An eruv enhances the Sabbath by facilitating carrying. Jewish law does not normally allow the carrying of objects in public spaces or between private and public spaces on the Sabbath, a prohibition based upon the biblical imperative to “do no work” on that day. This rule can make some simple activities complex. A visit to a synagogue, for example, could involve leaving one’s door unlocked or wearing the key as a decoration. To push a stroller, or a wheelchair, is proscribed. Children may not carry their toys outside to play. If, however, the inhabitants of private dwellings constructed around a common shared courtyard form a partnership allowing them to regard themselves as living together in one home, then during the Sabbath they may carry throughout the courtyard as if in their own homes. Both the proscription and its amelioration are Talmudic.

The eruv boundary marks the borders of these imagined courtyards. It is a work of architecture and urban planning whose program is the neighborhood, and whose materials are the appropriated accumulations of urban life. It is also a work of art whose simple line surrounds and defines the complexity of urban space while it defines the complex human community that inhabits its space.

Part One: Eruv Chazerot

Like many Jewish practices, the eruv makes symbolic use of food: The word “eruv,” which means “mixture” or “partnership,” refers in rabbinic parlance not to boundaries but to a deposit of bread or other food that was and is still used to designate the partnership formed to enhance the observance of the Sabbath. The provision of common food as a symbolic shared meal gave expression to social relationships already encouraged by the design of the shared courtyard: for twenty-four hours a week a deposit of bread, an eruv chazerot (courtyard eruv) conceptually turns one of the homes into a pantry and a courtyard of separate homes into a single courtyard home. The Mishnah Torah, compiled in the twelfth century by Moses Maimonides, stressed the educational value for children of seeing the stash of bread in their courtyard. In some places, a matzo (unleavened bread) is affixed to the wall of the synagogue to signify the eruv. At present, the word “eruv” usually signifies the boundaries of the territory covered by the eruv, while the food has devolved into one or more boxes of matzot, replaced once a year, that now often languish unseen on a high shelf in an unnoticed office, and is sometimes accidentally discarded. Because the 2011 Eruv Chazerot was accidentally discarded, the rabbi supplied the 2012 Eruv Chazerot with a sign. The following year, the “2” in “2012 was crossed out, and replaced with a “3.” The matzo was also replaced with another brand.

Part Two: The Borders

Most discussions of the eruv concern its borders. Wherever Jews live in unwalled cities or neighborhoods rather than courtyards, an area must be symbolically transformed into a courtyard before it can serve as an eruv. The eruv is architecture’s minimum. The transformation often involves little more than the reinterpretation of an existing structure as a “gate,” or “doorway.” Sometimes a simple addition can effect a redefinition: a board that extends between two balconies in adjoining courtyards and can be used as an entrance, or ladders that make adjoining areas mutually accessible to one another. A conception of the minimum construction needed to establish an eruv determines when boundaries are, so to speak, overstepped. Maimonides puzzled over how high a window need be before a ladder is necessary to turn it into an entrance. In modern cities, the construction of an eruv requires an investigation of urban systems whose meticulousness rivals many an architectural project. In order to attain a complete and unbroken courtyard, natural boundaries like a shoreline or a slight depression in the earth, and artificial boundaries like fences, overpasses, and utility wires must all be redefined as interconnecting “gates.” Planners must take into account plazas, patterns of traffic and pedestrian movement, as well as the routes of major roads and much more.

Part Three: The Material of an Eruv

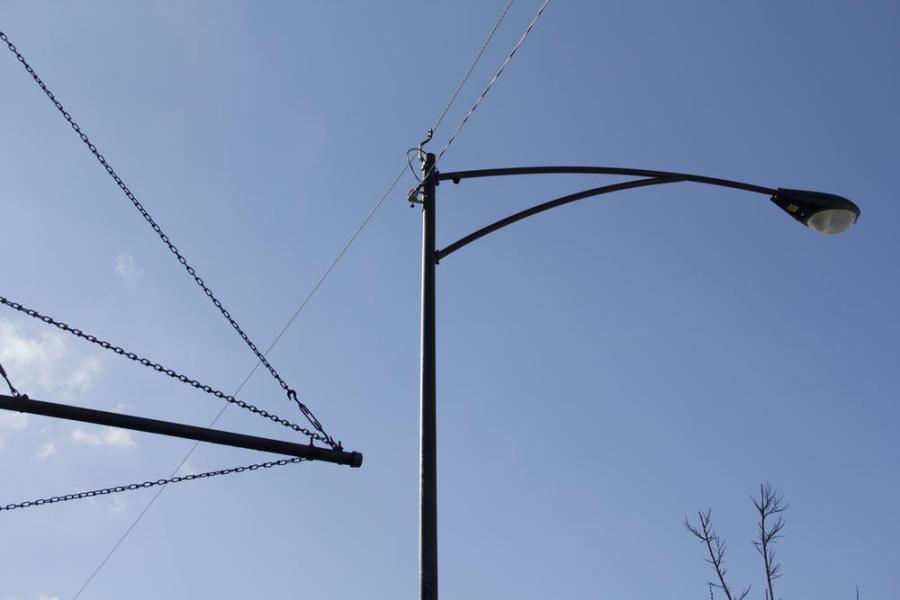

Certainly the eruv is no work of high art. It is closer to bricolage. While the professional engineer uses specialized tools for every project, the bricoleur attacks problems that arise with whatever he has at hand, supplementing what he finds on the street with parts acquired at the hardware store to create the semblance of a post-and-lintel construction. The basic characteristic of a post (lechi) is that it must be directly under (but need not support) a lintel (koreh elyon). If an electric wire were to extend from the top of a pole, it could act as a koreh. More commonly, however, wires extend from the side of poles, or there are none and fishing line (monofilament) affixed above a pole serves as the koreh. It is also possible to attach to the pole directly below the wire or filament a lechi composed of a rubber cable protector, indistinguishable from those used by the electric company. A rubber tip made for the bottom of a chair or a cane may be placed at the top end of the cable protector below the wire, acting as a capital to help identify a wire as part of the eruv. When monofilament is used, a piece of tape or cloth often labels it as a koreh. Only in the absence of utility poles, must eruv builders must independent lechis.

The eruv’s small vocabulary serves primarily as camouflage keeping the eruv from intruding into the urban setting. Even users of the eruv cannot be expected to see it, but need maps to avoid straying accidentally outside. “Stay on the south side of Henry,” advises a helpful note about the New Haven Eruv, “and circle south around both poles on the southwest corner of this intersection before heading north on the east side of Winchester.” Yet every week the eruv must be checked, and any loose fishing line or broken lechi fixed. Hence comes the necessity to maintain a careful balance between camouflaging the eruv, yet keeping the eruv components visible enough to check.

On metal poles, the Yale Eruv uses a strut held on by strapping clamps to act as a lechi. State Street, New Haven, 2010.

In Manhattan, Eruv wires are often tied to rigging hardware eye screws mounted on the top of street signs. Manhattan, 2012.

A cable cover on a utility pole capped by a rubber cap meant for the bottom of a chair leg or cane, directly below a utility wire indicating a symbolic gate made of, respectively a post (lechi), and a lintel (koreh). The cap acting as a capital, is important visually, but not structurally. New Haven, 2010.

A bit of tape on an eruv line helps the eruv checker to see the line. New Haven, 2012.

Part Four: Living with an Eruv: Israel and Palestine

The reason that Eruv fittings need camouflage in Diasporic communities is that the Eruv’s balance between visibility and invisibility is a barometer of the relations within the community. The significance of contact with others is built into the rules and regulations that guide eruv practice. It is necessary to rent permission from the secular authorities to carry on Shabbat. Currently, permission to carry costs the eruv in New Haven a dollar per year, paid to the chief of police; three centuries ago, the same privilege cost the Jews of Altona twelve marks, a considerable sum at the time.

A modern eruv must obtain the consent of utility companies, and often of non-Jewish neighbors who allow the eruv to use their property. In 2006, a Jewish group in Philadelphia held a ceremony for the completion of its eruv in the courtyard of a seminary in order to thank the priests for permitting the fixing of the last line to their fence. Such ceremonies suggest that because it shares its space with others, knowingly or unknowingly, in Diasporic communities this almost invisible boundary can be a powerful symbol of tolerance and multiculturalism.

Yet the building of an eruv can touch off bitter controversies. Non-Jews may fear that Jews are getting special privileges and may find visible eruv structures unsightly. Jews, too, may fight with one another over whether to establish an eruv or how to set it up. Lawsuits lasting years have been fought over Eruvin in several communities in recent decades.

It follows that in Israel, eruvin are public, and permitted everywhere in the country. Attractive curving red Eruv ribbons, tucked unobtrusively near the pole in a North American eruv, curl and uncurl over the middle of streets in Jerusalem, attached to distinctive eruv poles. Nevertheless, vandalism of eruvin by secular Jews is not unknown, and a neighborhood can get tangled in competing, overlapping eruvin belonging to Orthodox Jews of differing ideologies and origins. In the settlements in the occupied territories, eruvin poles and lines that string plastic bottles and cans instead of ribbons make their way almost menacingly through the barren landscape. They link settlements to one another along “firing zones” declared by occupation authorities and across lands confiscated from Palestinian farmers.

© Margaret Olin

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.coll.2015.2

1. Margaret Olin, “Introduction to the Eruv,” Collection, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015), doi: 10.22332/con.coll.2015.2

Olin, Margaret. “Introduction to the Eruv.” Collection. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2015). doi: 10.22332/con.coll.2015.2