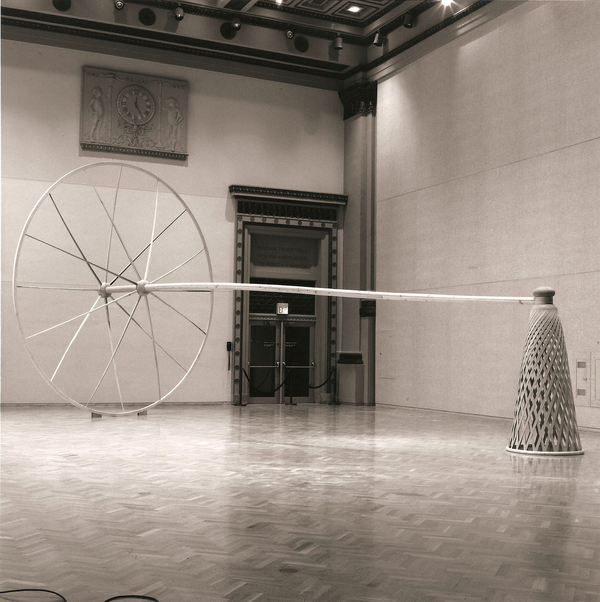

There is very little at first glance in Martin Puryear’s Desire, 1981, that suggests either religion or the sacred. The sculpture—an awkward, oversized wooden wheel joined to an inverted basket—is constructed from vernacular materials (pine, red cedar, poplar and Sitka spruce) rather than rare or exotic woods. The wheel stands twice the height of its viewers and the basket reaches up eight feet towards the ceiling. Each possesses a fantastical quality that places it in an oversized, surreal world of familiar objects rendered uncanny.

But that is our first clue: the uncanny quality of Desire. Puryear alludes to the realm of everyday objects even as he estranges us from it by exaggerating sizes, simplifying forms, and rendering his shapes conspicuously non-functional. The world of handmade objects and manual labor turns strange in this work, and in this way, the ordinary becomes—here is list of options, choose one—estranged, uncanny, defamiliarized.

Given the sculpture’s title, it is hard to discuss the piece without becoming entangled in double-entendres. In thinking of desire, are we discussing wood or sexuality? Is the work’s tactility a reference to the traditions of sculpture or the attractiveness of the body? Is “desire” a term of relation between human subjects or a larger and more abstracted description of the dialectic between wheel and basket? Before answering, we need to bear in mind not just the two quasi-independent objects at either end of Puryear’s piece, but the long wooden tether that unites them. In what way does that tether function as the key to the object’s power? Perhaps this is not a sculpture about wheels and baskets but about distance: the separation that keeps two objects in perpetual relation to each other and in a state of recurrent desire.

And this is where religion enters the picture. That dialectic suggests a yearning from the peripheries for a center always experienced at a distance. The English language is filled with idioms that describe this type of situation: we revolve around someone or something; we run around in circles. Or, alternatively, we are kept at arm’s length, or our feelings are held at bay. What counts in all the above is the gap, the longing, which seems unresolvable: the twoness that can never be one.

Are we speaking suddenly of human-divine relations in a language that echoes the fundaments of neo-orthodoxy?1 Has Puryear transposed the distance between a transcendent and always other Source and its forever circling dependent, into the sculptural tensions of dissimilar objects held together only by longing and perhaps even love? Or should we point ourselves in the opposite direction—away from love—and ask about sin? Has Puryear translated a more Tillichian notion of “sin as separation” into his study of desire? Desire, from this vantage, might be defined as the affective substructure underpinning all separation. It is “sin” by another name.

This theological turn in our reading of Desire stems from two things: a pathos and agony inherent in the piece itself and, in more historical terms, Puryear’s relation to Martin Luther King, Jr, and the early years of the Civil Rights movement. Puryear grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, experiencing segregated Washington, DC as an African American. He graduated from Catholic University in the spring of 1963 and was in Washington the following November for the March on Washington and King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. His commitment to African American history is quiet but powerful. It runs just below the surface of his quasi-abstract objects: his basket forms have been linked to African traditions of basket-weaving (Puryear spent two years with the Peace Corps in Sierra Leone); several of his works from the 1980s, in their upward sweeping forms and rhetoric of transcendence, resonate with the language of the Civil Rights movement; his Ladder for Booker T. Washington, 1996, honors the late nineteenth-century emissary between black culture and white America; and his recent works like Night Watch, 2011, and The Load, 2012, with their swamp-like forms and tropes of surveillance, allude back to nineteenth-century slave experience.

Martin Luther King, Jr. wrote his dissertation on the theologians Paul Tillich and Henry Niemand. Both thinkers tied political activism to religious belief and salvation history. Tillich, in turn, was a central influence upon Jewish theologian Abraham J. Heschel, who marched arm in arm with King at Selma, commenting afterwards, “When I marched at Selma, my legs were praying.”

The point is not to convert Puryear’s abstract sculpture into either a veiled allegory of the Civil Rights movement, or an illustration of existential theology. The goal instead is to hear in Desire the echoes with—the subtle affinities between—civil rights discourse and twentieth-century religious commitment, from the role of the black church in spanning the gap between local resistance and community mobilization, to the emphasis on broken and unfilled national promises in the oratory of Martin Luther King, Jr. What links each of the above is the effort to overcome distances, to reimagine the gap that separates what is from what should be. As soon as we see in Desire a meditation on yearning, an exploration of breaches and of striving towards unfulfilled promises, we begin to understand the complicated ways that Puryear’s art revolves, like that wheel, around questions of justice and salvation. Desire affirms both the pleasures and the pains of history understood dialectically: the need to march towards goals forever at a distance. It is about sin as separation. And Selma.

Why, then, a basket-like form at the center? Why not a form more clearly “transcendent” in shape? Because that basket, with its inscrutable inner space (a recurrent motif in Puryear’s oeuvre) alludes not only to vanquished origins (Africa) and to recovered traditions (handcrafts and woodwork), but to the process of perception itself. Puryear’s basket highlights through its permeable surface both what is visible and what is hidden: how exterior forms hide inner life. But isn’t that the way we talk—or fail to talk—about race itself: as a topic both visible and hidden, a subject with a public face and a veiled interior? Scholar Robert Stepto describes African American literature as a tradition written from “behind the veil.” African American life has been filled with voices that hide—as a matter of survival—what they cannot afford to reveal. So too with Puryear’s basket. It reserves the right to an interior life that remains inaccessible to prying eyes. That basket at the center of Desire embodies in its elegant form four hundred years of African American experience.

And it proclaims, along with the wheel-like shape circling it, the endless dialectic that brings love and justice, sin and separation, image and history, together.

Notes

Notes

1. For a classic overview text on modern Christian thinking and theologies, including neo-orthodoxy and the Tillichian version of existentialism referred to in this short essay, see James C. Livingston, Modern Christian Thought: From the Enlightenment to Vatican II (New York: Macmillan, 1971).

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/con.ess.2014.5

1. Bryan Wolf, "Martin Puryear, Desire," Essay, in Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014), doi:10.22332/con.ess.2014.5

Wolf, Bryan. "Martin Puryear, Desire." Essay. In Conversations: An Online Journal of the Center for the Study of Material and Visual Cultures of Religion (2014). doi:10.22332/con.ess.2014.5