Edward J. Blum is Professor of History at San Diego State University.

Joint publication with Journal of Southern Religion available here.

When Harriet Beecher Stowe endeavored to explain a major life transition for the titular character of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, she marshalled material metaphors. Uncle Tom had been sold from his kind owner in Kentucky and sent “down river” to a new master, Simon Legree. She foreshadowed the horror Tom would experience by comparing him to “a chair or table, which once decorated the superb saloon, comes, at last, battered and defaced, to the bar room of some filthy tavern, or some low haunt of vulgar debauchery.” Her simile had limits, and Stowe used them to pivot to one of her novel’s main points. Although property, Tom and other slaves were people. Unlike the table or chair, Tom and others had emotions: “the table and chair cannot feel, and the man can.”1

When Stowe put Tom into action, she also emphasized how “the man” could attempt to control aspects of his life through the material. When Tom met his new master, Legree tried to establish and exercise his dominance by seizing Tom’s possessions. Legree ransacked Tom’s trunk of clothing and compelled Tom to remove his “best broadcloth suit” and “shining boots.” In the robbing process of disrobing, Tom had the wherewithal “to transfer his cherished Bible to his pocket.”2

Legree failed to find this bible, but he grabbed Tom’s “Methodist hymn-book.”3 This became the occasion for Legree to verbalize the degree of despotism he desired: a totality of tyranny. He observed and then asked, “Humph! pious, to be sure. . . . You belong to the church, eh?” When Tom replied firmly “Yes, Mas’r,” Legree shot back, “Well, I’ll soon have that out of you. . . . I’m your church now! You understand,—you’ve got to be as I say.” Tom uttered no audible reply. Internally, in the realm of his thoughts and feelings, he answered “No!” He drew to memory words that a young white girl, Eva, had often read to him from her bible, “Fear not! for I have redeemed thee. I have called thee by name. Thou art MINE!”4

In this fictional account, Tom stood as an object among objects, a possession among possessions. Stowe layered into this short scene contests over content. By possessing Tom legally, Legree claimed ownership of Tom’s material artifacts. The hymnbook served as the entrée to assert authority above and beyond that of God. Tom protested covertly. In his interiority, he felt the claim of God upon him. He was owned, not by the wicked master Legree, but by the loving master God. Externally, Tom rebelled by pocketing “his” bible. Although Tom never hid as a fugitive, he concealed his tangible bible as an assertion of his faith, his personhood, and ultimately his relationship to forces beyond the material world.

This dramatic scene hinged upon several particularities of bibles in the middle of the nineteenth century. Readers learned earlier that Tom’s bible was a “testament.” As such, it contained only the books of what most Christians called the New Testament. As Stowe made clear, Tom’s “reading had been confined entirely to the New Testament.”5 As a testament, it constituted about one-third of the size of a complete “Bible,” the kind Eva had shared with Tom. That bible contained the passage Tom drew to mind. The forty-third chapter of Isaiah, a book within the portion of the Bible Christians often call the Old Testament, read “I have called thee by name.” With regard to size, Eva’s bible would never have fit into Tom’s pocket; concealment would have been a catastrophe. The smallness of his particular testament made his secretive possession possible.

Stowe made robust use of bibles in this moment and throughout Uncle Tom’s Cabin. By making his testament a pocketed stowaway, Tom materially and physically rejected the totality of Legree’s ownership and mastery. When Stowe had Tom draw to mind passages from Eva’s bible—or had those passages invade his mind—Stowe gave voice to his interiority. He had thoughts, feelings, and beliefs. Legree could claim as much physical and material domination as he liked, but he could not control Tom’s feelings or faith.

This article examines biblical materiality in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, its various illustrated editions, and its theatrical and cinematic afterlives. It argues that the various bibles addressed profound issues of the co-construction of race and religion from the middle of the nineteenth century to the first decades of the twentieth.6 First, in the realm of slavery and race, Stowe’s deployments of bibles and artistic representations of them in illustrated editions offered a conservative abolitionism that emphasized the potential for peace among former slaves and masters. She presented bibles as mending forces, rather than liberating ones. Her presentation of bibles emphasized the moral and emotional humanity of African Americans, but not their legal, political, or economic rights. This differentiated her from radical white abolitionists, such as William Lloyd Garrison, who used biblical concepts to damn southern whites for benefiting from slavery, or violent abolitionists, such as John Brown, who came to believe their bibles legitimized the militant overthrow of enslavement. While radical abolitionists focused upon equality, Stowe used bibles to promote harmony. In this way, Uncle Tom’s Cabin offered bibles with the power to unite, rather than divide, and to emphasize that Christianity could bond black and white southerners in harmonious quiescence.7

Second, this essay will show that bibles in the afterlives of Uncle Tom’s Cabin continued to offer moderation when it came to issues of race and racial interactions. In the decades after emancipation and amid tensions over interracial sexuality, theatrical and cinematic portrayals of Uncle Tom’s Cabin used bibles in ways that created distance from the inequalities of slavery and emphasized control over relations between black men and white women. Tracing the presences, absences, and transformations of bibles as theatrical props, this essay shows how Uncle Tom’s Cabin reflected and played a role in the ways northern whites wished to feel positive fulfillment for the end of slavery and also the sacred sanction of Jim and Jane Crow. All in all, the bibles of the many versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin offered solace to white northerners who longed for racial peace without racial justice.

By using the various bibles of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as entrées into nineteenth century and early-twentieth century American culture, this essay builds upon and endeavors to connect scholarly literature on bibles as material objects, northern white abolitionism, and the co-constructions of race and religion. When book historian Paul C. Gutjahr published his path breaking An American Bible: A History of the Good Book in the United States, 1777–1880 in 1999, he observed that “scholars have paid stunningly little attention to ‘the book’ when considering ‘the Book.’” This was an accurate assessment when Gutjahr first claimed it, but the twenty years since have seen bibles analyzed in a variety of ways with Gutjahr leading the way. He demonstrated strikingly how material production, commodification, production, diversification, and distribution networks transformed the place of the Bible from “the Book” to “a book among books.”8

While some scholars continue to approach “the Bible” solely as a set of dematerialized ideas, many others locate profound meanings in the particular material forms and uses of bibles. Matthew Brown and David Cressy, for instance, demonstrated how Puritans in colonial America physically used bibles in a variety of ways. Bibles were thrown to express disgust. They were attached to poles and raised high to lead rebellions.9 Looking to the nineteenth century, art historian David Morgan identified how physical bibles and the art within them addressed issues of national identity, millennial beliefs in Christ’s return, and media transformations of the era.10 Most recently, Seth Perry detailed how bibles served as sites where editors, writers, and readers subtly and not-so-subtly crafted and undermined notions of religious authority. This was especially important for Americans living in the vacuum of religious authority rendered by church disestablishment.11 All told, scholarship on biblical materiality shows that “the Bible” is best understood with attention to “bibles.” The ideas of the scriptures had meaning in relationship to and with the material forms of the pages, typescript, annotations, images, packaging, binding, size, and weight. This approach makes it possible to examine key points and themes Harriet Beecher Stowe made in Uncle Tom’s Cabin by looking to the particular forms of the bibles within her novel.

The bibles Stowe and visual illustrators created for Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the theatrical renderings following, offer windows into northern white antislavery perspectives of slavery, race, southern society, and race relations after emancipation. Curtis Evans detailed in The Burden of Black Religion how constructions of “black religion” created the notion that it served as the “chief bearer of meaning for the nature and place of blacks in America.” The overemphasis on black religiosity became a means to define a totality of black life and experience. It also worked to discredit the intellectual capacity of African Americans. By emphasizing emotion and spirituality in “black religion,” whites throughout the nineteenth century presented blacks as a counterweight to the “materialistic” culture of the white middle class. Evans fittingly charges Stowe as an important accessory in the formation of this racialist stereotype.12

The bibles of Uncle Tom’s Cabin did this and more. They worked to render African Americans as innately religious and associated them with children. These bibles also characterized the Bible—and the Christianity it represented—as a calming influence in the South. Amid enslavement, bibles did not inspire rebellion or violence. They created shared communities of familial intimacy that allowed whites and blacks to live together peacefully. In the decades after slavery, the bibles of Uncle Tom’s Cabin presented the injustices of slavery as relics of the past and racial segregation, especially the distancing of black men and white women, as Christian concepts.

- 1Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, vol. 2 (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852), 168.

- 2Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:169–70.

- 3As Seth Perry and other scholars have, I follow the distinction between “the Bible” as an overall idea and “bibles” as specific material objects. See “Note on Capitalization” in Seth Perry, Bible Culture and Authority in the Early United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018), xv.

- 4Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:170.

- 5Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, vol. 1 (Boston: John P. Jewett, 1852), 191.

- 6For an introduction to the co-constructions of race and religion in the United States and many current “states of the field,” see Kathryn Gin Lum and Paul Harvey, eds., The Oxford Handbook of Religion and Race in American History (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018).

- 7For a succinct discussion of the various forms of white abolitionism, see Richard S. Newman, Abolitionism: A Very Short Introduction (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018); for more on the role of Christianity in various forms of white abolitionism, see Bertram Wyatt-Brown, Lewis Tappan and the Evangelical War Against Slavery (New York: Atheneum, 1969).

- 8Paul C. Gutjahr, An American Bible: A History of the Good Book in the United States, 1777–1880 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1999), 3.

- 9David Cressy, “Books as Totems in Seventeenth-Century England and New England,” The Journal of Library History 21, no. 1 (Winter, 1986): 92–106; Matthew P. Brown, Pilgrim and the Bee: Reading Rituals and Book Culture in Early New England (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015).

- 10David Morgan, Protestants and Pictures: Religion, Visual Culture, and the Age of American Mass Production (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 43–122.

- 11Seth Perry, Bible Culture and Authority in the Early United States (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018). For other discussions of biblical materiality, see Andrew T. Coates, “The Senses of Fundamentalism: Visual and Material Culture in the Rise of American Conservative Protestantism,” (PhD diss., Duke University, 2016), especially 115–28; Alexandra Kaloyanides, “Baptizing Buddhists: The Nineteenth-Century American Missionary Encounter with Burmese Buddhism,” (PhD diss., Yale University, 2015), especially 15–79; Benjamin Lindquist, “Mutable Materiality: Illustrations in Kenneth Taylor’s Children’s Bibles,” Material Religion 10, no. 3 (September 2014): 316–44.

- 12Curtis J. Evans, The Burden of Black Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 4–6.

Books within Books

Harriet Beecher was born in 1811, the daughter of Reverend Lyman Beecher. Five years later after his daughter’s birth, he helped found the American Bible Society (ABS). The two—Harriet and the ABS—grew up together. As they matured, they became primary players in the expanding world of books and book culture in the first half of the nineteenth century. Harriet was surrounded by readers and writers. Her father published many of his sermons, and her sister Catharine published A Treatise on Domestic Economy in 1841. In only a few years, it went through more than ten editions. In 1836, Harriet married Calvin Stowe, who spent most of his career working as a professor of Biblical literature.1

Years before she published Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe made a mark in the publishing world. Throughout the late 1830s and 1840s, she published an abundance of magazine articles, pamphlets, and books. She also helped her husband Calvin publish a fictional biography of Jesus, writing the introduction and a short piece on Jesus as an infant. Uncle Tom’s Cabin vaulted Stowe to the center of American letters. Her work began as serialized chapters in The National Era, an antislavery newspaper, in 1851. In bookform, it sold more than 300,000 copies in one year.2 By the end of 1852, those seeking to purchase the novel had options. They could buy it in two volumes, either with a few illustrations or with many, and in distinct bindings.3

Uncle Tom’s Cabin benefited from the material world of books that the ABS and other publishers developed in the first half of the nineteenth century. The ABS altered the terrain of American book publishing, particularly with regard to bible production. As Gutjahr and several other scholars have detailed, the ABS and evangelical reform organizations like it used centralized production, printing with steam power, and in house binding to lower costs and increase efficiency. They also utilized distribution networks by sending their wares over improved transportation systems of roads, canals, and then railroads. All of this allowed them to flood the United States with print religious materials.4

When, in 1829, the ABS planned to place a bible in every American household within two years, they focused upon inexpensive, small, and sturdy bibles. Over the next twenty years, they produced and distributed millions of bibles. Prices dropped to six cents for testaments—what Christians called the New Testament—and less than fifty cents for bibles containing the so-called Old and New Testaments. To compete, other publishers produced diversified forms and packaging options to enter the bible market. Harper and Brothers, for instance, produced a massive Illuminated Bible in the 1840s with hundreds of small and large images. Increasingly, publishers manufactured “mega-bible” editions that were much larger and heavier than the testaments. The ABS followed suit, adding to its repertoire more luxury bibles aimed at middle-class audiences and above. Commodity diversification became a hallmark of nineteenth century bible publishing.5

Harriet Beecher Stowe penned Uncle Tom’s Cabin in this environment and created distinct bibles within it to convey numerous meanings. The physicality and particularities of the bibles served important functions. In fact, they only work within the novel because of their materiality and the assumption that readers would recognize their differences. Readers encounter three distinct material bibles in the course of the book: Uncle Tom’s testament; Miss Ophelia’s annotated family bible; and Evangeline St. Clare’s complete bible. The materiality of each facilitated many of the points Stowe desired to make.6

Readers first met Uncle Tom’s testament on August 7, 1851, two months after the serialized story had begun in The National Era. “Tom sat by, with his Testament open on his knee, and his head leaning upon his hand—but neither spoke.” Awake long before others, Tom felt sad for he knew the day would bring family separation. His white Kentucky owners, the Shelbys, had experienced a financial disruption and determined reluctantly to sell several of their slaves. Tom mourned that morning. His testament matched his emotional state: speechless.7

Throughout the rest of the novel, Tom maintained his possession of the testament. It traveled with him from sale to sale, plantation to plantation. Sometimes he read it on his knee, other times he placed it on cotton-bales to read. When he first met Legree, Tom’s testament was the one physical item he was able to maintain. Time and again, Stowe stressed Tom’s ownership: it was “his” book. His ability to keep it, carry it, and conceal it hinged upon its smallness and lightness.

Stowe differentiated Tom’s testament from other bibles by what it lacked. His bible “had no annotations” and no “helps in margins from learned commentators.”8 In this way, his testament stood in contrast to the second bible Stowe included, a “Scott’s Family Bible” full of annotations and commentaries by Scottish pastor Thomas Scott. Readers encountered this bible when Stowe shifted the attention from Tom in New Orleans to the New England household of Ophelia St. Clare. Stowe introduced readers to her through material objects: Miss. Ophelia’s home had clean rooms “where everything is once and forever rigidly in place,” there is an “old clock in the corner” and in the family room, “the staid, respectable old book-case, with its glass doors.” Within it sat a history book, John Milton’s Paradise Lost, John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and “Scott’s Family Bible.” There are other books, too, but these received specific names.9

- 1Joan D. Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe: A Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 1–88.

- 2Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe, 76–88, 188.

- 3Hedrick, Harriet Beecher Stowe, 223; Claire Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1852–2002 (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2007), 91–112.

- 4Gutjahr, An American Bible, 10–81. David Paul Nord, Faith in Reading: Religious Publishing and the Birth of Mass Media in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004). For a history of the ABS see John Fea, The Bible Cause: A History of the American Bible Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

- 5Gutjahr, An American Bible, 10–81. Sonia Hazard, “Bibles, American Style,” Common-Place: The Journal of Early American Life 17, no. 2.5 (Winter 2017), hdl.handle.net/10079/6656e31e-6f97-49a9-9e6f-a2f19dee8aa3.

- 6For more on Stowe’s use of biblical passages and concepts, see James H. Smylie, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin Revisited: The Bible, the Romantic Imagination, and the Sympathies of Christ,” American Presbyterians 73, no. 3 (Fall 1995): 165–76; “The Bible & the Novel,” Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture, accessed August 22, 2018, hdl.handle.net/10079/ebda27f3-c360-4e72-b99c-600b576246cb.

- 7Harriet Beecher Stowe, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin: Or, Life Among the Lowly,” The National Era 5, no. 32 (August 7, 1851): 1.

- 8Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:210.

- 9Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:226.

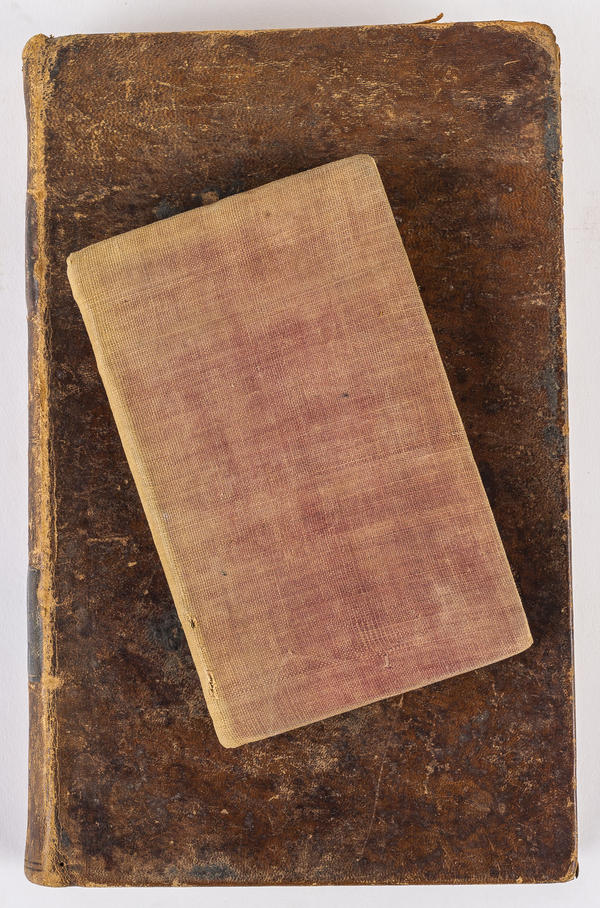

Figs. 1 and 2 Juxtapositions of American Bible Society “testament” with one volume of Thomas Scott Bible. The New Testament of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ (New York: Printed by David Fanshaw for the American Bible Society), 1832.

The Holy Bible: Containing the Old and New Testaments, according to the authorized version: with explanatory notes and practical observations. By Thomas Scott, D.D. Rector of Aston Sandford, Bucks (Boston: Published by Samuel T. Armstrong and Crocker and Brewster), 1823.

While Milton’s and Bunyan’s works were staples of New England home libraries, especially for the children and grandchildren of Puritans, this bible was not just any bible. Stowe provided a specific name and type. Published first in the United States in 1804 by Philadelphia printer William W. Woodward, Scott’s biblical commentary was six hefty volumes. Its full title was The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments, according to the Authorized Version, with Explanatory Notes, Practical Observations, and Copious Marginal References, by Thomas Scott, Rector of Aston Sandford, Bucks.1

For marketing purposes, booksellers referred to it as Scott’s Family Bible and printed that name on its binding. Scott’s annotated bibles were popular among the wealthy and erudite. Thomas Jefferson, for instance, purchased them from publisher William W. Woodward for twenty dollars.2 As a book among books, housed within a family room, Scott’s Family Bible accentuated what Tom lacked. Miss Ophelia and her family had various books to read. Within those books, they had commentaries and annotations. They had a regular place, indoors with seating, to read in peace and quiet.

But neither this bible, nor the other books of her library, inspired Ophelia to compassion or kindness. After she moved south to help her cousin, Augustine St. Clare, manage his household, she treated the slaves, particularly a young girl named Topsy, with stern cruelty. Ophelia desired the household to mirror hers in New England: rigid and organized. She routinely whipped Topsy who exhibited playful disregard for Ophelia’s rules and regulations. Only after the death of her niece Eva did Ophelia begin to treat Topsy with care, going so far as to call her a friend. In Ophelia’s case, her annotated family bible failed to produce action. Stowe seemed to use this particular bible to indict the northern Puritanism which she regarded as stultifying and un-Christian. In The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe hammered this point home, writing that Ophelia represented those who lacked “that spirit of love, which, in the eye of Christ, the most perfect character is as deficient as a wax flower.”3

Unlike Ophelia’s bible with annotations already within it from a learned minister, Tom made his testament a living book with his own markings. As Stowe rendered Tom, he established a relationship with this material object through his performances upon it. Tom provided his own emotional and moral roadmap with ink and a pen. Stowe did not indicate what precisely Tom added, other than to say his testament was “marked through, from one end to the other, with a variety of styles and designations.” After being sold from the Shelbys in Kentucky to the St. Clares in Louisiana, Tom added tear drops to the pages which conveyed his sadness and carried the memories of his Kentucky home and his forced departure. In these ways, Stowe presented Tom in line with nineteenth-century trends of marking, inscribing, and altering physical bibles, the actions Gutjahr identified as ways Americans related to their many bibles.4

By drawing attention to different forms of marking—some with writing utensils, others with tear drops—Stowe characterized Tom as having a multi-material and multisensory engagement with his bible. While writing in the Bible by manipulating a utensil in hand may have demonstrated intellectual engagement with faith, crying into it with tears dropping from eyes signaled an emotional response. Stowe represented the robustness of Tom’s humanity, in particular his emotion and faith, through his interactions with the Bible, a totality of personhood that slavery endeavored to deny him and others held in bondage. At no point, however, did Tom’s bible inspire him to demand freedom or rage against the injustice of the regime.

Evangeline St. Clare, the daughter of Tom’s second owner, possessed the third bible of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. A committed Christian who bound her faith and life intimately with those enslaved on the plantation, Eva shared her bible with Tom. She often read it aloud and he interpreted the meanings of the passage.5

Unlike Tom’s testament, Eva’s bible contained the books of the Old Testament and the New Testament. Stowe makes this point when she emphasizes how the parts of the bible that she enjoyed most “were the Revelations and the Prophecies.” Later, when Tom draws to mind words from the book of Isaiah, he took from “the Prophecies.”6

For her father, Eva’s bible became the material mechanism by which he endeavored to remember her after she died tragically. When Tom found Augustine St. Clare mourning, he was “holding before his eyes her little open Bible.” When in the hands of the adult St. Clare, Stowe described Eva’s bible as “little.” In this way, Eva’s bible stood as a surrogate for Eva herself—Stowe referred to her as “little” time and again and she became popularly known as “Little Eva.”7 Later, as Tom implored St. Clare to put faith in God, he responded, “Tom, I don’t believe, . . . I want to believe this Bible, and I can’t.” “This Bible” was Eva’s, a book that embodied his attachment to Eva’s lifeless little body.8

Along with these bibles as material meaning makers within Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe and her publisher also used subtle typographical adjustments upon biblical passages to add further layers of meaning to the bible in the lives of the characters. When Tom internally rejected Legree’s demand that Tom abandon his faith, he heard “Fear not! for I have redeemed thee. I have called thee by name. Thou art MINE!” While the fictional Tom experienced these words internally, readers observe them through reading. They also view them in a form slightly different from their bibles. Stowe and the publisher made the words visually—and thus materially—distinct. Most obviously, they printed “mine” with all capitalized letters. They also capitalized the first letter of “thou.” Most bibles and biblical commentaries of the time did not capitalize any of these words except for “I.” With the typographical change, the print version accentuated the personhood of Tom—that he was a “Thou” and not just a “thou.” The book also shouted the possessive ownership of God, rather than Legree.9

Stowe and her publisher used another typographical marker, along with page positioning, on a biblical passage to produce meaning when she displayed Tom reading his bible. Stowe described how he labored word-by-word through one of Christ’s teachings in the Gospel of John and used em dashes to highlight this process: “Let—not—your—heart—be—troubled. In—my—Father’s—house—are—many—mansions. I—go—to—prepare—a—place—for—you.” This passage, moreover, stood as its own paragraph and the lengthened dashes drew the eye to this particular paragraph. In a few subtle ways, the book version looked different from the one printed in The National Era. In the magazine, a few of the words lack em dashes. “In my,” “house are,” “I go to,” and “for you” did not have separators. Overall, the alterations and additions emphasized how this particular verse was meaningful to Tom externally and internally.10

This was a particularly astute and meaningful choice for a verse. The passage signaled Stowe’s conservative abolitionism. It emphasized that through faith, Tom would obtain more than the cabin he lost. One day, he would live in a mansion. That mansion, however, would not be on Earth. Just as Stowe, at the end of the novel, prophesied liberty for African Americans as occurring outside of the United States through emigration, this passage positioned fulfillment beyond the realm of the United States. The verse also consisted of words with only one or two syllables. As literary scholar Christopher Hager emphasized in his study of nineteenth-century enslaved African American reading and writing, these men and women often had the most facility with one and two syllable words. This paralleled the learning developments of white children who started with monosyllable words and progressed onto two syllable ones.11

Compared with other typographical choices of the era, those of Uncle Tom’s Cabin seemed to use visual distinctiveness to emphasize Christian faith, rather than worldly liberation, equality, or to mark the horrors of enslavement. According to literary critic Hester Blum, dashes sometimes allowed African American women writers to mark sexual violence. Harriet Jacobs and Elizabeth Keckley, for instance, placed dashes in their writings to note and elide such violations. They signaled violence without giving it words. David Walker’s Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World (1829) offered another contrast to Stowe. Literary scholar Marcy J. Dinius has identified how Walker’s Appeal was a “graphic riot of italics, small and full capitals, exclamation points, and pointing index figures.” In this way, as Dinius argues, Walker gave graphic voice to his outrage, emotion, and call for fundamental change to American society. Stowe’s typographical use of capitalization and dashes for these biblical passages signaled these sentiments to readers, but did not address sexual brutality or human liberty.12

These three bibles, and the meanings Stowe made through and with them, made sense because of the material transformations of bibles in the nineteenth century and how many Americans worked with their bibles. By the 1850s, readers were familiar with the differences among testaments, small bibles, and mega-bibles that contained commentaries. Tom’s testament, small in size and light in weight, allowed it to serve as a piece of property he could maintain, conceal, and have with him throughout his journeys and labors. Eva’s full bible offered them access to all of the biblical texts, but was still small enough for her, a child, to hold, open, and read without a desk. Scott’s Family Bible symbolized the wealth and intellectual life of the grandchildren of New England Puritans.

The bibles conveyed meaning through their particular imagined materiality. Tom’s testament helped establish him as an emotional, spiritual, and physical being who made external choices based upon internal feelings. For Stowe, this distinguished Tom as a person from the slave as a thing. The bibles did not encourage any challenges to slavery or racial injustice beyond those points. Her bibles also established a contrast between the living, active faiths of Tom and Eva and the staid, inflexible faith of Ophelia. These points made the most sense in the broader context of biblical materiality of the age and promoted abolitionism without drastic social, economic, or political transformations.

- 1Thomas Scott, The Holy Bible Containing the Old and New Testaments (Philadelphia: William W. Woodward, 1804).

- 2“Proposal for Scott’s Family Bible,” in John Scott, Life of the Rev. Thomas Scott, D. D. (Boston: Samuel T. Armstrong and Crocker and Brewster, 1822) advertisement after 454; William W. Woodward to Thomas Jefferson, 30 March 1810, Founders Online, accessed August 22, 2018, hdl.handle.net/10079/bb2d4e85-30b1-46ad-88e8-31c49c7ce5eb.

- 3Harriet Beecher Stowe, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1854; repr., New York: Arno Press and the New York Times, 1968), 51.

- 4Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:188–89. Gutjahr, An American Bible, 143–46.

- 5Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:267

- 6Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:62.

- 7Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:211, 258, 267, 312.

- 8Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:121.

- 9Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:170. For comparison, see Isaiah 43:1. The Holy Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments (New York: Stereotyped by A. Chandler, for “The American Bible Society,” 1830), 638. For other examples of the typographical difference, see Isaiah 43:1, William Jenks, ed., The Comprehensive Commentary on the Holy Bible, vol. 4 (Boston: Shattuck and Company, 1835), 426; Beriah B. Hotchkin, Upward from Sin (Philadelphia: Presbyterian Publication Committee, 1869), 106.

- 10Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 1:210.

- 11Christopher Hager, Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013), 51.

- 12Hester Blum, “Douglass’ and Melville’s ‘Alphabets of the Blind,’” in Robert S. Levine and Samuel Otter, Frederick Douglass and Herman Melville: Essays in Relation (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 257–78; Marcy J. Dinius, “‘Look!! Look!!! at This!!!!’: The Radical Typography of David Walker’s Appeal,” PMLA 126, no. 1 (January 2011): 55–72.

Bible Visualizations within the Books

In its published form, Uncle Tom’s Cabin followed the trajectory of bible production: diversification and elaboration. Her novel became in material form a set of distinct novels—each publication different from the others. Just as publishers created larger bibles, added images to them, and subdivided the book into discrete books for distribution, they did the same to Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The most notable differences were in visual imagery within the novels. Near the end of 1852, after Uncle Tom’s Cabin had sold hundreds of thousands of copies in the United States and Britain, a reviewer in Edinburgh explained, “The questions among publishers now is, who can sell the best edition for the money?” This reviewer believed one factor would determine that: the “illustrations.”1

The proliferation of various versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin also multiplied the potential meanings for Stowe’s bibles, as they figured prominently in the visual adaptations of the text. Alongside textual references to and discussions of bibles in the narrative, visual representations of Tom’s testament and Eva’s bible marked the illustrated editions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Just as it mattered in the novel which bible in particular Tom had access to, read, drew to mind, and pocketed, it mattered which particular version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin one read when considering the place and meaning of bibles. Overall, the presentations of bibles visually worked to maintain that “the Bible” could unite white and black southerners socially and religiously. “The Bible” as a totality and a material presence could bring harmony amid the strain and stress of the era.

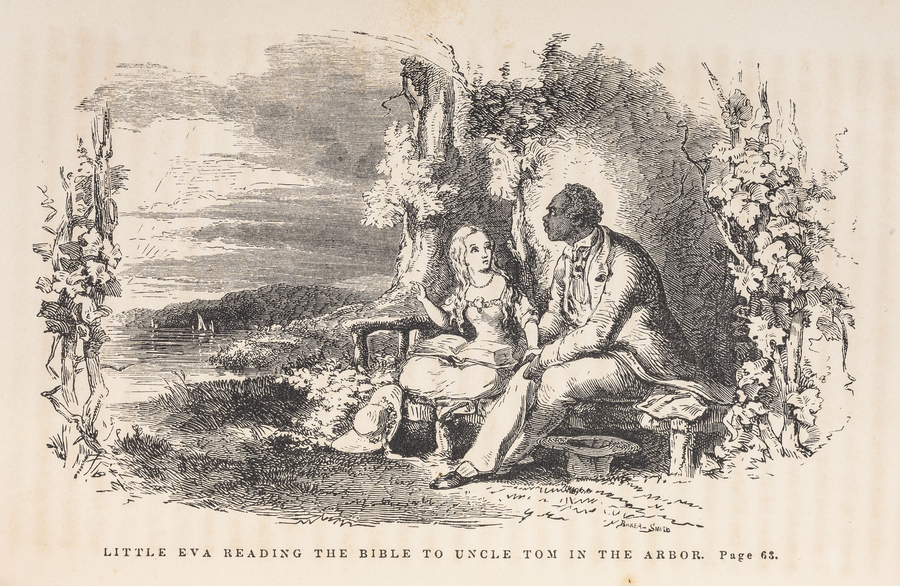

The first book edition, produced in two volumes in 1852, featured six full-page illustrations.2 Hammat Billings, an illustrator who also worked on William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, did not include Tom’s testament in any of these visual representations. Only one of the six pictures featured a bible, captioned “Little Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the Arbor.” It positioned Eva at the center with a large bible resting on her lap. With her extended index finger she directed Tom’s gaze to the distance. We know from the narrative that Eva read from Revelations, “And I saw a sea of glass, mingled with fire.” She gestured to the lake in the ethereal distance and explained that this biblical sea was there. This became the most popular image from the first edition. Publishers used it to advertise the novel and it often constituted the book’s cover. In a far reaching analysis of this image and subsequent artistic adaptations, scholar Jo-Ann Morgan has maintained that the scene created a perception of Eve as teacher and Tom as student. In this way, even the young Eva was a master of Tom.3

- 1William Tait and Christian Isobel Johnstone, eds., review of Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, the History of a Christian Slave, by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Tait’s Edinburgh Magazine 19 (December 1852): 761, quoted in Senchyne, “Bottles of Ink and Reams of Paper,” 153.

- 2For more on the visual culture of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, see Jo-Ann Morgan, Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture (Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2007).

- 3Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin 2:63. For more on the importance of this image, see Morgan, Uncle Tom’s Cabin as Visual Culture, 30–31; Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 22.

Yet, in efforts to emphasize hierarchy, Morgan and other scholars minimize the emphasis on connection. Physical contact was vital within the text of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the illustrations. As literary scholar Aaron Ritzenberg has detailed, “sentimental touch” allowed “characters and readers alike” to “experience profound emotions.” Ritzenberg emphasized that touches signaled the importance of “the human body . . . about the buying, selling, and controlling of the body.” In the case of “Little Eva Reading the Bible,” the book makes the contact of flesh meaningful. The book itself, as a material object, connected Eva, a white girl, with Tom, an African American man.1

Placed within the books, and therefore viewed within their material confines, the sizes and positions of the visual images offered material and sensory experiences for viewer-readers. The publisher had “Little Eva Reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the Arbor” set after a blank page. The image was turned and set broadside. Reader-viewers first had their gaze and reading flow disrupted by the blank page. Then, to view the image properly, they had to physically turn the book ninety degrees. This compelled specific attention to the scene. To see the image, viewer-readers also had to hold it close. For some whites who may have interacted rarely, if ever, with African Americans or slaves in person, they now beheld and held an intimate scene in an intimate way. Viewer-readers mimicked the behavior of Tom and Eva: they held books. Due to the placing and the size of the image, the book drew viewer-readers close to this religious and interracial moment. They too had the opportunity to experience peace and calm amid the troubles of the era.2

- 1Aaron Ritzenberg, The Sentimental Touch: The Language of Feeling in the Age of Managerialism (New York: Fordham University Press, 2013), 1, 16. For another exploration of touch, see Robin Bernstein, “Everyone is Impressed: Slavery as a Tender Embrace from Uncle Tom’s to Uncle Remus’s Cabin,” in Racial Innocence: Performing American Childhood from Slavery to Civil Rights (New York: New York University Press, 2011).

- 2On the importance of smallness or “miniature,” see Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993).

Although Morgan makes the claim that there was no antecedent visual imagery among antislavery activists for “Little Eva reading the Bible to Uncle Tom in the Arbor,” it seemed to adapt an image from the frontispiece of The Star of Freedom, a book of antislavery stories published in the 1840s for children. In The Star of Freedom, the artist depicted two children—one white, one black —reading a bible together. Both children held the book, while the white child draped her right arm across the shoulder of the black child. The image emphasized intimacy through closeness, touch, and the bible. In both Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Star of Freedom, bibles served as visual representations of material objects meant to convey affection and harmony.1

Publishers referred to the second edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin as the “Illustrated Edition.” Packaged in one volume, the publisher capitalized on the growing trend of gift giving at Christmas and distributed it in December 1852.2 It contained more than one hundred large pictures and numerous smaller ones. Each chapter began and ended with a drawing and there were twenty-seven larger ones within various chapters. In this way, it mimicked Harper’s Illuminated Bible, which also combined smaller images with larger ones to punctuate the text. Both texts also used ornamental capital letters for the first word of chapters.3

- 1The Star of Freedom (New York: William S. Dorr, Printer, c. 1840s), title page.

- 2Parfait, The Publishing History of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 81; Penne L. Restad, Christmas in America: A History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), 91-104.

- 3Gutjahr, An American Bible, 70. The Illuminated Bible, Containing the Old and New Testaments (New York: Harper and Brothers, Publishers, 1846). hdl.handle.net/10079/0023bb03-ecb2-4933-bc97-5c84c2e67cc6.

Of the many visual images in the Illustrated Edition, at least seven featured Tom with bibles. A bible braced Tom as he tried to console his fellow slave Lucy; it sat on his lap when he met Eva; it accompanied him as he greeted Augustine St. Clare; it rested by him as he lay dying. In this scene, the book was open, but Tom neither looked at it, nor touched it.1

Although Billings appeared to distinguish Eva’s full bible from Tom’s testament by their size, his testament appears much larger than the inexpensive testaments of the time period. It is difficult to imagine Tom hiding such a large book from Legree’s greedy gaze. For Billings, perhaps the need to draw viewer attention to the book meant enlarging its appearance from that of specific bibles of the period.

When Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin, when Billings illustrated it, and when John Jewett published it, they entered a profound debate between and among antislavery forces and their proslavery opponents. Since at least the 1830s both sides had endeavored to link biblical texts, concepts, and ideas to their cause. As Mark Noll, Molly Oshatz, and other scholars have shown, countless Americans looked to the contents of their bibles to determine if slavery should continue to be part of American law and society. Writers produced works with clear and simple titles such as The Bible Against Slavery and Bible Defence of Slavery. For many Americans of the 1850s, “the Bible” had become a polarizing text, one that disunited the people.2

While debates over particular passages and meanings within the book took place, another struggle ensued over the material presence (or lack thereof) in the American South. When considering the materiality of bibles and their totality as objects, the positions and perspectives of contending parties became more complicated. This was evident in the “Bibles for slaves” campaign and subsequent discussions in the two decades before the publication of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In the 1830s, some abolitionists in the North critiqued the American Bible Society and other similar organizations for failing to reach out to slaves. Critics suggested that if the ABS was serious about its mission, it would distribute books to African Americans in the South. This created an intense debate in the 1840s, as northerners and southerners, whites and blacks, struggled over the rights of slaves to read and possess books. The ABS refused to accept donations earmarked for the production and distribution of bibles for African American slaves. The organization hoped to avoid the slavery controversy.3

The “Bibles for slaves” campaign demonstrated that the ideas of the Bible and the materiality of bibles could factor distinctly, even oppositionally, in antislavery and proslavery debates. Some antislavery activists believed that the sheer presence of material bibles would devastate the institution of slavery. Typifying this sentiment, white abolitionist Joshua Leavitt declared: “the Gospel will burst the bonds of the slave!” Former slave Henry Bibb agreed and worked tirelessly for this cause.4

Frederick Douglass disagreed. Douglass routinely used biblical passages and concepts to denounce slavery. He often presented the ideas of biblical passages and concepts to support liberty and equality. Yet he was opposed to plans for the American Bible Society or other northern Protestants to provide bibles to slaves. In 1848, he excoriated those who “would not lift a finger to give the slave to himself” but would give “the slave the Bible.” He drew attention to material and distributive problems endemic to the campaign. “How do they mean to get the Bible among the slaves? It cannot go itself—it must be carried.” In addition, of what value is a book for those who cannot read? Would these organizations also send “teachers”? To Douglass, while conveying biblical principles of freedom and dignity to slaves would be a boon to the antislavery cause, literal bibles would do nothing. To him it was “a sham, a delusion, and a snare.”5

Stowe and Billings engaged these contexts both ideologically and graphically through their use of bibles in the novel’s presentation. In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, the materiality of bibles, as much as their ideological contents, served to advance Stowe’s particularly conservative antislavery cause. With the bible’s physicality, described textually and observed visually, Stowe and Billings added additional layers of drama to the overall point that slavery as a system propelled noble whites to immoral actions while empowering horrible whites to sinister behavior.

This became apparent in a place where bibles were absent: Simon Legree’s plantation. Before this part of the narrative, bibles abounded. Tom carried his; Eva read hers; and Augustine mourned for his dead daughter by clutching her bible. When Tom worked for Legree, he experienced biblical emptiness literally and figuratively. On one occasion late at night, Tom “drew out his Bible, for he had need of comfort.” “What’s that?” asked a female slave. Tom replied, “A Bible.” The surprised woman remarked, “Good Lord! Han’t seen un since I was in Kentuck.”6

On another evening, Tom once again took “his worn Bible from his pocket” and looked for guidance, or at least solace. Finding none, he sighed and returned it to his pocket. At that point, Tom heard a “course laugh.” Legree was watching him. “Well, old boy,” Legree taunted, “you find your religion don’t work, it seems!” Then, Legree tempted Tom to “heave that ar old pack of trash it in the fire, and join my church!” Tom refused and Legree left. The “atheistic taunts of his cruel master” brought his “dejected soul to its lowest ebb.” For Stowe, the lack of a bible on Legree’s plantation served as a material marker for his unchristian and anti-Christian values. This accentuated his wickedness.7

In these scenes, neither Tom, nor Legree debated particular passages or scriptural stories. They approached the bible in its totality, unlike many proslavery and antislavery writers did who knifed through the text in search of points that would support their position or by contextualizing tales within it to consider past historical settings. Instead, Stowe and Billings used the physical totality of the bible to advocate the position that the absence of bibles facilitated despotism while the presence of bibles could bring harmony to the South. Without saying so explicitly, Stowe and Billings advocated the position that the absence of bibles facilitated despotism while the presence bibles could bring harmony to the South. In these ways, Stowe presented bibles as having redemptive power for blacks and whites.

All in all, the bibles described textually and depicted visually in Uncle Tom’s Cabin conveyed important meanings. Through different bibles in distinct settings, Stowe and Billings played upon the material proliferation of bibles in the nineteenth century and their various meanings. Bibles emphasized Tom’s faith, and his connections to genuine Christianity and to Eva. Further, Eva’s bible functioned as a shared resource that connected the two. In these ways, Stowe presented bibles as powerful material symbols for her conservative antislavery agenda: the making of a gentle South where whites and blacks could read and reason together.

- 1Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly, illustrated ed. (Boston: John P. Jewett and Company, 1853), 171, headpiece for chapter 14, tailpiece for chapter 14, tailpiece for chapter 16, and headpiece for chapter 41.

- 2Mark A. Noll, The Civil War as a Theological Crisis (Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2006); Molly Oshatz, Slavery and Sin: The Fight Against Slavery and the Rise of Liberal Protestantism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012); Theodore Dwight Weld, The Bible Against Slavery (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1838); Josiah Priest, Bible Defence of Slavery, 5th ed. (Glasgow, KY: Published by Rev. W. S. Brown, 1852).

- 3John P. McKivigan, “The Gospel Will Burst the Bonds of the Slave: The Abolitionists Bibles for Slaves Campaign,” Negro History Bulletin 45, no. 3 (July 1982): 62–64, 77.

- 4Quoted in McKivigan, “The Gospel Will Burst the Bonds of the Slave: The Abolitionists Bibles for Slaves Campaign,” 63.

- 5Frederick Douglass, “Bibles for the Slaves,” The Liberator 18, no. 4 (January 28, 1848): 13. See Hager, Word by Word, 11; D. H. Dilbeck, Frederick Douglass: America’s Prophet (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018).

- 6Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:184–85.

- 7Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 2:242.

Theatrical and Cinematic Performances

Throughout the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries in the United States, the Bible was never just a book, and the same was true of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Writers, editors, actors, and directors transformed the story and episodes within it into skits, plays, parodies, lantern shows, and motion pictures. In the decades after the Civil War, theatrical and cinematic versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin proved far more popular than the novel itself. In these iterations and transformations, material bibles took on new meanings. As theatrical props, their changing usages pointed to shifts in American society with respect to issues of race and religion. Amid the overall shift from slavery to segregation, bibles in these performances became vehicles for northern whites to imbue racialization with Christian concepts and to create a sense of distance from slavery. Manipulations of bibles within theatrical and cinematic renditions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin helped to further render blackness as religiously distinct from whiteness and to allow northern whites to congratulate themselves and the American nation for bestowing both faith and freedom to former slaves. In this way, northern whites could feel positive closure with regards to slavery, sanctify racial segregation, and avoid concerns for equality and justice.1

Uncle Tom’s Cabin became a play almost as quickly as it was published in novel form. George L. Aiken created the first stage dramatization in 1858 and it became the basis for most productions of the nineteenth century. For the performances in New York City and throughout the North, white actors in blackface usually played the roles of African Americans.2

These performances trafficked the anti-black racism of minstrelsy shows, and bibles factored in the racializing process. In one scene, Little Eva sat on Tom’s knee. She placed flowers in his buttons and a wreath around his head or neck. “Oh, Tom! you look so funny,” Eva exclaimed. All of that happened in the novel, but Tom’s explanation did not. When Augustine St. Clare entered, Tom accounted for his embellishments, “I begs pardon, mas’r, but the young missis would do it. Look yer, I’m like the ox, mentioned in the good book, dressed for the sacrifice.” This quasi-comical, sentimental moment prefigured how Tom later served, like Christ, as a sacrifice.3

Tom’s words played upon notions of black animality wherein Tom likened himself to a beast. According to scholars Anthony Pinn and Mia Bay, African Americans of the nineteenth century often found themselves confronting laws and attitudes from whites that rendered them as animals. Even after the Civil War and the abolition of slavery by constitutional amendment, African Americans often complained that white Americans failed to recognize their humanity.4 Having Tom explain his visual presence as a sacrificial animal, white audiences could accept notions of black animality without associating themselves with slave drivers or white supermacists. The connection to Jesus through “the good book” facilitated a seemingly non-racist form of comparing blacks to animals.

Another moment featuring bibles was when Legree tried to convince Tom to accept his mastership. Legree implored, “didn’t you never read out of your Bible, ‘Servants, obey your masters?’” Unlike in the text of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, where Legree mentioned the bible in general but failed to verbalize any particular passages, this time he uttered one of the most common biblical passages to defend slavery. In the process, he conceded one form of ownership to justify another. He called Tom’s Bible “your Bible,” thereby acknowledging Tom’s possession of it, but claimed that the book could teach Tom to abide by Legree’s ownership. In short, Tom’s book—meaning Tom’s faith—taught that he should obey Legree. Unlike the Legree of the novel, who had no use for the Bible or bibles, this theatrical iteration knew this biblical passage and used it to attempt to sway Tom. This softened Legree by presenting him as religiously reasonable, while the novel painted him as so irreligious that he denied even the presence of bibles on his plantation.5

Over time, both Uncle Tom and the bibles were aged in dramatic portrayals of the story. Scriptwriters and directors replaced the particular bibles of the novel with family bibles that became meaningful not because of their size or annotations, but because of their weathered appearance. In George F. Rowe’s 1878 dramatic rendering, he established the setting of Uncle Tom’s cabin with candles, a table, stools, chairs, a bookshelf, and “an old Bible on it.”6 This contrasted with George Aiken’s script from 1852 which provided no adjective for age. Aiken simply referred to it as a “Bible.”7

Rowe’s post-Civil War, post-Reconstruction script paid particular attention to this bible and its uses. When Tom handled the bible, the script directed him to do so “with reverence.” When learning that he had been sold, Tom “buried his face in the Bible.” Curiously, the script then dropped any mention of this bible or any other for the rest of the performance. When Tom met Eva or then Legree, the bible bore no mention in the script.8 Using the bible to represent black life alone, Rowe played into the romantic racialism of many nineteenth-century whites that connected and conflated black people with religious faith.

By purposefully using an “old Bible” and physically presenting Tom as older, Rowe drew upon two trends in the United States after the Civil War. One was the rendering of Protestant Christianity as “old” or more specifically as “that old-time religion.” The most famous example of that period came from the new song, “This Old Time Religion.” Popularized in the 1870s by the Jubilee singers, a group of African American vocalists from Fisk University who traveled throughout the North to earn donations for the school, the song declared that “this old time religion . . . is good enough for me.”9

The other aging process surrounded Tom himself. Especially after the Civil War, actors portrayed Uncle Tom as remarkably older than he had been visualized or performed earlier. When Rowe introduced Tom, he had Chloe, his wife, refer to him as “my old man Tom.” After this, she repeatedly called him her “ole man” or “old man.”10 Visually, Tom became older in these performances as well. Dan Bryant, for instance, a white actor who often performed in minstrelsy shows, took the role of Tom in the last decades of the nineteenth century. He weathered his face with the burnt-cork for blackface, and used white hair for his head, eyebrows, mustache and beard.11 This Tom looked dramatically older than the graphic ones in the original novel, and in this way separated him in age from Eva.

- 1For more on this overall process, see David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001).

- 2Sarah Meer, Uncle Tom Mania: Slavery, Ministrelsy and Transatlantic Culture in the 1850s (Athens and London: The University of Georgia Press, 2005), 103–30.

- 3George L. Aiken, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly. A Domestic Drama in Six Acts (New York: Samuel French, 1858), 17.

- 4Anthony B. Pinn, Terror and Triumph: The Nature of Black Religion (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2003); Mia Bay, The White Image in the Black Mind: African-American Ideas about White People, 1830-1925 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 117-149.

- 5George L. Aiken, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly, 47.

- 6George F. Rowe, Uncle Tom's Cabin (For Private Distribution Only: Jarrett and Palmer, 1878), 5. hdl.handle.net/10079/a90ca7b9-a5e5-4dae-936e-53c7d77bfb58, last accessed January 24, 2019.

- 7George L. Aiken, Uncle Tom’s Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly, 32.

- 8Rowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 5, 9.

- 9Gustavus D. Pike, The Jubilee Singers and Their Campaign for Twenty Thousand Dollars (Boston: Lee and Shepard, 1873), 198. For more on the Jubilee Singers, see Andrew Ward, Dark Midnight When I Rise: The Story of the Jubilee Singers Who Introduced the World to the Music of Black America (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2000).

- 10Rowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, 6, 9, 10. For more on aging of Tom, see Jo-Ann Morgan, “Illustrating Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture, hdl.handle.net/10079/4a801192-30ba-4ea4-93a1-138ea08d5210, last accessed January 24, 2019. For more on the importance of the “old” in this time period, see Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008), especially chapter 3. Nathaniel A. Windon, “A Tale of Two Uncles: The Old Age of Uncle Tom and Uncle Remus,” Common-Place: The Journal of Early American Life 17, no. 2 (Winter 2017), hdl.handle.net/10079/444a7a27-fb2f-4cf9-85cc-46511972545a.

- 11“The Tommers,” Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture, hdl.handle.net/10079/f8a5b53a-866e-45d1-b53b-304470d22483, last accessed January 24, 2019. See also Robert Daly as Uncle Tom.

Combined, the oldness of Tom and of the bibles allowed viewers to value religious faith and distance themselves from slavery at the same time. In this way, Tom became an embodied relic of slavery, a bygone era, a memory that would fade in time. His old age served as a temporal marker for slavery—that it existed in the past. The old Tom and the old bible worked together to present the antebellum era as a time of the past, perhaps having little relevance to the life of the present age.1

The aging of Tom, as several scholars have examined, also downplayed the potential for any considerations of romantic or sexual connections between him and Eva.2 This point seemed acute in parodies of the plays. Leveraging the popularity of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, some scriptwriters composed humorous renditions of the novel. In one, a key scene hinged upon audience expectations of a bible and dove into the possibility of interracial sexuality.

A Burlesque on Uncle Tom’s Cabin, first written and performed in 1903, placed Tom and Eva in contemporary Chicago. At one point, Tom entered with a book, “intently reading.” Anyone familiar with Uncle Tom’s Cabin would have been primed to assume it was a bible. Eva inquired about the book and wondered if it had suggestions to “put me wise to the Derby entries for next year.” She sat atop a table, called Tom her “beau,” and smoked a cigarette. Tom kept reading. When pressed, he responded that it was “a dream-book.” She pulled Tom close to her and made a wreath of lettuce, celery, and carrots for his head. “Look in those clouds,” she then remarked, as if they were near the lake in the original novel. Rather than reference Revelation, as Eva had, this woman remarked, “don’t they look like South Chicago smoke?”3

This scene bent and toyed with earlier versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a host of ways. Rather than embellish Tom with flowers, this Eva transformed him into an edible food product.4 Moreover, by placing a dream book within Tom’s hands, the parody de-Christianized him. This Tom concerned himself with his interiority, rather than meaning or identity from an external god. No longer a bible-toting, bible-reading martyr, Tom now stood as an urban fool, tricked by the many trafficked books and superstitions of city life.5 Finally, this Eva was no ideal Christian; she stood as a proto-flapper who participated in interracial romance. The parody titillated audiences with the taboo of interracial sexuality, but made sure to distance it from Christianity.6

In the early twentieth century, Uncle Tom’s Cabin became part of the new medium of the age: motion pictures. Once again, Uncle Tom’s bibles, or their purposeful replacements, spoke to shifts and trends in American society and culture. William Robert Daly directed the first major cinematic version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which was distributed in 1914. Tom was played by Sam Lucas, an African American actor born in 1839 who began his career performing in blackface on riverboats before the Civil War. He was the first African American actor to perform as Uncle Tom and he did so for the first time in the late 1870s.7

Several scenes put bibles to work, and all of them occurred about halfway through the forty-minute film. In one, as Tom and others were being transported down river to New Orleans, he led the group in Christian worship by reading from his bible. Then, after Eva fell into the water, he cast aside his bible and dove in to save her. In the novel, Stowe made no reference to his testament at this point. The cinematic moment with the bible dramatized Tom’s heroism. In another scene, the general events had occurred in the novel, but the particular use of the bible did not. For the famous scene of Eva and Tom reading, the title card placed him as the actor: “Uncle Tom tells Eva of the New Jerusalem.” Then, the bible sat squarely on his lap, not hers. He directed Eva and then at the end of the scene, he walked off with this bible. He maintained possession of it. In the cinematic rendition, Eva’s bible was now Tom’s. When she died, her father did not use it to mourn for her. Later in the film, Tom still possessed what appeared to be this bible.

By emphasizing Tom’s possession of the book and his religious directing of Eva, the cinematic version made Tom the central signifier of religion. The film added another example of the “burden of black religion” whereby religiosity was seen as innately part of African Americans’ personalities and beings.8 Also, in an era where D. W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation (1915) presented African American men as contemptible villains who wished to prey sexually upon white women, the scene from Uncle Tom’s Cabin posed interracialism as plantation nostalgia that assumed and taught that life was better when blacks were slaves and whites were masters. In the cinematic version, Uncle Tom became like Uncle Remus—an older black man who regaled young whites with stories and mythologies.9

More than ten years later, in 1927, another cinematic adaption of the novel hit American theaters. African American actor James B. Lowe starred as Uncle Tom, and this film moved the beginning of the action to 1856 (four years after the novel was published). It carried the events into the Civil War. This film was profoundly bible-less, much like Legree’s plantation. Filmmakers shifted the Christian themes from the visual to the sonic. Just about every moment Tom stood on screen or when other characters discussed him, the orchestral background music resounded with the spiritual “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen.” Materially and visually, Tom lacked a bible. Instead, the sounds of the sorrowful spiritual shaped his aura, and audiences were to know he was sacred by the music.10

One scene set during the Civil War focused on Tom reading to Eva, but it was not a bible. Instead, he held a newspaper. She laid in bed, ill and weak. He sat at a distance. The headline of the newspaper read “Lincoln Proclaims Freedom of Slaves” and recounted the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation of September 1862. Eva rejoiced at the news and said to Tom, “that means you can go home to your wife and babies!” Tom clasped his hands in a prayer of gratitude.

- 1For more on northerners distancing themselves from slavery and the Civil War, see Nina Silber, The Romance of Reunion: Northerners and the South, 1865–1900 (Chapel Hill, NC and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 124–58.

- 2See Morgan, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, chapter 1; Thomas F. Gossett, “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” and American Culture (Dallas, TX: Southern Methodist University Press, 1985), 280.

- 3Harry L. Newton, A Burlesque on Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Chicago: Will Rossiter, 1903), 8–9.

- 4For connections between food and race, see Kyla Wazana Tompkins, Racial Indigestion: Eating Bodies in the 19th Century (New York and London: New York University Press, 2012), 1.

- 5For more on considerations of African American religiosity at the time, see Kathryn Lofton, “The Perpetual Primitive in American Religious Historiography,” in The New Black Gods: Arthur Huff Fauset and the Study of African American Religions, eds. Edward E. Curtis IV and Danielle Brune Sigler (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 171–91.

- 6For more on Christianity and interracial marriage and sex, see Fay Botham, Almighty God Created the Races: Christianity, Interracial Marriage, and American Law (Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2009).

- 7“Uncle Tom’s Cabin” (1914), IMDB, hdl.handle.net/10079/c04ee137-bdfa-4e18-8285-2bf747350e90. The film can be viewed at hdl.handle.net/10079/b14c2e4e-9066-4fa4-a2e0-efb6b32bb3b2.

- 8Curtis J. Evans, The Burden of Black Religion (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008).

- 9Kathleen Diffley, “Representing the Civil War and Reconstruction: From Uncle Tom to Uncle Remus,” in A Companion to American Fiction, 1865–1914, eds. Robert Paul Lamb and G. R. Thompson (Wiley Blackwell: Malden, MA: 2005).

- 10Harry A. Pollard, director, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1927). The film can be viewed at hdl.handle.net/10079/f3955e45-7ad6-44d5-a0b9-f77b4491328c. For more on the role of sound and religious meaning, see Isaac Weiner, Religious Out Loud: Religious Sound, Public Space, and American Pluralism (New York: New York University Press, 2013).

The change reoriented the meaning of the story. The news of the day replaced the “good news” of the bible. Affairs of this world took precedence over those of the next world—both for Eva and for Tom. No longer did bibles bind them in hopes for heaven. Instead, the newspaper bore the most meaningful information. It took the place of a bible, and Abraham Lincoln now stood where god or Jesus once had. By clasping his hands before Lincoln, Tom mimicked statues and images after the Civil War that featured former slaves kneeling before Lincoln or Union soldiers. In all of these ways, the scene created a form of civil religion wherein the nation and its president gave African Americans their longed-for salvation.1

The change in Tom’s interactions with Eva were also telling. Their conversation no longer emphasized heaven or otherworldly salvation. They no longer shared a tangible bible. The sacred scriptures no longer served as a material connector between the two. Instead, they now aspired for his liberty and family reunion. The physical separation of their bodies by her illness, the bed, and his chair kept them close enough to talk, but distant enough to avoid touching. They neither sat side-by-side, nor held hands. They did not share tangibly or materially the newspaper, as they had the bibles in previous renderings. In this way, the scene facilitated the maintenance of race relations within the social structure of segregation. The ultimate goal was separation—that Tom would be with his family, away from Eva. In addition, amid the era of spectacle lynching where whites often falsely claimed they were protecting white womanhood from oversexed black men as an excuse to murder black men, the separation of Tom and Eva’s flesh made it difficult for audiences to fear anything sexual or romantic in their interactions.2

- 1For more on civil religion, see Philip Gorski, American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press). For more on prayers to Lincoln, see Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997).

- 2For more on this social culture, see Grace Elizabeth Hale, Making Whiteness: The Culture of Segregation in the South, 1890–1940 (New York: Vintage Books, 1999).

Conclusion

Introducing the “first large-scale investigation, past and present, of the Bible in daily American life,” Philip Goff, Arthur E. Farnsley II, and Peter J. Thuesen contended, “the Bible has been central to Christian practice throughout American history.” For them, this should lead to new scholarship that investigates “how people have read the Bible for themselves outside worship, how denominational and parachurch publications have influenced interpretation and application, and how clergy and congregations have influenced individual understandings of scripture.”1 My analysis of the multitude of bibles and meanings they symbolized in Uncle Tom’s Cabin suggests that the scope can be broader.

With regard to issues of slavery, race, and religion throughout the nineteenth century, biblical interpretations, applications, and understandings were only part of the picture. The numerous bibles of the many versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin offer layer upon layer of meaning relating to issues of abolitionism, race, religion, and the materiality of media forms. From its initial publication in The National Era to cinematic productions, authors, editors, publishers, directors, and actors used bibles to signal positions on the most crucial issues of American society. Stowe wrote and published her novel in an age of material transformation for books in general and bibles in particular. Publishing houses created different bibles and Stowe used particular bibles for dramatic and symbolic effect. Visual images for new editions featured bibles in distinct ways and added to the drama of the reading and viewing experience. In this pre-Civil War age of slavery and its endemic violence and racial antagonism, Uncle Tom’s bibles envisioned a peaceful South where whites and blacks could sit and talk together.

In dramatic, parodic, and then cinematic renderings of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, bibles served as meaningful theatrical props. The devil was in the details, such as the age of the bible or which biblical verses characters voiced. Aging Uncle Tom and the bibles allowed northern whites to show reverence for religion, attach blackness to religiosity, and feel a sense of distance from the age of slavery. When a newspaper took the place of a bible, northern whites emphasized civil religion rather than Christian religion. A newspaper became scripture, and Abraham Lincoln became God. Freedom from slavery became more important than faith for salvation. A bible no longer linked Tom and Eva. Instead, his familial autonomy through liberty and distance from her became the primary objective. In an age when segregation had replaced slavery as the primary social structure of white-black relations and whites’ concerns over interracial intimacy facilitated the horrors of lynching, Stowe’s vision of the bible as a uniting force had to be omitted and a new scene created. All in all, the bibles of Uncle Tom’s Cabin had so much to say often without saying a word.

- 1Philip Goff, Arthur E. Farnsley II, and Peter J. Thuesen, eds., The Bible in American Life (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), xx.

Notes

Keywords

Imprint

10.22332/mav.ess.2019.2

1. Edward J. Blum, "Uncle Tom’s Bibles: Bibles as Visual and Material Objects from Antebellum Abolitionism to Jim Crow Cinema," Essay, MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 2 Special Issue: Material and Visual Cultures of Religion in the American South (2019), doi:10.22332/mav.ess.2019.2

Blum, Edward J. "Uncle Tom’s Bibles: Bibles as Visual and Material Objects from Antebellum Abolitionism to Jim Crow Cinema." Essay. MAVCOR Journal 3, no. 2 Special Issue: Material and Visual Cultures of Religion in the American South (2019), doi:10.22332/mav.ess.2019.2