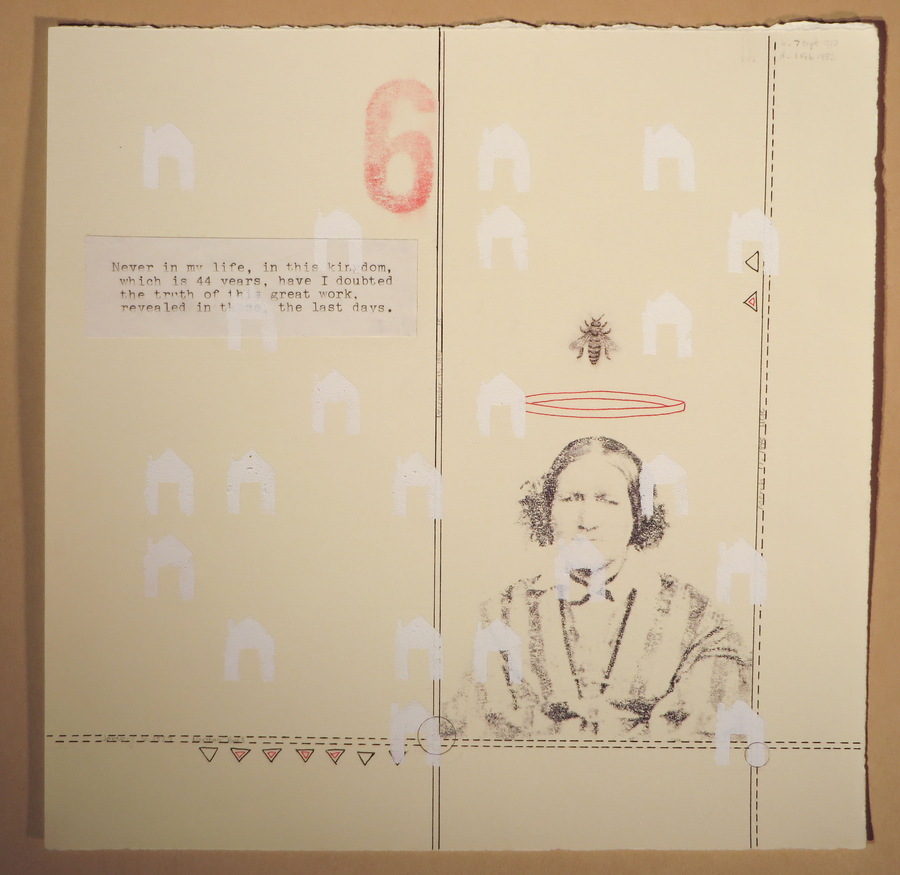

Pulling details from Compton’s book, many of which she turned into an intricate symbol system, Payne’s series sequentially represents each of Smith’s wives from numbers two to thirty-four and ends with his first wife, Emma. The works are collage on paper that mix fine-lined drawing, photo transfer, typed text, ink, torn paper, stamping, and numbers. Some of the pieces have identifiable maps and photographic images while others are closer to linear abstractions, and many have cut-out sections that enable the viewer to see a second image placed behind it. Despite the multitude of techniques employed, the pieces have an overall stark appearance because most are dominated by the pale hue of blank, untouched paper.

The series is intended to begin with a key card that gallery viewers can carry with them as a guide, on which thirteen specific symbols represent events in the women’s lives (Fig. 5). Many of the works include additional symbols specific to the individuals; Payne describes every mark on the page as an intentional reference to an aspect of that woman’s personal story. The bits of text, which are snippets from diaries and letters originally reproduced in Compton’s book, allow a layer of additional insight. For instance, Payne’s piece representing wife number six, Presendia Lathrop Huntington, includes not only symbols for marriages, children, and temple work, but also numerous ink stamps of tiny houses (Fig. 6). As Payne explained, the houses represent the fact that, as a wife with relatively low status, this woman was required to move many times; Compton suggests the number of relocations may have exceeded twenty. He elaborates, “These continual moves must have been a great strain for Presendia, who loved the security of a good home.”3

- 1Katie West Payne is distinct from Katie Payne, another Mormon artist who specializes in illustration.

- 2Katie West Payne, telephone conversation with author, November 15, 2018. Payne completed only a small portion of the extensive series for her drawing class. The consequence of its purchase by the museum is that its public display was short-lived.

- 3Payne, conversation with author; Compton, In Sacred Loneliness, 137. Wife number six in Compton’s book is Presendia Lathrop Huntington, who was polygamously married to both Joseph Smith and Heber Kimball in addition to her first husband Norman Buell.

In a similar attempt to reveal the darker emotions in the women’s lives, through the window of Payne’s piece representing wife number twenty-nine, Rhoda Richards, a bittersweet passage appears on the back panel:

“In my young days I buried my first and only love, and true to that affiance, I have passed companionless through life; but am sure of having my proper place and standing in the resurrection, having been sealed to the prophet Joseph Smith, according to the celestial law, by his own request, under the inspiration of divine revelation.”1

Richards (1784-1879) was raised in the Boston area and followed several family members into the Latter-day Saint faith in the 1830s. In her late twenties she fell deeply in love and became engaged to Ebenezer Damon, but he died of sudden illness before they could marry. Richards essentially spent the next seven decades living a spinster’s life, being shuttled about to live with various family members and battling frequent health issues. And yet, along the way, she secretly became a polygamous wife to both Joseph Smith (1843), and to her cousin Brigham Young (1845). These unions are what Compton has called “dynastic matrimony,” in that they were not romantic, they were not made public, and they appear to have served as a method for linking specific families.2 In Payne’s piece, Richards is no longer a secret wife of the prophet. Symbols represent her two marriages and her extensive travels, and the front panel includes drawings of medicinal bottles that reference her ongoing health issues. But it is the section of text seen through the window that lays bare Richards’ private assessment of her own life, happily anticipating her eternal future while in the same breath conveying sadness at lost love. In these examples and others, the textual excerpts and the visuals work together to flesh out the forgotten life stories of Smith’s many wives.

What is most notable about Payne’s piece is its intellectual complexity. Even using the key card, an average viewer would not be able to understand all of the symbolism without additional explanation. Payne is comfortable with the fact that many people will miss some of her work’s significance; rather than feeding them answers, she hopes the pieces will act as a catalyst that pushes viewers to seek out the deeper stories. As with Peterson, the series was a means for Payne to process her own discomfort with the history of polygamy, and it was an emotional project in which she deliberately focused on damage done to the women’s lives. For instance, little is known about wife number nineteen, Flora Ann Woodworth, a teenage bride of the prophet. To represent her, Payne drew freely-flowing locks of hair. This referred to a time when Flora was so isolated by illness that by the time a sister wife was finally able to care for her, Flora’s “heavy raven locks were so matted together that it took [her] hours to comb them out.”3 Payne recalled this story with a crack in her voice. It was by consciously choosing to represent incidents that were painful to think about that she was able to sort through her feelings about polygamy’s effects on the lives of her Mormon ancestors and their descendants.

Payne attempted to humanize each woman by recounting her personal history. Yet because of the way the series is structured, the pieces are dependent upon one another, and the women remain tied together as part of a single narrative; they are trapped in a patriarchal structure even as their lives are exhumed. Furthermore, because most are only identified by a number designating her spot in the order of Smith matrimonies, their anonymity is perpetuated.4 If viewers feel discomfort from this or any other aspects of the series, the artist would consider it a success, because it would mean awareness about the past is being reinvigorated. Most importantly, she hopes viewers would see the folly in dismissing polygamy as something old and distant that has no bearing on Mormon women today. As Payne herself says in an inadvertent nod to the concept of the chain of memory, “We can only begin to move forward if we remember our heritage.”5

- 1The original source of this quote, which was reproduced in Compton, In Sacred Loneliness, 568-9, appears to be a letter that Richards wrote a year prior to her death.

- 2Compton, In Sacred Loneliness, 558-76.

- 3Helen Mar, as quoted in Compton, In Sacred Loneliness, 393.

- 4There are a few exceptions in which the woman’s name is embedded in the collage, but these are often difficult to read.

- 5Payne, conversation with author.

Dichotomies of Polygamy

The artist with the most extensive body of work reflecting on polygamy is Angela Ellsworth, who was raised Mormon in Salt Lake City and later left the Church. Ellsworth, an art professor at Arizona State University whose work has been shown in venues around the world, has earned critical acclaim in painting and sculpture as well as performance art.1 Ellsworth first began exploring polygamy after hearing uncomfortable stories about her ancestors, one of whom was Eliza R. Snow, a wife of Joseph Smith who later rose to prominence within the Church.2 Smith’s first wife, Emma, was outspoken in her opposition to polygamy, and for that reason his extensive wife-taking was generally kept hidden from her.3 The tale that captured Ellsworth’s attention was one in which a newly enlightened Emma pushed pregnant Eliza down the stairs, causing her to miscarry.4 Ellsworth wrote that learning about this story “evoked my interest in not only my own lineage of polygamy (which existed on both sides of my family), but more specifically in women’s lack of voice.”5

Ellsworth’s 1993 MFA thesis, “The Pious or The Perverse? Two Women Within the Construct of Mormon Polygamy,” is thirty pages of text accompanied by a series of related art works. The text has a poetic quality to it, vacillating between a discussion of historical polygamy, which she describes as “institutionalized slavery,” and excerpts from different versions of the Emma and Eliza story.6 She distinguishes the life trajectories of the two women. After Smith’s death, Emma became estranged from the Church. She remarried outside of the faith, and eventually joined her son Joseph as a member of the non-polygamous Reorganized Church of Latter Day Saints. Eliza not only stayed in the polygamous life but became a prominent leader, serving as president of the women’s Relief Society from 1866-87 and penning a famous poem (later set to music) that speaks of the Heavenly Mother, the counterpart to the Heavenly Father in Mormon cosmology. Eliza’s published works, including diaries and poetry, document social history within the Church, but because she elided her personal feelings as she recounted these events, ultimately Eliza the person is just as absent from the historical record as Emma, who left no writings.7 As Ellsworth put it, Eliza “was regarded as a saint, precisely because she had no voice. Because Eliza’s personal narrative was silenced, she was highly respected.”8 Exploring the women’s polygamous situation through both writing and artwork allowed Ellsworth to “address the different ways in which restriction of female sexuality functions both physically and psychologically.”9

- 1Biographical information is compiled from: Seeing is Believing: Rebecca Campbell and Angela Ellsworth, Phoenix Art Museum (2010), exhibition catalog; Dress Matters: Clothing as Metaphor, Tucson Museum of Art (2017), exhibition catalog; and the artist’s website, aellsworth.com.

- 2Eliza Roxcy Snow, a poet who joined the Church in 1835, was sealed to Smith in 1842. Snow was highly respected for her leadership and today many consider her the prototypical Mormon feminist. Snow’s role and prominence within Church culture, however, is not the subject of Ellsworth’s art.

- 3Merina Smith, Revelation, Resistance, and Mormon Polygamy: The Introduction and Implementation of the Principle, 1830-1853 (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2013), esp. chapters 3 & 4; see also Linda King Newell and Valeen Tippetts Avery, Mormon Enigma: Emma Hale Smith (New York: Doubleday, 1984).

- 4Ellsworth acknowledges that this story is akin to an LDS legend, in that it has been recounted in numerous publications with details that change, and its historical basis is entirely uncertain. See an analysis in: Brian C. Hales, “Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and the Reported Incident on the Stairs,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2009), 63–75.

- 5Angela Ellsworth, “The Pious or The Perverse? Two Women Within the Construct of Mormon Polygamy,” MFA thesis (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey: 1993), 28.

- 6Ibid, 15.

- 7Ibid, 4-7.

- 8Ibid, 4.

- 9Ibid, 29.

The artwork accompanying the written thesis—all portraits—includes two charcoal drawings and eight large oil paintings with broad brush strokes. Each piece features one or more women, most without much facial expression, in physical bondage. Straps with thick buckles constrict the women’s flesh, wrapping multiple times around bodies or faces and in some cases blocking vision and speech. Yet curiously, in many of the pieces, a degree of independent agency is suggested. This is conveyed visually in pieces such as She Zips, She Sews, and She Buckles, where the women’s free hands are holding the ends of their own binding straps, and it is indicated through the titles, such as the charcoal drawings Self-Taut I and Self-Taut II, each a close-up of a bound head. Ellsworth’s pieces represent polygamy as a highly restrictive existence, but they add the discomfiting idea that women were colluding agents in this structure of marriage, family, and sexuality. Only one piece in the collection appears different—and at least partially hopeful—in tone. In the painting Trojan Women, two female figures sit side by side, their feet attached to large blocks with casters on the bottom (Fig. 7). One woman is holding the thread that ties her foot to the block, and it is unclear whether she is sewing herself in or pulling herself out of it. In the context of the other pieces, it would make sense that she is binding herself; however, assuming that the painting intends to represent Emma and Eliza as the thesis text does, this is surely Emma, and she is freeing herself in order to leave the polygamous life. The second woman, presumably Eliza, has collapsed on the couch in apparent exhaustion, making no move to untie the blocks from her feet.

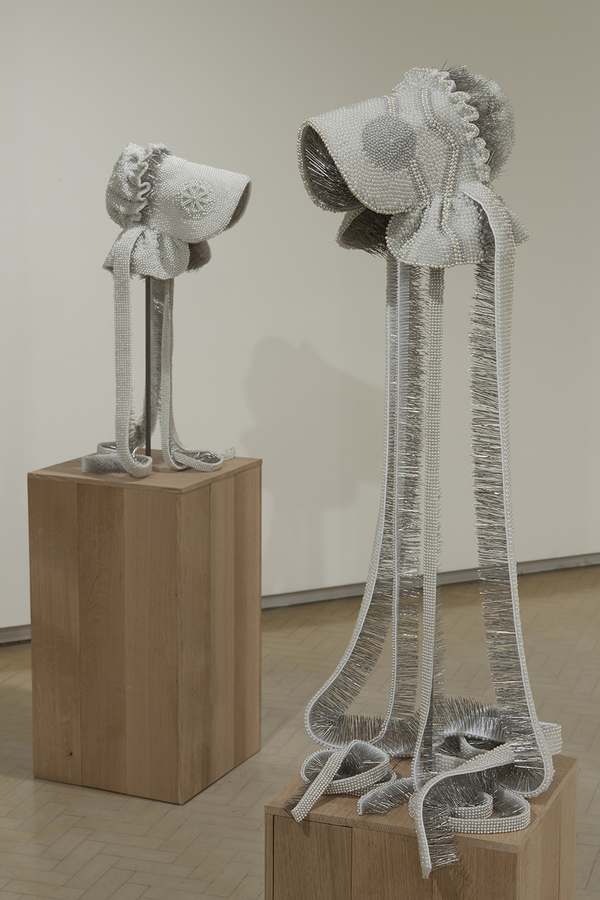

Ellsworth returned to this subject fifteen years later with the start of her ongoing “Plural Wife Project,” which involves components of sculpture, performance, and video. In this work she has continued to explore dichotomous tensions about polygamy through themes of embrace and rejection, freedom and control, and security and chaos. Her sub-series titled “Seer Bonnets: A Continuing Offense,” first shown at the 2010 Biennale of Sydney, was a nine-piece set of bonnet sculptures representing the nine wives of Mormon Church president Lorenzo Snow, a younger brother of Eliza (Fig. 8). Ellsworth described the bonnets as “beautiful to see at first glance...[but] actually quite dangerous and unwearable.”1 The prairie-style bonnets have expansive brims and long straps, stylistically similar to what would have been worn by Mormon pioneer women in the nineteenth century.2 Into a cotton shell Ellsworth tightly packed tens of thousands of corsage pins with the sharp ends pointing inward, creating an ensnaring headpiece. While the pins’ gray and white pearl tops create delicate, subtle designs on the exterior, each bonnet has slightly oversized proportions, just enough to be a little bit disturbing to the viewer. In contrast with the original lightweight bonnets after which they are modeled it is evident that each of Ellsworth’s sculptures is both heavy and inflexible. In public displays every bonnet is positioned to stand straight and tall, evocative of a person, and viewers may have to study the piece for a moment before recognizing its sharp internal structure.

- 1Angela Ellsworth, “Up Close with...Angela Ellsworth,” Video, 4:33, June 17, 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1bkSzV8fiQ.

- 2The bonnet as a material object is worthy of its own intellectual interrogation. Beyond the LDS context, where it is strongly associated with pioneer women and also symbolic of female submission both past and present, a comparative look at the bonnet’s relevance for religious groups including Puritans, Quakers, and Mennonites is ripe for exploration. An additional angle that should not be overlooked is the use of bonnets to communicate racialized notions of beauty and class, particularly in the nineteenth century.

The contrast of the exterior and interior of the bonnets was one indication of the artist’s revised perspective on polygamy, in which it was no longer represented simply as bondage. This revised perspective reverberates through other aspects of her series. For instance, as Ellsworth has explained, the first half of the “Seer Bonnets” title “suggests a new tool of translation.”1 In this, she refers to Joseph Smith’s discovery of buried plates of text and the special instruments used for translating them, one of which was called a “seer stone.” His work resulted in the Book of Mormon and the birth of a new faith. Ellsworth implies that the bonnets are, similarly, tools that give women heightened understanding as well as the potential to envision entirely new possibilities. The subtitle, “A Continuing Offense,” refers to federal charges filed against Lorenzo Snow. In 1886 Snow was convicted for cohabitation with multiple women who lived as his wives, in violation of the Edmunds Act. The court considered whether Snow should be charged and tried separately for each woman involved but determined that it was more appropriate to consider his actions “one continuous offence.”2

These title elements indicate that Ellsworth has moved away from seeing polygamy as primarily a constricting and enslaving existence, as she portrayed it in her earlier work. The bonnets no longer symbolize submission, instead acting as a kind of superpower—seer bonnets—to to be activated by women themselves. Here, she presents polygamy as a radical reconstruction of domestic life: a social setting with intrinsic positive potential for women to demonstrate both mutual support and personal strength, without any reference to husbands. This is confirmed by a 2012 artist’s statement, in which she described her vision for the larger project: “Focusing on sister-wives as a point of departure for discussing contemporary issues around nonheteronormative relationships, I reimagine a community of women with their own visionary and revelatory powers as they pioneer new personal histories.”3 One art critic saw contemporary parallels in the series, and pushed its implications even further by surmising, “Ellsworth likens recent polygamy prosecutions of FLDS members to the continuing stigmatization of same-sex marriage.”4 Whether or not that was among Ellsworth’s intended messages, the striking nature of her work does suggest its potential to prompt new levels of consciousness. Her newer work in particular challenges viewers to reconsider their own assumptions about Mormon polygamy, both past and present, and to recognize the social determinants at work in our conceptions of normalcy and deviance in mainstream American family structures.

In the ensuing years Ellsworth has continued sculpting bonnets in an effort to represent each of Smith’s wives, and she has also staged and filmed various performance pieces centered on polygamous wives demonstrating independent agency. Though she has turned the narrative of Mormon polygamy in a new direction, it is possible that the original stories continue to haunt her. Evidence of this is suggested by an image included in the catalogue for a 2010-11 exhibit at the Phoenix Art Museum. The small drawing, identified only as an untitled “sketch courtesy of the artist,” consists of two pieces of tracing paper taped one atop the other, both positioned above a drawing of a staircase. The front piece of paper shows a woman standing with a sullen face; the fainter image coming through from the sheet behind shows a woman reaching around her, bent slightly forward, and looking down the stairs. Certainly, this is a return to the legend of Emma and Eliza. Despite the context of a reimagined polygamous world where women control their own fate, Ellsworth has not been able to re-envision this one tragic story, allowing it to stand as a stark reminder of the pain polygamy introduced into many women’s lives by setting them against each other and fomenting emotions including jealousy, resentment, and self-doubt.

- 1Angela Ellsworth, “Artist’s Statement: The Plural Wife Project,” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 33.1 (2012), 48. Italics in original.

- 2In re Snow, 120 U.S. 274, 7 S. Ct. 556, 30 L. Ed. 658, 1887 U.S. LEXIS 1974 (Feb. 7, 1887). Proving multiple marriages was difficult for law enforcement agencies. For that reason the 1882 Edmunds Act made cohabitation illegal, as that offense was much easier to identify and prosecute.

- 3Ellsworth, “Artist’s Statement,” 48.

- 4Kathleen Vanesian, “Angela Ellsworth: Pinning Down the Past,” Fiberarts 37.4 (2010/11), 27.

Emma: The Starting Point for Reinvented Memory

All of these artists take the history of Smith’s wives as a central project, paying homage to the struggles they endured. Peterson has done this by highlighting aspects of the women’s lives unrelated to their marriages; Payne has done this by juxtaposing their achievements with their inner thoughts; and Ellsworth has done this by meditating on themes of bondage and freedom. Although these artists have engaged with the history of polygamy in different stylistic and ideological ways, it is notable that each focused particular attention on Emma Smith. This is because she is a figure of contradiction and is therefore the first puzzle to work through. Emma, who was both the first wife of the prophet and a woman who openly opposed polygamy, has become a touchstone of the historical practice for modern interlocuters, serving as both hero and anti-hero. All of the artists explore her resistance and attempt to grapple with her feelings. It is because of her conflicting positions on polygamy—her clear, vocal opposition to its practice within the Church, and her subsequent rigid denial that the practice ever existed at all—that Emma is the most troubling historical figure for these artists, and that fact is evident in the wildly different ways they render her.

Leslie O. Peterson portrayed Emma at least half a dozen times, always emphasizing her independence both from Smith and from the other wives. “She was one of our first feminists,” Peterson wrote under a sketch posted to her blog.1 In Peterson’s “Forgotten Wives” series Emma is beautiful, with porcelain skin, dark hair, and red lips. In a later version, Emma is adorned in a tiara and cape, her hair hanging loose, and although she looks like a young woman her surname is that of the man she married after Smith’s death. In a portrait that Peterson based on a photograph from the last decade of Emma’s life, she is shown with her adult son Joseph, and the rich colors—purple, gold, and burnt orange—along with her facial expression, suggest an inner serenity. She is beautiful, and she is interesting—these are the personal traits she carries with her. Through Peterson, a viewer sees Emma as a woman with her own identity, worth knowing for her own sake rather than as an extension of the prophet or in relation to the other wives.

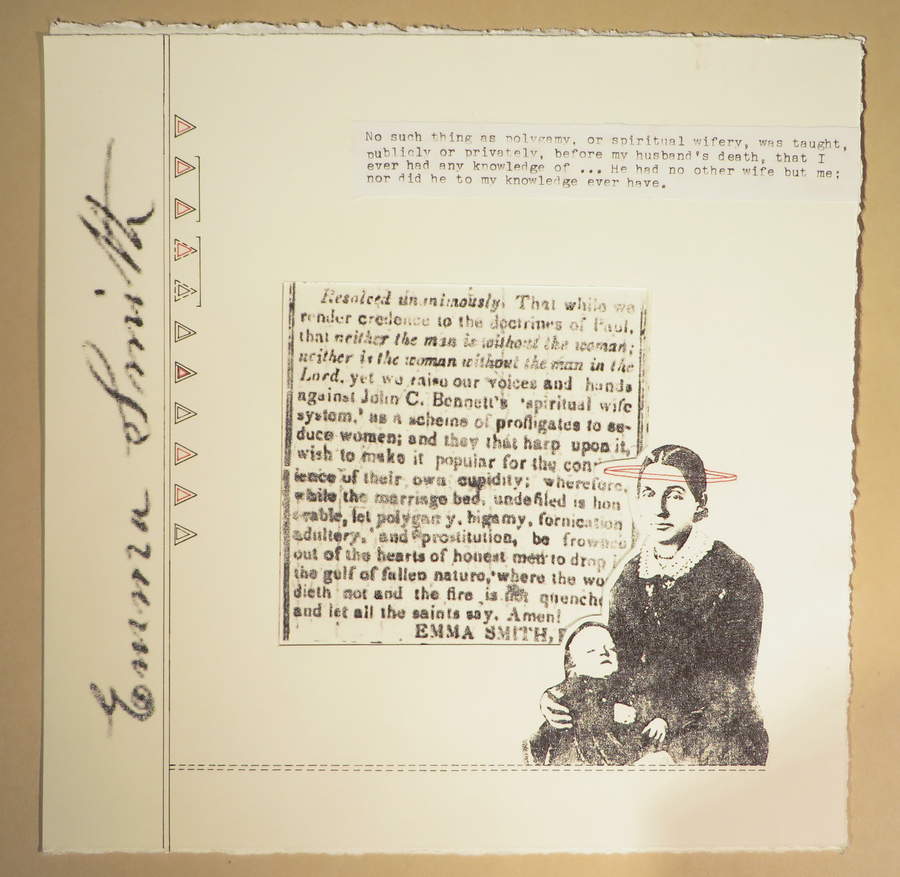

Katie West Payne’s series ends, rather than begins, with the image of Emma (Fig. 9). Symbols represent her life story, a photo transfer allows Emma to look straight at the viewer, and a typewritten slip of paper reveals words that she spoke shortly before her death, emphatically and categorically denying the prophet’s polygamy. But through a window Payne invites viewers to see a different version of Emma’s thoughts. A second, rear panel shows an excerpt from an 1844 resolution authored by the women’s Relief Society, of which Emma was then president. In it, Mormon women declare they will “raise their voices and hands” against all licentious abuses of women, including polygamy.2 By ending the series with Emma and juxtaposing her conflicting statements about polygamy, Payne’s implication is that Emma was both victim and perpetrator, and should be recognized as such.

- 1Leslie’s Art Blog, June 22, 2014, http://leslieopeterson.blogspot.com.

- 2The original document, titled “The Voice of Innocence from Nauvoo,” also bears Emma’s signature. This document is available online from the LDS Church History Library.

Angela Ellsworth’s work on polygamy shows Emma as the wife who demonstrated agency, whether it was through pushing a rival down the stairs or untying herself from that which bound her. For Ellsworth, Emma serves as the paragon of freedom, even as her later work also questions the extent to which polygamous marriage should be viewed as limiting. Because she has worked on this theme for nearly three decades, it is not surprising that Ellsworth has also moved into explorations of Mormon polygamy that go beyond the experiences of Smith’s family.

The visual art that focuses on Emma, perhaps more than any other, ignites discussion. It illuminates contested understandings of Mormon history and challenges us to see the present in light of the past. Philosopher Jacques Rancière, who has theorized the role of art in facilitating a public voice for those who have been marginalized—as Mormon women have been—writes: “Politics revolves around what is seen and what can be said about it, around who has the ability to see and the talent to speak, around the properties of spaces and the possibilities of time.”1 Rancière suggests that a given society’s artists create political interventions when they use imagery to rupture a hegemonic discourse, allowing us to conceptualize things for which we may not have previously had words. Art, in other words, is a starting point for social change, including the reevaluation of religion.2 Certainly, the issue to which all of these artists speak is the place of women in the contemporary Mormon Church, and their work is birthed from the tension created by forbidden discussion of it. If the polygamous past is to find a more comfortable and useful place in the chain of memory that is Mormon history, Emma Smith is the starting point for its reexamination and rearticulation. Peterson, Payne, and Ellsworth are doing this and more, by claiming the right to explore polygamy’s history and the right to show the full spectrum of Joseph Smith’s many wives. They provide contemporary examples of the power of art to affect and transform religious memory.

The author expresses thanks to Leslie O. Peterson, Katie West Payne, and Angela Ellsworth for their contributions to this project, and to LDS Church History Library archivist Jeff Thompson for his assistance.

Notes

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2021.2

1. Marie W. Dallam, "Art, Religious Memory, and Mormon Polygamy," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), 10.22332/mav.ess.2021.2.

Dallam, Marie W. "Art, Religious Memory, and Mormon Polygamy." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 5, no. 1 (2021), 10.22332/mav.ess.2021.2.