Ananda Cohen Suarez is Assistant Professor of History of Art at Cornell University, with a specialization in the art of colonial Latin America. She is author of Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes (University of Texas Press, 2016) as well as editor and principal author of Pintura colonial cusqueña: el esplendor del arte en los andes coloniales (Haynanka Ediciones, 2015). She has published articles on colonial Andean art and issues of cross-cultural exchange in the journals Colonial Latin American Review, The Americas, and Allpanchis.

Mural painting was a longstanding artistic practice in the Andean region of South America, stretching back to at least the third millennium BCE. Numerous coastal cultures of Peru, including the Cupisnique, Moche, and Chimú civilizations, produced stunning polychrome murals that decorated both the interiors and exteriors of religious temples and residences. Their iconography was diverse, including mythological scenes, representations of deities, and sacrificial rituals. Fewer mural remains are found at highland sites due to preservation issues, but traces of mural decoration can be found at the pre-Columbian sites of Raqchi and Quispiguanca, among others. Mural paintings frequently possessed iconographic and stylistic resemblances to portable media such as ceramics, textiles, and metalwork. These large-scale public works of art broadcast religious ideologies, mythologies, and cultural values to their constituents, serving as an important conduit for the transmission of knowledge and belief systems.

With the Spanish invasion and colonization of Peru in the 1530s, the visual arts played an integral role in the religious indoctrination of indigenous and Afro-descendant communities to Catholicism. Mural painting in particular became a favored medium in early evangelization efforts because of its relatively low cost and shorter execution time in comparison to multimedia pieces such as retablos (altarpieces) and polychrome sculptures. But most importantly, murals also remained crucial to the conversion process because indigenous congregations would have already been familiar with the medium and the power it commanded due to the long-standing presence of muralism in the Andes throughout the pre-Columbian era. European prints and émigré artists from Spain and Italy brought European iconography and techniques to Andean soil. Peru’s famed émigré artists Bernardo Bitti and Mateo Pérez de Alesio also brought buon fresco and fresco secco techniques that they acquired in their native Italy; Pérez de Alesio in particular had completed a mural of The Dispute Over the Body of Moses (circa 1574) in the Sistine chapel prior to his arrival in South America.1 The circulation of Italian models and mural techniques in the colonial Andes resulted in a number of early mural programs that resemble European prototypes produced an ocean away, such as the cupola murals in the Capilla Villegas from the early seventeenth century (Figs. 1 and 2). Murals also adorned the interiors of casonas (mansions), where colonial officials and elite families would have lived, with mythological scenes and ornamental imagery executed in black and white, such as this example at the Casa de Antonio Zea in the city of Cuzco (Fig. 3).

By the mid-seventeenth century, mural painting had begun to take on a life of its own. Mestizo and indigenous artists came to dominate the profession as Spanish and creole masters were drawn to more prestigious commissions in metropolitan centers. In the rural Andes muralism remained an artistic medium of choice well into the nineteenth century. Archival documentation from church inventories and account books suggests that mural painting was a thankless job; artists were paid disproportionately less than their counterparts working in canvas and panel painting. Nevertheless, murals appear to have acquired a special cachet in rural indigenous villages known as reducciones or pueblos de indios. While the majority of the images in this collection feature murals from churches located in the Cuzco region of Peru (largely in the Quispicanchi and Canas y Canchis provinces to the south of the city), it should be noted that mural painting was practiced throughout Andean South America, with vibrant traditions emerging across Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia, and northern Chile.

A comprehensive study of the peregrinations of itinerant mural artists in the forging of a cohesive Andean mural aesthetic remains to be done. The striking stylistic and thematic similarities across far flung mural programs by the eighteenth century suggest a complex network of artists who traversed interregional commercial circuits and shared techniques, ideas, and source imagery with one another. It is my hope that this research contributes to continued efforts to trace the development of a colonial mural tradition in Andean South America that considers both its European inheritance as well as its rootedness in local aesthetic practices and evocations of sacredness. Further field and archival work will provide us with a clearer picture of the richness and complexity of this art form as well as its special resonance among indigenous communities across the Andes.

This Collection is intended to function as a digital supplement to my recent book, Heaven, Hell, and Everything in Between: Murals of the Colonial Andes, published by the University of Texas Press and available here. As any image-based scholar knows, few book publishers have the funds or capacity to publish every single image that the author desires. Fortunately, the rise of online venues for scholarly publication has facilitated the creation of new hybrid print-digital projects. This image collection includes alternate views and additional details of murals featured in the book as well as entire mural programs that I was unable to include due to space constraints. The images are grouped according to themes that help to enrich some of the material addressed in different chapters of the book.

1. Buon fresco, or “true fresco,” involves the application of pigments to wet plaster, which means that the entire section that the artist chooses to work on must be completed in one sitting. Buon fresco is often considered a more challenging technique because it is more difficult to make corrections once the plaster has dried. Fresco secco, or “dry fresco,” refers to the application of pigments to dry plaster. This was the most commonly utilized technique in colonial Latin America, with some modifications based on availability of local materials.

Worlds of Ornament

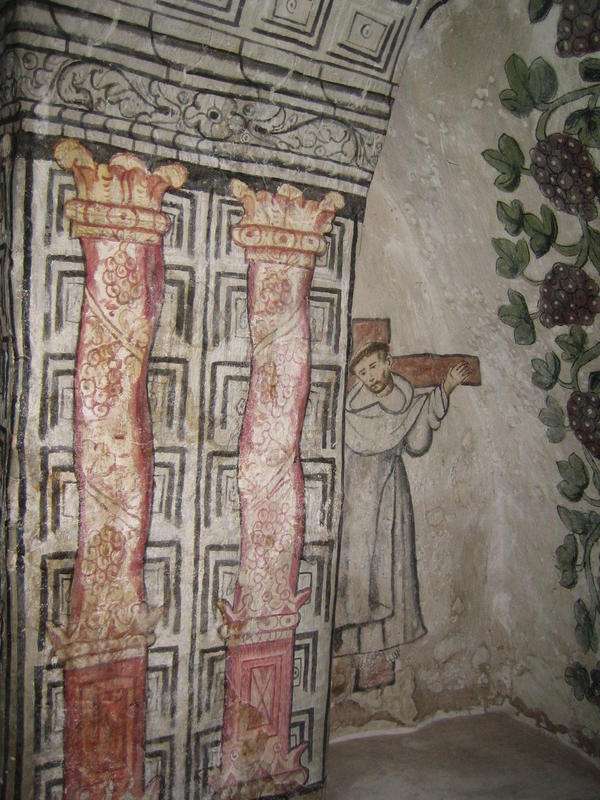

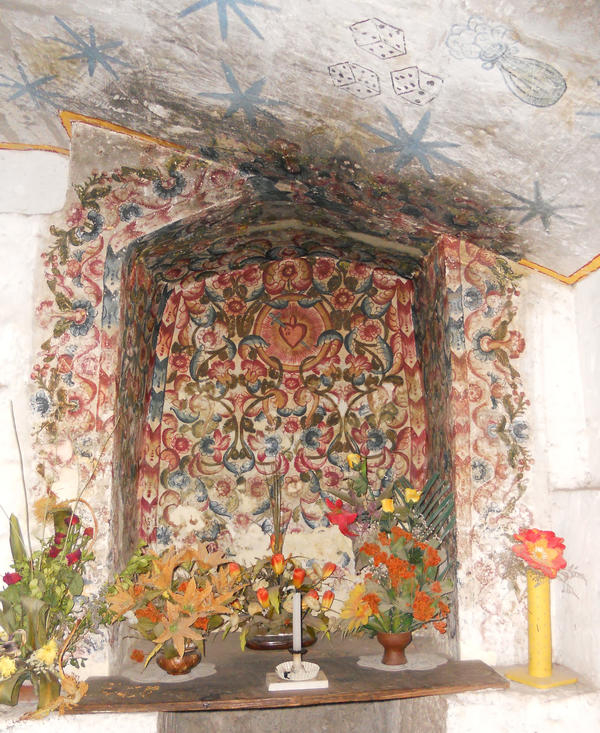

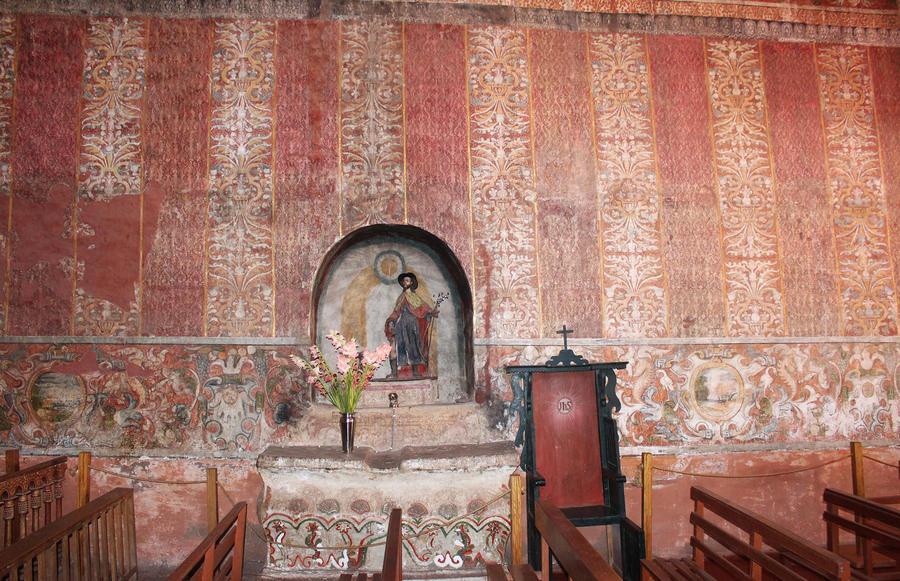

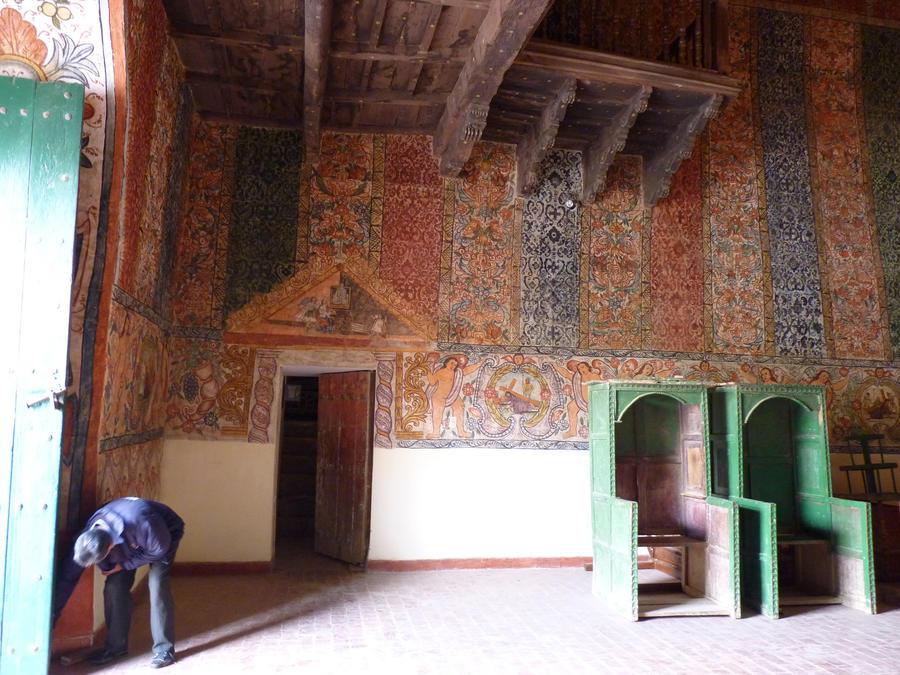

Murals depicting complex allegories, scenes from the life of Christ and Mary, and images of angels, saints, and local devotions tend to attract the most attention in scholarship and popular media alike. However, the majority of extant murals from the colonial period are actually non-figural and decorative in nature. Mural painting served as a quick and inexpensive means to add grandeur to humble spaces, with the ability to imitate precious materials such as fine silks and damasks, precious stones, carved wood, and ceramic tiles. In addition to imitating various materials and textures, ornamental murals often consisted of exuberant floral motifs that give the viewer the impression of being surrounded by a garden paradise, which holds resonance in both Christian and Andean belief systems. The images in this section provide a snapshot of the diverse worlds of ornament that can be found in churches across the southern Andes. Friezes with undulating vines and fantastical creatures, or paintings simulating columns, pilasters, and coffering were likely informed by European prints that would have arrived in the Andes en masse. But we must also consider the creative license that artists exercised in the production of ornamental motifs, which were subject to far less ecclesiastical scrutiny than doctrinal imagery. These murals cue us into the diversity of ornamental designs across the southern Andes and their role in imbuing sacred spaces with a sense of intimacy and sumptuousness.

Fig. 5 Painted archway at the Church of Pitumarca (Canchis Province) with Solomonic columns, strapwork, and decorative emblems. The archway frames another mural with similar adornments that imitates a baroque retablo (altarpiece) with the central niche housing a statue of the Virgin. Photo by Raúl Montero Quispe.

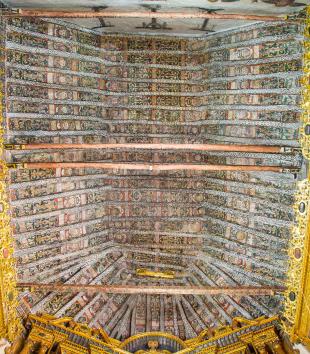

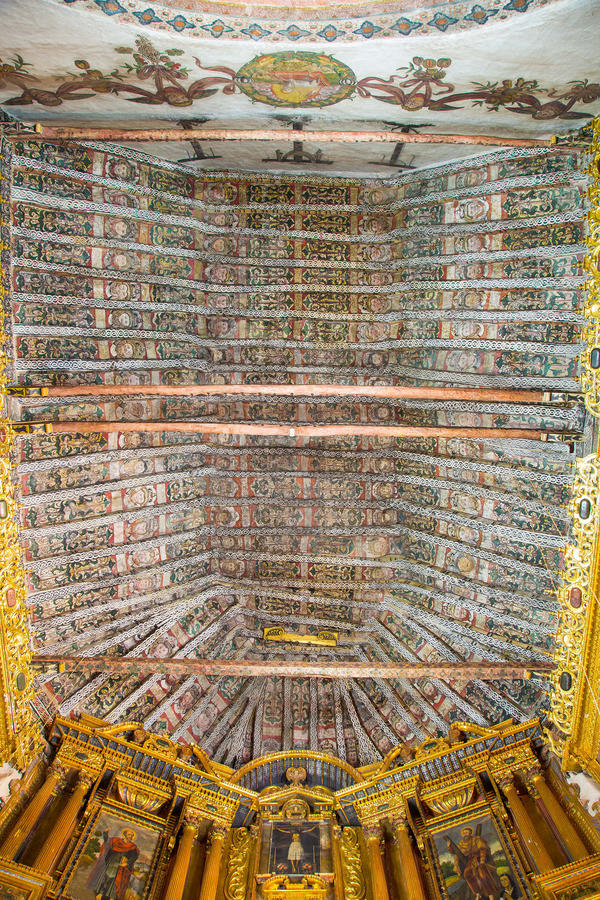

Clothing the Body of the Church: Textile Murals

One of the chapters of the book focuses on a special genre of mural painting known as the mural textil, or “textile mural.” Textile murals were deployed to imitate the appearance of rich tapestries, laces, damasks, and silks hanging from the walls of churches. These textile designs closely correspond with sixteenth- and seventeenth-century liturgical cloths from Spain and Italy that would have been produced for the export market. The phenomenon of the “textile mural” has many points of origin that lend themselves to a multiplicity of visual genealogies. In the pre-Columbian Andes, the Moche (ca. 100 BCE-700 CE), Chimú (ca. 1100-1470), and Inca (1438-1532) civilizations all boast extant archaeological remains of temples and palaces decorated with intricate textile designs. In Italy, to name an iconic example, the Sala dei Pappagalli in the Palazzo Davanzati in Florence boasts fourteenth-century paintings with repeating diamond and parrot designs to imitate the appearance of sumptuous curtains hanging from the walls. Textile frescoes decorated the interiors of private residences across the Italian peninsula to imitate expensive tapestries that would have only been accessible to the wealthiest families. In Spain, the Real Alcázar and the Alhambra boast a kaleidoscopic array of painted stucco geometric patterns that reflect Nasrid textile designs. Each of these sites—the pre-Columbian Andes, Italy, and Spain—possesses their own version of a textile mural modeled off of actual cloths whose designs would have been readily recognizable to contemporaries. While textile murals began to wane in importance in Spain and Italy by the sixteenth century, the genre migrated to South America, which already had its own textile mural traditions, and remained one of the most ubiquitous forms of mural decoration well into the nineteenth century. Textile murals can be found in churches throughout highland Ecuador, southern Peru, western Bolivia, and northern Chile, decorated with strikingly similar color palettes and motifs.

Visual Connections

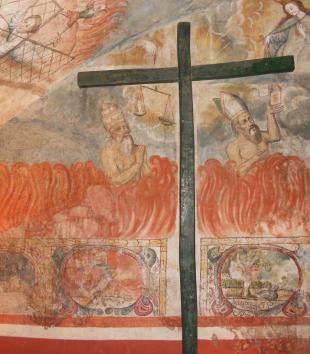

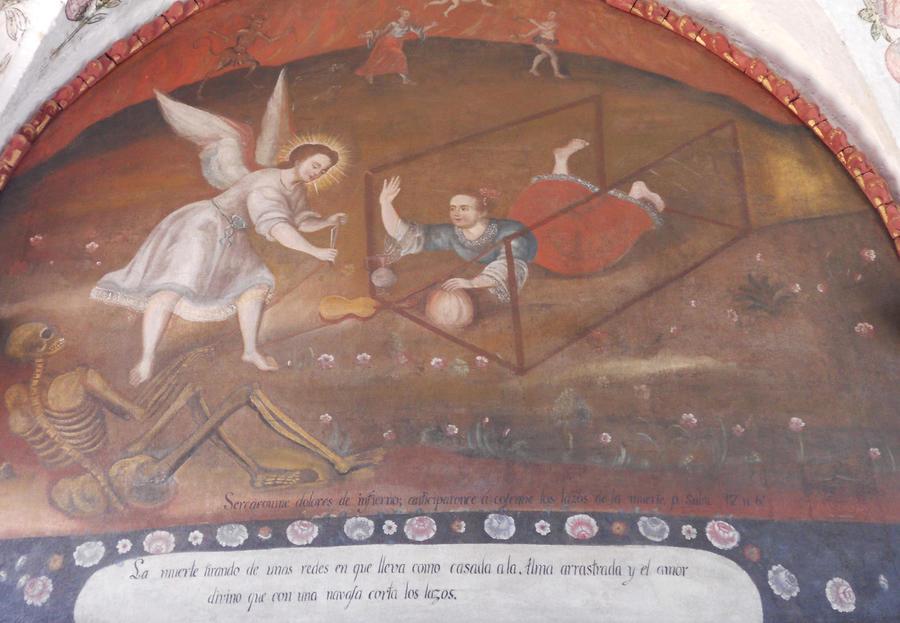

Over the course of several years of visiting and photographing churches across Peru and northern Chile, I was struck by the commonalities in styles, motifs, and iconography found in far-flung murals. This, in part, was facilitated through the dissemination of European prints; the same print could inform compositions in different churches located hundreds of miles apart. Such similarities can also be attributed to the prevalence of certain common themes in eighteenth-century religious painting in the southern Andes, including allegories of death and vivid depictions Purgatory, Hell, and the Last Judgment. Late colonial murals also bear similarities in color scheme and technique; by the eighteenth century, red, green, and earth tones tended to predominate in mural compositions, with a sparse use of blue. The fidelity to naturalistic figures and three-point perspective found in earlier murals began to give way to what some scholars refer to as a “popular” aesthetic characterized by thickly outlined figures, sparse shading, and a shallow compositional space.2

Fig. 23 Detail, textile murals with earlier phase of mural decoration revealed by restorers. The shift in design reflects changing tastes and a growing interest in textile murals by the late 17th century. Even the painting of the Virgin features a red curtain encased by a trompe l’oeil frame made to look as if it were wrapped in fine cloth. Church of Oropesa, Quispicanchi Province. Photo by Raúl Montero Quispe.

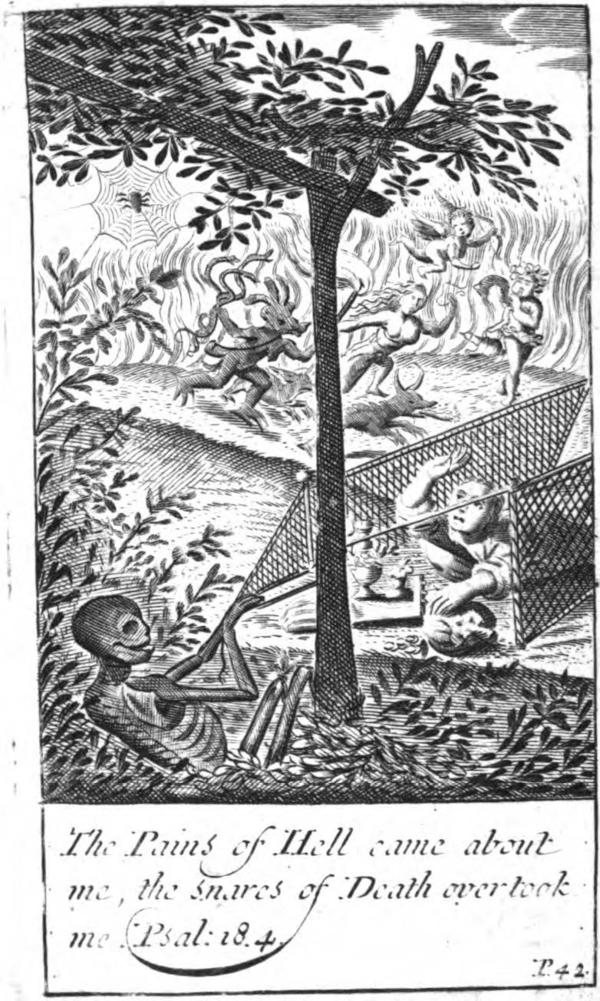

Fig. 25 Mural painting from the Celda Salamanca of the Convento de la Merced (Cuzco), 18th century. Much of the iconography, and particularly the image above with Death housing a human soul in its ribs, derives from one of the emblems included in Diego Suárez de Figueroa’s El camino del cielo, published in Madrid in 1738.

Fig. 27 La trampa del alma (The Trap of the Soul), 18th century, Celda Salamanca, Convento de la Merced (Cuzco). Photo by author. This scene also comes from Suárez de Figueroa’s El camino del cielo, depicting Death tugging on strings in order to trap an individual in a snare who is surrounded by worldly pleasures, including a lute and a pitcher. An angel frantically cuts at the string to prevent the snare from closing.

Fig. 29 Scene of indigenous man praying next to a painted retablo, late 17th century. Church of Oropesa, Quispicanchi Province. Photo by author. By the seventeenth century, imagery of indigenous Andeans praying became relatively standardized iconography. Men were typically rendered in profile to draw emphasis on their praying hands and distinctive hairstyle of balcarrotas (sidelocks).

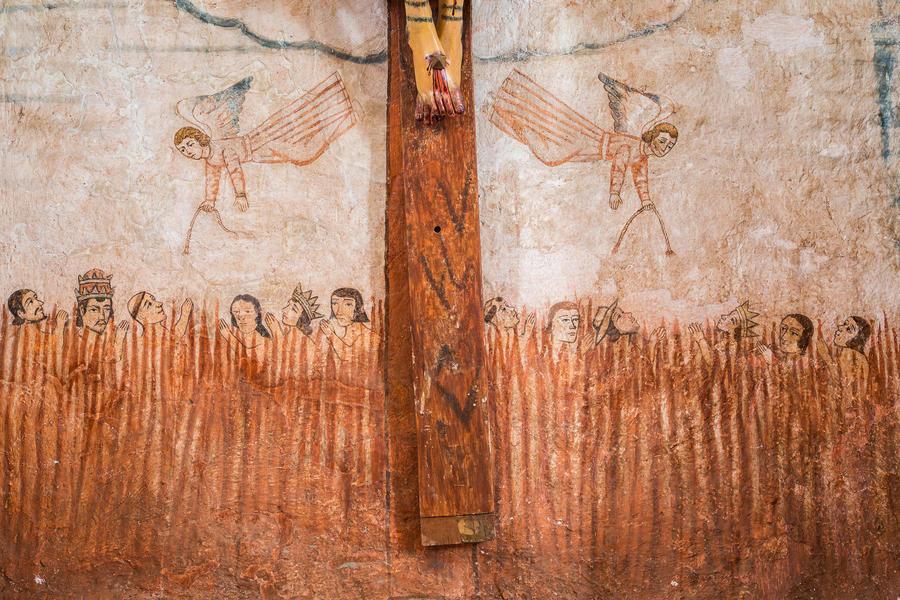

Fig. 31 Painted niche with crucifix, late 18th or early 19th century. Church of Sangarará, Acomayo Province. Photo by Raúl Montero Quispe. This niche incorporates delicate textile designs along the arch and beautifully integrates the crucifix within a painted background with Christ’s body set against a heavenly backdrop and the souls of Purgatory below.

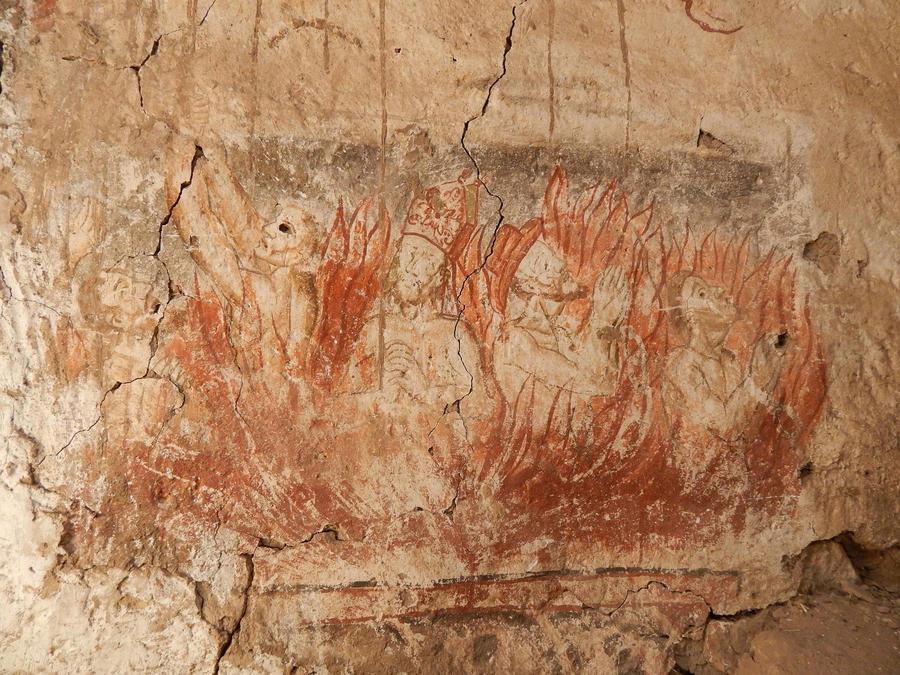

Fig. 34 Detail from Last Judgment by Tadeo Escalante, 1802. Church of Huaro, Quispicanchi Province. Photo by author. In this representation we see men undergoing purification from the flames of Purgatory. As we see often in this type of iconography, some of them men are shown wearing Bishop’s mitres and Papal crowns.

Fig. 38 Last Judgment, 18th century, Church of Zurite, Anta Province. Photo by Raúl Montero Quispe. Representations of the Last Judgment abounded in churches across the southern Andes, in both mural form and in canvas paintings. A number of similarities can be found in murals of the subject in churches across Peru, Bolivia, and Chile, indicating the use of shared European print sources. For instance, this painting bears striking similarity to an 18th-century mural of the Last Judgment at the Church of Parinacota (Chile).

See here for the mural of the Last Judgment at the Church of Parinacota (Chile).

2. For further discussion of the “popular” style that took hold of mural painting in the eighteenth century, see José de Mesa and Teresa Gisbert, Historia de la pintura cuzqueña, vol. 1 (Lima: Fundación Banco Wiese, 1982), 247–255; and Pablo Macera, Trincheras y fronteras del arte popular peruano. Ensayos de Pablo Macera, ed. Miguel Pinto (Lima: Fondo Editorial del Congreso del Perú, 2009).

Additional Views

Murals are notoriously difficult to photograph. Lighting conditions in colonial churches are not ideal for taking publication-quality photos, necessitating the use of artificial lights and flash, which don’t provide a realistic sense of the actual experience of viewing the murals in person. Moreover, with restrictions on the number of illustrations that can be included in a given book, certain mural programs inevitably need to be cropped to show details and others left out altogether. Cropped and edited photographs give a distorted perception of the spatial environments that murals inhabit, and the angle of a photograph can often exacerbate that distortion. The images included here provide some alternate and perhaps unexpected views of the murals included in the book, with the hope of engendering a more nuanced view of these multidimensional, dynamic works of art.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.coll.2016.1

1. Ananda Cohen Suarez, “Painting Beyond the Frame: Religious Murals of Colonial Peru,” Collection, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016), doi:10.22332/con.coll.2016.1

Cohen Suarez, Ananda. “Painting Beyond the Frame: Religious Murals of Colonial Peru.” Collection. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2016), doi:10.22332/con.coll.2016.1